How to attribute a painting: the Vienna School (Eitelberger, Wickhoff, Riegl, DvoÅ?ák)

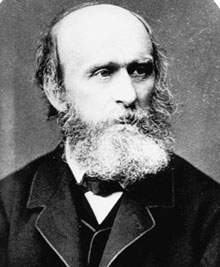

In the last episode of our history of art criticism, we had talked about Julius von Schlosser (1866 - 1938) and introduced the Vienna School, the important group of scholars, of which Schlosser was one of the youngest exponents, who contributed to the radical renewal of the discipline of art history study. And since the contribution of the Vienna School was fundamental, it is only fitting that we devote an appointment in this series of articles of ours precisely to this group of art historians, whose “founder” (we put the word in quotation marks because, as we had said in the article on Schlosser, the group actually had no official character) was recognized by Schlosser in the figure of Rudolf Eitelberger von Edelberg (1817 - 1885).

|

| Rudolf Eitelberger von Edelberg |

In the article on Schlosser, we had talked about how the view of art history as a “whole” of philological relationships between works had been an achievement of the entire Vienna School: the foundations were laid precisely by Eitelberger, who had studied philology at the University of Olomouc (the city where he was originally from) in Bohemia, and in 1839 had been awarded the chair of philology at the University of Vienna. His interests soon shifted to art history, however, and at the same Viennese university he was the first lecturer to hold the newly established chair in art history. A cultured, refined and modern personality with liberal tendencies, Eitelberger achieved the result of considering the work of art as an object in philological relation to other objects. Eitelberger was also the first scholar to emphasize those Quellenschriften (“Written Sources,” a name the scholar also gave to a series of source publications for art history) that would later become the intense object of systematic study by Schlosser. Another pioneering merit to be attributed to Eitelberger was the insight to put university and museum in a position to collaborate: the scholar himself founded the Österreichischen Museum für Kunst und Industrie (Austrian Museum for Art and Industry). Eitelberger believed that research could not do without the two institutions, which were seen as complementary to the work of the art historian, so much so that the scholar often held his lectures in museums, in front of the works of art under study. A tradition, this one that was inaugurated by Eitelberger, that was also destined to take root in Italy, where for decades superintendencies and universities have closely collaborated (and hopefully will continue to do so for a long time to come).

|

| Franz Wickhoff |

Prominent among Eitelberger’s successors was Franz Wickhoff (1853 - 1909), who was a student of Theodor von Sickel and Moritz Thausing, and it was the latter who succeeded him to the chair of art history at theVienna State University. One of Wickhoff’s starting points in the development of his conception of art history were the achievements of Giovanni Morelli, thanks in part to the intermediary of Thausing, to whom we owe the introduction of the Morellian method in Austria: Wickhoff, in particular, was fascinated by the Morellian attempt to devise a scientific method for art history that was as objective as possible. The Austrian scholar applied a logic derived from this method when working on the attribution and dating of Masolino da Panicale ’s frescoes in the basilica of San Clemente in Rome: Wickhoff was convinced that they were the work of Masolino to be dated between 1446 and 1450. A date therefore far removed from that of the frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel in Florence, in which, as is known, Masolino had worked together with Masaccio between 1424 and 1425. Wickhoff, who preferred to postpone by several years the creation of the Roman frescoes (now in any case placed by critics around 1428) on the basis of an alleged influence the Tuscan artist would have received from Pisanello, who was present in Rome between 1431 and 1432, believed that the archaizing elements typical of Masolino’s art were a characteristic feature of his art, which the artist would continue to use throughout his life, despite the fact that the younger Masaccio had introduced, as we know, disruptive innovations.

