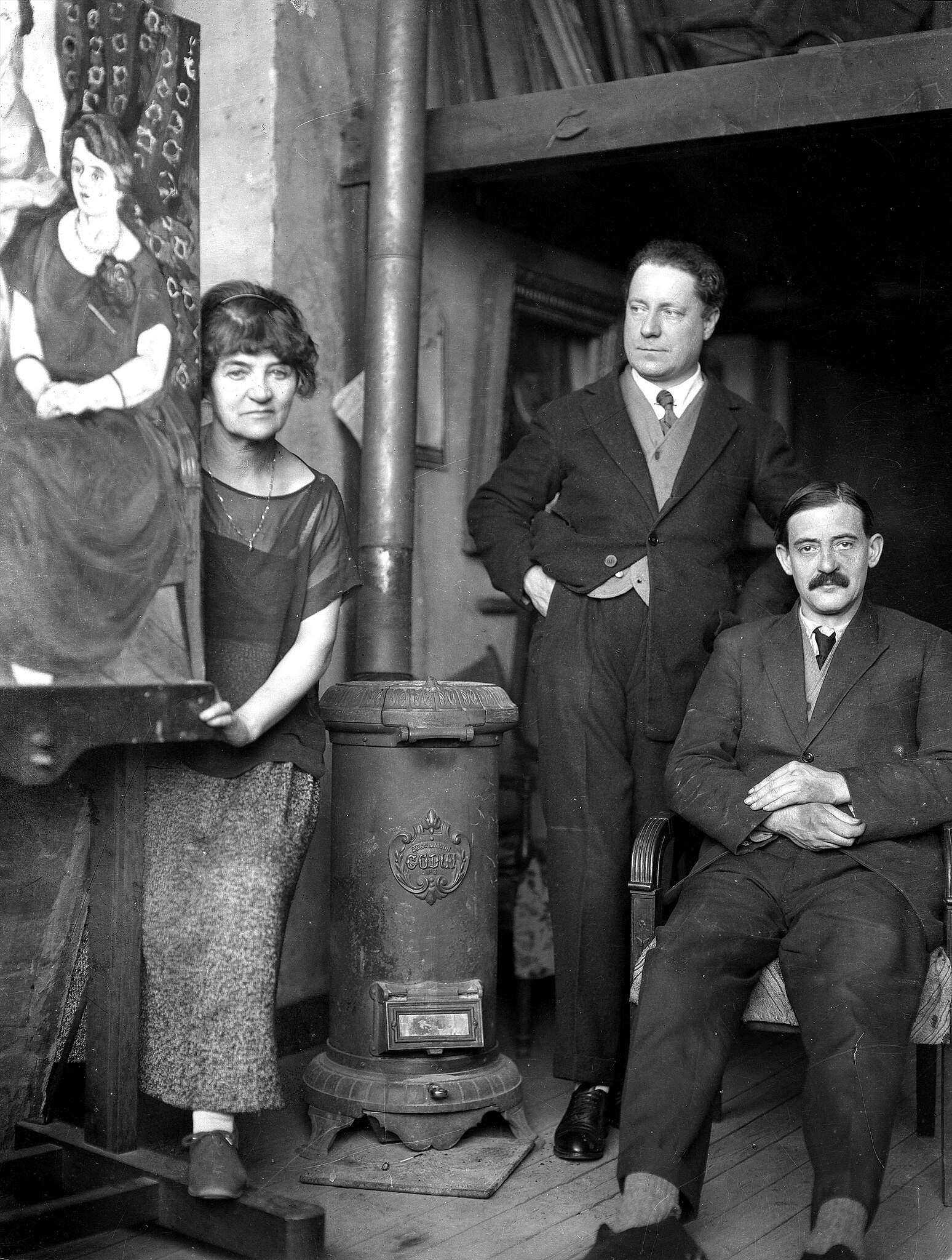

In Montmartre, inside the apartment where Suzanne Valadon, the painter of the infernal trio lived.

