In the pleasure dome

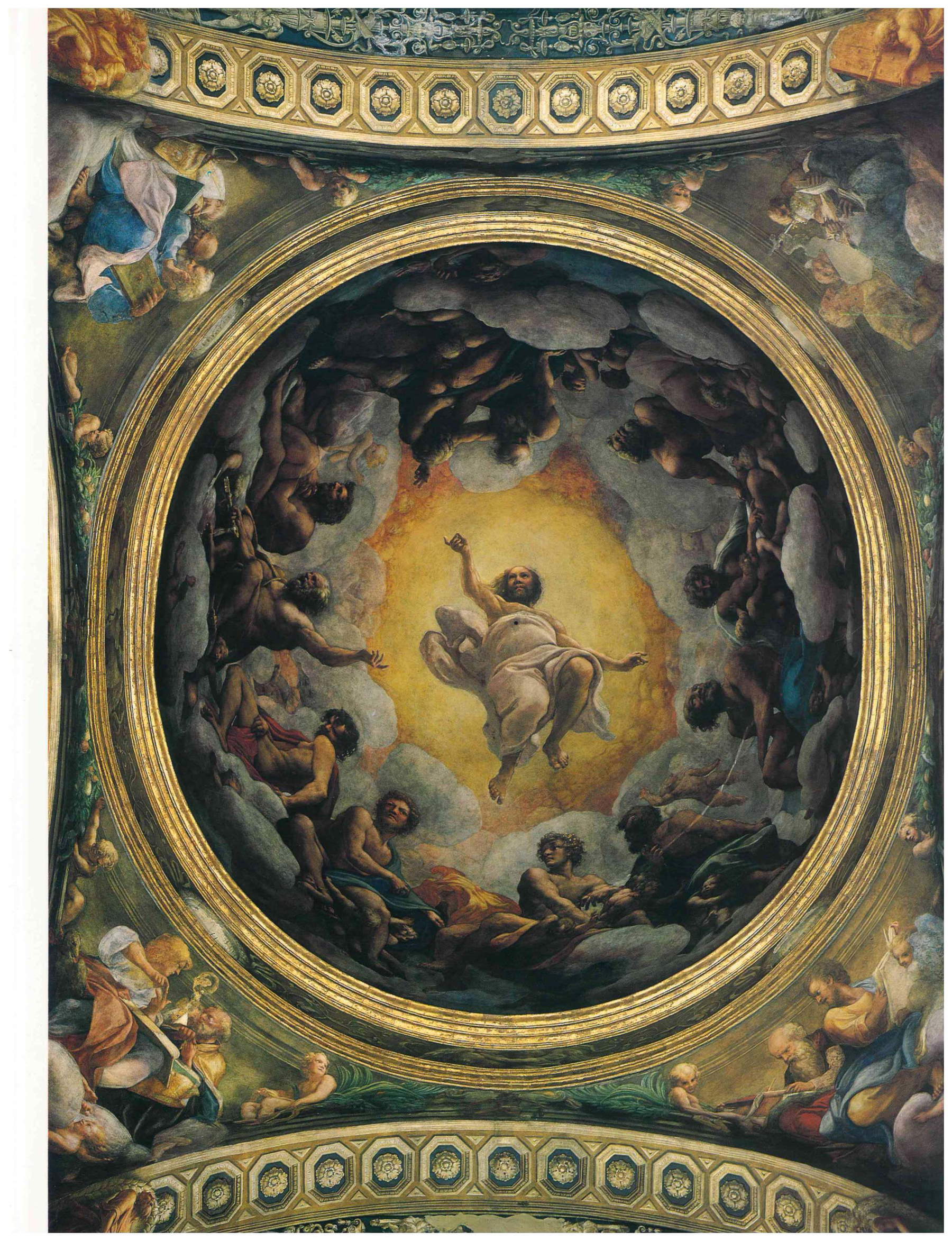

We publish below, as anticipated inBruno Zanardi’s article last May 18, and after the article written by Francis Haskell, the one written by Alberto Arbasino for the book that Guanda published in 1990 on the occasion of the restoration of Correggio’s frescoes in the dome of San Giovanni in Parma.

After Stendhal’s “divine! divine!” (“what seductive grace! what heavenly grace! the grace of expression combined with that of style! a miracle! it is music and not sculpture! étonnant, charmant, irrésistible, sublime!”), how many decades of cringing and frowning: Correggio too graceful... Correggio prissy... Correggio corny... Sleazy Correggio... Correggio mannered... Madonnas and culatos... Slick Correggio...

But That Famous Light Of Correggio - soft eroticism of complexion and skin like youthful autumnal fruit, to be touched - seems to spread a musical enchantment and poetic warmth less and less garrulous, or coruscating, or Kitsch, traveling under northern skies, from Vienna to Dresden to Berlin, amid duller, earthier cheeks, and less peach or apricot jam, or elegy. And those illustrious picture galleries seem warmed as well as illuminated by the wall of Correggios, as by a flashing fireplace in the row of dynastic salons. Even among sublime company: the fluffy Io in ecstasy like a Saint of Orgasms caught by the springy paw of a cloud King-Kong (with a sense of réclame for convict scents); and Ganymede leaving the dog puzzled by the explicit eagle (like the first time a succulent little one let’s a big one with candy take him behind the bushes) - hanging in the Hapsburg Kunsthistorisches Museum next to Parmigianino’s other little angel that sticks out its no-longer-innocent behind as sawing a stake or inflating a bicycle tire. (But the adjoining St. Paul has not fallen, as it would seem, because it has punctured, but rather snubbed by the haughty, heraldic cavallone, with such an elegant little head: an equine mise-en-abîme...)

What Italian, for that matter (even an unartistic one), will not be ready to divide himself between “impudichi et dishonesti” loves and a wife “who is a true saint to put up with me”?...And from the sensual ee gallant collecting of Rudolph II (old Prague...), to the devotional altarpiece sampler of Augustus III (old Dresden...), already in the context of the four Correggesque Madonnas in that supreme Saxon Gemäldegalerie one understands a character of “our Antony” in common with authors who instead of rewriting the same novel thirty or forty times continually change thematic and technical approaches, such as for example Thomas Mann from the small formats of Tonio Kröger and Death in Venice to the vast cone domes without pendentives, such as Joseph and his Sisters Brothers and Doktor Faustus. ... Morning shovels of “outside day” and night shovels with limelight; shovels with few still people as in Castelfranco Giorgione, or with several saints in elegant movements, such as Dosso Dossi’s Giorgio and Michele, which are there close by, in the three dresdens halls of the mind-boggling collectible slalom between Raphael’s Sistine Madonna and Botticelli and Mantegna and the Venetian maxima, passing and repassing between Cosmè Tura’s Sansebastiani and Antonello da Messina’s Sansebastiani that serve as wings.

In Budapest’s triple museum parthenon, after a disproportionate staircase, in a verandah of madonnas beyond a hall of dark, Leonardesque Lombards, the Correggesque one suckles the Child very profusely beside a dubious Barocci and vis-à-vis Raphael’s Esterhàzy. A very devotional collective or ensemble: underneath the madonnas thread one imagines children’s cribs and goodnight kisses. But also a “ladies’ breakfast,” since the only man there is a young Pietro Bembo portrayed by Raphael, as precisely in a ladies’ lunche where there is one man for every ten women because managerial husbands have told each one “you go,” and they are at the table with only one talk show scholar.

In Berlin, however, at the end of a rather long hall, dear Leda has traveled more than many of our worldly aunts put together, hasn’t she? To Mantua with Frederick II, to Madrid with Philip II, to Prague with Rudolph II, to Stockholm with Gustavus Adolphus, to Rome with Christina, to Bracciano at the Odescalchi, to Paris at the Orléans, to Berlin with Frederick II of Prussia, Gonzaga’s namesake, to Paris again with Napoleon, then back here in Dahlem. And after so many different companies, now the immediate competition here in the salon will result on the one hand with Titian’s Venus to whom the curly-haired musician goes playing the organ in pastoral mood... And on the other, with the nervousness and restlessness of the Farewell to the Mother of a Lottish Christ (“Mother... oh mother, farewell!” “Manrico!... Where is my son?”... “To death and the runs! ...”) in the discomfort of a symmetrical porch full of movement but open to all winds. And a Prado catalog may say that Correggio, “aunque no sea propriomente un manierista, lo mismo que Sarto, su pintura anticipa este estilo.” But around this Leda with her lively and beautiful “cygne d’autrefois,” certain smaller ledinas raise younger birds in a Swan Lake that undoubtedly pulls more to the point than Tchaikovsky’s.

Tourists d’autrefois, attempting a visit to the Correggios in today’s Italy, could perhaps tell that the Danae no longer dwells in the sinister and landslide Villa Borghese almost like Dresden under bombs, and will emanate a perhaps silvery glow and no longer “so yellow when it is yellow” after the restorations, while the Martinis and Christs and Madonnas of Emilia reside accumulated or stacked in an ephemeral and metallic cul-de-sac, at the National Gallery of Parma renovated and remansarded like a Pavesini where one has to walk miles of ladders and U-paths among the gigi rats in order to get a coffee. But arriving in Maria Luigia’s capital city, a sentimental art traveler will first of all be enchanted by the inventions and whimsy of the Camera di San Paolo, a post-Gothic parasol of greenery and neo-pagan gazebo for a singular Abbess with an evidently strong spirit, a Frances Yates of the 1510s.

Other than those Jeanne Moreau sheepish nuns between Diderot and Monza.... Here the heads of the Ionian abbeys still fresh from the undertaker’s bench stretch with the volutes of the horns-capitals the napkins that hold up the “good” table services just below the mythological and otherwise classical “conversation pieces” that will give a thematic start to the causerie at breakfast. And further up, to be looked at while sitting, an anticipation with enlargement of that elementary but sublime expedient of erotic voyeurism later variously called “oeil-de-boeuf ”or “glory hole,” and equally appreciated by Marcel Proust as by the paraculets in the booth at Ostia: sexuality being transferred and concentrated from the usual organs deputed to it into a Gaze that “penetrates” through a “hole” that is not carnal but optical. Even exalting as “Dionysian” what without the Forum and the Obstacle could be traced back to that model of weekday anticlimax that is the nudist beach, without streamers or hedges.