Thus considering art history to be a scientific discipline, Wickhoff began to reject certain patterns that were taken for granted, causing certain moments in art history to be read from a more objective perspective: for example, Wickhoff attributed considerable originality toRoman art and believed that Roman art had been enriched with new elements compared to Greek art. Wickhoff, in essence, went against the assumption of Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717 - 1768), who considered Roman art to be a kind of imitation of Greek art-a prejudice that had conditioned historiography for more than a century. It has even come to be concluded that the history of Roman art began in 1895, the year in which Wickhoff published one of his major works, Die Wiener Genesis (“The Vienna Genesis”), in which the scholar, analyzing the illuminated codex known, precisely, as the “Vienna Genesis” (which Wickhoff considered to be from the fourth century A.D., but which has now been moved two centuries forward), proposed an original vision of Roman art: To the latter, the scholar credited the introduction of original motifs, which he identified as the elaboration of a natural space, the realism that connoted the portraits, and the continuity of the narrative (as was the case, for example, in the reliefs of Trajan’s Column). It is worth pointing out, however, how Wickhoff in no way considered the contribution ofHellenistic art to which, according to more recent views, the innovations that Wickhoff ascribed to Roman art should instead be attributed. Although Wickhoff’s assumptions about Roman art are considered outdated today, it is thanks to him that Roman art became the subject of in-depth study.

|

| Masolino, Scenes from the Life of Catherine of Alexandria: the saint refuses to worship idols, St. Catherine meets in prison with Empress Faustina, Faustina is beheaded (c. 1428; Rome, San Clemente) |

|

| Alois Riegl |

Winckelmann’s positions were to be definitively overcome through the work of another eminent scholar of the Vienna School, Alois Riegl (1858 - 1905): he was trained in the field of jurisprudence, but soon came to art history, and from 1887 he held, for ten years, the post of director of the Department of Textiles at the Österreichischen Museum für Kunst und Industrie founded by Eitelberger. It was through the study of textiles that Riegl began to consider art history as a continuous evolutionary process: indeed, the scholar had noticed that the transformations of the ornamental motifs of textiles throughout history were the result not of random changes but of evolutions in style. This theory, formulated by Riegl in his seminal 1893 work entitled Stilfragen (“Problems of Style”) led him to consider art history as a history made up of ever-evolving changes. It was a conception that derived from the experimental sciences and was well in keeping with the desire on the part of the Vienna School to give scientificity to the study of art history. So, for Riegl (as well as for Wickhoff, for that matter) the study of art history had to be able to identify the transitions and changes that occurred with the passage of time, and not to establish which epoch came closest to a (moreover arbitrary) concept of perfection.

By studying in more detail the reasons why ornamental motifs experience evolutions over time, Riegl came to introduce the fundamental concept of Kunstwollen (literally, “will of art”), first enunciated systematically in the introduction to the 1901 work Die spätrömische Kunstindustrie nach den Funden in Österreich (“The Late Roman Art Industry According to Findings in Austria”). With this term, Riegl intended to explain the evolutions of style on the basis of the creative power that would connote each individual artistic civilization (and not on the basis of a simple development of artistic technique): thanks to Kunstwollen, each civilization produces its own artistic manifestations, discernible in any artistic product. Among other things, through the assumptions of this theory, Riegl came to establish that all art forms should have equal dignity since they were all products of the same Kunstwollen, and this insight led him to attribute to the so-called “minor” arts (such as goldsmithing, miniature and medallistics) the same importance that was accorded to the arts considered “major” (painting, sculpture and architecture): another prejudice was thus overcome. The limitation of Riegl’s thinking consisted in the fact that, for him, Kunstwollen (which we could, moreover, also translate as"taste," although the concept has undergone evolutions throughout the history of art criticism) was the main factor determining the creation of a work of art, and this led the scholar to underestimate the historical and social basis for explaining why a certain artistic expression was made: nonetheless, Riegl was credited with initiating the reappraisal of artistic civilizations (such as Late Antiquity) that had hitherto enjoyed little consideration.

