I am an Etruscan: Marino Marini and the relevance of Etruscan art

“I look to the Etruscans for the same reason that all modern art has turned back skipping the immediate past and has gone on to invigorate itself in the most genuine expression of a virgin and remote humanity. The coincidence is not only cultural; but we aspire to an elementarity of art.” It was in these terms that the great Marino Marini (Pistoia, 1901 - Viareggio, 1980) spoke, for the first time, of Etruscan references in his art. The statement was reported by Antonio Corpora in his survey of the 1948 Venice Biennale, in the columns of a newspaper of the time, Il Sud Attualità . It is interesting to note that the artist had begun to speak relatively late about Etruscan influences on his art, especially when one considers that these suggestions characterized Marino Marini’s work from the very beginning and were so strong that they also conditioned his image among the public. Obviously, the figure of Marino Marini is decidedly more complex: a multifaceted artist, firmly anchored to the roots of his land but up-to-date, modern and capable of absorbing cues from every experience, giving an international breath to his art.

Between 2017 and 2018, the exhibition Marino Marini. Visual Passions, set up first in the artist’s hometown, Pistoia, at Palazzo Fabroni (from September 16, 2017 to January 7, 2018), and then in Venice at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection (from January 27 to May 1, 2018), as the first major retrospective on the artist, intended to retrace Marino Marini’s experience in order to reread it from every point of view. And in this journey, Etruscan art represented a starting point. Barbara Cinelli, curator of the exhibition, explains to us that characteristic of the culture of the time was “the search for a national alternative to the African and Oceanic primitivisms, typical of the European avant-garde, which found in the Etruscan archaeological discoveries the confirmation of an Italic primacy, a primacy that was very dear to the official culture of the 1920s. Etruscan sculpture appeared the genetic element of that straightforward realism that Italian art wanted to recover, and offered at the same time the nobility that came from history.” The element that, in the eyes of the artists of the 1910s and 1920s, distinguished Etruscan art from Greek art or the exotic idols of Africa and Oceania that French artists looked to above all, was thehumanity that emerged from the works made on Etruscan soil. In Daedalus, the magazine founded by Emilio Bestetti in 1920 and directed by Ugo Ojetti until the end of its publications in 1933, Alessandro Della Seta wrote an article in 1921 in which he argued that “figures were not for the Etruscans gods and heroes made sublime by myth; the subject did not present itself grave of deep inner meaning; Etruscan art ended up discerning in them only human men and actions. So instead of ascending to the spheres of the ideal, he stopped on the ground to grasp this side of humanity. He made them really working figures, he wanted to see them move in space, he enhanced their character of action with modifications of form.”

Marino Marini was not immune to the fascination of Etruscan art, especially since that art was a specific feature of his cultural substratum. The Etruscan component was dominant in the early part of his career, during his younger years, but as his career continued his work would open up to other suggestions. “Marino,” Barbara Cinelli continues, “was studying from 1917 at the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence, a short distance from the Archaeological Museum, which holds one of the richest collections of Etruscan antiquities. It is therefore necessary to understand that those testimonies constituted a visual habit for him. But this was precisely in the Florentine period, which closed in 1930 with the move to Milan. There other and different solicitations arrived, and therefore in order to correctly frame Marino’s relationship with Etruscan art it is necessary to take it back to the years 1920 1930, and not turn it into a passe-partout for reading his entire activity.” The years preceding his move to Milan represent a period of fervent activity: in 1927 the artist opened a studio in Via degli Artisti in Florence and exhibited at the III Internazionale d’arti decorative, and then at about the same time he began to collaborate with the magazine Solaria and joined the Gruppo Novecento Toscano with which he exhibited, in 1928, at the Galleria Milano, and in the same year his first participation in the Venice Biennale was recorded. The approach to Etruscan art is substantiated in terms of simplification of forms, to achieve an elementarity capable of capturing reality in its depths. “My love of reality,” Marino Marini would write in his Pensieri sull’arte, “I owe it perhaps to the Etruscans: a reality that appears in forms that have the thickness of the elemental and on whose surfaces light plays. Simplification may, visibly, deviate from nature but it leads back to it because it tends to the essential.”