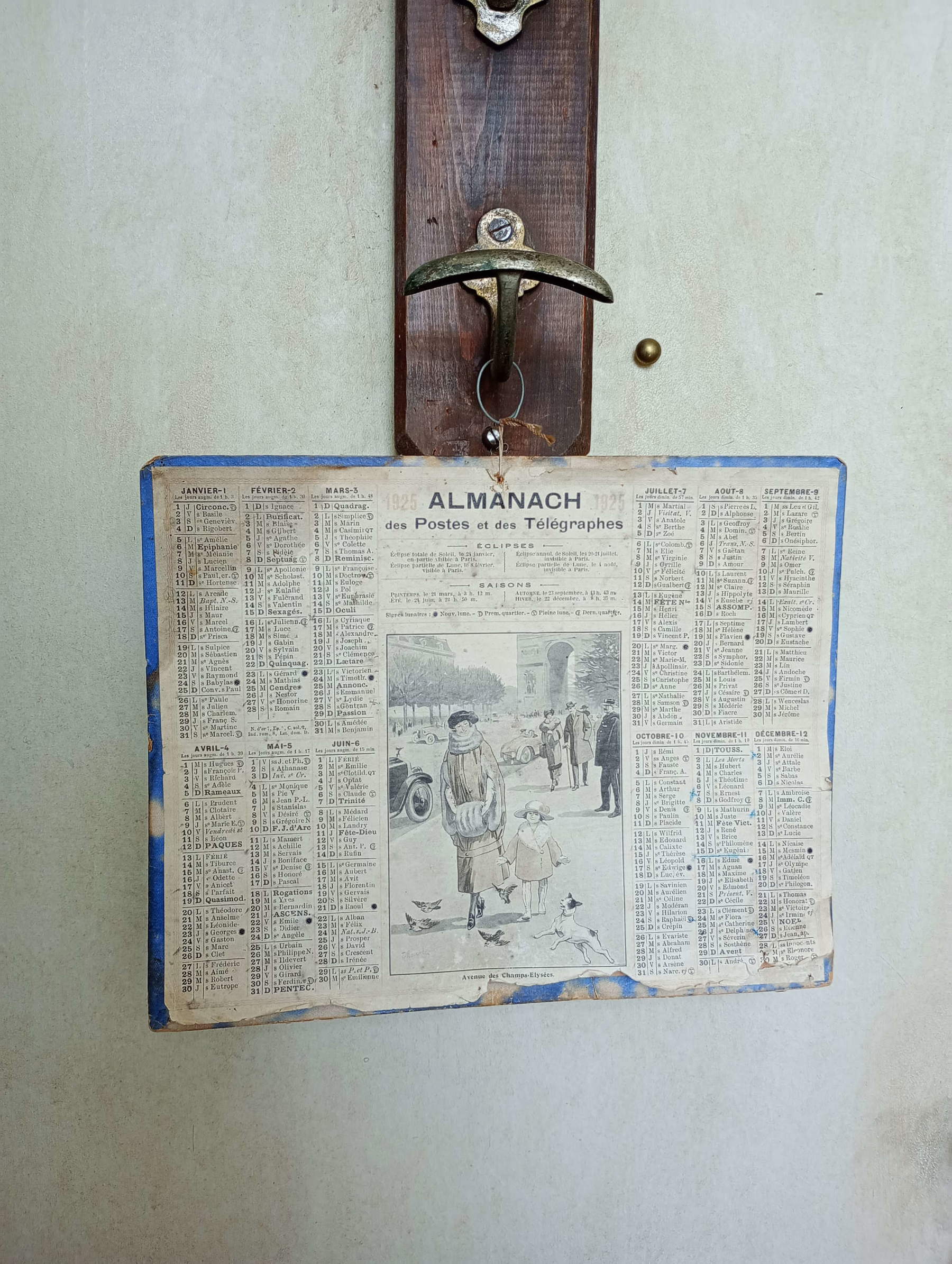

On the second floor of the Musée de Montmartre, a museum I recently visited during a stay in Paris almost by chance, since it is not (fortunately or unfortunately) on the usual tourist circuits of the French capital, I had a pleasant surprise: I suddenly found myself, after walking through the rooms of the temporary exhibition that was in progress, in a brightly lit room characterized by large windows that occupied an entire wall, from which a crazy light came in and was so bright that it flooded the whole room, and from which the surrounding landscape of rooftops and a lovely garden with pergolas, roses and other lush plants interspersed with lantern street lamps was visible. The room is furnished to an artist’s, or rather, painter’s atelier: under the large windows a large work table on which are cases with paints, containers with brushes, palettes, as if the artist had momentarily left his studio only to return at any moment; in one corner an empty easel with stacked paintings next to it, in the opposite corner a closet, and then more frames, paintings, more easels, palettes, chairs, stools, a sofa, furniture, fabrics, even a stove.... a room that thus still seems to be “inhabited,” lived in, to which it seems someone must return within a short time. But the surprises did not end there, for the atelier is joined by other rooms, such as the bedroom, all finely furnished without omitting any detail.

In fact, both the atelier and the rooms of the apartment on the second floor of 12 Rue Cortot, where the Musée de Montmartre is located, are a faithful reconstruction of theatelier-apartment where the painter Suzanne Valadon lived for several years, starting in 1912, with her son and her second husband. Unfortunately, there is not much left of the original, but thanks to the Kléber Rossillon company and the latter’s renovation by designer Hubert Le Gall, who has worked as a set designer with major French museums such as the Muséand d’Orsay, the Musée de l’Orangerie and the Musée Jacquemart-André, the rooms in which the “hellish trio” (as the family was called) lived have been recreated, thus still giving visitors the opportunity to immerse themselves in their world: Le Gall went to unearth all the pieces of furniture currently present and placed them as faithfully as possible to what the atelier-apartment looked like when Suzanne Valadon, son and husband worked and lived here, based on various historical documents such as old photographs, letters and writings of the time. During the twentieth century, successive inhabitants had transformed the apartment, leaving only the structure, but as a result of the redevelopment of the rooms and the designer’s research work, this place has regained its essence, recounting part of the life of one of the early twentieth-century painters who is not as well known as she deserves to be.

