"Itis not necessary for me to remind you of the battle that I have been advocating for several years to re-establish the contact between the world of art and the world of technique; to show that no rupture exists between two different but equally essential expressions of human creativity." Thus wrote Giulio Carlo Argan, one of the most important art historians of the twentieth century, to engineer Guido Ucelli, founder of the Museum, close to its inauguration in 1953, in a letter regarding the III ICOM General Conference that would be held that very year in Milan. Argan had followed with interest the stages of the birth of the museum, and fourteen years earlier, between 1938 and 1939, he had been involved, as inspector of the General Directorate of Antiquities and Fine Arts, in the troubled events of the Mostra Leonardesca also organized in Milan and in which Ucelli himself had participated (in the committee of the section on Hydraulics). An exhibition about which so much has been written lately and of which the National Museum of Science and Technology (as it was called when it was founded) is a bit of a son and heir.

Argan’s recommendation, based on the idea of unity of knowledge and knowledge, found in Ucelli a perfect supporter and concrete implementer. To understand the reasons for the importance of art and the presence of numerous art-historical collections in a scientific museum such as the one in Milan, it is necessary precisely to start from the figure and life of its founder, an exponent of the second generation of the Lombard industrial bourgeoisie. Born in Piacenza in 1885, a graduate of the Milan Polytechnic, the young Guido entered as an engineer at Costruzioni Meccaniche Riva, one of the world’s most important turbine manufacturers. Founded by Alberto Riva, one of the first graduates of the Politecnico itself, it had risen to international prominence by winning the contract for the Niagara power plants in 1899. He married in 1914 Carla Tosi, daughter of another prominent engineer and entrepreneur, Franco Tosi, founder of the Legnano engineering company of the same name and prematurely murdered in 1898. Within Riva Guido Ucelli completed a career that led him to become its president. In his home on Via Cappuccio in Milan, an eclectic residence built around the cloister of an old monastery, Ucelli maintained friendly relations with artists such as Arrigo Minerbi, Amos Nattini, and Edgardo Rossaro and architects such as Piero Portaluppi. Sensibility for art, a love of photography and cinema (Ucelli made real silent films with his family and friends, set between Milan and his beach house in Paraggi, on the promontory of Portofino) united his with many families of industrialists and entrepreneurs from Milan and Lombardy of origin or of ’adoption, of his generation and of the previous one, such as the Amman, the Bocconi, the Candiani, the Cantoni, the Crespi, the Jucker, the Ponti and many others, mostly bankers or industrialists, often but not only, textiles.

|

| The Cloisters of the former monastery of San Vittore, home of the Leonardo da Vinci National Museum of Science and Technology |

Collecting in Milan and Lombardy, especially from the post-unification period and up to the years between the two World Wars, was in fact intimately linked to industrial and banking leadership, more so than in other regions of Italy. In search of social affirmation, collecting ennobled this new ruling class, which in Milan was gradually filling increasingly important roles in political positions as well. In search of cultural recognition, these industrialists (especially those born in the 1880s and active as collectors in the period between the two world wars), had very similar tastes, preferring authors from the previous century, belonging to the currents of Romanticism and Realism, Macchiaioli and Divisionists, and if they bought works by artists contemporary to them, of whom they were often also friends, they still preferred art far removed from the revolutions of the avant-garde or even the happier outcomes of the Novecento style. Paradoxically, these modern entrepreneurs who represented the present and the future, often coming out of the two daughter universities of Milanese modernity, namely the Politecnico and the Bocconi, needed a look at the beauty of the past, reassuring and consoling, to complete their lives and their image.

Guido Ucelli also, thanks especially to his contribution in the recovery of the Nemi Ships, one of the most important archaeological enterprises of Fascist Italy, had the opportunity to come into contact with the world of culture at the highest levels by knowing, between the 1930s and 1940s, archaeologists such as Roberto Paribeni or Museum directors such as Giorgio Nicodemi and Fernanda Wittgens, thus beginning to build his idea of an Industrial Museum thanks to tireless lobbying at the cultural and diplomatic levels that continued even after World War II, from which he emerged unscathed thanks in part to his and his wife’s work in defending and protecting their Jewish friends, which he also served with imprisonment.