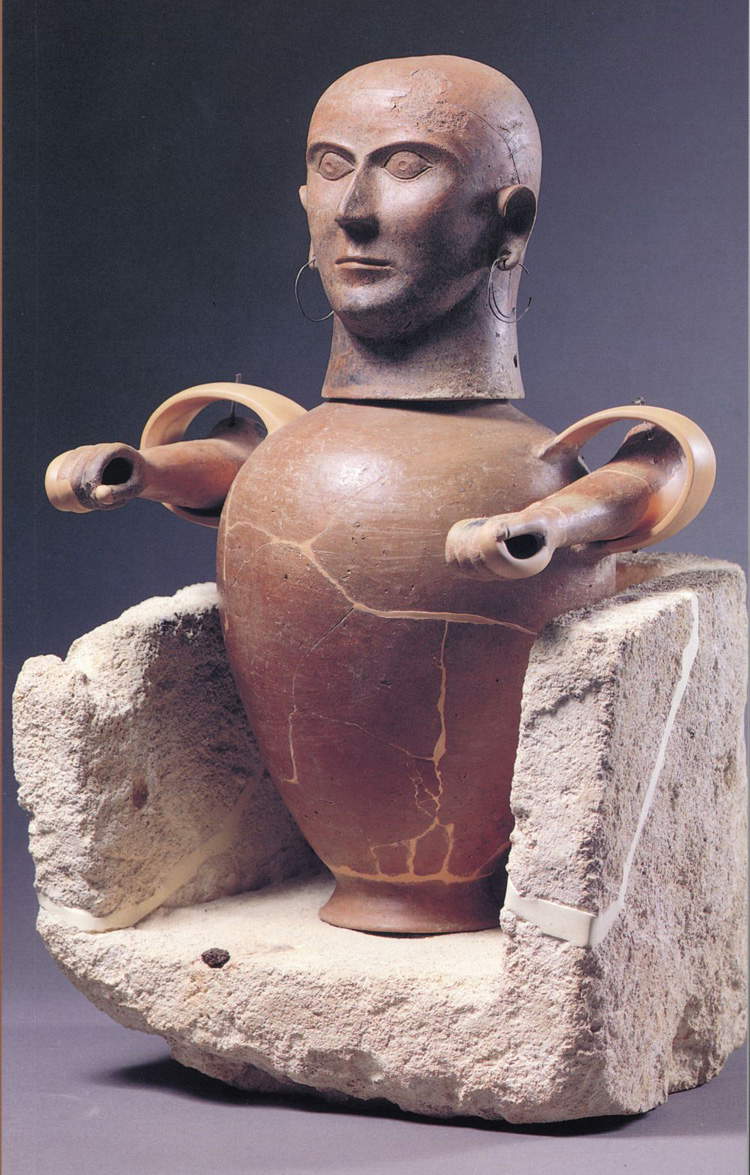

The Visual Passions exhibition aimed to give substance to these proximities by exhibiting, at the opening of the itinerary, a Bust of a prelate by Marino Marini preserved at the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome, dating back to 1927 and therefore placeable among his early works, and an Etruscan bucchero, that is, a refined black and polished ceramic, from Chiusi and currently preserved at the National Archaeological Museum in Florence. It is, in particular, a canopus, or a particular type of cinerary urn equipped with a lid that reproduced the shape of a human head. Interestingly, Marino Marini was a regular visitor to the National Archaeological Museum in Florence: the artist felt the need to establish a deep contact with the art of the ancients. A contact that, in the Bust of the Prelate, is evident in the synthesis of the face and thecassock garment that verges on abstraction, suggested only by a hint of a collar and the row of buttons on the chest. The canopus, in particular, “was useful,” Chiara Fabi has written, “for the reduction of the sculpture to a geometric solid whose synthesis appears diluted through the use of a few expressive emphases (the strong relief of the eyebrow arch, for example).”

