Dosso Dossi had a boundless imagination: his whimsical, versatile, ingenious, imaginative flair is among the most celebrated in the history of art, and few in his era could come close to his visionary imagination. A myth, a literary text, a biblical episode became for Dosso Dossi a source of innumerable cues, suggestions, fantasies that he poured onto his canvases, onto his panels, onto all the products of his extravagant brush. Mauro Lucco described him as a painter endowed with an “ability that has something magical, something witch-like.” A sorcerous painter: we could call this magical artist that. Real name Giovanni Luteri, he was born around 1487, perhaps in Tramuschio, between Mantua and Ferrara, or perhaps in San Giovanni del Dosso, a village at the time known as Dosso Scaffa (hence the name), also on the outskirts of Mantua. Nothing is known about his early years, since the first document about him dates from 1512, and at that chronological height he was already an established artist, able to receive a commission from Marquis Francesco II Gonzaga. As early as the following year, however, he was in Ferrara, a city to which he was closely linked: it was here, at the court of the Este family, that Dosso developed his witch-like flair, it was here that he immersed himself in reading the classics and contemporaries (Ariosto above all), it was here that his brush was imbued with the courtly culture that often makes his paintings appear undecipherable. Sprezzatura translated into images. Works reserved for the few.

His most famous works were born in Ferrara. TheApollo and Melissa in the Galleria Borghese in Rome, the abandoned Psyche, the Aeneid cycle and the “mandola painting” paintings all executed for Alfonso I, theHercules among the Pygmies, perhaps the Circe in the National Gallery in Washington, certainly the Jupiter and Semele that reappeared a few years ago on the market. And the list does not lack the Jupiter painter of butterflies which is among the most relevant paintings of the entire Dossesque production, although little known because it is preserved in a place not so usual for art lovers, namely the Royal Castle of Wawel in Krakow. However, the Italian public has had the opportunity to see it on a few occasions: the exhibition Dosso Dossi. Rinascimenti eccentrici al Castello del Buonconsiglio, held in Trento in 2014 and curated by Vincenzo Farinella, and then the exhibition, also in 2014, on the Este at Venaria Reale curated by Stefano Casciu and Marcello Toffanello, and then, ten years later, the major exhibition Il Cinquecento a Ferrara. Mazzolino, Ortolano, Garofalo, Dosso at the Palazzo dei Diamanti in Ferrara, from October 12, 2024 to February 16, 2025, curated by Vittorio Sgarbi and Michele Danieli.

The painting has been in Poland since 1888, when a Polish collector, Karol Lanckoroński, bought it in the auction of works from the collection of Austrian Daniel Penther, held at the Miethke antiques gallery. For a long time it remained one of the prides of the family collection housed in the Jacquingasse palace in Vienna, where there was a gallery devoted to Italian painting. Like many of the possessions that belonged to the Polish nobility, the Jupiter Butterfly Hunter also suffered the vicissitudes of World War II, although it managed to overcome them unscathed: confiscated by the Nazis at the time of the Anschluss, at the end of the conflict it was found by the Monuments man, like so many other works of art, in the Altaussee mine that had been used as a hiding place for treasures the Nazis had looted during the war. The painting was thus returned in 1947 to the Lanckoroński family: Karol’s son Anton decided to donate the work to the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna in exchange for permission to export part of the family’s collections. However, several years later, an heir, Karolina Lanckorońska, regained ownership of the painting after a trial: a court in fact ruled that Anton’s donation had been coerced. And by the decision of its owner, the painting, following the end of the legal dispute, was donated to the collection of the Wawel Castle. It is because of these long historical vicissitudes that Dosso Dossi’s masterpiece is there today.