Within the oculons of greenery in the high gazebo, the movement of the correggesque babes may prompt questions about motivations and destinations-nowadays one would say the target audience-because they are rather developed, experienced, and wingless. Not “holy asses ”or “golden” to tenderize mommies of sweethearts, and push them to mindless purchases of baby powder and fluffy family-type toilet paper. Not yet, though, that first thread of beard with change of voice that heralds forthcoming-though inexperienced-satisfactions for the lady: themes mostly played out by Colette and Gide, i.e., if the good seed doesn’t die will come up the budding wheat, and we are there ready. “To change the green meadow / Into a forbidden play. / I tried, / But did I succeed?” (Sandro Penna). Perhaps those cheerful asses at the most critical age for the growing child were not really meant to delight an eccentric lady with sodomitic tastes. Perhaps the sage and worldly Abbess Piacenza showed rather a polite regard for certain of her friends who came to make conversation: old sodomites who were dowdy, provincial, up-to-date, dandy, perhaps secret collectors of who knows what jailbird Sansebastians, perhaps gastronomes accustomed to the joke about Culatelli and Felini with the son of the charcuterie man who understood everything “so shall we make good weight?” But proud, though, of their friendship with the Lady-one of the few salons that can still be frequented-and no less assiduous with their little gift at the first communions of the villagers’ little ones. “Such good gentlemen with the youth!” very conservative and well-meaning. And since Parma seems to have changed very little over time, their amiable conversations can be well reconstructed, perhaps. How many elegant similarities (have you noticed?) between Stendhal’s affectionate judgments of Correggio, and an astonishing forerunner of his (will he ever have read it?) that is Wilhelm Heinse’sArdinghello and the Happy Isles, 1787: a pre-Romantic, youthful journey-conversation through the most Renaissance and passionate Italy of “the three great apostles of art, Raphael, Titian, and Correggio” where “some miserable little town, rich only in a celestial painting by Raphael or Correggio, shines like a star in the face of the immense riches of the North, nocturnal deserts where no beauty appears...”And just in Parma, comparing Correggio’s Dead Christ already in San Giovanni to Raphael’s Borghese Deposition: “In my opinion, he has surpassed all and holds the first place like a Sophocles, so great are the severity, emotion and simplicity with which he treats the episode, renouncing his usual magnificence of color and his smiling manner. The divine youth, pale, bloodless, lies stretched out. Magdalene sits beside him, immersed in deep sadness, and sheds hot tears, like an inconsolable lover; the tender mother’s grief over her son’s terrible fate borders on the bitterness of death. A murky light envelops them; everything is life-size.”

But soon after, recalling the voluptuous Correggio: "Raphael, himself a martyr for Love, never expressed the delight of love-perhaps the highest subject for all the figurative arts-with the deep harmony of soul and serene imagination that manifested in his Io the great Lombard, without fame invites and Ariosto’s neighbor, even if he should have offered him occasion for it the small and ancient Leda with whom Jupiter mates in the form of a swan, an excellent and voluptuous group that you Venetians have placed just in front of the entrance to the Library of St. Mark’s as a demonstration of your free thinking.“..And a fixed idea: ”Ah, if Titian’s truth of color, Correggio’s light and shadows, Raphael’s high spirit, and Michelangelo’s knowledge of the human body could be united in one being, we would undoubtedly have the ideal painter, such as perhaps even the Ancients themselves never had." Sturm und Drang? Anti-Werther? Half a century before the Charterhouse of Parma...

Not for nothing is Ardinghello actually a young Frescobaldi in anti-Medicean exile between old Titian’s atelier in Venice and always incognito at a ball in Genoa where he ends up in the closet of the beautiful Lucinda, and... while she sleeps... “In front of a Madonna and Child, a copy of Raphael’s delightful Madonna della seggiola and the work of one of his best pupils, a lamp was burning; another was lit in front of a Magdalene, certainly the work of that great Lombard genius who was Antonio Allegri; there was an indescribable grace in the features of her face, a great delicacy in the color;her blond hair, painted in an unsurpassed manner, was as if deliciously moved by a light aura over her young breasts. In front of each painting was a flowering plant: in front of the Magdalene, buds and roses in bloom; in front of the Madonna, lilies and carnations that she herself had grown in winter. On a small table in front of the Magdalene, Petrarch’s poems, the necessities for writing...” And after numerous objective correlatives - erotic power of Correggio! Drop your pants, pre-romantic! - “in the end I was no longer master of myself. I shed my clothes and gradually approached with my whole body the most beautiful thing in the world. With the tips of my fingers I peeled back the shirt on either side, exposing the breasts that smiled at me with their innocent buds, as if begging to be spared in their virginity; I lifted the sheet from the dry, slender feet and beautiful legs to the middle of the thighs that rose upward round and opulent as columns, and under which it remained imprisoned....” (W. Heinse, Ardinghello and the Happy Isles, An Italian History of the Sixteenth Century, edited by Lorenzo Gabetti, Bari, De Donato, 1969).

Ardinghello also willingly reconnects Correggio with music. (But Heinse’s favorite authors are the same ones reevaluated by Riccardo Muti and Amadeus: Salieri, Jommelli, Traetta.) And how then Stendhal, who will favor Mozart, Paisiello, and even Cimarosa (about the Madonna of the Bowl). Is it possible to mystify oneself to such an extent? Excellent charades and quizzes for the Abbess’s elegant guests: which musician will most deeply correspond to Correggio? And by sovereign mythological suavity one should inexorably arrive at Francesco Cavalli, from Cremasque, but of whom Stendhal could not have known the sublime works - La Calisto, L’Ormindo - having missed all the Venetian carnivals at the theaters of San Cassiano, Sant’Apollinare and San Moisè, between about 1640and 1670, as well as the shootings between one beloved Mozart and another in those arcades of updated Stendhalism that are Glyndebourne and Santa Fe, where Cavalli’s baroqueOrion “en plein air” was transformed into a constellation up in the summer New Mexico sky...

And will it be La Calisto, because it brings together two such Correggesque themes as the Loves of Jupiter and the Hunting of Diana (there she is on the mantelpiece in St. Paul’s), while not for nothing did a Callisto by Dosso Dossi keep good company with Danae in Room XIX of the Borghese Gallery of yore? A love among the most “intriguing,” even for a Parmigianino after Fontanellato, since while Diana a little bit is lost contemplating Endymion’s sleep, Jupiter disguises himself precisely as Diana to seduce the nymph Callisto, who remains delighted and would like to start again with the real Diana. But she sassily retorts, “Hush, lascivious one, hush. What, what obscene delusion, doth thy wits confound thee? How immodest, whence, didst thou profane that bosom, with introducing into it such filthy lusts? What infamous harlot, can of thine, dishonest, form worse sayings?” And comes Juno to question her, “Other than kisses, say, did there intervene, was there, between thy Diva and thee?” And the bawdy nymph, “A certain sweet that, which I would not tell thee.” Having figured it all out, Juno turns her into a teddy bear, and Jupiter in turn into Ursa Minor (so many constellations for outdoor festivals!), while Pane certain satyrs behave very badly with Endymion deep in the woods (“Bound to the maple trees, let him be macerated,” etc.), and the Abbess Piacenza’s friends would have been delighted.

But more charades loom. In a letter to Balzac, recovered by V. del Litto, Stendhal claims that “tout le personnage de la duchesse Sanseverina est copié du Corrège.” But won’t it be Clelia, the most Corrège-like of all? And aren’t the Sanseverina and Fabrizio rather Bronzino, out of this area? One can go on for evenings and evenings....

And about Correggio’s “intriguing” trips to Rome or elsewhere, with what relish would one recall the controversies about Luchino Visconti’s trips to the United States, when he was making directions so identical to Elia Kazan’s Tennessee Williams that documentation could not have sufficed, one needed direct experience. However, it is known that Luchino had done all of America before the war, whereas afterwards sympathy for the PCI would have created problems...So how do you explain certain striking coincidences even for those who went to and from Broadway every year like Garinei and Giovannini?... In short, how difficult is historical certainty even about contemporaries: other than Vasari, when nothing is known about a “Nazi period of Luchino,” removed by family and old friends, however a source of the “rightness” in the last “Bavarian” films, elaborated on a first-hand but evidently immediate personal testimony, even if incognito.

And about the conjectures around the perhaps alleged iconographic programs of perhaps “casual” collectors, who knows how many comments and smiles: this year I put Rops’s etchings next to Klimt’s heliographies because it seems witty to me in the bathroom; this corner has a difference in formats because under Klinger’s centaurs go the tall bottles while under Fantin-Latour’s Daughters of the Rhine will come the low glasses...

