In Lucca, among the splendors of Palazzo Mansi and its National Museum.

He had been to Lucca, the father of American realist literature. William Dean Howells had arrived in Lucca one day in April, leaving from Pisa under a sun that already at eight o’clock in the morning seemed hot and sickening, he who was used to the cold of New England and was dismayed to think what it would be like to see Tuscany in August. He had taken lodging at the Universe (or perhaps at another hotel, he could not remember) and the next day he had immediately plunged into the ancient alleys of Lucca, to breathe the air of the city that had been the capital of an independent republic for almost a thousand years, able to keep its ancient freedoms intact until the time of the French Revolution. Piazza Napoleone had not seemed much to him: “a vast dusty square, with a few sycamores that had been retouched, and a huge, ugly palace with only a discreet gallery of paintings, in front of the dust and sycamores.” Medieval Lucca had impressed him more than ducal Lucca: the Cathedral, San Frediano, San Michele in Foro, the archaeological collection that was inside Palazzo Pretorio, the Guinigi tower, Piazza Anfiteatro and the market with stalls selling silk (“there is a lot more silk in Lucca than in Boston”), the oil of Lucca, the walls. And then Palazzo Mansi, the only Lucca palace that Howells had managed to see properly. His account of his visit to the city ended precisely with Palazzo Mansi. And Howells said he was glad “to be a commoner and to be an American,” but if he had been backed into a corner, if someone perhaps had presented him with another option, then he would have liked to be “a lord of Lucca, a marquis, a Mansi.”

From the outside, it is not easy to notice Palazzo Mansi. It is the first in a series of buildings that, one after the other, follow one another along Via Galli Tassi, a somber street, not very busy and not even very central. It is austere, there are no special decorative elements, the appearance is almost resigned. However, the entrance is a little wider than that of the other palaces, and if you pay attention to it, just take a few steps back, you will notice a body of the building with dimensions decidedly more imposing than those of the other palaces, the molded windows succeeding one another with balanced regularity, the stringcourses running all along the facade and already from the outside suggesting the height of the ceilings of the rooms. And indeed, all travelers who lingered at Palazzo Mansi could not help but notice the disagreement between the sobriety of what is seen outside and the splendor of what is inside. A magnificent palace. The home of one of Lucca’s richest families. It was like this in the early twentieth century, when Howells was writing. It was like this in the seventeenth century, when the Mansi bought this palace and then, at the end of the century, renovated it by amalgamating several neighboring houses and turning it into a sumptuous residence. That is how it is today, although of the splendid collection that once adorned these rooms today almost nothing remains. Gone are almost all the Mansi paintings. Gone are the Mansi family, who sold their palace to the state in 1965. Gone in silence is the Salone della Musica, where we can imagine the parties, the receptions, the Mansi welcoming their guests while the orchestra plays from the wooden box warming up the evenings of the nobility who convened here, especially when it was their turn to revere some illustrious personality who had come to stay in the rooms of the palace. There remains, however, a sense of the prosperity that has always been the mark of Lucca over the centuries and that is reflected here inside, among the stuccoes of the parade apartment, under the frescoes celebrating the status of the family, in the midst of Giovan Gioseffo del Sole’s Aeneid that covers all the walls of the spectacular Salone della Musica. And today, every now and then, when the National Museum of Palazzo Mansi holds musical afternoons, that Salone resounds for a different audience. No longer for friends of the Mansi: for everyone.

Howells had been impressed by Marquis Mansi’s rich collection of Dutch paintings; it was the first thing he jotted down in his account of the palace. These were the works that an ancestor of the family, Girolamo Parensi, had received as a dowry in 1675 by marrying Anna Maria Van Diemen, the daughter of a Dutch merchant whom Girolamo had met during a long business stay in Amsterdam: their portraits are still here, on the first floor of the palace. The Parensi family was the head of a company active in the textile trade, their silks traveled all over Europe, they were one of the most solid pillars of their wealth. They had an import-export business, we would say today. The Mansi family, who by marriage inherited the Parensi collection in the early 19th century, also worked in textiles, they too were merchants. The family’s vocation is still kept alive today by the “Maria Niemack” Rustic Weaving Workshop, installed on the first floor of Palazzo Mansi: it is dedicated to the businesswoman who, in the mid-20th century, recovered the technique of rustic weaving and who, when she passed away in 1975, wanted to donate the looms to the National Museum of Palazzo Mansi. And for some time now a volunteer association, “Tessiture Lucchesi,” which aims to give value to traditional hand weaving, has been putting those looms back in motion. Thus a small, valuable production of scarves, shawls, dishcloths and so on is coming out of Palazzo Mansi.