However, it is difficult to identify typical characteristics within this path of “love of reality,” partly because, Barbara Cinelli continues, "interpreting an artist’s statements is always complicated, and risky. But wanting to make this attempt, we might recall that Marino always retains an interest in the characteristic, isolated, almost focused detail: from the earliest works, such as Popolo, to the Portraits, such as that of Mrs. Verga, or even to some passages of the Pomone, in which he insists on the notations of the hair styles. Perhaps this is what Marino was thinking of when he alludes to his ’love of reality’; and since these details coexist with an interest in simplification, perhaps they can be explained by those ’forms that have the thickness of the elementary and on whose surfaces light plays’ that Marino attributes to Etruscan sculpture." The Portrait of Mrs. Verga is a work of 1936-1937 and is another sculpture that, although not made in the period in which Marino Marini touched the maximum proximity to Etruscan art, openly refers to the experience of the ancients: the cut of the nose and eyes, the arched eyebrows, the fixed and expressionless gaze, the hair, and the broad face find their most immediate precedents in the heads of the canopic men, with their sober abstraction strongly attached to reality.

|

| Left: Marino Marini, Bust of Pre late or Priest (1927; wax and plaster, 59 x 34 x 27 cm; Rome, National Gallery of Modern Art). Right: Etruscan art, Canopus in buccheroid impasto, from Chiusi (625-580 B.C.; black pottery, 51.5 x 33 x 20 cm; Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale) |

|

| Marino Marini, Portrait of Mrs. Verga (1936-1937; terracotta, 24 x 18 x 23 cm; Florence, Musei Civici Fiorentini) |

|

| Etruscan art, Canopus, from the chamber tomb of Macchiapiana (last decades of 7th century B.C.; pottery; Sarteano, Museo Civico Archeologico) |

It is, however, with Il Popolo, a celebrated terracotta of 1929, that, as Vincenzo Farinella has written, the moment of greatest approximation to that great “mania” for Etruscan art that had pervaded the Italian culture of the time occurs. The work depicts, with intense and archaic realism, a pair of Maremma peasants, caught as they gaze impassively ahead, still embraced, with the woman placing her hand on her man’s shoulders. The physiognomies of the two characters are rough and crude: large, sturdy hands, full, scarred faces, thick hair, no mellowing. Archaic themselves, one might say. The work was born during a stay on the southern coast of Tuscany: “those there,” the sculptor would later say, “were two characters I had sculpted down there by the sea, in Maremma; I went there for the cheese wheels and there were these two characters there. I already felt at that time a rapprochement toward the people; strange, because all the preparation in art was not like that, because when I came to the moment of saying, ’Here in Italy we need to recreate the form,’ it was because unfortunately they were making nothing but ornaments and there was a need to create an absolute form that did not exist.”

The most obvious reference is to Etruscan sarcophagi: think of the Sarcophagus of the Bride and Groom from Cerveteri, now preserved in Rome at the National Museum of Villa Giulia (there is a similar one in the Louvre as well), but also less famous works found in several museums in Tuscany that reproduce married couples on urn lids. With his Popolo, Marino Marini operates a sort of actualization of Etruscan plastic art, reinterpreted in a key of popular archaism apt to highlight the features of the people inhabiting the rural areas of Tuscany. And it is precisely this will to make Etruscan art contemporary that is one of the most interesting features of Marino Marini’s art: a will that, in Popolo, becomes the most relevant element. It is a work that, wrote Alberto Busignani in the catalog of a Marino Marini exhibition held in Venice in 1983, immediately transfers "the cultural reference to the Chiusi sarcophagi into the conception of a universal type in which the popular mood almost seems to allude, in its substance, to the supreme popularity of, say, Zuccone or Donatello’s Geremia : by which we do not mean that the Etruscan sculpture is deciphered in a humanistic key, which would indeed be a distortion, but that it too, myth beyond history, is brought back to that history of the people which from the earliest years seems to be close to MArino’s heart, provided that this people is understood sub specie virtutis, a positive reality in its very being even before its actions." The first version of the work also included arms, but then the sculptor decided to remove them in order to avoid any detail that could provide a narrative foothold to his creation. The very name that Marino Marini chose to give the sculpture, Popolo, moreover clearly reveals the intentions of its creator: to offer the viewer, without any kind of celebratory or, conversely, nostalgic or elegiac intent, a portrait of two commoners capable of highlighting how Etruscan blood still flowed in the veins of the Tuscans, according to the path that, Farinella again suggests, had been traced by Arturo Martini: the work was to be executed “not to see phenomena of creation, of stylistics, but phenomena of human sensibility, of seeing in a head one’s own woman and one’s own friend,” in the name of “that consoling phenomenon which is the reproduction of oneself and of the miseries of human [characters].” Archaism, in essence, became atavism.