The first reliable record dates from 1659, but by that time the work was already far from Ferrara: it was then in Venice, in the collection of Count Widmann. Here it was seen, four years later, by the scholar Giustiniano Martinioni, who, describing the nobleman’s collections, said, “of Dossi is seen a Jupiter, painting Butterflies, with Virtue, asking audience, which is prevented them by Mercury. The Fable is by Luciano, but very well expressed by the painter.” It is quite certain, however, even in the absence of certain documents, that the painting, due mainly to the size and complexity of the subject, was commissioned by Alfonso I d’Este, although we do not know which of the ducal residences it was intended for: perhaps the Delizia del Belvedere, as speculated by Vincenzo Farinella, or the dressing rooms of the Via Coperta, where it would have joined the “9 mandola paintings” that Dosso painted for Alfonso I’s bedroom. The culture that animates this painting, however, is unquestionably Ferrarese.

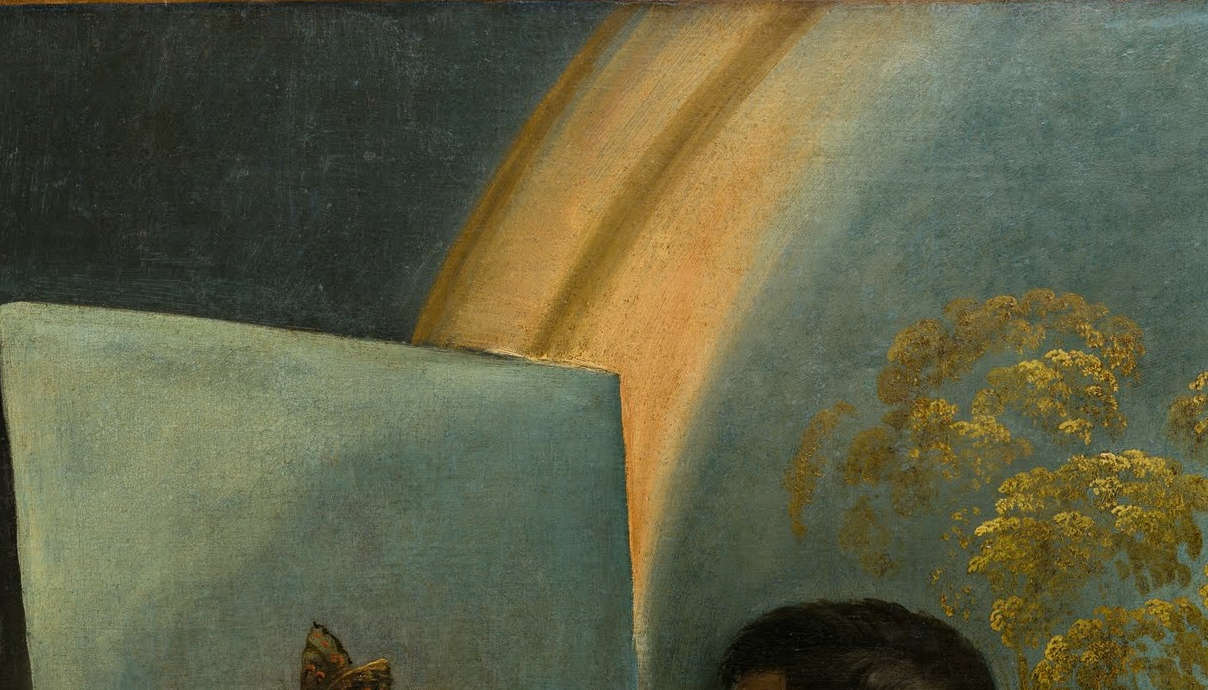

Within a wooded landscape, with a village in the background (it can be seen in the bottom right), Jupiter, on the left, is intent on painting some butterflies on a canvas that has already been fixed to the easel and already prepared. He is painting casually, confidently: his legs, barely concealed by his crimson-red tunic, are crossed, his gaze absorbed, inspired, his head slightly tilted to show concentration. His tools of the trade, namely lightning bolts, are laid on the ground. Behind him, Mercury, recognizable by the petasus (the helmet), the caduceus he holds in his left hand, and the winged footwear (note Dosso’s oddity, who places real dove wings at the god’s feet), addresses a harpocratic gesture, a gesture of silence, to the young woman behind him, all decked out in garlands of flowers. Even until the late nineteenth century, the literary text from which this singular image was taken was attributed to the Greek Lucian of Samosata, as is also evident from Martinionio’s description. In fact, Dosso Dossi’s source was Leon Battista Alberti’s dialogue Virtus , which was part of the collection Intercenales. The story tells how Virtue, that is, the girl depicted on the right in the painting, asks to be received by Jupiter, as she is forced to suffer the humiliations of Fortune. Forced into a long, nerve-wracking and mortifying antechamber, when she is just on the verge of being received by Jupiter (none of the other gods had in fact received her), she is contemptuously turned away by Mercury, who enjoins her to be silent because Jupiter is not willing to listen to her. “They say that the gods must make gourds bloom in time or take care to make the wings of butterflies more colorful,” says Virtue in the Albertian text. “But how, then, will they always have some more important business to keep me out and not mind me? Yet gourds have blossomed, butterflies fly magnificently, the farmer has taken care that the gourds do not die of thirst, but I care for neither gods nor men.”