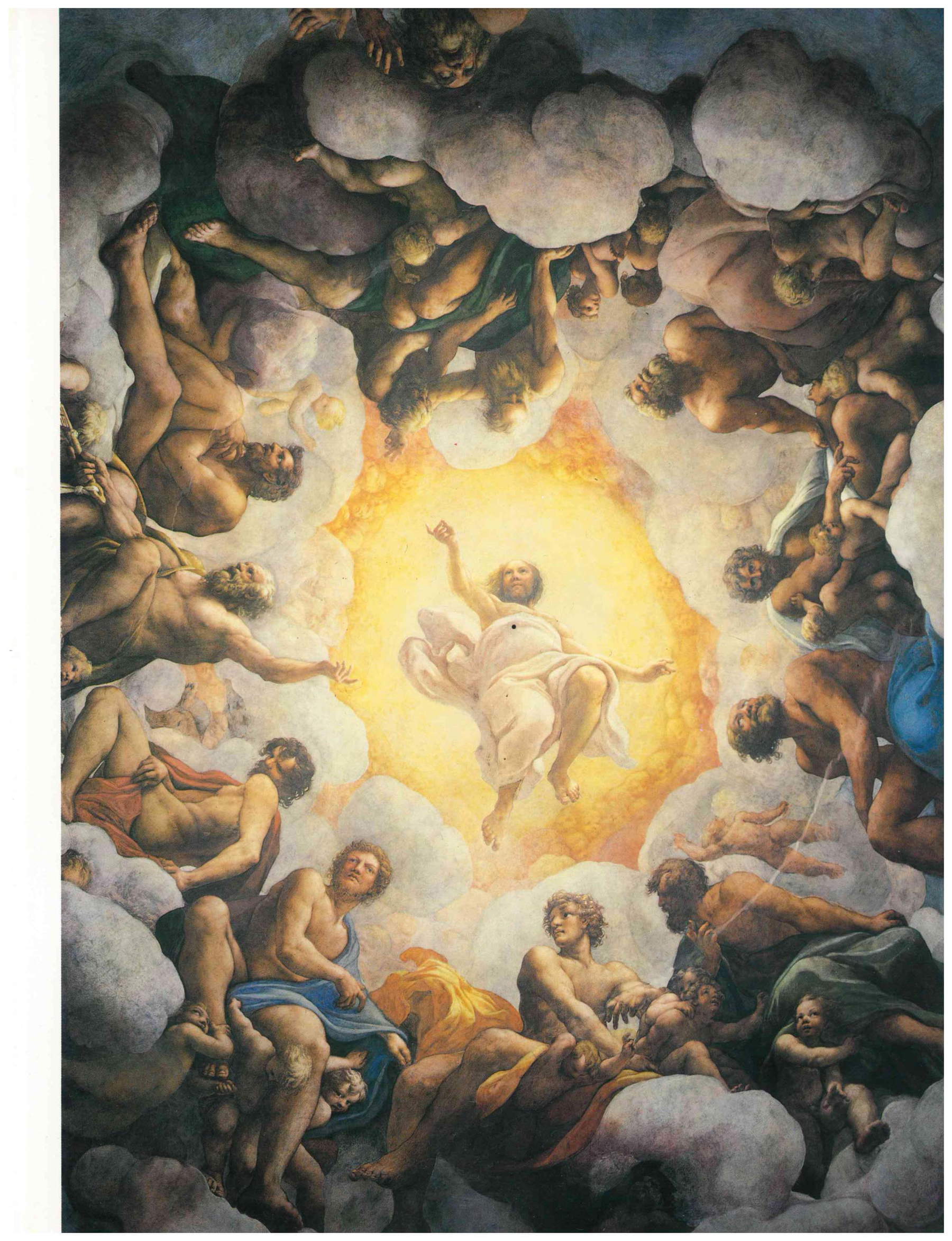

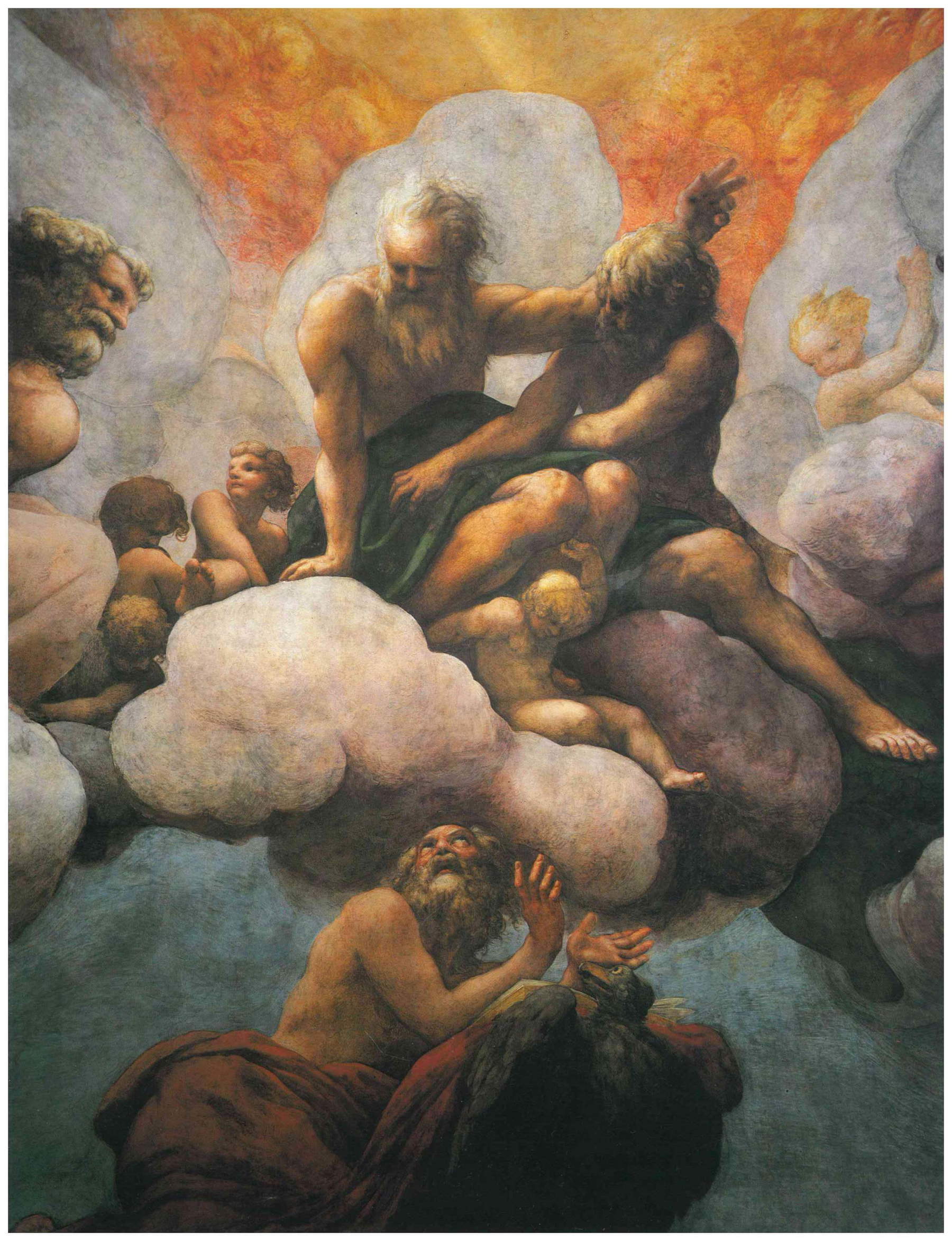

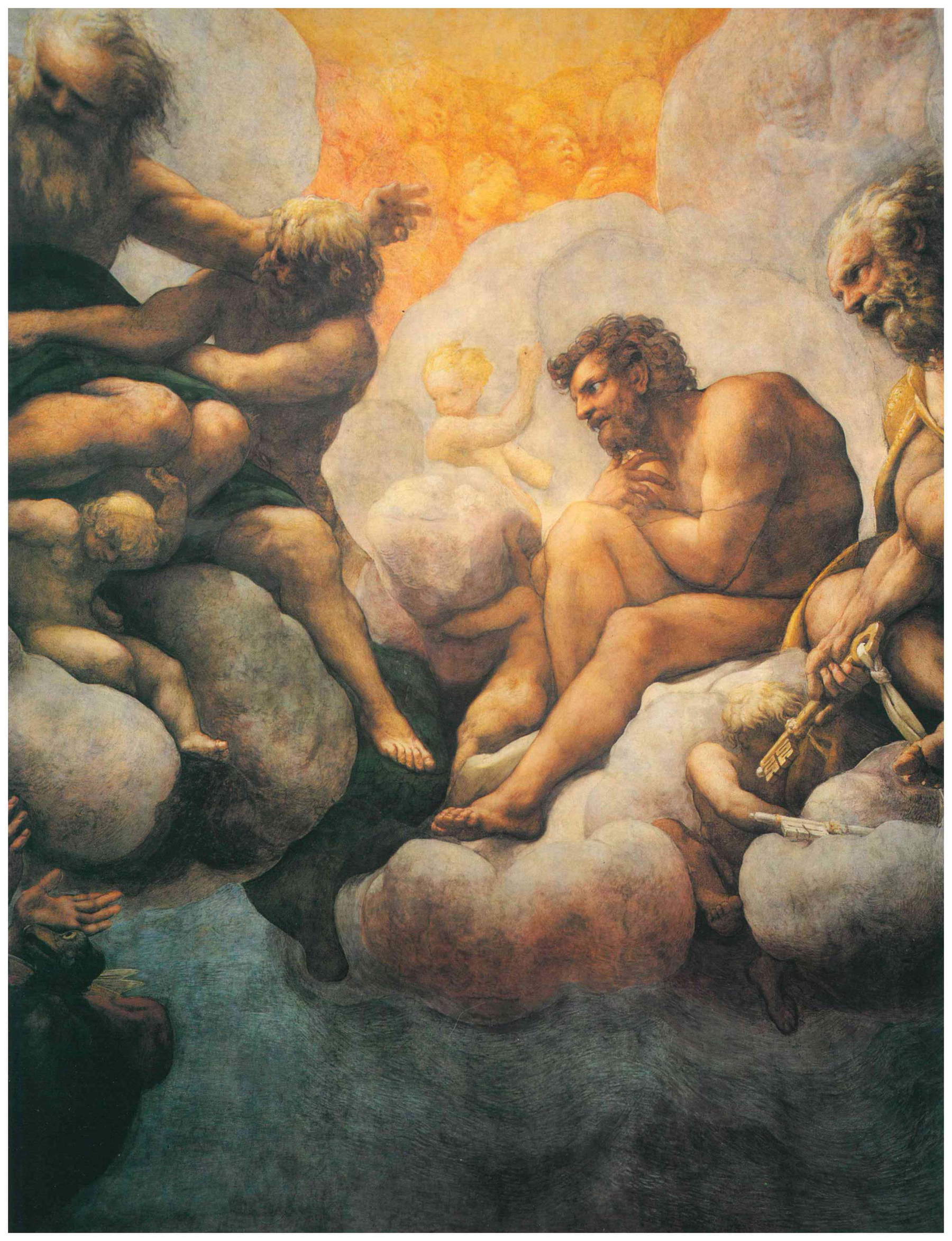

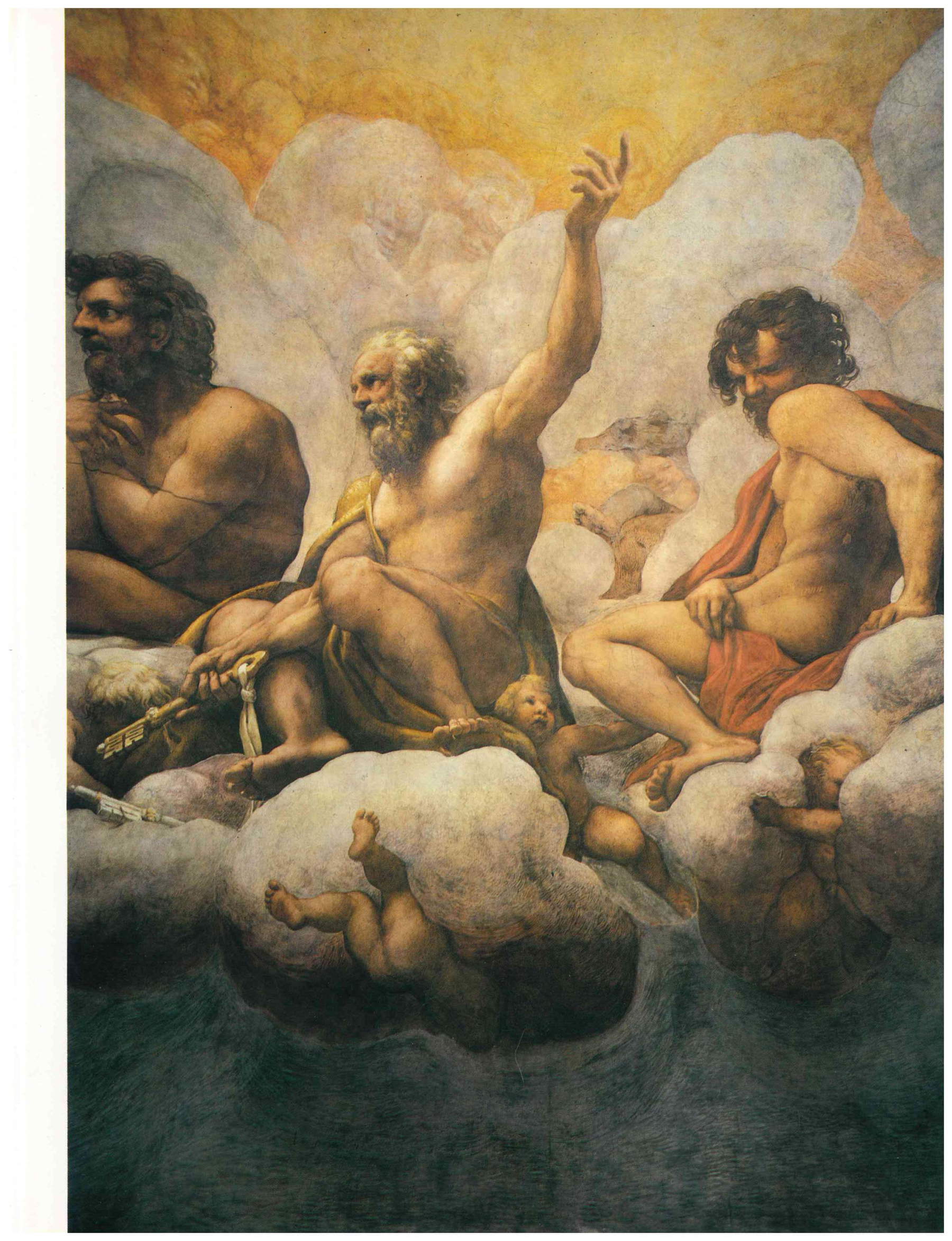

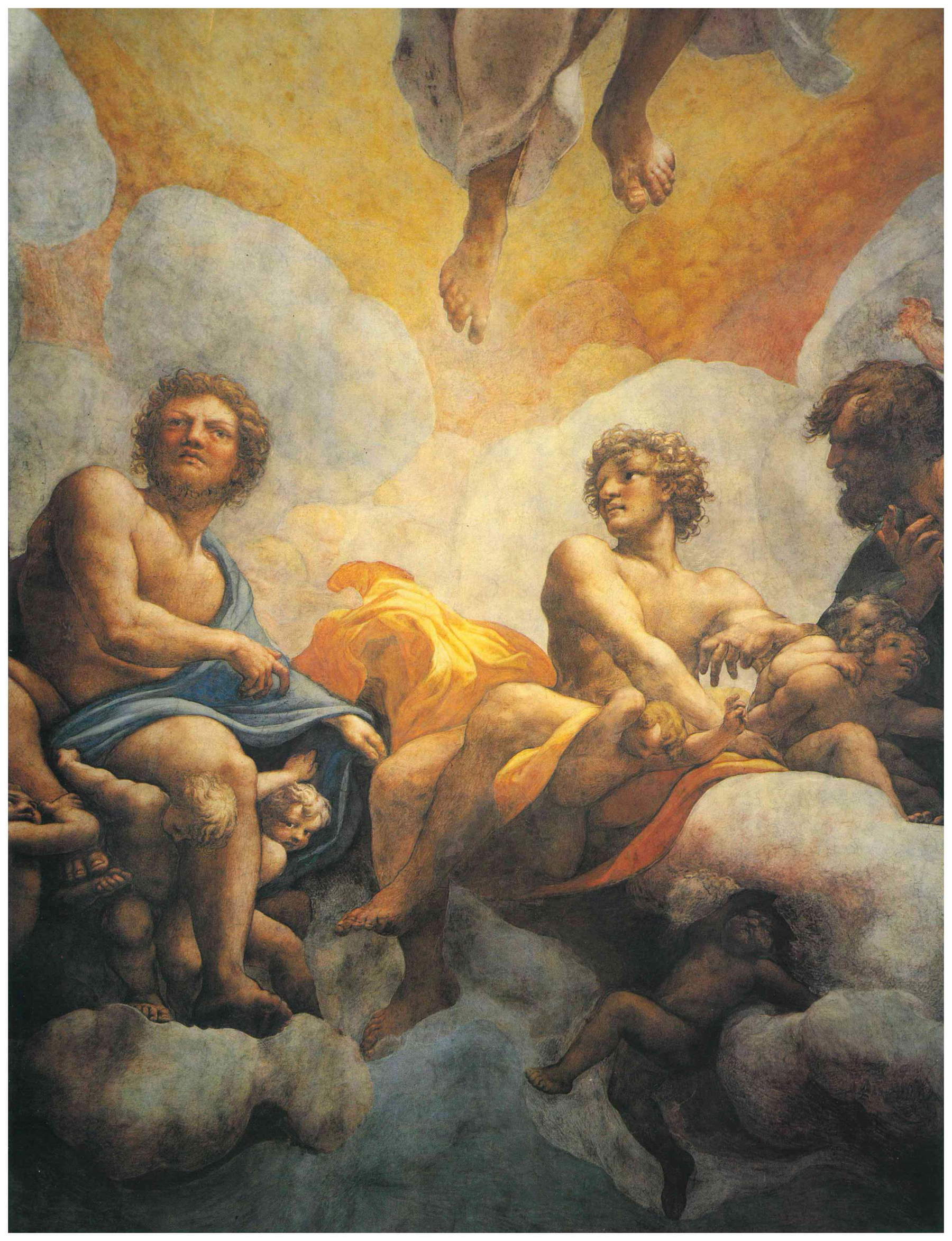

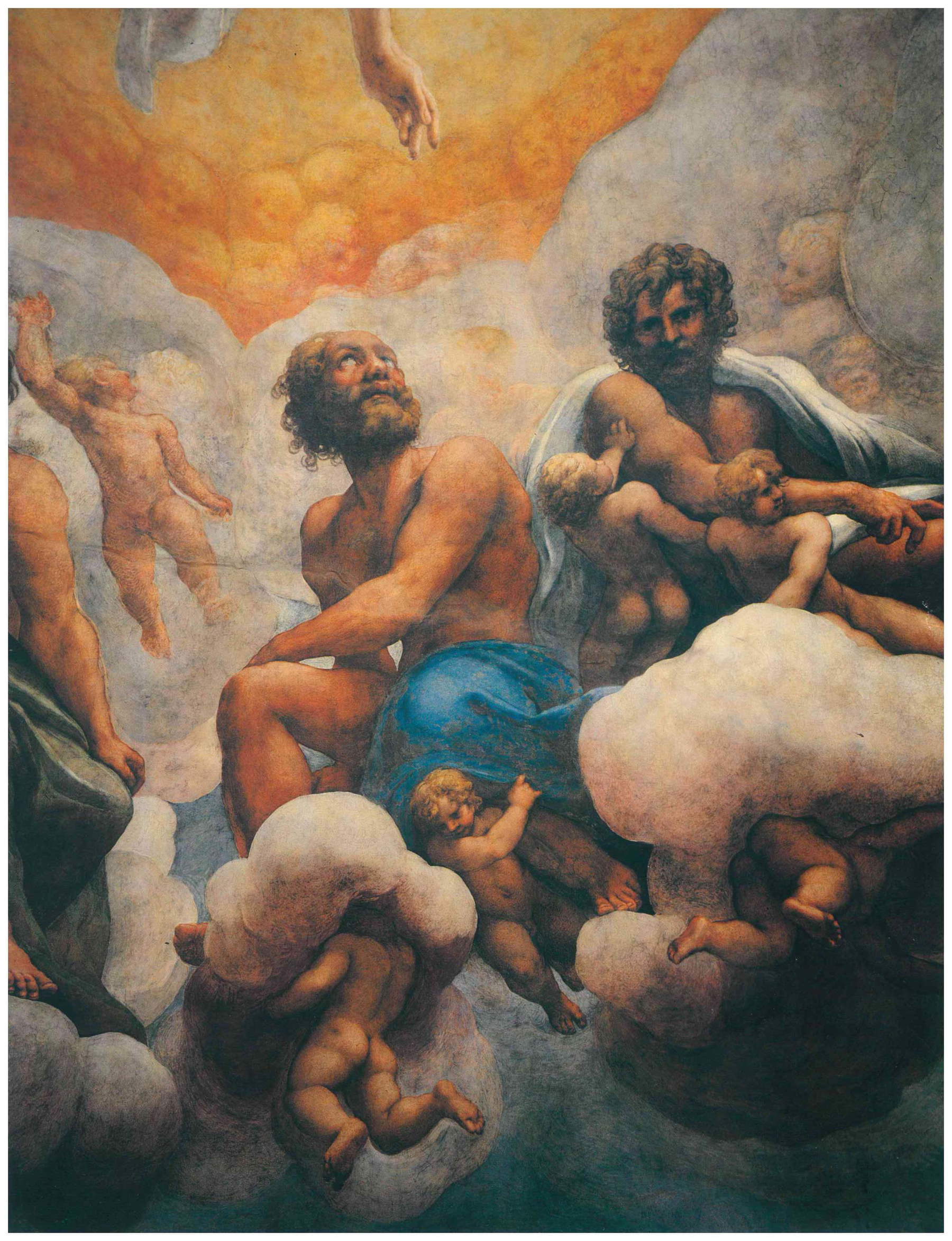

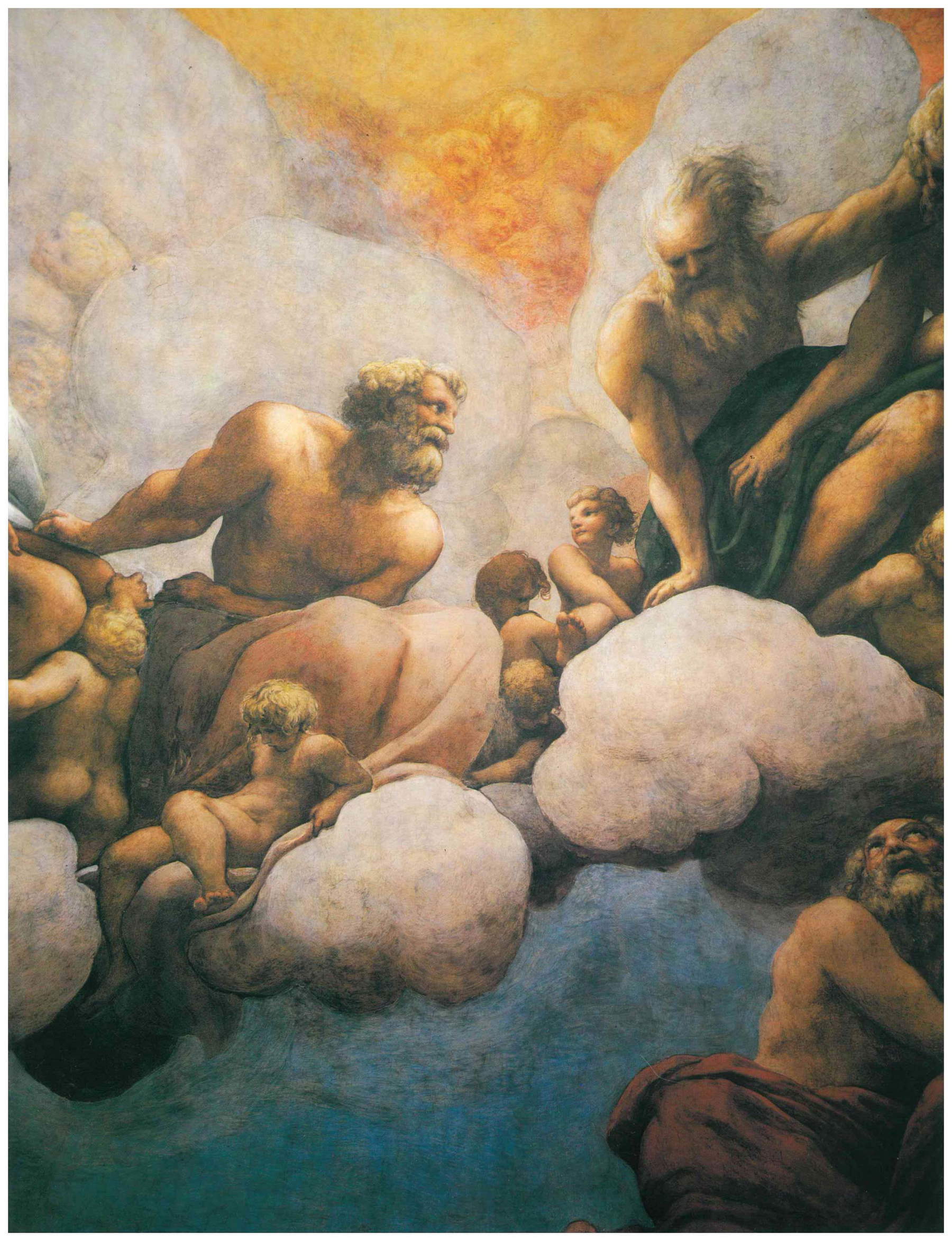

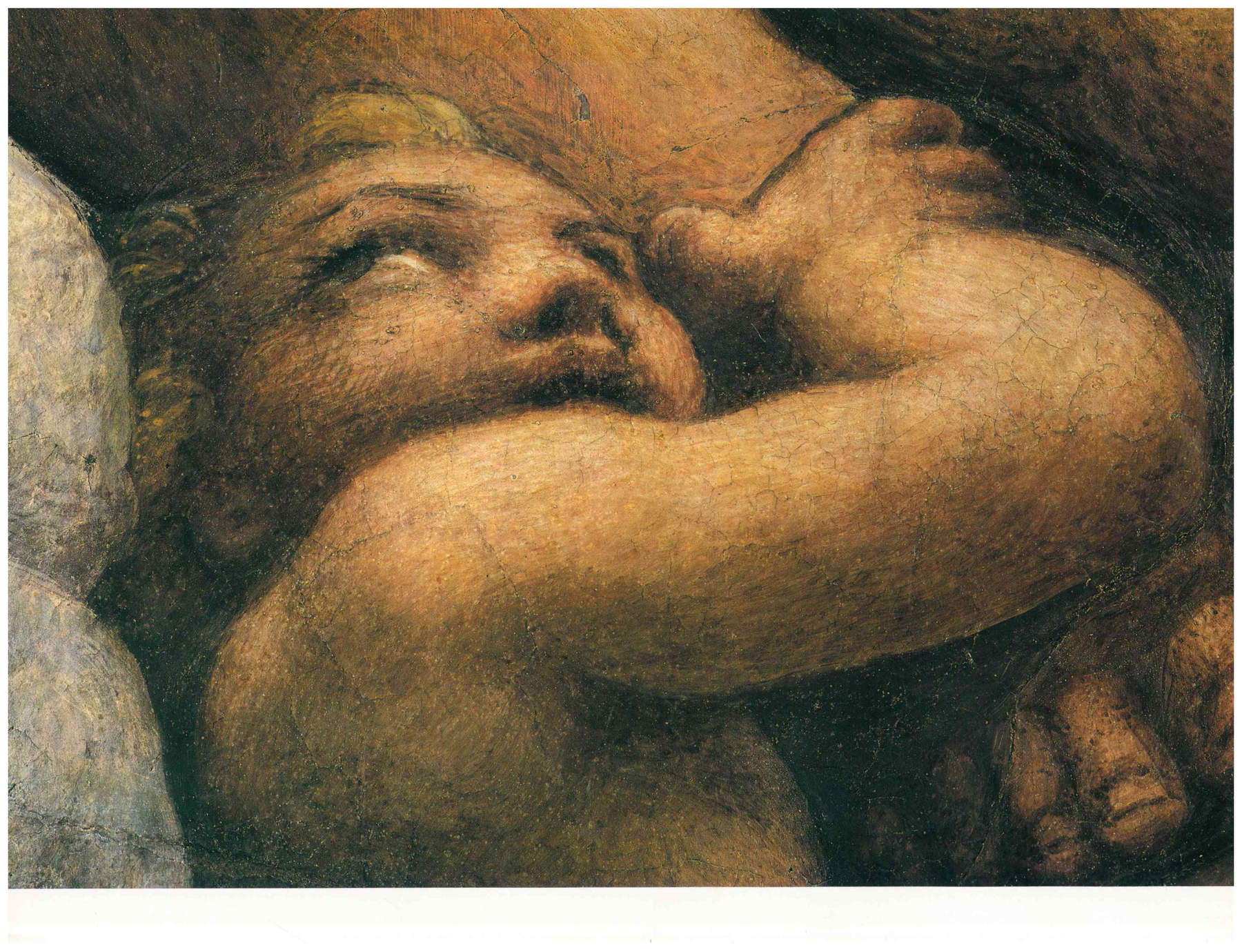

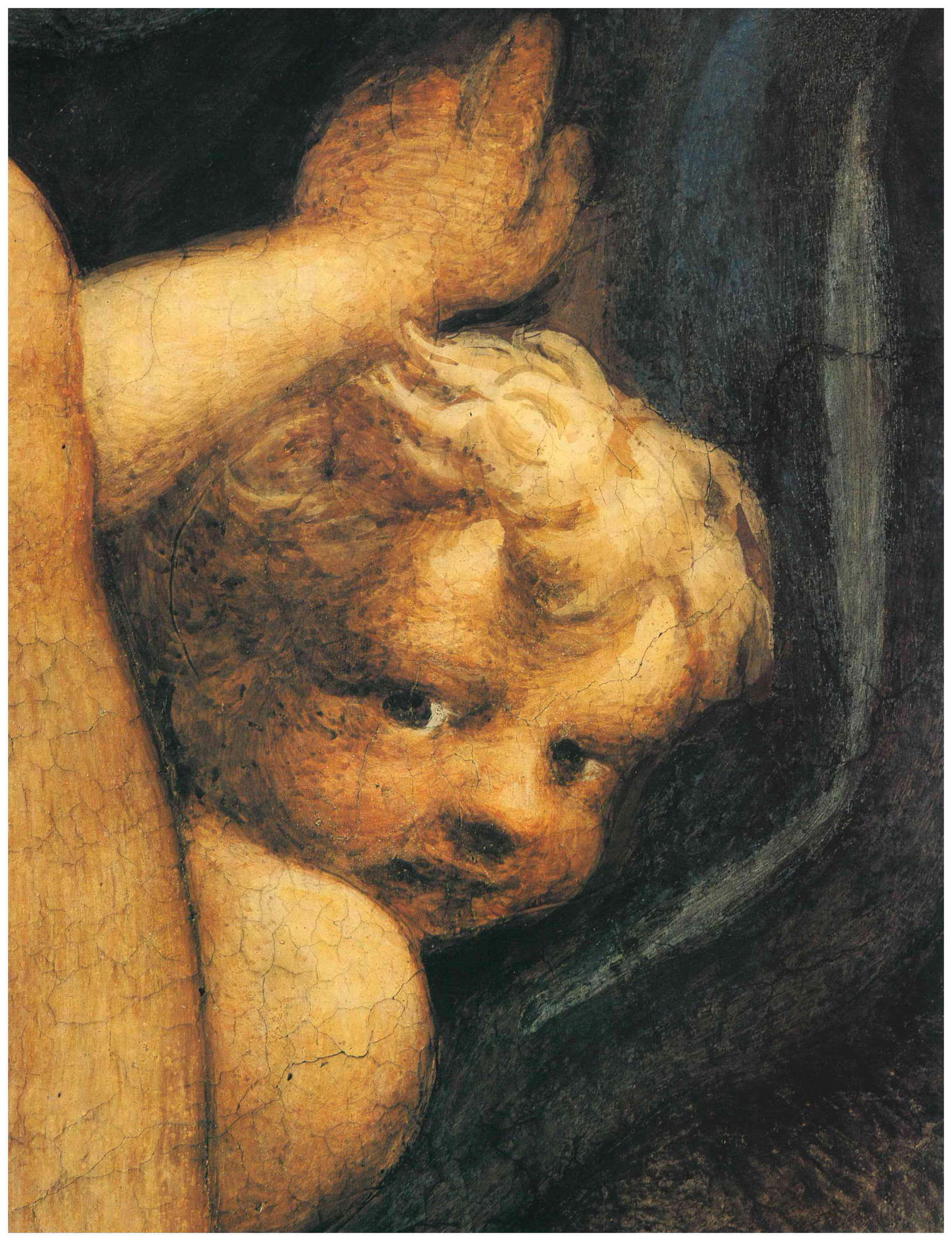

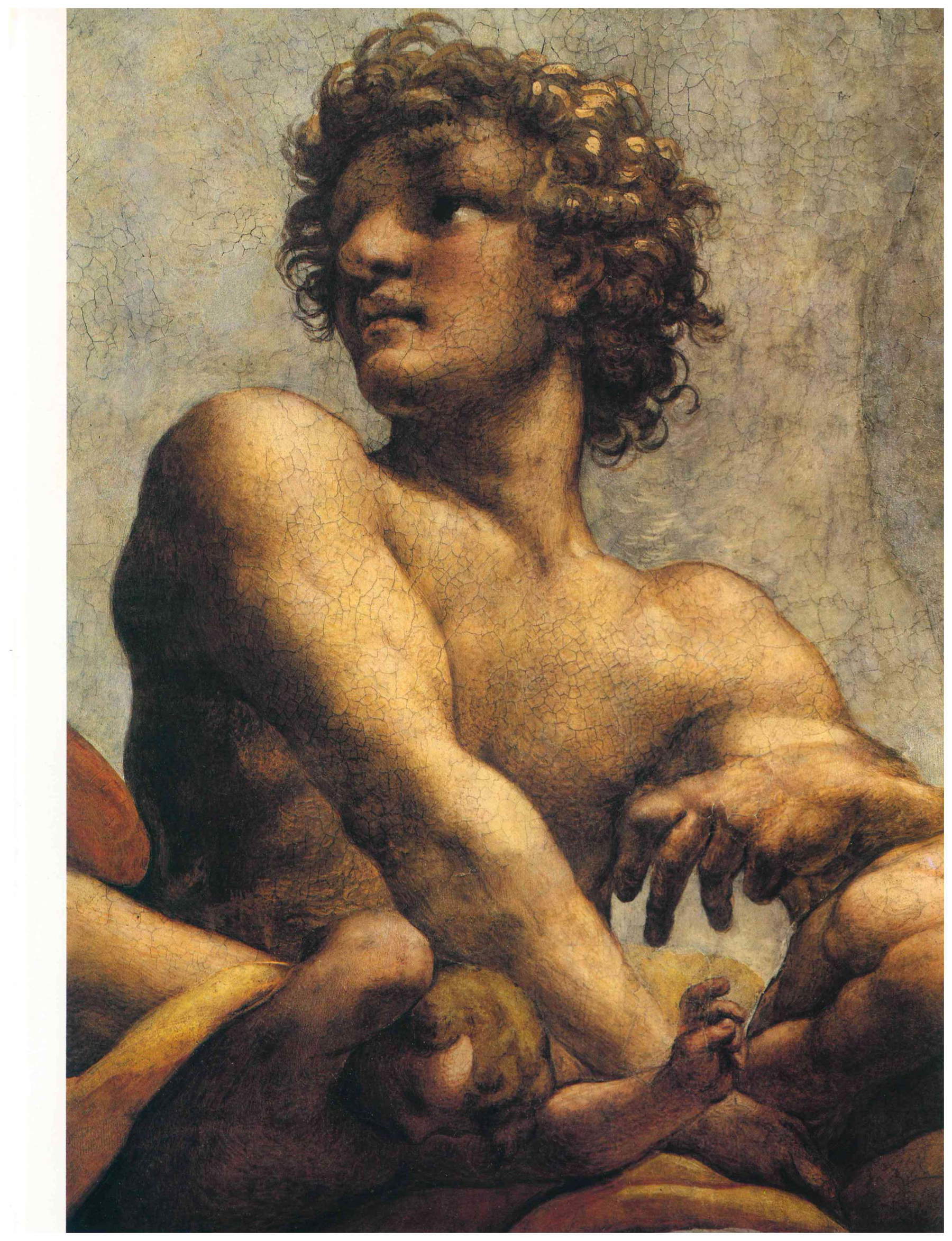

Nèi and cicisbei of the sixteenth century... in the intermittences of a Tangier or Patmos of the spirit.... Will