|

| Arrigo Minerbi, La Vittoria del Piave (Milan, Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci, Ucelli donation) |

|

| Bernardino Luini, Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints Anthony Abbot and Barbara (1521; Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci, on loan from Pinacoteca di Brera) |

The inauguration of the Museum, on February 15, 1953 to coincide with the Leonardo celebrations, thus became at once the culmination of a 20-year project and the starting point for putting into practice a policy of acquisitions that would respond to this idea of the unity of knowledge. Ucelli’s deep network of knowledge in industry and art had their effect, and in the early years of the Museum’s life and until the founder’s death in 1964, we could witness a full and conscious response from the world of art, research and industry, with donations not only of machines and memorabilia from CNR, Falck, Tosi, and the Navy but also of a series of important nuclei of works of art: it was an integrated and not a disjointed process. In a thicket of assets that actually record multiple provenances, it is worth mentioning at least some of the most important nuclei.

As early as 1952, before the Museum was inaugurated, Fernanda Wittgens, granted the Museum an important nucleus of torn frescoes by Lombard masters of the Renaissance that had not found a place in the reorganization of the Pinacoteca di Brera, which reopened in 1950. The event also sealed the closeness between the two institutions under the sign of architect and mutual friend Piero Portaluppi, who signed both reconstruction projects. With the display of these works, Ucelli also pursued the intention of restoring some of its Renaissance allure to the cloisters of the former monastery of San Vittore that housed the museum, also employing himself in the purchase of antique furniture from trusted antique dealers (or having others built ad hoc) to decorate some of the large historic rooms that would form the pivot of what would be one of the first and true centers of conferences and events within a museum in Italy.

Between 1952 and 1955 the first donation: the collection of Francesco Mauro, an engineer, former parliamentarian, president of Cinemeccanica and professor at the Milan Polytechnic. Mauro, author of hundreds of publications, was one of the founders of the science of labor organization in Italy and the first popularizer of Taylorism in the years of fascist autarchy, a great traveler and connoisseur of the Orient and the United States, a friend of Ucelli and not coincidentally a member of the museum’s ordering committee. Together with his wife Edi, he had collected over the years an important nucleus of Chinese and Japanese works of art, and also, among other examples, a small nucleus of drawings, prints and paintings by Aldo Carpi, a family friend, and a valuable group of Deco goldsmiths, which includes some of the few works by goldsmith Alfredo Ravasco preserved museum collections (all wedding anniversary gifts, made by Francesco Mauro to his wife). To top it off, Mauro also left the museum his precious historical library, which fully restores the identity of this Milan Politecnica, combining texts on engineering and labor organization (hundreds of which he wrote himself) with volumes on Eastern and Western art.

|

| Alfredo Ravasco, Gold, enamel and topaz case (1925; Milan, Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci, Francesco Mauro donation) |

|

| Alfredo Ravasco, Perfume box in gold, semiprecious stones and rock crystal, with dedication by Francesco Mauro to his wife Edi (1925; Milan, Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci, Francesco Mauro donation) |

| <img src=’https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2020/1294/alfredo-ravasco-porta-profumo-2.jpg“ alt=”Alfredo Ravasco, Perfume holder in gold, semiprecious stones and rock crystal, with dedication by Francesco Mauro to his wife Edi (1925; Milan, Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci, Francesco Mauro donation)“ title=”Alfredo Ravasco, Perfume holder in gold, semiprecious stones and rock crystal, with dedication by Francesco Mauro to his wife Edi (1925; Milan, Leonardo da Vinci National Museum of Science and Technology, Francesco Mauro donation)“ /></td></tr><tr><td>Alfredo Ravasco, <em>Gold perfume holder, semiprecious stones and rock crystal</em>, with dedication by Francesco Mauro to his wife Edi (1925; Milan, Leonardo da Vinci National Museum of Science and Technology, Francesco Mauro donation)</td></tr></table> <br /><br /> <table class=’images-ilaria’><tr><td><img src=’https://www.finestresullarte.info/review/images/2020/1294/giannino-castiglioni-medaglia-sempione.jpg’ alt=”Giannino Castiglioni, Medal of the Simplon International Exposition (1906; Milan, Leonardo da Vinci National Museum of Science and Technology, Johnson donation)“ title=”Giannino Castiglioni, Medal of the Simplon International Exposition (1906; Milan, Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci, Johnson donation)" /></td></tr><tr><td>Giannino Castiglioni, <em>Medal of the Simplon International Exposition (1906; Milan, Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci, Johnson donation) |

