"I am sure I will be his continuator": Van Gogh and Adolphe Monticelli, the painter who inspired his sunflowers

If one pays attention, there is a precise moment from which the output of Vincent van Gogh (Zundert, 1853 - Auvers-sur-Oise, 1890) is filled with extraordinary still lifes featuring colorful bouquets of flowers: the summer of 1886. At that time, the Dutch painter was frequenting, in Paris, the gallery of the merchant Joseph Delarebeyrette at 43 rue de Provence, at the suggestion of a friend, the Scotsman Alexander Reid, who was a year younger and whom the artist had known from his time in London where, as is well known, he had moved to work at the local Goupil art house. Vincent had found Reid around that time, since the Scot, the son of a Glasgow merchant, had moved to Paris to study French art, and to purchase works by French artists. Among the works Reid had bought were those of an Italian-born Frenchman, Adolphe-Joseph-Thomas Monticelli (Marseille, 1824 - 1886), who had passed away in the very first days of the summer of 1886, on June 29. Art historian Aaron Sheon has speculated that at that very juncture, and precisely in Delarebeyrette’s gallery, Vincent became acquainted with Monticelli’s art. That there is a connection between Reid and Monticelli is also known from van Gogh’s letters: in a missive sent to his brother Theo on February 24, 1888, Vincent writes that Reid had succeeded in raising the Marseille artist’s prices, and the news was very positive for Vincent and his brother, who at that time were in possession of five works by Monticelli. But however it went, the meeting between van Gogh and Monticelli was one of the most fruitful and useful of his career.

A meeting that, unfortunately for van Gogh, could only come about through the works: the two never knew each other; Vincent probably still had not seen Monticelli’s paintings when the latter disappeared. But through the works he had managed to obtain, he had somehow gained an idea of what the man and the artist must have been like. In a letter sent on August 26, 1888, to his sister Willemien, when the painter had already left Paris to move to Arles, he makes mention of a painting by Monticelli, a Vase of Flowers that was at Theo’s house (and is now instead kept at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam), addressing a rhetorical question to Willemien: what could be said about the painting? “He was a strong man,” Vincent wrote, “a little unbalanced, sometimes even a little much, and who dreamed of sunlight, love and happiness, but who was always frustrated by his condition of poverty, a colorist of extremely refined taste, a man of a rare species, of those who carry on the best ancient traditions. He died in Marseilles, rather sadly, and probably after suffering a real ordeal. Well, I am sure I will be his continuator, as if I were his son or brother.”

And indeed, Monticelli was a rather isolated artist, an artist who is still little known today, despite the great originality of his researches: an originality that, however, was not well interpreted by his contemporaries, who considered his paintings rather bizarre, and for that reason Monticelli’s paintings, which the artist himself sold for little money, never had many buyers, and van Gogh himself testifies that the painter died in poverty (and presumably alone). He had trained with the most “extreme” of the painters of the Barbizon school, the Spanish-born Frenchman Narcisse DÃaz de la Peña (Bordeaux, 1807 - Menton, 1876), who compensated for the theatricality of his views and his still romantic fascination with intricate forests and idyllic landscapes with a technique based on quickness of touch and a more mellow brushstroke than that of his colleagues. Monticelli had met him in 1853, and it was a crucial acquaintance for his career, because it enabled him to abandon the academic tradition in which he had been trained and, instead, embrace a freer painting style, the one for which he later became universally known. Together, DÃaz and Monticelli explored the forest of Fontainebleau in search of vistas to paint in their views. The Franco-Spanish had specialized in small-format paintings that tickled the taste of the collectors of the time: works depicting bathers, nymphs or shepherds immersed in wooded landscapes, reviving a seventeenth-century tradition but also rooted in the eighteenth-century tradition of the fête galante, which involved the depiction of elegant party scenes immersed among verdant forests. Monticelli went further, and in the period of the revival of the Rococo fête galante (several painters, such as Emile Wattier, in those very years devoted themselves to a tired and mannered but capable of satisfying buyers’ expectations revival of the genre in which painters such as Antoine Watteau, Nicolas Lancret and Jean-Honoré Fragonard excelled a century earlier), he hybridized the latter with the spontaneity of barbizonnière painting, resulting in innovative outcomes but which were not fully understood by his contemporaries, who merely dubbed him “the Watteau of Provence,” because “gallant parties” soon became the most important and popular strand of his production.