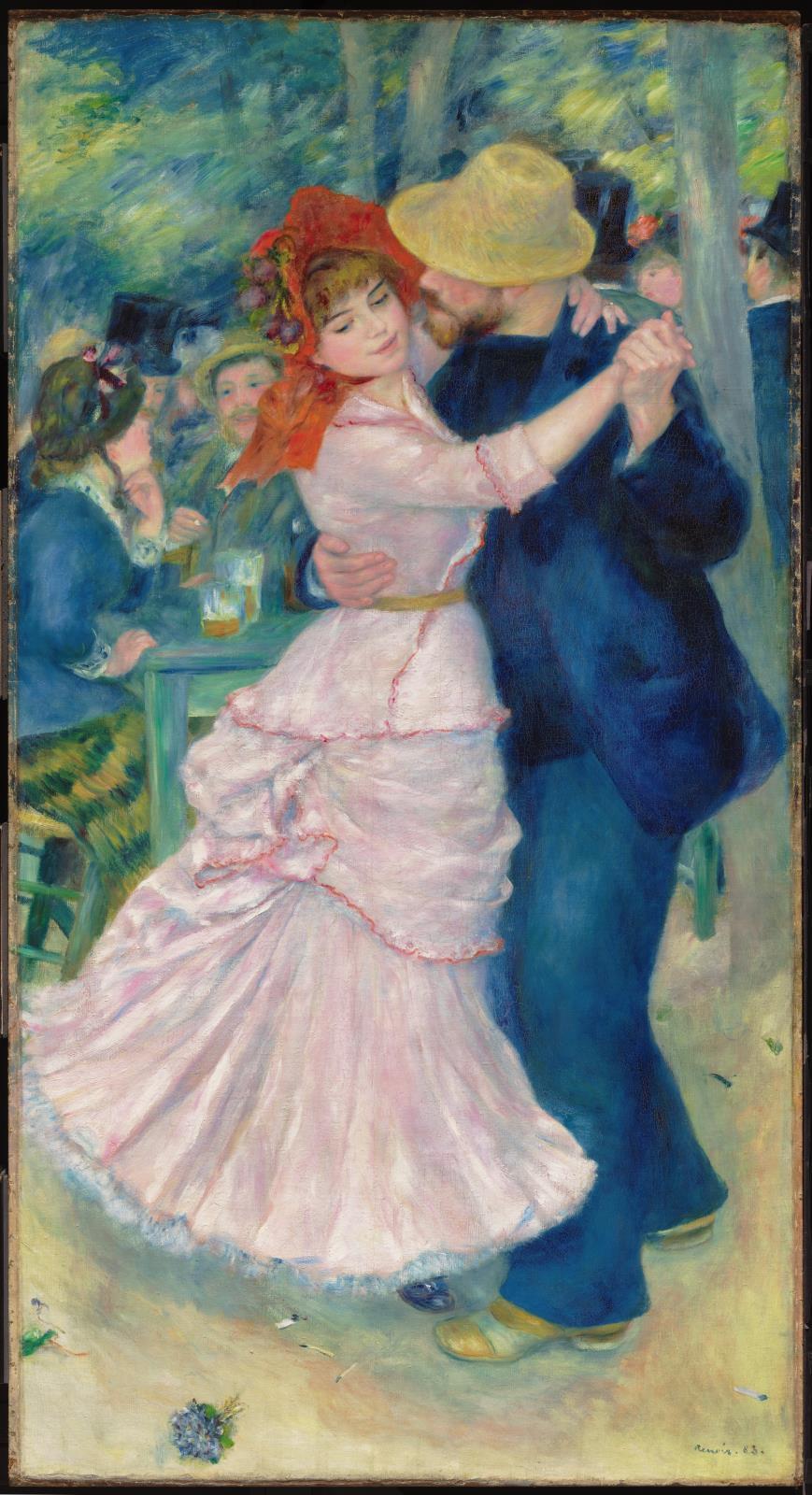

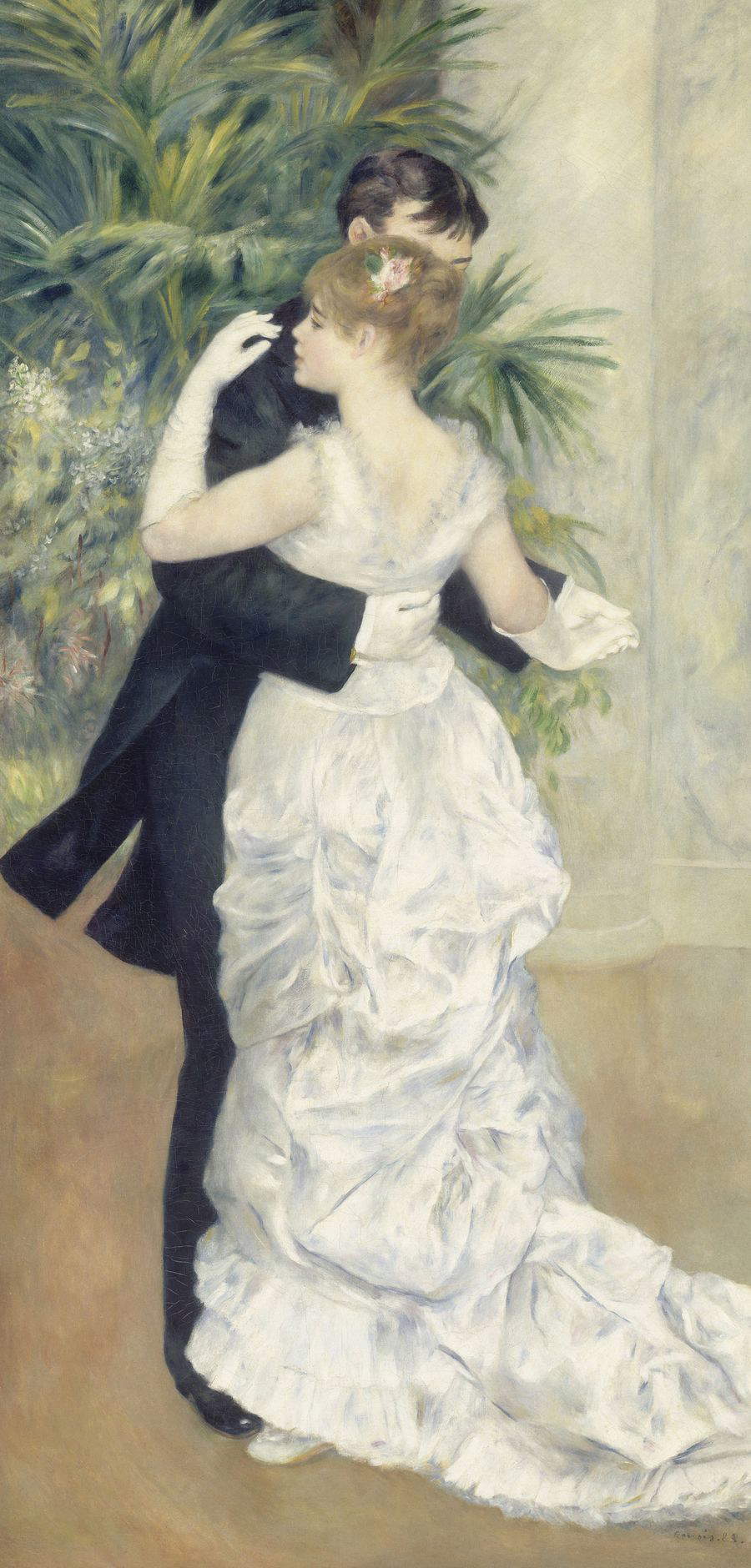

Suzanne Valadon, whose real name is Marie-Clémentine Valadon (Bessines sur Gartempe, 1865 - Paris, 1938), was the daughter of an unknown father and a seamstress mother. After moving to Paris with her mother, Marie-Clémentine began working in a circus as an acrobat until, due to a bad fall, she was forced to leave that magical world for which she was physically suited, as she was agile and slender, and which also gave her a certain satisfaction. But if her body betrayed her, she had no choice but to rely on her good looks and the gracefulness of her face. In the French capital, which teemed with artists, she approached the artistic universe: she met some of the greatest artists of the time and became their model, as well as their lover, it is said. She posed for Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, for Federico Zandomeneghi, she is the young woman combing her hair in one of Pierre-Auguste Renoir ’s works, and again the French Impressionist painter portrayed her in his dancing couples, namely in the Ball at Bougival and the Ball in the City. She is also the woman sitting alone at a café table, in front of a half-empty bottle and glass, in Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec ’s painting titled Gueule de bois, which can be translated as “The Hangover”: the young woman has her gaze fixed in the void, is leaning with her elbows on the table and with one hand holds her chin. It was Toulouse-Lautrec himself who gave her the nickname Suzanne, the name by which Valadon is still known today, in reference to the biblical episode narrated in the Old Testament, Susanna and the Old Men, as