In 1953, Johnson, Italy’s oldest medal factory, founded in Milan in 1836, donated along with one of the hammers used in the first Porta Venezia factory a part of its medal collection, which included not only medals made in more than a century of activity, but also specimens from earlier periods and from international manufactures. Among these, also designed by artists of the Art Nouveau season such as Egidio Boninsegna, Ludovico Pogliaghi and Giannino Castiglioni, dozens and dozens of beautiful ones stood out that commemorated all the great international expositions of art and industry, starting with the Great Exhibition in London in 1851 and arriving, among others, at the great International Exhibition of Sempione held in Milan in 1906. It is no coincidence that it was precisely the Great Exhibitions of Art and Industry that laid the foundations in Europe for the birth of Decorative Art Museums and Technical-Scientific Museums, and Guido Ucelli also paid great attention to highlighting the excellence of those “Industrial Arts” in which the aesthetic quality of manufacture, its intended use, and the tools to make it had to somehow meet. This placing on the same level of importance the works of applied art (whether wrought iron works, wooden inlays, goldsmithing) and the tools of the trade was a great intuition of Guido Ucelli, who by 1958 inaugurated precisely a section on thegoldsmith’s art by exhibiting, alongside Ravasco’s oriental artifacts and goldsmiths from the Mauro collection, semi-finished items from the workshop of the same goldsmith, inherited at his death from the Milanese Orphanage delle Stelline, and tools and semi-finished items donated by Calderoni, one of the most important Milanese jewelry shops of the early 20th century.