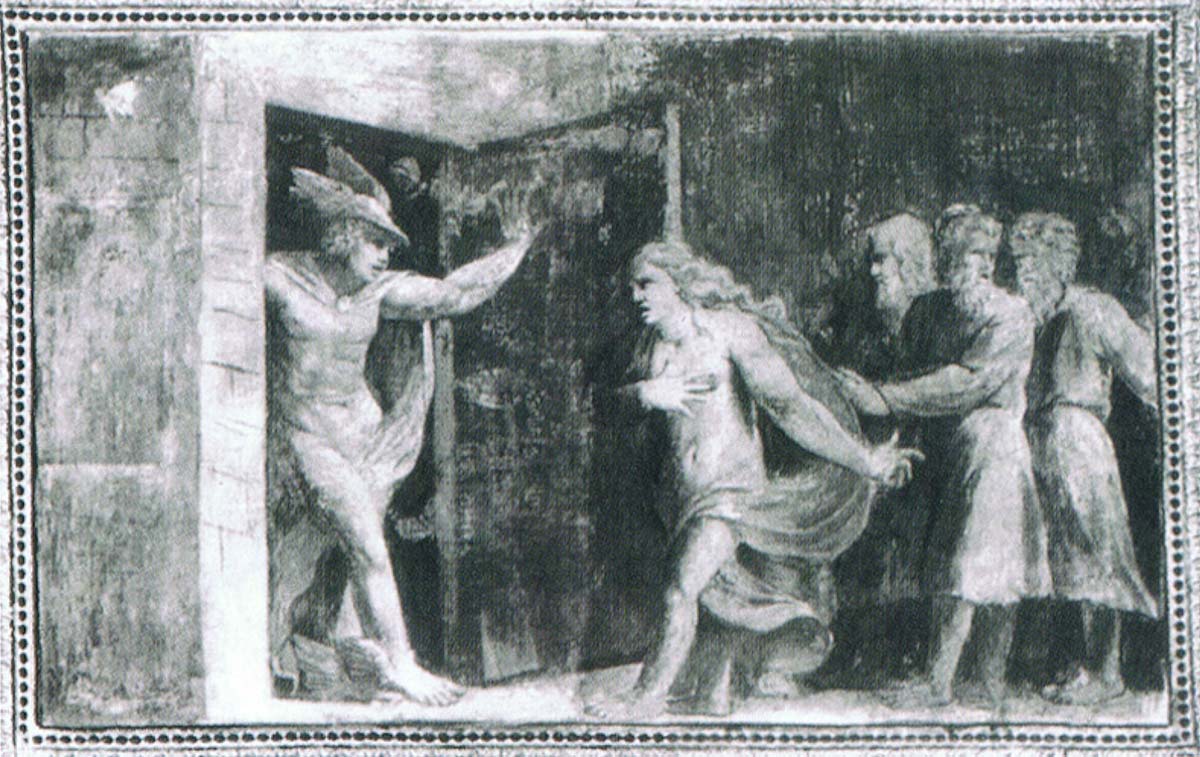

The fable is nothing more than a metaphor to imply that virtue is not cultivated when one engages in frivolous activities, but in fact some elements distance Dosso Dossi’s painting from Leon Battista Alberti’s text. The artist would later make, around 1531, another work on the same theme, for Cardinal Bernardo Clesio in the Castello del Buonconsiglio in Trent: here, however, the scene, more adherent to the text, is different. That is to say, Jupiter is not seen in the painting, and Virtue is depicted in a supplicant position, except to have the door of the Olympian palace closed in her face by Mercury. Dosso Dossi’s free interpretation of the literary source has therefore reasonably led scholars to question the meaning of the allegory, as the element of Jupiter painting butterflies is the result of the artist’s boundless, freakish, visionary imagination. One of the greatest art historians ever, Julius von Schlosser, wrote as early as 1900 that one did not need to go to too much trouble to understand why Dosso had taken all this liberty: just like poets, artists make use of their imaginations, and the reference to butterflies in Alberti’s text would have been enough to inspire the absurd portrayal of Jupiter as a painter. Many years later, in 1978, his idea would be taken up by Paul Barolsky, who argued that it would be risky to try to ascribe an overly intellectual meaning to Jupiter as a butterfly painter, to be read, if anything, as an essay in Dosso Dossi’s playfulness and imagination. Many, however, continue to search for the meaning of the work, dissatisfied with the idea of deeming it merely an imaginative delivery as an end in itself. What, then, is the meaning of the painting?