|

| Narcisse DÃaz de la Peña, Figures with Dog in a Landscape (1852; oil on panel, 43.8 x 29.8 cm; New York, Metropolitan Museum) |

|

| Narcisse DÃaz de la Peña, Pond at Fontainebleau (1875; oil on panel, 45.4 x 55.7 cm; New York, Brooklyn Museum) |

|

| Adolphe Monticelli, Ladies in the Garden (1870; oil on panel, 38.7 x 61.7 cm; Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery) |

|

| Adolphe Monticelli, Scene in a Garden (ca. 1875-1878; oil on panel, 39.4 x 61.9 cm; New Haven, Yale Art Gallery) |

In reality, Monticelli was more than just an epigone of Watteau and colleagues. Having approached, as we have seen, the painting of the Barbizon school as early as the 1950s, by the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the following decade he had already matured a full understanding of the innovations of the Impressionists (the Marseillais was in fact present in Paris around 1870), although many divergences divided him from them, beginning with the use of light, which in Monticelli is much heavier and oppressive (the exact opposite of what occurs in Impressionist paintings), and the very tone of the composition: when Monticelli imagined his works, rather than the snapshot of an impression, he thought of a musical symphony (the famous critic Camille Mauclair, in 1902, reported a reflection by Monticelli, which he said had been reported to him by others, that the painter from Marseilles would one day say that “what my paintings depict, women, parks, peacocks or flowers, are nothing but decoration, while the colors are the orchestra, and the light is the tenor”). Experimentation after experimentation, trying out a wide variety of subjects, in a progressive manner, Monticelli arrived, in the 1970s, at the elaboration of a style that had never been seen before, completely personal, made up of rich and mellow brushstrokes, with details often in relief, warm and intense colors, reminiscent of the painting of Delacroix, all governed by a strong sense of harmony. A painting that, judging by those who appreciated it (van Gogh above all), was able to give substance to the sensations the artist felt (even if it was probably born with the intention of making the gallant scenes resemble precious tapestries: the technique had then undergone further evolutions until it arrived at that full-bodied material that van Gogh loved). “I think back to what I was looking for before I arrived in Paris,” Vincent wrote in a letter to Theo from Arles, September 18, 1888, “and I don’t know if anyone before me has ever spoken of ’suggestive color.’ But Delacroix and Monticelli, even without having spoken of it, did.” And the van Gogh brothers, indeed, have always shown a certain enthusiasm for the art of the Marseillais.