|

| Marino Marini, People (1929; terracotta, 66 x 109 x 47 cm; Milan, Museo del Novecento, Marino Marini Collection) |

|

| Etruscan Art, Sarcophagus of the Bride and Groom, from Cerveteri (530-520 BC; painted terracotta, 111 x 191 x 69 cm; Paris, Louvre) |

|

| Etruscan art, Cinerary lid with deceased and lasa (early 4th century BC; fetid stone, 80 x 130 x 39 cm; Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale) |

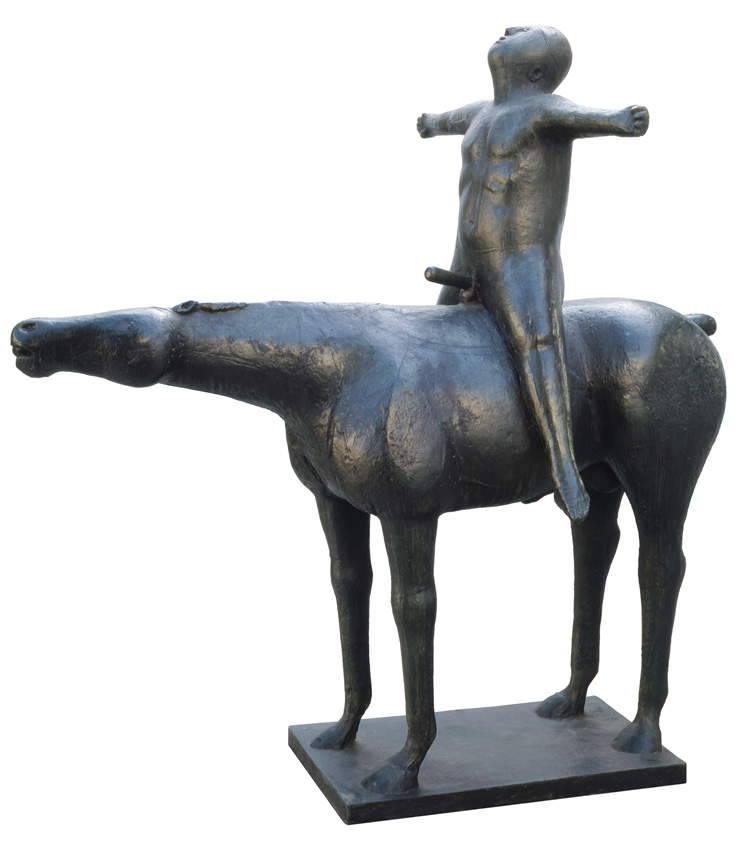

Although open to entirely new stimuli and to the most up-to-date instances of contemporary art, Marino Marini’s art would still not cease to consider its Etruscan base, reinterpreting it, however, through experiences capable of breaking his art out of any cliché. Take the theme of the horse and rider, one of Marino Marini’s most popular strands, especially in the middle of his artistic career. It is true that, for the Pistoiese sculptor, the great equestrian monuments of antiquity, such as that of Marcus Aurelius in Rome, or those that in the Renaissance, from Donatello with his Gattamelata onward, would be inspired by classical statuary, were not decisive, and it is equally true that what fascinated him were, to a greater extent than the examples just mentioned, the horses of Etruscan bronze statuettes or those that Marino Marini saw depicted in Etruscan necropolises. However, in Marino Marini’s horses (the Gentleman on Horseback in the Chamber of Deputies is famous, but the same Angel of the City in the Peggy Guggenheim Collection lends itself well to such consideration) the references are many: they range from the so-called Knight of Bamberg, perhaps the most immediate reference for the Gentleman on Horseback, to the Tang horses of Chinese art, and even to the horses of Picasso’s circuses for the more animated sculptures.