often modeled for painters older than her (with Renoir and Zandomeneghi she was actually almost twenty-five years apart, with Pierre Puvis de Chavannes more than forty, while Toulouse-Lautrec was older than her by only one year). But while she was posing as a model for these artists, Valadon was also able to approach painting and drawing as an artist, observing them and picking up from them the basics and techniques of the craft, thus indirectly transforming her posing sessions into lessons that were useful to her from a practical point of view. Without ever officially being a student of them, however.

The turning point came when Edgar Degas, thirty years her senior, saw some of her drawings and was pleasantly impressed, recognizing her artistic talent, so much so that in a letter he wrote “Cette diablesse de Maria a le génie pour ça,” referring to some of Valadon’s sanguine drawings. Degas always called her Maria, the nickname she gave herself when she modeled for artists before being nicknamed Suzanne; “diablesse,” or the terrible one, referred instead to her temperament, assertive and exuberant. She never posed for Degas, but became his pupil, and he supported and endorsed her artistically (he was also one of his most important collectors), and openly declared that “she was one of them,” a true artist. In fact, the French painter was not wrong: in 1894 Suzanne Valadon exhibited for the first time in a Salon, in the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, together with Camille Claudel, and then she exhibited regularly at the Salon des Independents, at Berthe Weill’s, which supported modern women artists, and at the Salon d’Automne, of which she became a member in 1920.