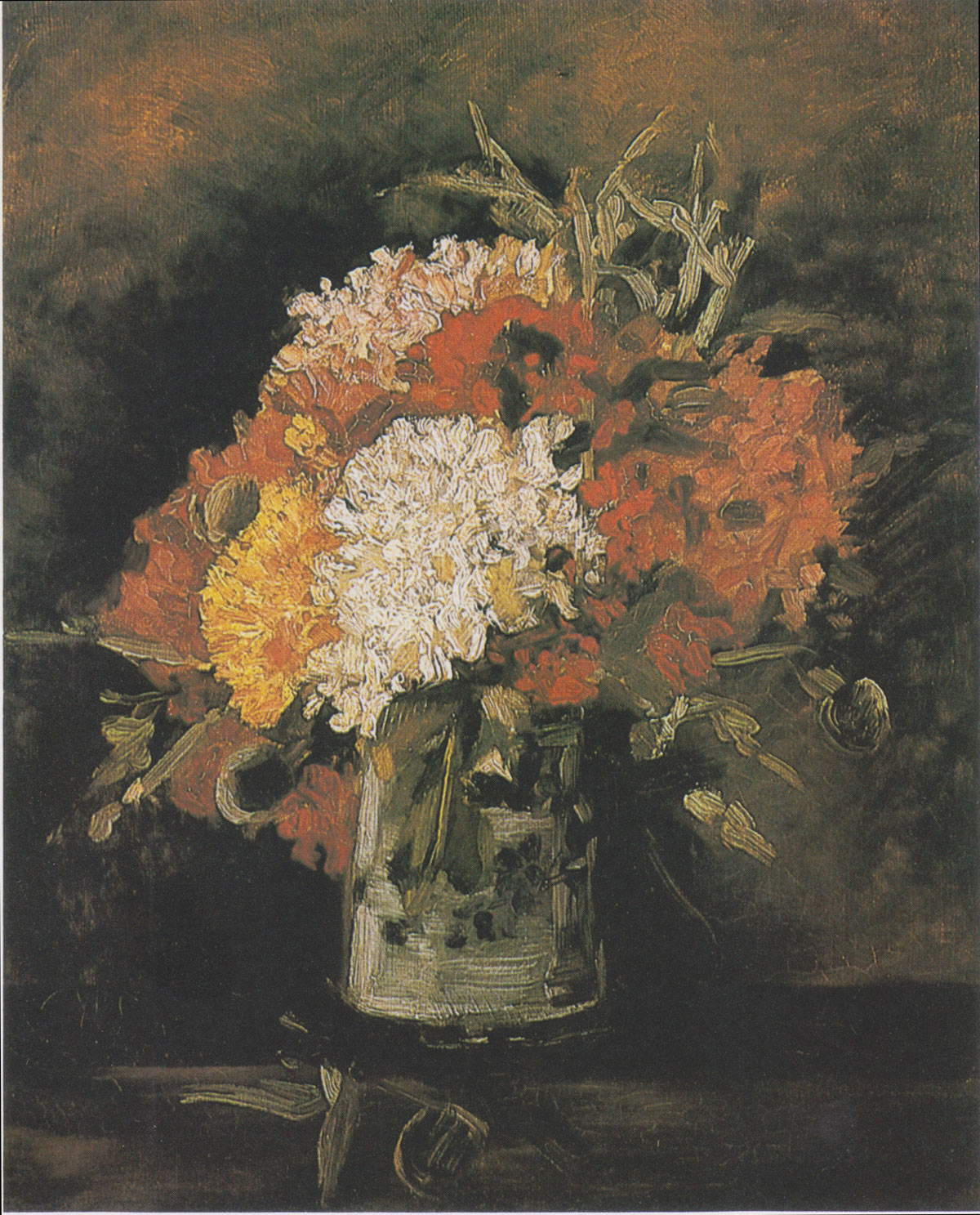

The Vase of Flowers now in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam was probably a gift Reid had given van Gogh: the Scotsman’s purpose was in fact to spread awareness of Monticelli’s art, though not for cultural purposes: Reid had staked a great deal on Monticelli and wished to raise its prices... and would end up succeeding, as van Gogh himself states in the letter above. Moreover, the Flower Vase is often mentioned in his correspondence, and it is a work that Vincent and Theo admired greatly. The light coming in from the left brings out the colors by defining, almost in relief, a vase with a body that almost resembles a mosaic, placed slightly off-center to break the symmetry of the composition. Depth is simply suggested by the long shadow cast on the table. The flowers are built up through short, dense brushstrokes, spread quickly and irregularly, without finishing. The Vase of Flowers is a painting that succeeds in renewing a genre that was particularly in vogue in France at the time, and the author was able to give his flowers a new brilliance and freshness, which elicited great appreciation from Vincent. These are flowers that vibrate: of this, van Gogh was fully aware. When he thought about the Vase of Flowers, he felt that Monticelli was, in his opinion, the only artist capable of perceiving color with such intensity: the flowers resemble precious gems, they manifest an unprecedented chromatic richness, they emerge from the painting thanks to Monticelli’s very special technique, to which van Gogh tried to refer. It is in a missive sent again to Theo, from Arles, on March 25, 1888, that Vincent describes what he feels when looking at Monticelli’s Flower Vase. The painter writes to his brother about the fact that an acquaintance of theirs, the Dutch dealer Hermanus Gijsbertus Tersteeg, who worked at Goupil’s, had expressed an intention to buy a painting by the Frenchman. “You should tell him,” Vincent wrote to his brother, "that in our collection we have a bouquet of flowers that is more artistic and more beautiful than a bouquet by DÃaz. That Monticelli sometimes took a bouquet of flowers to bring together, on one painting, the whole range of his richest and most colorful hues. That we have to go straight back to Delacroix to find a similar level of color orchestration. And that we know of another bouquet of very good quality and at a reasonable price (I speak of the painting that is at Delarebeyrette’s), and that we consider it far superior to Monticelli’s figure paintings."