Of the Dutch collection inherited by the Mansi family (indeed: of the collection in general), however, almost nothing remains. Little survives: the most important painting is a Sacrifice of Isaac by Ferdinand Bol hanging in one of the two antechambers of the private apartments. The large picture gallery one encounters past the Salone della Musica has nothing to do with the Mansi: these are the paintings that were donated to the city in 1847 by Leopold II of Lorraine after Lucca was annexed to the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. The last Duke of Lucca, Carlo Ludovico di Borbone, had sold off most of the collections to repay the debts he had accumulated. At ridiculous prices, moreover. And one of the city’s most distinguished neoclassical painters, Michele Ridolfi, after the annexation asked the grand duke to fill that gap that had mortified the Lucca community. Leopold II showed himself magnanimous and gave Lucca eighty-two paintings: they were displayed in the Ducal Palace and remained there until 1977, when the Pinacoteca was moved to Palazzo Mansi, after the state purchased the building. If, then, today in the picture gallery of the Palace we can admire masterpieces by Pontormo, Salvator Rosa, Domenico Beccafumi, Guido Reni, Tintoretto, Luca Giordano, Jacopo Vignali, Paul Bril and other greats in the history of art, well, this is the result of a complex sequence of historical events that were not always happy for the city. It is a wound healed.

Even the Mansi family, however, had not been very careful with their collection. The family’s collection over time was dismembered. What can be seen in the historic rooms today is the result of subsequent donations and purchases: these are works that serve to offer visitors the suggestion of what a guest of the Mansi could see here in ancient times. It must be said that the National Museums of Lucca have made a commendable effort to acquire paintings for the collection, according to a precise enrichment program studied and followed since the 1980s. Under the past direction of Maria Teresa Filieri, works arrived that sought to mend as much as possible that which had been torn away, bringing back to the palace even works that had once been in the Mansi collection: in 2008, for example, two canvases by Mario Nuzzi were purchased that were part of a series of eleven paintings depicting as many flower boxes, the genre in which the Roman painter specialized, who was nicknamed “Mario dei Fiori” because of this peculiarity. Important evidence of the Mansi’s wealth, since Nuzzi was one of the most sought-after and highest-paid painters of his time, and only a wealthy family could afford his work. Then two years later came one of the collection’s masterpieces, Stefano Tofanelli’s sketch on canvas for the Chariot of the Sun that adorns the central hall of the Villa Mansi in Segromigno, not far from Lucca (it is to Tofanelli, moreover, that we owe the splendid Galleria degli Specchi in the Palazzo Mansi, the elegant neoclassical room that welcomes visitors to the piano nobile). The work added to the section of the picture gallery, located on the second floor of the Palazzo Mansi, which documents the arts in Lucca between the late 18th century and the mid-20th century, offering visitors a vital insight into how taste in the city changed during this time, what patrons ordered, and above all how vibrant the local art school always was, even over such a long period.