they, in short, be the same old local friends of the Abbess, at different times of the day, those “ambiguous vigilants in robes next to wingless angels” (Longhi) on the dome of the friars of St. John the Evangelist, now restored to its splendor after centuries of invisibility through filth? amid the ambiguities of ancient art prose, for Berenson an emergence of Michelangelo in Florence, an appearance of Raphael in Umbria, an emergence of Titian in Venice, was “all but inevitable.” But by no means was it predictable, “in the petty municipalities of Emilia”-and in that petty commiserative “petty” is usually summed up all the meanness of the Universe-“the delightful flow we know as Correggio.” And the very curious noun “stream” (mica always “of consciousness”) mostly means a very consistent and very abundant liquid jet, referred to as “a miracle” in disused surroundings as “uninspiring.”

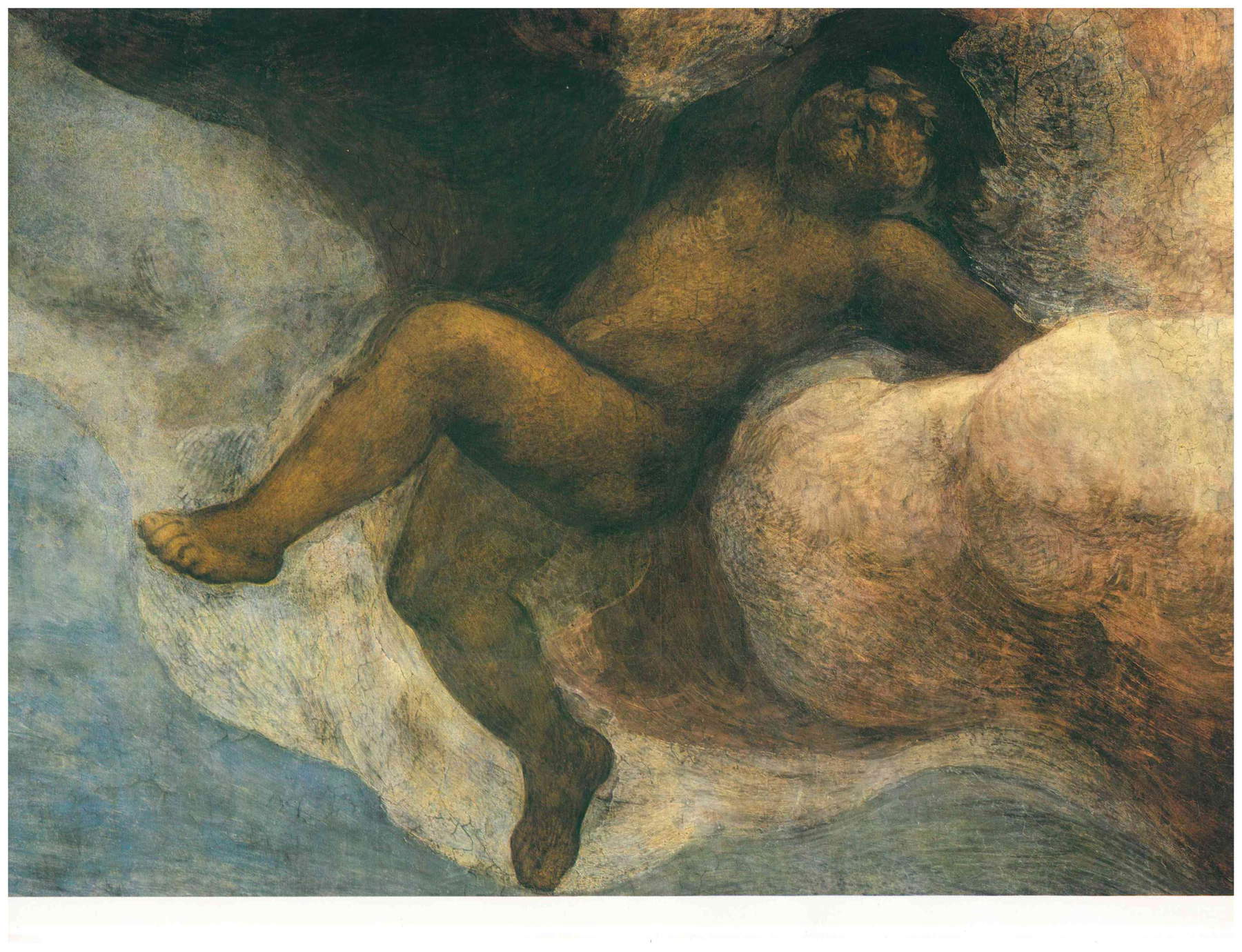

Yet Berenson identifies flow and miracle with the irresistible seduction of a charm so feminine as to anticipate the eighteenth century and aim “miraculously ” at the most exquisite Rococo... So, completely cutting out the impressive Giants of this dome, where the referents and competitions of an artist in his early thirties could mainly turn out to be the Sistine Chapel and its not at all gallant and chic homons. (And about Platonic or Platonic programs, impossible to forget what Maria Callas replied about the supposed Nietzsche in her dizzying Medea: “The greatest concern was the weight of the train, to make the folds fall right in the sudden turns on the steps.”)