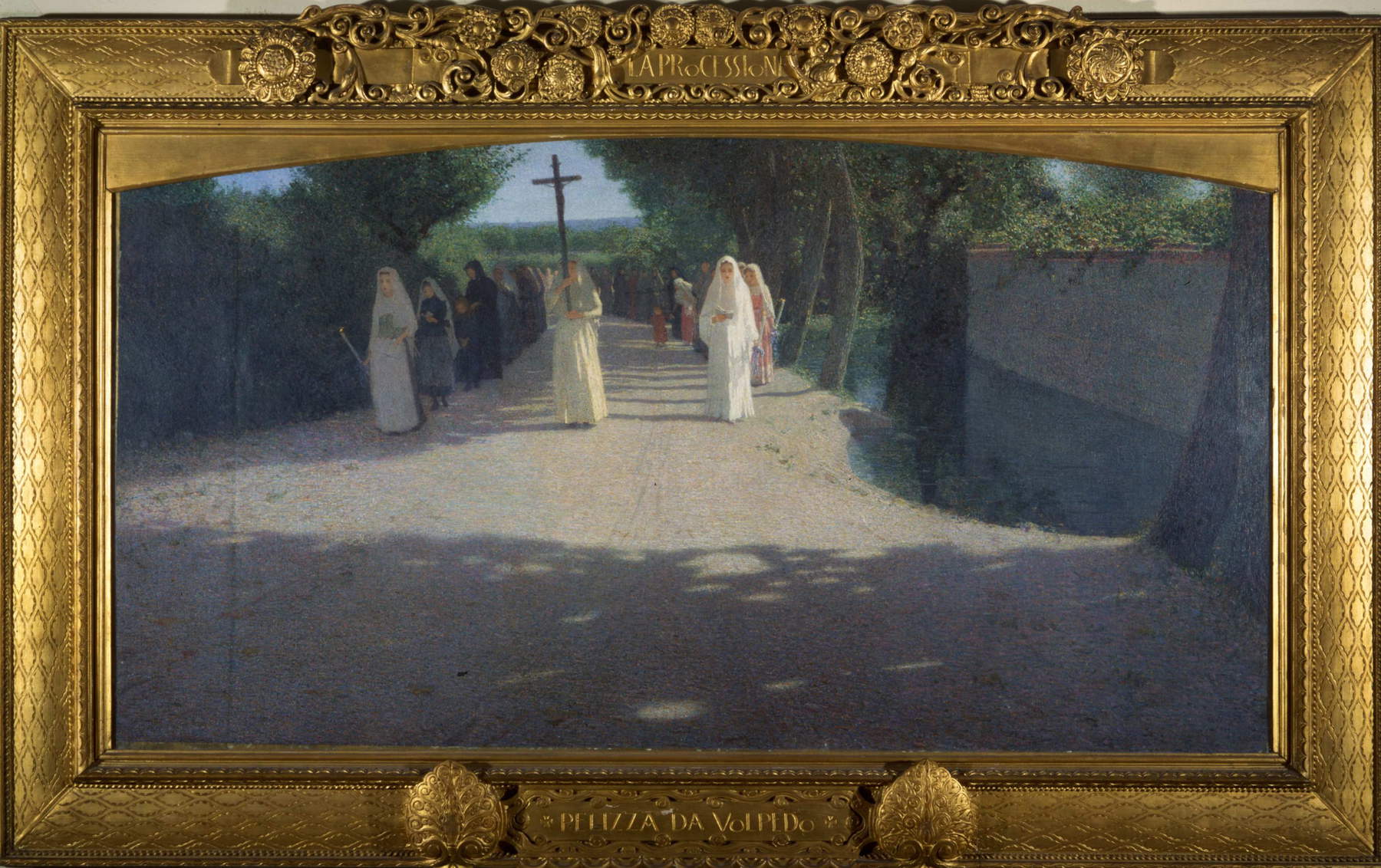

This first important phase of art acquisitions was crowned by the arrival in 1957 of the collection of Guido Rossi, a textile industrialist of the same age as Guido Ucelli, who was born in Gallarate but moved to Milan in the early twentieth century. Rossi had been president of the Brusa company and owner, along with Giuseppe Chierichetti, of one of Milan’s most famous Art Nouveau buildings, Giulio Ulisse Arata’s Casa Berri-Meregalli, in the Porta Venezia district, his Milanese residence. His collection was aligned with the tastes of the industrialists of his generation, as we have outlined, favoring artists of the second half of the 19th century, starting with painters from southern schools such as Filippo Palizzi, Antonio Mancini, and Francesco Paolo Michetti, purchased as early as from 1913, moving on to an important nucleus of painters of Lombard and Piedmontese realism and pointillism, with masterpieces by Filippo Carcano, Carlo Fornara and Giuseppe Pellizza, whose famous Procession, the Volpedo painter’s first pointillist work, presented in 1895 at the I Venice Biennial, Rossi managed to acquire, among others. Although not numerically representing an important nucleus, Rossi also managed to acquire two important works by Macchiaioli artists: Silvestro Lega’s I Fidanzati, a masterpiece from the Piagentina period of 1869, and Giovanni Fattori’s Campagna Romana. Rossi’s collection does not lack examples of artists contemporary with him, such as an important nucleus of paintings by Pietro Gaudenzi, sculptures by Arrigo Minerbi, and two works by Adolfo Wildt, an artist whom Rossi got to know during his frequentations of the Galleria Pesaro in Milan and to whom he also entrusted the execution of the enigmatic Winged Victory for the atrium of Casa Berri-Meregalli, fortunately still in situ.

|

| Silvestro Lega, I Fidanzati (1869; Milan, Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci, Rossi donation) |

|

| Giuseppe Pellizza, The Procession (1892-95; Milan, Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci, Rossi donation) |

To tell the truth, a common denominator of these important acquisitions in the early years of the Museum’s life was the unaccountability of not bothering to also acquire the personal archives of the donors, which could have been a valuable documentary source for the history of the collection and the works. But at the time it was perfectly normal not to give importance to these historical aspects, so much so that in the exhibition of the works at the Museum in 1957, the names of Francesco Mauro and Guido Rossi merely appeared at the entrance to the relevant rooms.

In the last ten years, work has proceeded with the reconnaissance, preservation and restoration of many works, but above all with their study and cataloguing, accompanied by documentary research, which is still in progress, in order to reconstruct their histories, identify connections and reassemble fragments. Today, most of these collections are not on public display (but can often be seen on loan to exhibitions), but the goal for the future is to return to reexhibit them with a curatorial project that accounts precisely for the reasons for their presence within a scientific museum, making evident the interconnections we have traced between technique, industry, collecting and history.

The author of this article: Claudio Giorgione

Storico dell'arte, è curatore presso il Museo Nazionale della Scienza e Tecnologia di Milano.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.