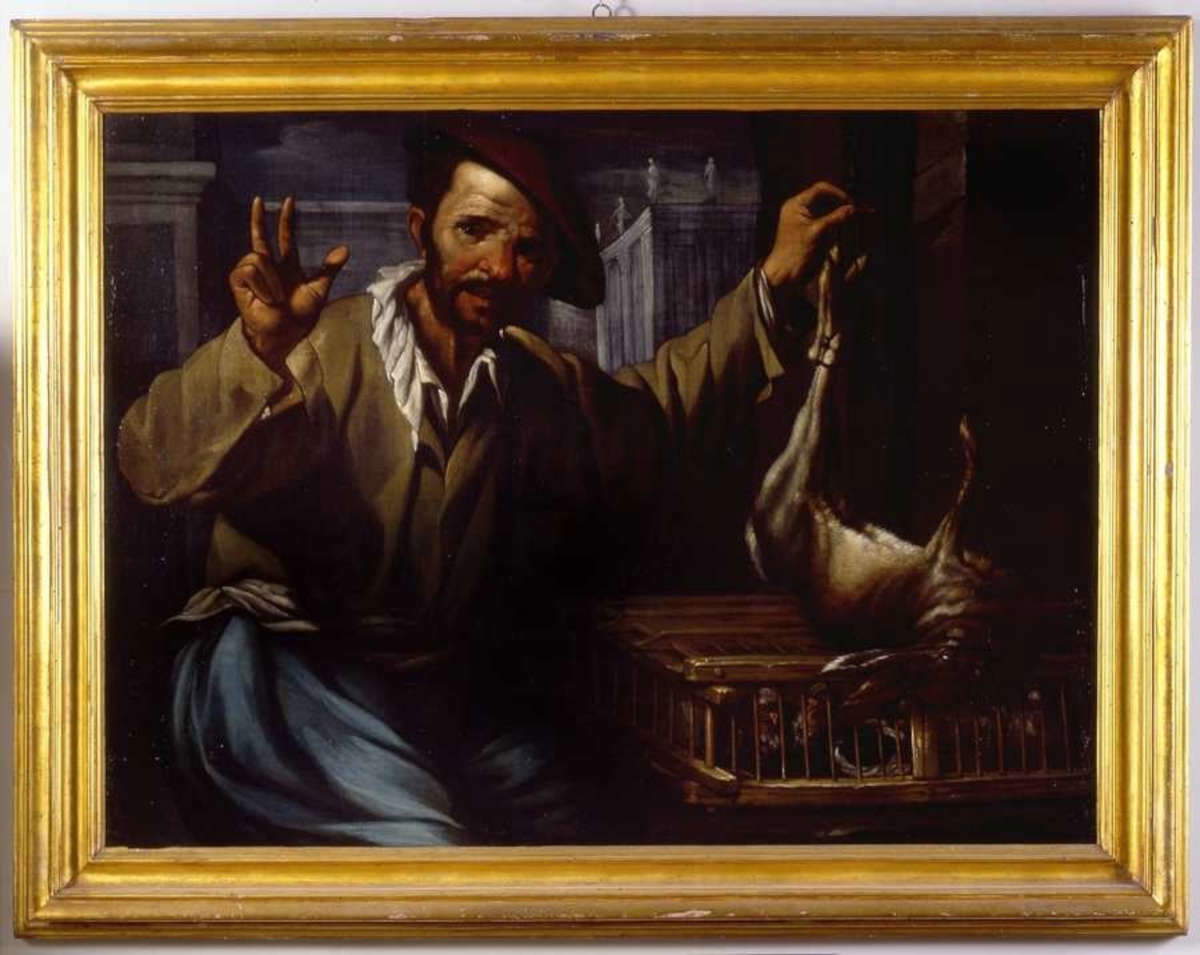

In the past, the Mansi collection must have been something fabulous. Another traveler, the German painter Georg Christoph Martini, had written in 1731 about a visit he made to Palazzo Mansi, not to be understood, however, as the palace on Via Galli Tassi: Martini had been in what is now known as Palazzo Tommasi, next to the church of Santa Maria Forisportam, on the other side of town. At the time it was owned by the Mansi family, and Martini claimed to have seen there, in addition to “precious carpets from Brabant” and “parade cloths which for the feast of Corpus Christi are displayed in the windows,” also “remarkable paintings by Michelangiolo da Caravaggio.” That Martini mentioned Caravaggio should come as no surprise: first, because when the name of the author of a painting was unknown, it was quite common for the work to be casually attributed to a famous artist. The example of Pietro Paolini’s Deposition , which can be admired in the nearby church of San Frediano and which in the past was attributed to Caravaggio himself, is worth mentioning. And then because Merisi, in the 18th century, was not held in high regard. Critics did not give him the attention that they began to devote to him from the 1950s onward, and if something came close to his manner it did not seem so strange to assign it to him. And in any case, even if the Mansi did not have works by Caravaggio, they did have works by Caravaggesque painters: their inventories record, for example, some works by Pietro Paolini, who was the finest and most original interpreter of Caravaggism in the land of Lucca. Caravaggism that, within the walls of the city, had many followers. Then there were works by Angelo Caroselli, by Dirck van Baburen, by artists who therefore could easily have been equivocated for Caravaggio in a historical period in which there was little care for philological reconstructions. Two of Paolini’s works, moreover, have been acquired in recent times for Palazzo Mansi’s collections: the Mondinaro and the Pollarolo have been hanging in private apartments since 2000.