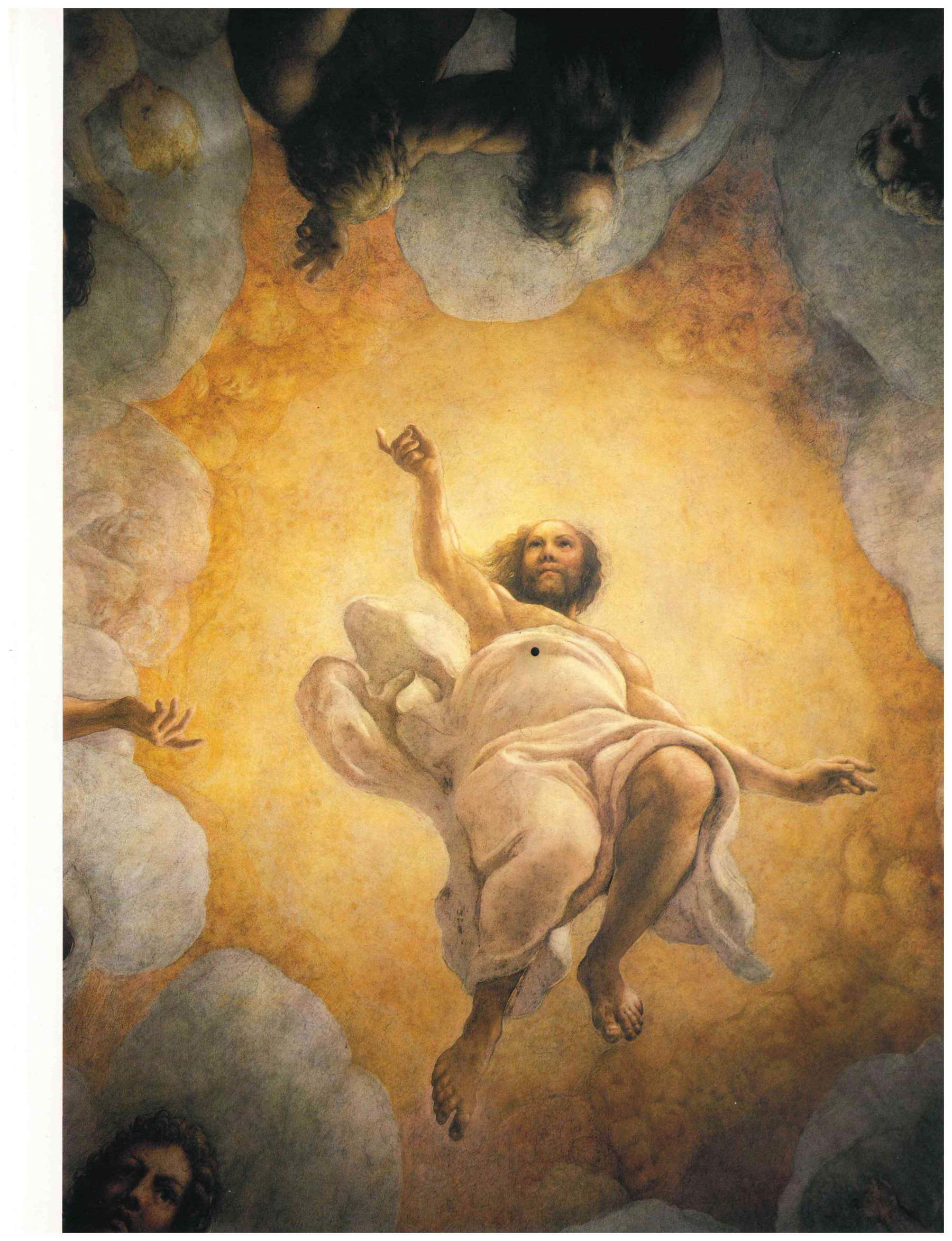

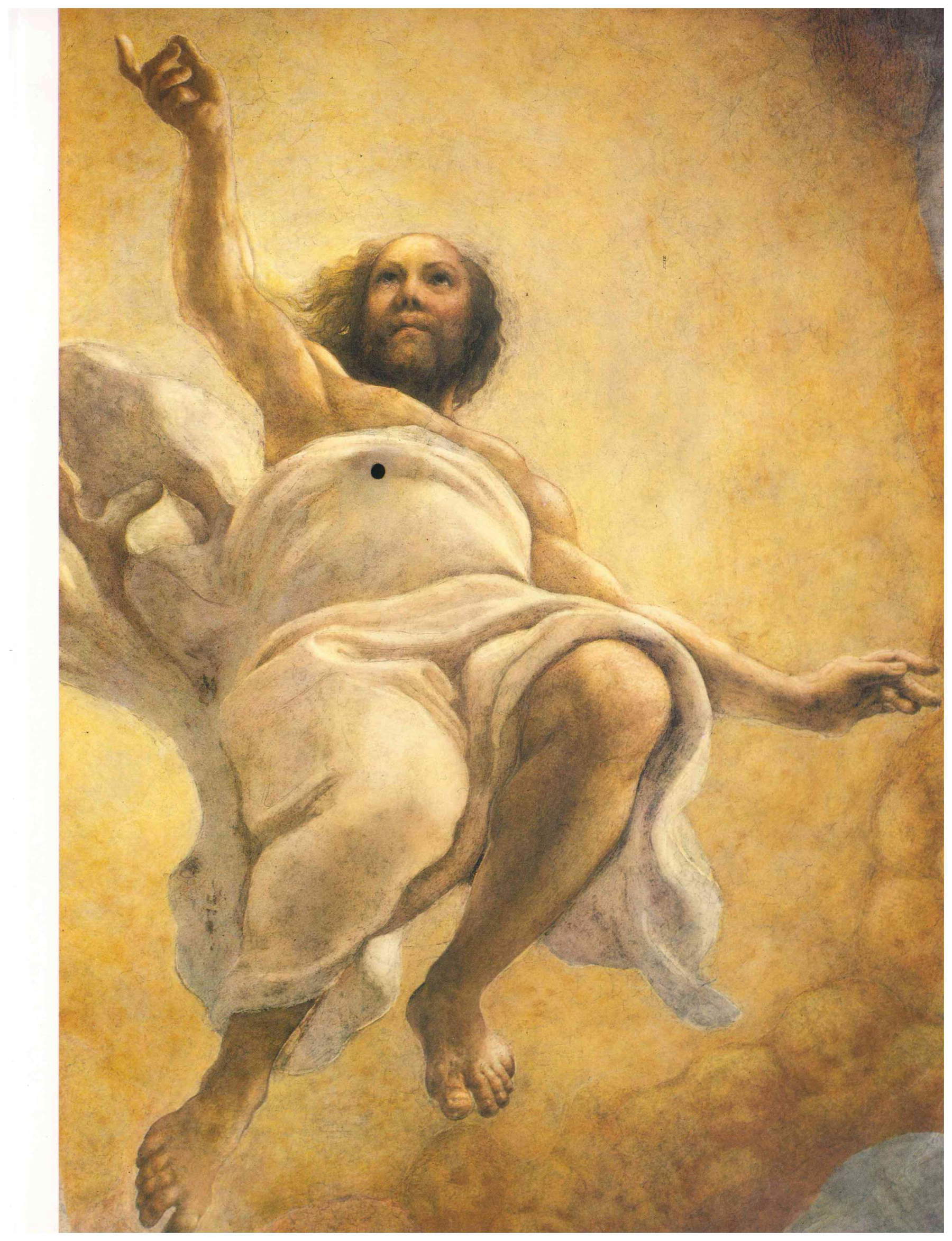

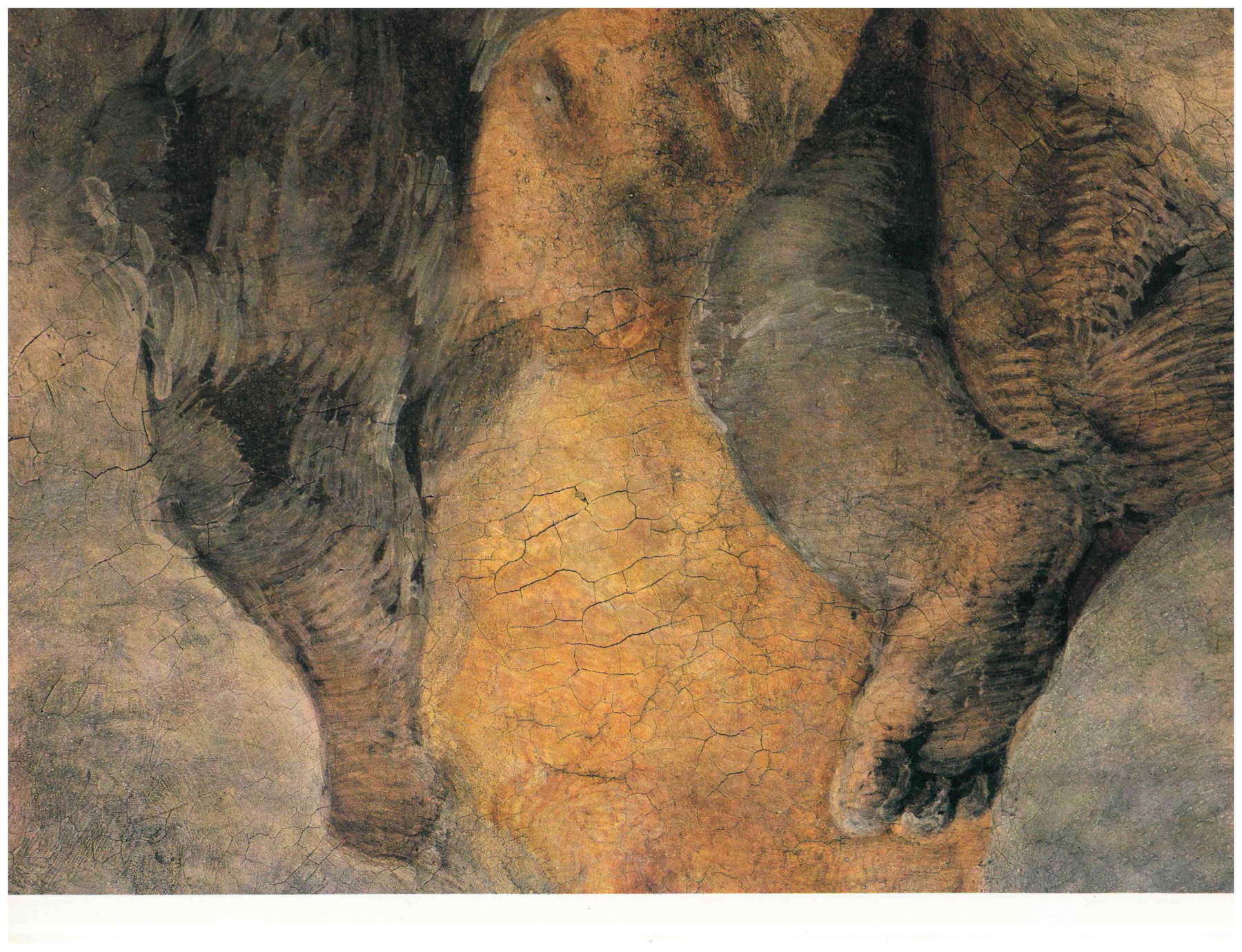

Ardinghello, on the other hand: “Correggio’s dome enclosing the Ascension into Heaven of Christ in the church of San Giovanni in Parma belongs to a special kind of pictorial tactics and is a work in itself which for pictorial effect one cannot compare with that of Raphael without doing him wrong. One is astonished, if one stands under the dome, nailed to the floor as if by a spell, and watches a young man of this earth, with supernatural attributes, ascend to distant heights, carried by stormy, helpful winds that play caressingly with his broad purple cloak.”