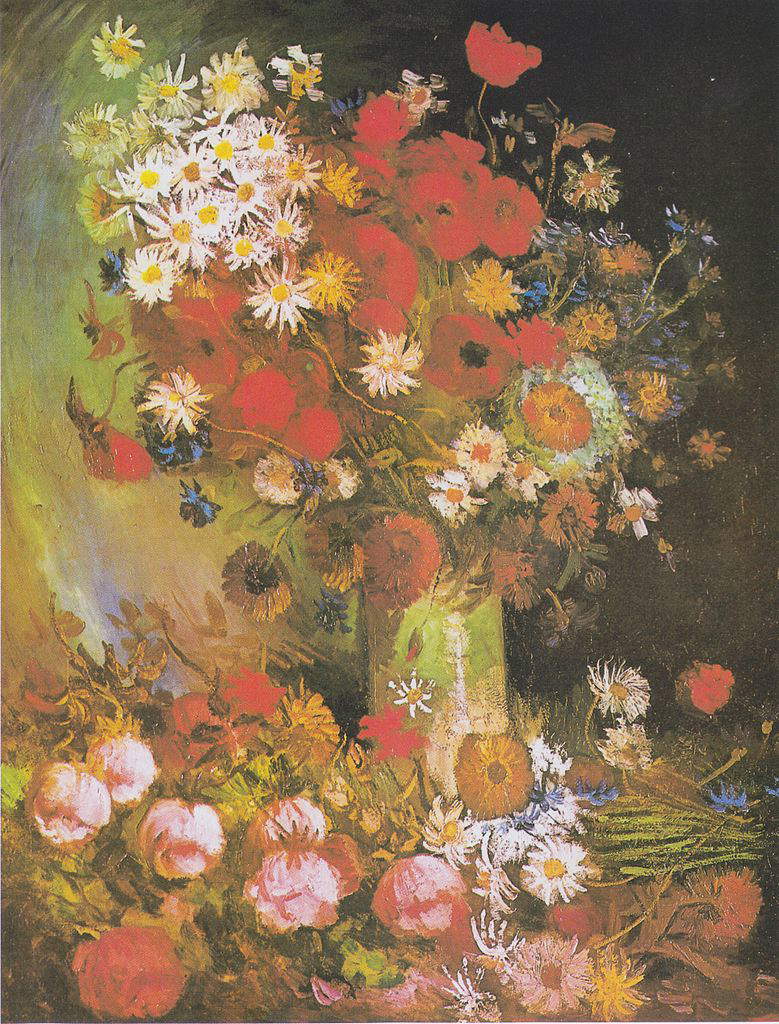

Monticelli can be considered among the artists who were able to suggest van Gogh to the point that he completely changed the way he painted. Vincent, after a long stay in Nuenen (this is the period of the “peasant” works, such as The Potato Eaters), and after stopping for some time in Antwerp, where he had become acquainted with Japanese prints and became strongly fond of them, had joined Theo in Paris at the beginning of 1886: his brother, who worked in the French capital, had strongly advocated Vincent’s move as in Paris he would be able to attend one of the most fervent artistic centers in the world, with all that would follow. In Paris, Vincent’s palette became lighter and brighter, the atmospheres became lighter, and his brushwork achieved a new immediacy, the premises of which are indeed to be found in Nuenen, but which in Paris he had a chance to mature and express himself to the fullest. One of the earliest paintings in which the turning point in van Gogh’s painting (as well as his dependence on Monticelli) is the Vase with Zinnias and Other Flowers, executed in the summer of 1886 and now in the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, where it has been since 1950 following a purchase. We do not know whether this was really the first flower-themed painting made by van Gogh, who as is known had a great passion for flowers, which became a favorite subject of his art in 1886: friends often bought them for him to paint, and he himself used to buy inexpensive bouquets of flowers for the purposes of his painting. But it is certainly among those closest to Monticelli, as well as among the first in a long series that would go on for a couple of years. Why van Gogh was so interested in flowers was well explained by Theo writing to his mother just in July 1886: the painter was seeking a new vividness for his art, he intended to experiment with brighter colors. Van Gogh’s flowers, after all, can be considered among the most joyful of his works, and this kind of painting was also good for his character, since his brother himself testified that, at that time, Vincent had become more carefree than before, and more appreciated by the people he had to deal with.