In 1964, Friderike Klauner considered identifying Jupiter as the allegory of creativity, Mercury as the allegory of patronage , and Virtue as the ability of human beings to resist fortune. In this sense, Mercury would be credited with the central role in the painting: indeed, it is he who protects the artist from the possible reverses to which Virtue can fall. According to Jan Ameling Emmens , on the other hand, it is merely a political satire, relating to events that occurred in 1529 (for which it would therefore be necessary to admit a rather late dating of the painting, lately referred instead to a period around 1524): in this case, it would be an allegory of the behavior, judged to be cowardly, of Francis I of France toward his Ferrara ally. In this case, Francis I would be symbolized by Jupiter, who does not listen to the ally (Virtue, symbol of Ferrara), driven back by a courtier (Mercury). Maurizio Calvesi, in 1969, proposed reading into the painting an analogy between painting and alchemy: it was little followed. In 1982, Gottfried Biedermann suggested reading into the painting an allegory of Spring: the female figure would thus be Flora, goddess of the beautiful season. Again, in 1984 André Chastel proposed identifying the young woman with Rhetoric, because of her garlands of flowers, an element often associated with this art. Eloquence, according to this reading, would try to impose itself on art (Jupiter), but Mercury, who in this case assumes the guise of Harpocrates, god of silence, intimates that she should not meddle with the silent art of painting, which succeeds in achieving extraordinary miracles without the use of words. Dosso Dossi, according to Chastel, would thus have addressed in his own way the theme of the comparison of the arts, the challenge, which engaged many sixteenth-century intellectuals, as to which was the first of the arts. In 1992, Giorgia Biasini resumed Chastel’s reading, adding some elements: the woman, in her view, could be identified as Iris, the goddess of the rainbow (who in fact appears in the landscape). In Jupiter, on the other hand, one could recognize, because of its high characterization, a portrait of Alfonso I, the probable commissioner of the work, who would thus be celebrated here as a patron of the arts.