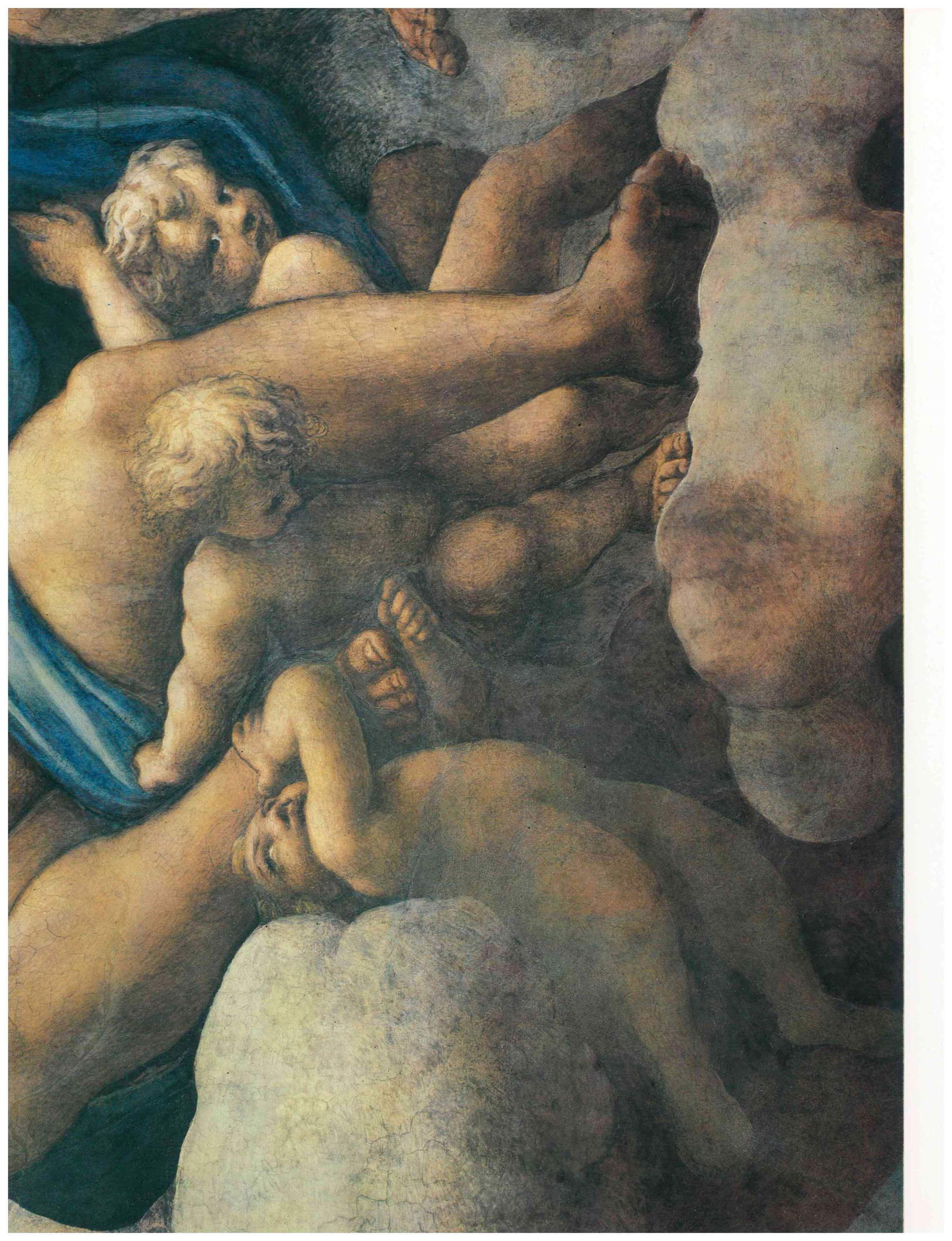

In the prose of the pre-Romantic youth, one can thus feel the grip of the elegant illusionistic artifice whereby from the side of the audience (i.e., the faithful) Christ’s flight actually appears as an Ascension: and in fact the young James the Lesser, having already taken leave and bid farewell and exhausted the pleasantries, is turning elsewhere, already distracted, without lingering to wave bye-bye as at the station until the train has disappeared around the bend. Instead, on the choir side, the monks could glimpse the optical reverse of the omelet, and an opposite situation: this shabby-looking old man - John the Evangelist in Patmos - already submerged and crushed in who knows what up to the waist (by punishment? by anamorphosis?), like an Atlas of William Blake or Samuel Beckett, now dumb and despondent and Fin de partie after repeating the thousand times, “all the weight of this stuff must rest on my shoulders, while you go about night and day having fun.”..And the unhappy old man sees this rather dreadful thing: a depressed old Jesus (the steaming thirty-somethings of yesteryear...) falling head over heels disheveled and bewildered on his side, not like those aviatrix aviators who in 1930s movies glided laughingly over a pile of hay there ready, but without looking his down and without minding the direction...

Thus, probably, John being an apocalyptic and a visionary, chilling certain fears about the future, characteristic and widespread even today when one has to leave Patmos: perhaps, a resurrection of the flesh with a body now a hundred years old (unlike the Endimions and Actaeons and Adoni who died young and romantic and neo-classical and splendid), and a future all in the company of other old saints and saints who are no fun at all (Jerome, Anthony, Thomas), in an afterlife where the best Gregorian will perhaps already have been abolished as in the hereafter, replaced by the San Remo outtakes performed by Rag. Brambilla on the electric conciliar guitar, with rhymes in “are ”and in “ato”...And if the Tristan and Pélleas la Carmen at the Teatro Regio were not heard, that’s it, it’s over: and to think that it was there just a stone’s throw away from St. John the Evangelist...

“How to make them fly?” was a theme that typically troubled Carlo Emilio Gadda, both because of the technical, engineering, Leonardesque aspects of human flight (cone without dome), and because of the psychological implications that led him to identify with the intimate problems of mythical beings: will the Hippogryph really be happy? won’t the Sphinx be bored, always there alone? what will the Chimera think, all day long? what will he feel, the centaur Chiron, every time the little Achilles jumps on his scantily clad back?... Questions suspended in midair even in this dome where all the onlookers behave as if in a very civilized and well-attended sauna or hammam... if it were not for all those gangs of little boys there between their legs asking and demanding...And if you look up as you do when you exclaim “Juste Ciel!” on the beach in Copacabana, amidst the demands for cigarettes and change, you might attempt some Leonardesque musings -- interspersed with “watch your bag!”, “where’s my costume?”, “leave those shoes alone!”-remembering Gadda exclaiming “such aesthetic grossièreté cannot be allowed to pass!” about “Alfieri’s flight” in Carducci’sOde to Piedmont , where the verses are alas thus: “There came that great one, like the great bird / whence he was named;and to the humble country / above flying, tawny, restless / Italy, Italy / he cried to the meek ears...”

“A problem arises here that the poet did not ask himself, whereas he would have been bound to ask it,” Gadda observed. “How did the great Alfieri fly? And will this Alfieri flying have been so exciting to watch for those who saw him pass over? First of all, an individual flying above us gives us the feeling that he might drop something dangerous on our heads: what do I know, a rock, a bomb. Also, in what toilet does Alfieri fly, according to Carducci? Into that of Icarus? And what spectacle would he then offer to those looking up from below? What if he flew instead in the clothes of his time, not tawny but bald as a knee having contracted ringworm as a young man in the military school of cadets?... In either hypothesis, flying people is always dangerous, and can blossom into impoetic situations par excellence: grotesque-baroque; indeed, of the grotesque-grullo type.”

.. Perhaps here is a very faint (and removed) “souppon” of Carducci and d’Alfieri, in the Correggesque Christ seen from the side of the chorus, with the Italian fear that just down could begin a “Qui freno al corso, a cui tua man mi ha spinto, omnipossente Iddio, tu vuoi ch’io ponga?” (Verses of the Astigian)... And go on perhaps for a long time... But if, in addition to the “ascending” view from the nave and the “descending” view from the choir, one also contemplates this Christ laterally, from the transept, anything but a figure à double face: structure and gestures appear quite polymorphous (even from illustrious Rats of Europe, as if the unwinding figure had been paraded with the bull below), within the luminous contour or dessert d’angiolini more elegant and discreet than in the dome of the cathedral, where a large suction pulls up everything, even a smoothie of Ganymede akin to the Viennese one.

Underneath, however, according to legend, the ambiguous old men would be on Patmos, an island so pleasantly frequented on vacation. And among the many artists who have treated the theme of the visions of St. John in that gem of the Dodecanese with the “magic” hall as Ascona and St-Moritz, even today, some as early as the Renaissance “got it right” visionarily the panorama (like Kafka who guessed America without having been there), so that sometimes at the Metropolitan or the Louvre one meets a small group still tanned that “recognizes” the house of Grace and Joseph, Teddy’s, etc. And not so long ago, either, in the summer, there were greetings on the patmiotee beaches at the monastery of St. John the Evangelist from several old geezers who looked very much like those in the Parma dome - mostly, antiquarian art dealers from London and New York - with wipes and chintilles identical to the Correggesque ones, and just as many little boys willing for a few bucks to bring them back in palanquins his Kora for Byzantine monk services. There was also on those not-yet-mass shores an apostle younger and clearer than the others, but he was the first (perhaps) to leave: he was Bruce Chatwin.

Of course, there had always been the legend of Capri before, as a “topos” of relaxation among mature grandparents and mischievous grandchildren, perhaps (the more elders) busy with towels to cover each other and not show the ugliness to the less-than-shameless teenagers as dinners have always been in droves, always there to sneak in and ask, even on prode and river and stream banks in poor Po Valley Italy. And Roberto Longhi amusedly quotes John Addington Symonds for whom the Correggesque dome of the Duomo would appear to be “a Muslim erotic paradise” with “angels and ephebes such as urses.” He then comments, regarding his colleagues incapable of “epicurean” or “anti-transcendental” interpretations and “enlightened frame of mind,” “but what to expect from a terrain where always luxuriated the forest of eternal Italian arcadia, albeit draped in the costumes of late Romanticism?” He would have chuckled quite a bit upon finding in Symonds’ own Memoirs that his favorite spot in Venice was the little garden of the Fighetti tavern on the Lido, “favored by the gondoliers because Fighetti, a muscular giant, is a hero to them.’ (”In trace of some anonymous Correggesque Giants and Fighetti.“ What a title for a contribution to be sent to anonymous ”Paragons"... But The Memoirs of J.A. Symonds, edited by Phyllis Grosskurth, came out from Random Housea New York only in 1984.)

While we are having fun down here, however, “... Ah, organizing and illuminating a dome!”, Mantegna and Goya inside the largest dome of all must be saying to each other. And they will immediately cite this Johannine masterpiece by Correggio for the sovereign freedom and ease of affections and gestures, Parmesan tenderness and tickling even down among bulls and winged lions in the odor of symbolic evangelism...And not already graceful Delikatessen of historical conjuncture or geographic peculiarity, but inspiration and vocation for a warm and confidential beauty and capable of grandeur as well as intimacy, in a quiver of golden vibrations that create and emanate light (and will the Rococo be perhaps “spillover” or “induced”?...).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.