|

| Max Dvořák |

Wickhoff’s successor to the chair of art history at the University of Vienna was a Bohemian scholar, Max Dvořák (1874 - 1921), one of the last important exponents of the Vienna School. In his early works, Dvořák maintained positions close to those of Riegl: thus, for him, too, art history could be represented as a constantly evolving line. However, later on, Dvořák refused to consider the study of art history on the basis of the formal characters of works of art alone: at the basis of every work of art, for Dvořák, there is an idea. This conclusion led him to elaborate the load-bearing concept of his view of art history, which can be expressed as"Kunstgeschichte als Geistesgeschichte,“ ”Art history as the history of the spirit" (although some translate Geistesgeschichte as “history of mentality” or even “history of ideas”: ideas after all, according to such a view, would be the product of the human spirit). For Dvořák therefore, the work of art is not only an expression of a style, or an aesthetic phenomenon, but also a means of knowing the worldview(Weltanschauung) of those who created it. “Art,” wrote the Bohemian art historian, “consists not only in the development of solutions to formal problems, but is also always devoted to expressing the ideas that govern humanity in its history.”

To give an example, Dvořák, in his seminal 1918 work Idealismus und Naturalismus in der gotischen Skulptur und Malerei (“Idealism and Naturalism in Gothic Sculpture and Painting”) believed thatRomanesque art could not be considered as an evolution of the classical tradition, but as an expression of a period in which new ideas and concepts were being developed. Although his method attracted criticism (there were those who said that Dvořák’s theories applied well to the content of works of art, but not to their form), Dvořák is credited with reevaluating entire periods of art history (such as Mannerism) and figures of artists who had hitherto been neglected by historiographies and who are now considered central to art history: the example is that of El Greco, whose rediscovery is due precisely to the work of Max Dvořák. The scholar also went so far as to establish in Tintoretto’s art the beginnings of modern art: in particular, in the last Tintoretto (in that, for example, of theLast Supper for San Giorgio Maggiore), Dvořák identified a visionariness that would have had more to do with the artist’s intuition and sensibility than with the conventional patterns of the style of his era. A visionariness that constituted an irremediable reason for a break with previous art and in fact sanctioned the birth of an artistic experience that was the result of a new idea, one that would therefore not have been possible previously.

|

| Tintoretto, Last Supper (1592-1594; oil on canvas, 365 x 568 cm; Venice, San Giorgio Maggiore) |

Reference bibliography

- Diana Reynolds-Cordileone, Alois Riegl in Vienna 18751905: An Institutional Biography, Ashgate Publishing, 2013

- Matthew Rampley, The Vienna School of Art History: Empire and the Politics of Scholarship, 1847-1918, Pennsylvania State University Press, 2013

- Michael Gubser, Time’s Visible Surface: Alois Riegl and the Discourse on History and Temporality in Fin-de-Siècle Vienna, Wayne State University Press, 2006

- Ricardo de Mambro Santos, Viennese Viaticum: the critical historiography of Julius von Schlosser and the philosophical methodology of Benedetto Croce, Apeiron, 1998

- Eugene Kleinbauer, Modern Perspectives in Western Art History: An Anthology of 20th-century Writings on the Visual Arts , University of Toronto Press, 1989

- Richard Brilliant, Roman art from the Republic to Constantine, Phaidon Press, 1974

- Max Dvořák, Kunstgeschichte als Geistesgeschichte: Studien zur abendländischen Kunstentwicklung, Mäander Kunstverlag, 1973

- Alois Riegl, Die spätrömische Kunstindustrie, Druck und Verlag der Osterreichischen Staatsdruckerei, 1927

- Erwin Panofsky, Über das Verhältnis der Kunstgeschichte zur Kunsttheorie in Zeitschrift für Ästhetik und allgemeine Kunstwissenschaft, 18 (1925)

- Max Dvořák, Idealismus und Naturalismus in der gotischen Skulptur und Malerei, Oldenbourg, 1918

- Alois Riegl, Stilfragen: Grundlegungen zu einer Geschichte der Ornamentik, Verlag von Georg Siemens, 1893

- Franz Wickhoff, Die Wiener Genesis in Jahrbuch der kunsthistorischen Sammlungen des Allerhöchsten Kaiserhauses (15/16), 1895

- Franz Wickhoff, Die Fresken der Katherinenkapelle in S. Clemente zu Rom in Zeitschrift für bildende Künst, 25 (1889)

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.