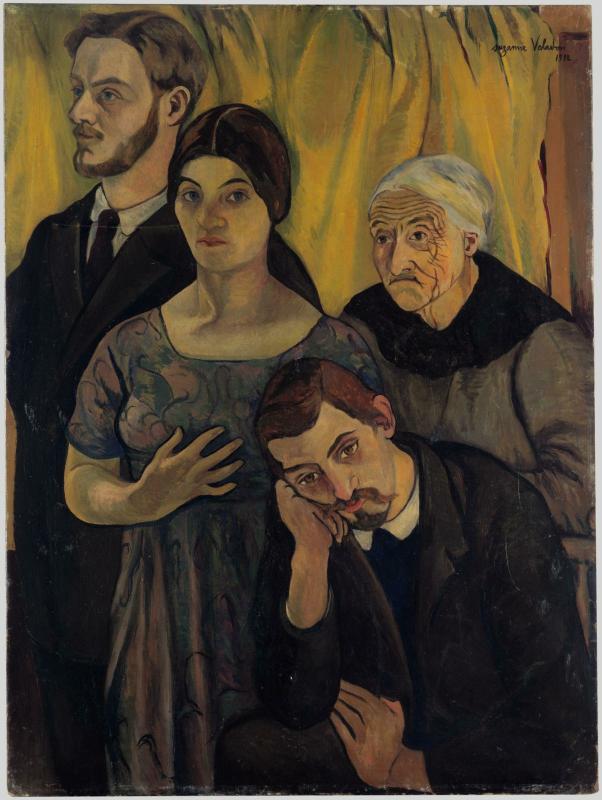

Meanwhile, in 1883, at the age of eighteen, she became pregnant and that same year gave birth to her son Maurice, who was legally recognized some time later by Spanish painter Miquel Utrillo , who was dating the girl at the time of conception. The child, the future painter Maurice Utrillo, was substantially raised by his grandmother Madelaine, Marie-Clémentine’s mother: this is why in several paintings and drawings the grandmother is also depicted either next to Maurice or in family portraits, as in the 1912 one preserved at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. In 1896 Valadon married wealthy stockbroker Paul Mousis, a friend of Erik Satie, a French composer and pianist with whom she had an affair, and two years later the couple with Maurice went to live at 12 Rue Cortot in Montmartre until 1905. But things were not going well between the two, so that eventually the couple decided to separate. A new love for Suzanne would come very soon, however: she fell in love with a friend of her son Maurice, André Utter, twenty-one years her junior and a painter. The three, who, as mentioned above, received the nickname the “infernal trio” of Montmartre because of their turbulence, settled in the studio-apartment on Rue Cortot, the one that can be seen reconstructed today at the Musée de Montmartre: Suzanne then returned with another man to the civic house where she had lived with her first husband; the same civic house where Pierre-Auguste Renoir had also lived in 1875-1876, and in whose garden La balançoire and Bal du moulin de la Galette had been made, masterpieces both now housed at the Musée d’Orsay.