Later, in 1998, Luisa Ciammitti noted how the Buonconsiglio monochrome has a more distinctly narrative development than the Polish painting, and suggested that the canvas should be related to an influential volume by Andrea Alciati, theEmblematum Liber, published in 1531, but which nonetheless circulated in other forms as early as a decade earlier. According to Ciammitti, Dosso Dossi would have punctually taken up some of the elements found in Alciati’s allegorical descriptions, but without offering new readings of the overall iconography. Among the most recent proposals is that of Giancarlo Fiorenza (2008), who returns to the theme of the young woman as an allegory of Spring (specifically, however, the end of Spring, and for this reason she would be sad). Mercury, with his gesture, is in charge of shushing Spring to allow the transit to Summer: he is the symbol of the month of May. Jupiter, finally, would personify summer, and more specifically the month of June, associated with butterflies. According to Marco Paoli, butterflies would also be to be read in an allegorical sense, as a traditional symbol of the soul, and specifically as the “soul freed from the body by sleep or death”: Jupiter is in fact depicted with his eyes closed. Jupiter, in essence, would be dreaming: according to this reading, therefore, Mercury would protect him from awakening, caused by the presence of the woman, identified in this case as the Aurora. The god, in short, forbids the Aurora from brightening the sky and waking Jupiter. Taking up this reading, in 2015 Polish scholar Marcin Fabianski established a curious 16th-century connection between... Ferrara and Krakow: in 1518, in fact, Sigismund the Elder married the duchess of Bari, Bona Sforza, daughter of the duke of Milan, Gian Galeazzo Sforza, in Krakow. The king of Poland had thus married the niece of Anna Maria Sforza, who had been the wife of Alfonso I until his death that occurred in 1497. On the occasion of this marriage, the humanist Kaspar Ursinus Velius organized a poetic contest between Poland and the “Rest of the World,” we would say today. In this context, Ursinus himself wrote a poem in which he compared Sigismund to Jupiter, recounting how Mercury had roused the king from sleep by flooding the chamber with the light brought by the Aurora. According to Fabianski, this idea was brought to Ferrara by Celio Calcagnini, a humanist and diplomat of the Este court, and would have somehow tickled Dosso’s fancy.

Rather more articulate is another recent reading (2014), that of Vincenzo Farinella, who suggests focusing on therainbow behind Jupiter, “which will have to be understood,” he writes, “not as an attribute of the god, an astrological sign, a symbol of peace or a simple meteorological event, but as the depiction of those celestial ’phenomena’ that, according to Philostratus, ’paint’ the hollow vault of the sky.” So, at a first level of meaning, “we are faced with a true glorification of the pictorial art, through the assimilation of the painter with the supreme pagan deity.” With Farinella also agrees, in the catalog of the exhibition Renaissance in Ferrara, Marialucia Menegatti: “The Jupiter, a cryptor-portrait of Alfonso, should certainly be read as a praise of pictorial art and at the same time as a justification of the interests of the duke, a lover of the fabrial arts and, according to ancient sources, himself a painter.” As, moreover, Farinella had already pointed out, “the sources not only emphasize his very special habits of manual labor in the workshops specially built at the palace, where Alfonso could test his skills of melting metals, working wood at the lathe, and modeling clay pottery, but they also hint at the duke’s desire to paint himself, since in 1493, when he was seventeen years old, he had asked the Este ambassador in Venice to recover colors of great quality.” In short, a great allegory of theotium the duke indulged in so that he could also devote himself to the alchemical activities he was passionate about. The rainbow, in this reading, becomes the bridge between heaven and earth, the butterflies are the substances created by the alchemist, and Mercury the deity who presides over alchemy, keeping the alchemist (the Jupiter-sovereign) away from the torments of virtue, which calls him back to his commitments.

Beyond the various interpretations, none of which has ever clarified the ultimate meaning of the painting anyway, which still remains far from being dissolved (and probably never will be), Dosso Dossi’s Jupiter the Butterfly Painter retains its appeal intact. The work remains, meanwhile, an exemplary essay of Dosso Dossi’s technical virtuosity in shaping his figures with subtle shading, lavishing excellent pieces of backlighting (look at the figure of Jupiter himself), giving the viewer tactile sensations in rendering the robes (observe the creased folds of Virtue’s robe), always in the robes amusing himself with skillful iridescence, and painting the landscape remembering his passion for Giorgione’s painting. One can date the work, according to the most up-to-date critics, to a period around 1524 because the Jupiter Painter of Butterflies is a painting that marks the peak of the first phase of Dosso’s career, but it stands on this side of Giulio Romano’s arrival in Mantua, which will have an impact on the art of his colleague active in Ferrara, not yet found in the Polish painting. And then, the enchantment of this painting lies not only in its singular subject, tackled with singular mastery by Dosso Dossi, but also in the very enigma that the work encloses. And which it is unwilling to reveal. For these reasons we are inclined to consider it a magical painting like few others.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.