|

| Adolphe Monticelli, Vase with Flowers (ca. 1875; oil on panel, 51 x 39 cm) |

|

| Vincent van Gogh, Vase with Zinnias and Other Flowers (1886; oil on canvas, 50.2 x 61 cm; Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada) |

Unable to afford to pay models to pose for him, Vincent fell back on flowers (this is not an assumption: he himself had stated this). And for some time he tried to paint them with the same technique employed by Monticelli and with the same elements: the “Canadian” vase is a clear example. The container is resting on a light table, which nevertheless reflects the light (see the brushstrokes on its surface, which are more spread out and compact than those on the bouquet), some glow lingers on the ceramic exactly as it did in Monticelli’s vases, and the flowers stand out against a somber background that brings out the splendor of their colors. There is no parsimony in the use of color, which is spread in large quantities to outline the flowers with stubby but luminous brushstrokes (and with the same color declined in slightly different ranges to give a greater sense of movement) that can almost bring the flowers to life. Note how van Gogh’s Zinnias is close to another Monticelli painting, the Bouquet held at the Phillips Collection: Duncan Phillips, the collector who assembled the important collection, believed that Monticelli was the link between Delacroix and van Gogh. And it was the Dutch painter himself who, for that matter, considered Monticelli close to the great French Romantic painter. Monticelli was probably familiar with the color theory of Delacroix, who used contrasts between different hues to accentuate the dramatic effects of his paintings and to communicate an atmosphere or feeling, and juxtaposed complementary colors to achieve greater luminosity (not coincidentally, Delacroix had long studied the paintings of Paolo Veronese, the greatest ever in the use of complementary colors). “Monticelli, a logical colorist,” Vincet wrote to Theo from Arles on July 1, 1888, “capable of following the most ramified and subdivided calculations on the range of hues of which he sought balance, certainly worked by lapping his brain, as both Delacroix and Richard Wagner had done.” And again, “I think very often of that excellent painter Monticelli, who according to people was a drunk, a madman, when I see myself coming back from that great mental effort in balancing the six essential colors, red, blue, yellow, orange, violet, and green.” The results of this effort were, at first, works such as the Vase with Zinnias and Other Flowers in Ottawa, or even such as the Vase with Carnations in the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam, or the Vase with Cornflowers, Poppies, Peonies and Chrysanthemums now in the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, and again the Basil with Sunflowers, Roses and Other Flowers in the Kunsthalle in Mannheim (the latter two characterized by intense experimentation with complementary colors).

For van Gogh, flowers were, in essence, a subject on which he continued to practice, so much so that, in the summer of 1886 alone, there were about thirty-five still lifes with flowers painted by the Dutch painter. As the years went by, van Gogh’s painting would later break away from that so faithful to Monticelli and become more stylized, more tormented, more expressionistic: an example of this is the Bouquet of Flowers in a Vase now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, a painting that is, moreover, quite difficult in that it is not mentioned in van Gogh’s correspondence, and is variously dated: there are those who consider it a work made between 1886 and 1887, and those who consider it a painting made in the last months of his life, in 1890 since it shares many elements with the landscapes Vincent painted in Auvers-sur-Oise: the color palette, the thicker and “geometric” drafting, the sinuous and swirling brushstrokes, and the modeling with a more graphic than pictorial flavor. Art historian Joseph J. Rishel, former curator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in a publication on the Annenberg Collection at the Metropolitan New York (the core holding the work mentioned above), draws a comparison between Bouquet of Flowers in a V ase and Monticelli’s Vase of Flowers, which the van Gogh brothers had in their collection. “Monticelli,” Rishel writes, “has the same density as van Gogh’s, the contrasts of colors spread with rapidity, from dark to light (without calculations on complementary colors), and all on a surface that is covered with with brush strokes that have the same degree of impasto. But Monticelli’s image, which casts a shadow, is made with less intensity than van Gogh’s, which spatially is more drawn on the surface. In van Gogh, the table, and the image itself, dissolve in dashed brush strokes, which gives the painting a more visionary and less studied quality by comparison with Monticelli’s, even though in the older artist’s paintings van Gogh found (as he would find in Delacroix’s paintings) the way to leave behind both his earlier, darker manner and the coloristically more analytical paintings of his contemporaries.”