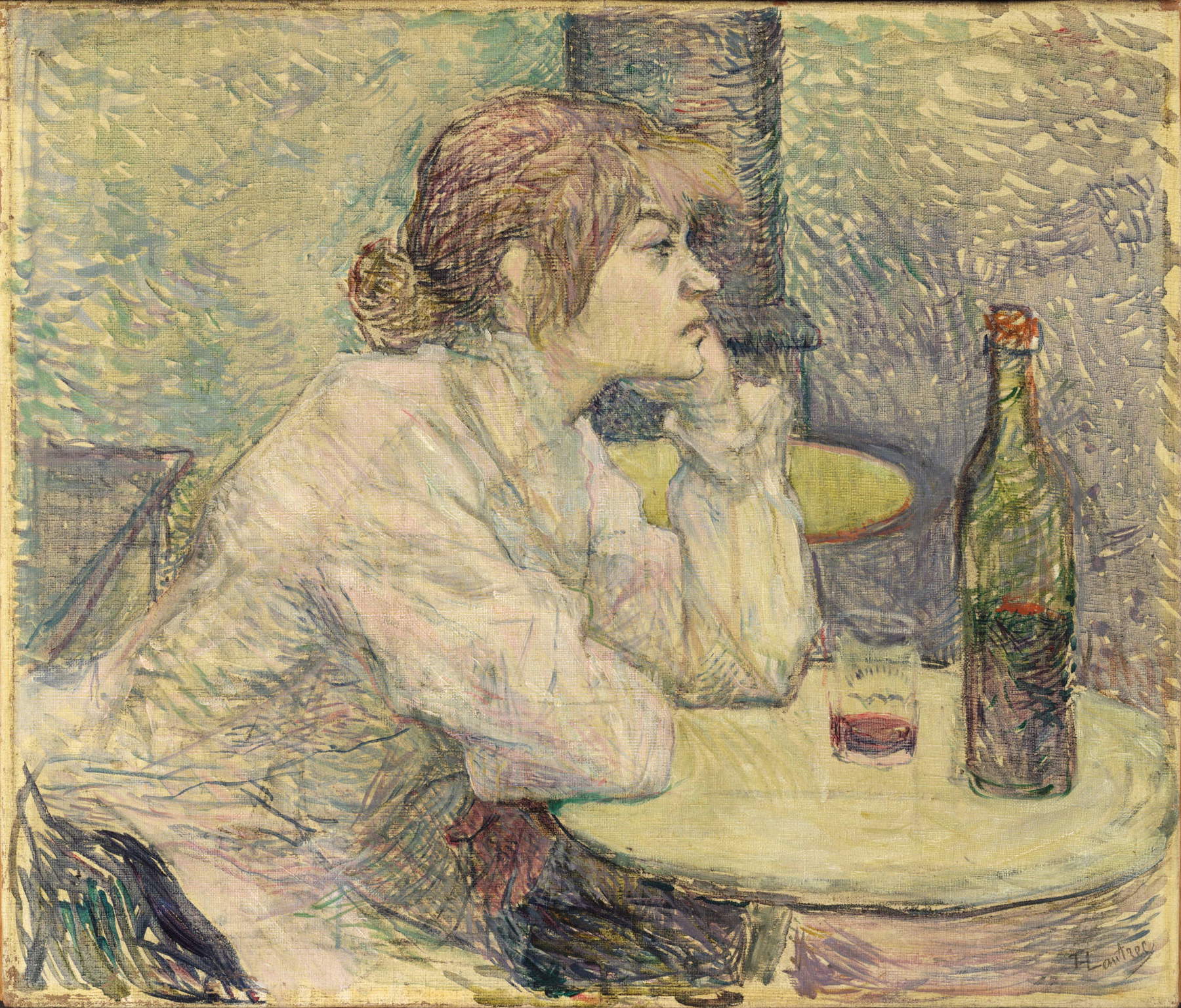

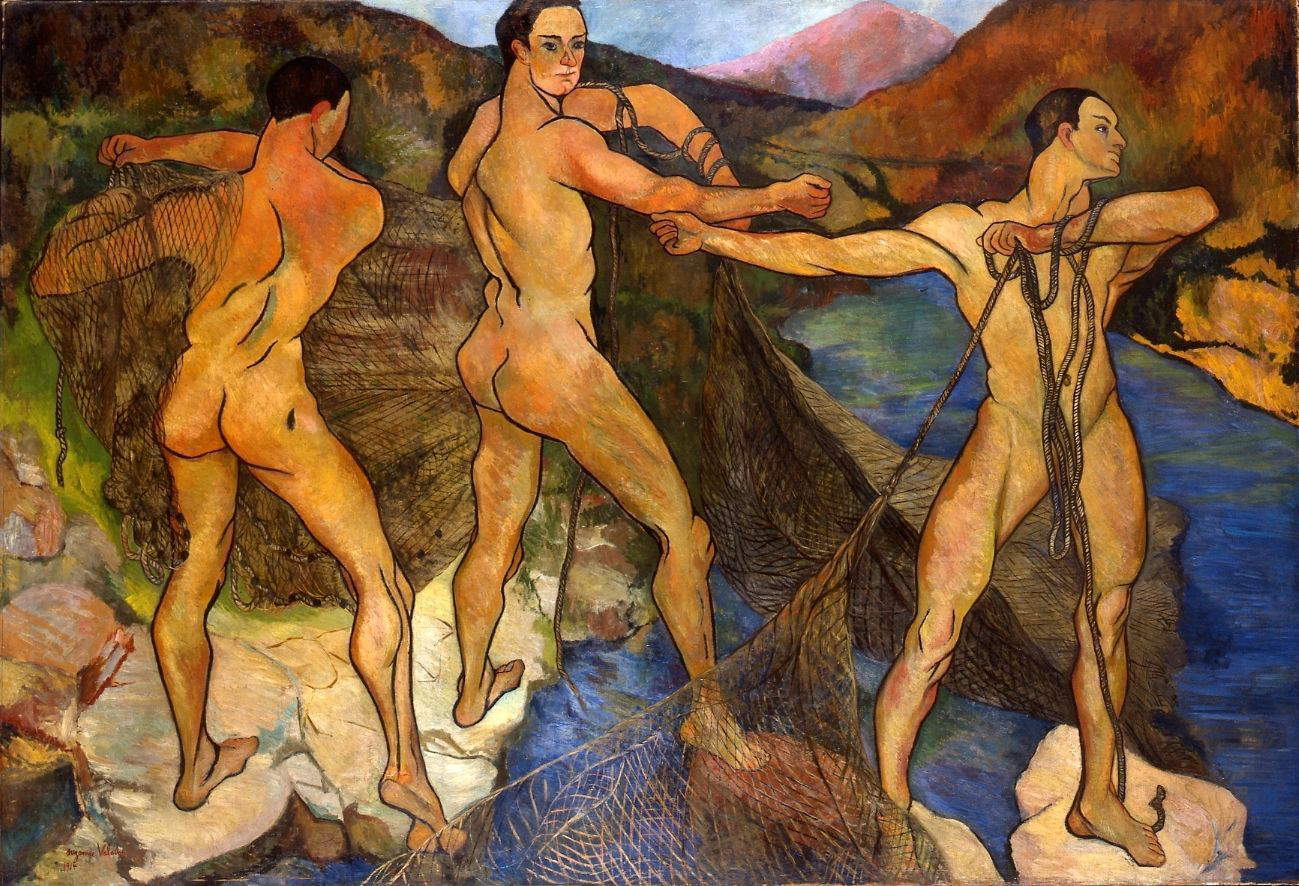

Suzanne, Maurice and André stayed here from 1912 to 1925. Valadon and Utter’s union lasted about thirty years; they married in 1914, and Utter’s athletic body inspired at least two works for the painter: Adam and Eve, from 1909, in which the first man and woman depicted naked under an apple tree in the act of plucking the fruit of sin from the tree would be portraits of the artist and the young man; The Throwing of the Net, from 1914, in which the man’s naked body is depicted in three different poses, as a kind of study of the body depicted in three sequences of the same gesture side by side. The painting was presented that same year at the Salon des Indépendants raising not a few criticisms because of the bold choice to emphasize the athletic beauty of the male body with a certain amount of eroticism. Adam and Eve was instead presented in 1920 at the Salon d’Automne, but an analysis of the work revealed that the vine leaves on the man’s private parts were added later in a repainting. Probably an act of censorship toward a very modern artist who had frontally painted a completely naked male body, the object of her desire, next to her own naked body.