Certainly, some more direct references return (the exhibition at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection made a comparison between a Small Horseman from 1943 and a lid with two horsemen from the National Archaeological Museum in Florence, which Marino Marini probably knew), but reinterpreted in broader contexts and certainly not as determinative as was the case in the 1920s.

|

| Marino Marini, Gentleman on Horseback (1937; bronze, 154.5 x 132 x 84.3 cm; Rome, Chamber of Deputies) |

|

| Marino Marini, Angel of the City (1948, cast 1950?; bronze, 175 x 176 x 106 cm; Venice, Peggy Guggenheim Collection) |

|

| Author unknown, Knight of Bamberg (before 1237; stone, 233 cm; Bamberg, Cathedral) |

|

| Left: Marino Marini, Piccolo Cavaliere (1943; glazed terracotta, 39 x 35 x 14 cm; Florence, Museo Marino Marini). Right: Etruscan Art, Lid with plastic socket in the shape of two horsemen, from Pitigliano (610-590 B.C.; impasto pottery, 20 x 20 cm; Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale) |

It seems undeniable how the desire to refer to Etruscan art conditioned the creation of the myth of Marino Marini as an “Etruscan artist.” A myth to which he himself lent himself: his written output from the 1950s onward, as well as the articles about his production and the interviews he gave, are filled with statements about how Etruscan the artist felt. In 1961, Marino Marini was interviewed by Swedish sculptor Staffan Nilhén, then 32 years old, who asked him for enlightenment about the Etruscan inspiration that animated his works. Lapidary and proud was Marino Marini’s reply, “I am not inspired! I am Etruscan! The same blood fills my veins. As you know, a culture can hibernate, sleep for generations and suddenly awaken to new life. In Martini and me, Etruscan art is reborn; we continue where they left off.” Today, this interest in the Etruscan world appears to be but one of the individual elements that have helped shape Marino Marini’s personality. This image of the Etruscan Marino Marini, concludes Barbara Cinelli, “has its own plausible grounds if reported on a historical plane, which becomes instead hagiography if extended in a timeless plane.” It is therefore necessary “to also bring the contribution of Etruscan art back into a complex horizon of references, without giving it a predominant role.”

Today, therefore, it is interesting to reread these references in order to assess how Marino Marini had managed to make use of the evidence of history, cultural roots, and links with an ancestral past, in order to elaborate a contemporary art fully participating in the revolutions of his time, in dialogue with current events. A complex personality, he returned to Etruscan art “because,” he said, “I wanted to know from the beginning what a form is in sculpture,” but also because “my grandparents were Etruscans, that was my root there,” because the Etruscans “gave me a cue, they gave me a life,” and that at the same time he was able to measure himself with Picasso, with Gothic sculpture, with Henry Moore, with Renaissance portraiture, with Rodin and Maillol, with art forms from the most distant continents. And it is precisely this great eclecticism that continues to make the figure of Marino Marini so interesting.

Reference bibliography

- Barbara Cinelli, Marino Marini, Giunti, 2018

- Barbara Cinelli, Flavio Fergonzi (eds.), Marino Marini. Passioni Visive, exhibition catalog (Pistoia, Palazzo Fabroni, from September 16 to January 7, 2018 and Venice, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, from January 27 to May 1, 2018), Silvana Editoriale, 2017

- Emma Zanella, Giovanna Bonasegale (ed.), Da Balla a Morandi: capolavori dalla Galleria comunale d’arte moderna e contemporanea di Roma, exhibition catalog (Gallarate, Civica Galleria d’Arte Moderna, March 6 to June 5, 2005), Palombi, 2005

- Marino Marini, Thoughts on Art. Writings and interviews, All’insegna del pesce d’oro, 1998

- Maurizio Calvesi, Erich Steingräber, Marino Marini. Anthological exhibition 1919-1978, exhibition catalog (Rome, Accademia di Francia, Villa Medici, March 7 to May 19, 1991), Edizioni carte segrete, 1991

- Mario De Micheli, Marino Marini. Sculptures, paintings, drawings from 1914 to 1977, exhibition catalog (Venice, Palazzo Grassi, May 28 to August 15, 1983), Sansoni, 1983

- Herbert Read, Patrick Waldberg, Gualtieri di San Lazzaro, Marino Marini, lopera completa, Silvana Editoriale, 1970

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.