|

| Adolphe Monticelli, Bouquet (c. 1875; oil on panel, 69.2 x 49.2 cm; Washington, Phillips Collection) |

|

| Vincent van Gogh, Vase with Carnations (1886; oil on canvas, 40 x 32.5 cm; Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen) |

|

| Vincent van Gogh, Vase with Cornflowers, Poppies, Peonies and Chrysanthemums (1886; oil on canvas, 99 x 79 cm; Otterlo, Kröller-Müller Museum) |

|

| Vincent van Gogh, Basin with Sunflowers, Roses and Other Flowers (1886; oil on canvas, 50 x 61 cm; Mannheim, Kunsthalle) |

|

| Vincent van Gogh, Bouquet of Flowers in a Vase (1887?; oil on canvas, 65.1 x 54 cm; New York, Metropolitan Museum) |

|

| Vincent van Gogh, Sunflowers (1888; oil on canvas, 92.1 x 73 cm; London, National Gallery) |

Van Gogh’s research would later lead to his most famous series, the Sunflowers, capable of combining the warm sun of the Midi, the south of France where the artist had moved in 1888, and the experiments in color that the artist had been conducting in Paris for a couple of years. There are connections between Monticelli and the Sunflowers, and we find evidence of them in the letter van Gogh wrote to Willemien, discussed above. In this missive, the painter told his sister about his latest project: he was making a painting depicting a vase of sunflowers. The one that is now in the National Gallery in London and has become one of his most famous paintings. It is one of five known versions of the painting (in addition to the destroyed Japanese one and one kept in an American private collection) that are housed in museums around the world. By choosing these flowers as his subject, Vincent van Gogh wanted to express the beauty of nature, the warmth of the south, and probably also different feelings: gratitude, happiness, and a sense of friendship. We can only say here that, with his Sunflowers, van Gogh also intended to establish, expressly, an ideal connection with Monticelli, with the artist, with the man.

The letter to Willemien is still the key to understanding this sense of his deference to the unfortunate French painter. As it turned out, Vincent had declared that he felt he was his continuator. And later, he would not only explain why, but also why he intended to do just that with the Sunflowers. Indeed, Vincent wrote to his sister on that August 26, 1888, at the height of the Provençal summer, that “Monticelli is a painter who has rendered the Midi with his full yellows, with his full oranges, with his full sulfur. Most painters, not being colorists proper, do not see these colors, and consider the painter who sees with other eyes than theirs to be insane. This is to be expected. So I have already prepared an all-yellow painting, of sunflowers (fourteen flowers), in a yellow vase, against a yellow background. And I expect to exhibit it some day in Marseilles. And you will see that there will be some Marseillais, or someone else, who will remember what Monticelli once did and said.”

Reference bibliography

- Sjraar van Heugten, Van Gogh and the seasons, Princeton University Press, 2018

- Colin B. Bailey (ed.), The Annenberg Collection: Masterpieces of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, The Metropolitan Museum, 2009

- Ronald de Leeuw (ed.), The Rijksmuseum Vincent van Gogh, W Books, 2005

- Stephen D. Borys (ed.), Post-impressionist masterworks from the National Gallery of Canada, National Gallery of Canada, 2000

- Judith Bumpus, Van Gogh’s flowers, Phaidon, 1998

- Aaron Sheon (ed.), Monticelli, his contemporaries, his influence, exhibition catalog (Pittsburgh, Museum of Art, Carnegie Institute, October 27, 1978 to January 7, 1979), Carnegie Institute, 1978

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.