Next, in the same room that houses Pietro Paolini’s two genre scenes, one can admire a Holy Family that was formerly attributed to Van Dyck: along with Bol’s Sacrifice of Isaac , it is the only surviving work from Anna Maria Van Diemen’s dowry. The painting’s history is rather adventurous: it went missing along with the rest of the Mansi’s collections, was sold at auction in 1970 by the Cenami-Spada family, and on that occasion was purchased by the City of Lucca, which decided to return it to the palace from whence it came. It is a copy of the one by Rubens that is now in the Prado; we do not know who the author is. But above all it is a witness to the Mansi’s collecting taste, and it is a witness to the work that is done in museums to reconstruct contexts, to evoke what has been lost. Besides, this painting must have been held in some esteem in the past: in a popular nineteenth-century English guidebook, Murray’s Handbooks for Travellers, the Holy Family was listed as one of the palace’s highlights. Along with the Flemish tapestries.

These are the ones hanging on the walls of the four parade rooms leading to the alcove, the bedroom where, in cinematic fiction, the Marquis del Grillo slept in the film starring Alberto Sordi. Beneath the frescoes by Giovanni Maria Ciocchi, who in the midst of Marcantonio Chiarini’s quadratures painted the allegories of the four elements, towards the end of the 19th century Marquis Raffaele Mansi Orsetti wanted to arrange that grandiose cycle of’seventeenth-century tapestries illustrating the Stories of Aurelian and Zenobia, also adding a few inconsistent pieces, with the stories of Antony and Cleopatra, identified by the inscription “pars accomoda,” indicating that they had been used to fill in gaps. An ancestor of Raphael, Ottavio Mansi, had bought the tapestries with the stories of Zenobia in Flanders. It is by looking at these tapestries, the work of Geraert Peemans of the Brussels manufactory based on the design of a Rubens pupil, Justus van Egmont, that one arrives at the heart of Palazzo Mansi, at the alcove, which remained as it was when Carlo Mansi, on the occasion of his marriage to Eleonora Pepoli, wanted to transform it into a highly scenic setting, with the serliana designed by thearchitect Raffaele Mazzanti, in carved and gilded wood, the four caryatids leading into the room covered with gilded satin tapestries, where in the center stands out the canopy with branches, blue parrots, parakeets, sparrows, blackbirds, quails, and birds of all kinds perched among the pomegranates, tulips, roses, irises, carnations, and bunches of grapes. It is perhaps this room that is the most striking image of how the Mansi saw themselves, and how they wanted to be seen. So much so that they usually did not use it. They left it for special occasions, or for distinguished guests. The king of Denmark, Frederick IV, for example. Or the Grand Duke Gian Gastone de’ Medici. Princes, dukes and kings who slept on this bed, which must have surprised ancient visitors as it surprises those of today.

Recently, the director of the National Museums of Lucca, Luisa Berretti, had the alcove subjected to a thorough cleaning followed by the consolidation of the fabrics, an operation, conducted by the RTBP company, that made the tarnished golds shine. An intervention that followed that of 2021, when the new lighting system of the seventeenth-century tapestries was inaugurated, created by the firm ZR Light with Erco Illuminazione, with the aim of enhancing the colors, bringing out the details of those cloths that tell the story of the princess of Palmyra. To think they had been a bad buy: Ottavio Mansi had asked one of his agents in Flanders, Ascanio Martini, to buy some tablecloths. And that one, no one knows why, no one knows what he understood, sent him these beautiful tapestries. The marquis then tried to resell them, unsuccessfully. And maybe that was okay.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.