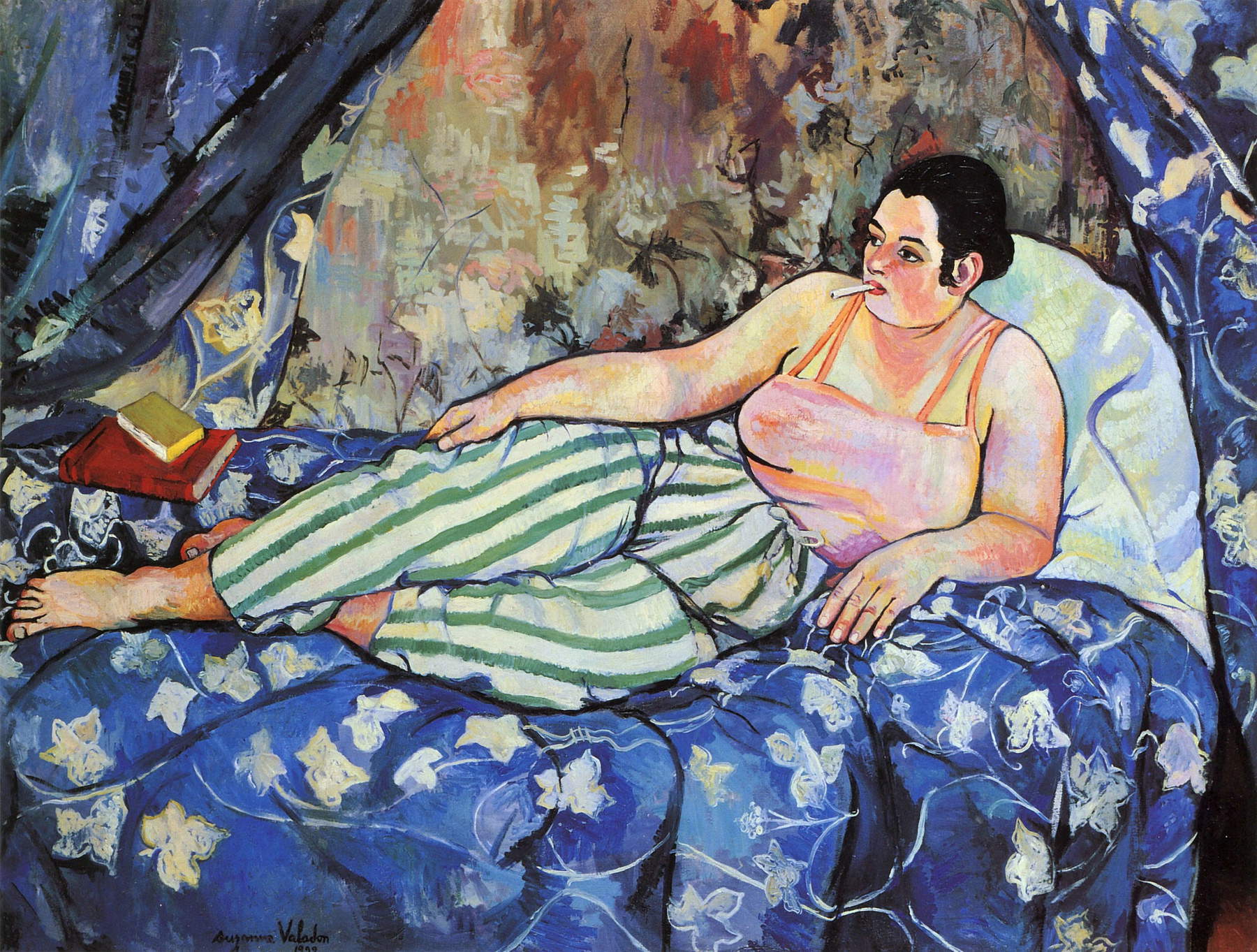

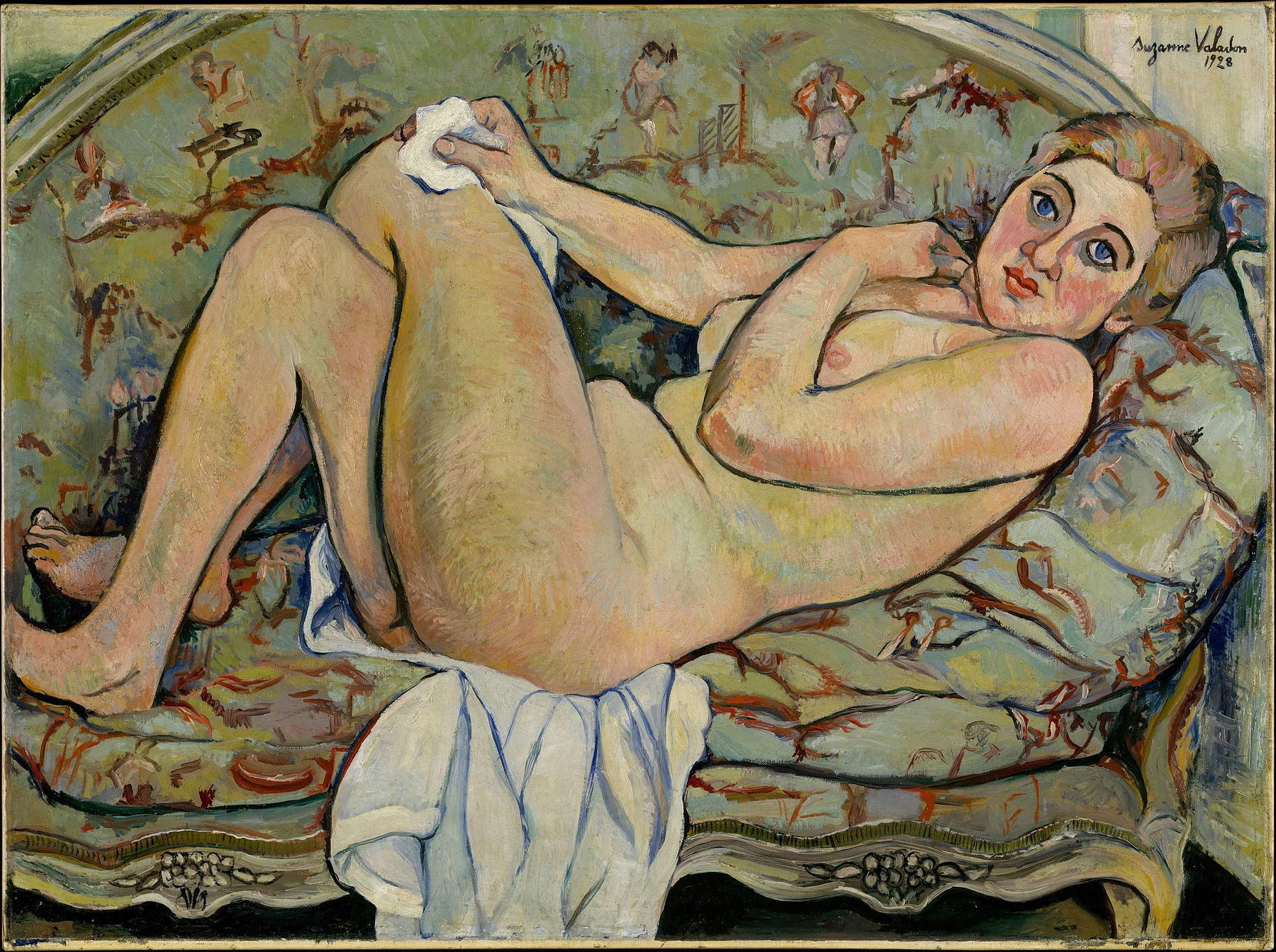

Suzanne Valadon was for her time a modern painter who tended to go against the conventions of the time: another very significant example is The Blue Room, her 1923 work now in the Musée des Beaux Arts de Limoges, which depicts a woman portrayed in a relaxed pose, leaning on her side, on a bed with blue sheets: she does not look toward the viewer and therefore does not provoke with languid glances (in contrast to the protagonist of her 1928 Lying Nude preserved at the Metropolitan Museum in New York), she wears a sort of pajama top and wide striped pants, holds a cigarette in her mouth and books resting on the bed. A painting that appears to be a reimagining of one of the much cherished and provocative odalisques of which male-sided nineteenth-century art is full, Suzanne reinvents into a modern, clothed, smoking, reading Olympia, depicting a woman who goes beyond stereotypes of submission to men and society.

His such modern art, which also earned him membership in the Société des femmes artistes modernes, would nevertheless end up being somewhat overshadowed by that of his son Maurice, who came to painting thanks to his mother, on the advice of a neurologist, in order to overcome his problems with alcoholism and character disorders that often led him to irascible episodes. It was also through painting that his mother had the opportunity to recover her relationship with her son, after a childhood spent mainly with his grandmother and after his hospitalization in a clinic in the psychiatric ward: the two reached a strong bond, supporting and protecting each other. Maurice specialized in depicting cityscapes, often including Montmartre, in a style closer to Impressionism. He thus began to sell more paintings than his mother, whose style was markedly different, inspired by Matisse, Cézanne, and Gauguin; he married an older widow who took clear control of the painter’s business and sales, ending, at least in Suzanne’s eyes, the close mother-son relationship.

Suzanne Valadon’s life passed away due to a stroke in 1938, leaving behind some five hundred canvases and three hundred works on paper. Of the hellish trio who lived and worked at 12 Rue Cortot, Maurice Utrillo is the painter who is most celebrated today. And Suzanne Valadon? Let us not just refer to her as “Maurice Utrillo’s mother,” but as one of the most modern artists of the time.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.