In the first “installment” of this small series of articles devoted to the history of connoisseurship, we had made a very quick reference (highlighted mainly in the comments to the discussion that arose around the same article) to an important text written in 1968 by Enrico Castelnuovo: the entry Attribution in theEncyclopedia Universalis. We had quoted it because the scholar compared there the method of Giovanni Morelli (1816 - 1891) to that of Sherlock Holmes, and today we call Enrico Castelnuovo into question again because it is in the same pages that the author reconstructed, in broad strokes, the history of attributional methodology by contrasting, to the Morellian method that based on"intuition," the recognition of the importance of which was traced back to the 18th century, when the erudite Giovanni Bottari (1689 - 1775) wrote that “what makes the author of a painting distinguish himself is that whole which presents itself at first to one who has great practice in that manner.” The definition is beyond fitting: according to this way of seeing, the name of the author of a painting would come out of the patterns and general impressions that would make manifest the style of a painter.

|

| Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle |

To be able to best conduct his own work, Cavalcaselle needed a wealth of notes and drawings. The scholar, also a Venetian like Morelli, had studied at theAcademy of Fine Arts in Venice, but had not succeeded in completing his academic course: in fact, he had preferred to abandon his studies in order to devote himself to traveling to discover art, first in his homeland,then throughout Italy, and then in Europe. It was precisely during his travels that Cavalcaselle built and consolidated his reputation as a connoisseur and had the opportunity to come into contact with important personalities of the culture of his time, including the English artist Charles Eastlake, who became director of the National Gallery in London in 1855 and made Cavalcaselle work for some time in the London institute, or the critic Joseph Archer Crowe, with whom he published a celebrated History of painting in Italy(History of painting in Italy.)

|

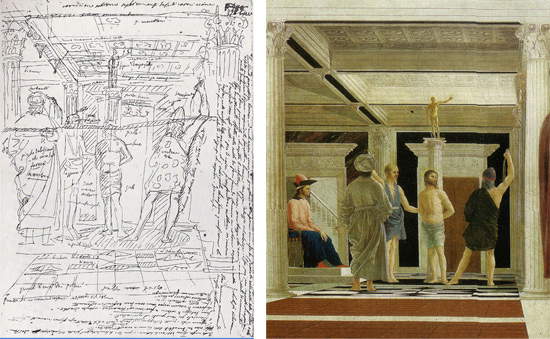

| Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle’s notes on Piero della Francesca’s Flagellation (credit: Fondazione Memofonte). Right, detail of the painting analyzed by the scholar (c. 1460; tempera on panel, 59 x 81.5; Urbino, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche) |

|

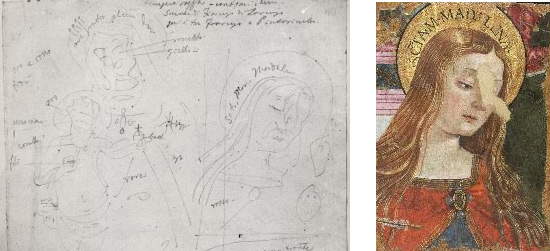

| Notes by Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle on Bartolomeo Caporali’s Altarpiece of the Hunters (credit: Fondazione Zeri). At right, one of the two surviving fragments of the work (1487; tempera on panel, 39.5 x 29.5 cm; Perugia, Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria) |

As anticipated, during his travels, the Venetian scholar often lingered in the activity of drawing: Cavalcaselle lingered in front of works of art, studied them and fixed them on his sheets with short sketches made in pen or pencil, which served him to keep in mind the peculiarities of the styles of the artists he studied. At a time when photography was still very cumbersome and time-consuming, drawing was an indispensable support for the scholar: and for this very reason, Cavalcaselle did not neglect to fix also certain details that came in handy in profiling an artist. In short: if Cavalcaselle’s drawings were texts, we could almost categorize them as summaries of a complete text. Summaries that the scholar, very often, completed with annotations (dates, places, techniques used, state of preservation, comparisons with other works, and so on). A great critic such as Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti (1910 - 1987) was greatly impressed by Cavalcaselle’s abilities, and thus wrote in 1952: “he had an exceptional penetration of the forms, of the characters of originality that distinguished each artist, he noted not only these and every individual technical particularity, but the faults, restorations, additions, and he also had a formidable visual memory, as the numerous references found in his notes attest.”

Cavalcaselle’s method benefited from this continuous activity of study and research supported by graphic and written notes. And it got him great results: famous, for example, is the attribution to Sandro Botticelli of the celebrated Madonna of the Magnificat preserved in the Uffizi. An attribution that Cavalcaselle first formulated in 1864, comparing the painting’s salient features with those of other works by the artist, as well as the masters who influenced him. This is what the scholar wrote in his Storia della pittura in Italia: “One of the first paintings that Botticelli executed should be the tondo on panel that is preserved in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. In it we find the characters succennati.” Such “succennati characters” would be, for example, those reminiscent of Filippo Lippi ’s painting such as, in the figure of the Madonna, “the thick and copious hair falling in curly braids on the sides of the head, on the neck and shoulders, the veil or drape beautifully accommodated on the head, the style of dress with the rich golden bangs, the hair detected with gold in the highlights,” or again, in the angels, the way in which “they are grouped together and around the Virgin of the Child.” But there would also be independent characteristics from those of the master that would denote “a feeling proper” to the pupil, “reunited with a greater study of nature,” and “this is found more particularly in the way the forms, the hangings, the extremities and the fingers are rendered,” but also in the color, which “presents tints that are less vague and luminous than what Fra Filippo used.” Cavalcaselle’s analysis was convincing, and the assignment of the Madonna of the Magnificat to Botticelli was never disputed. Indeed, it was corroborated by the discovery, thanks to the work of scholar Roberta Olson, who unearthed it in 1995, of the allogation document, reported in the late nineteenth century by Gaetano Milanesi (albeit without the exact source).

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Madonna of the Magnificat (c. 1483; tempera on panel, diameter 118 cm; Florence, Uffizi) |

Numerous are the attributions that Cavalcaselle had the merit of formulating first and that still appear valid and indisputable today: among them, we mention the very famous Allegory of the Uffizi, which the scholar attributed to Giovanni Bellini, the Polyptych of Monteoliveto, assigned to Lorenzo Monaco, or even the Crucifixion and the Risen Christ by Pietro Lorenzetti preserved in Siena. The method that Cavalcaselle made his own had a very large number of admirers and continuators (the greatest were probably Max Friedländer and Roberto Longhi) and is still an indispensable starting point for scholars today. Admittedly, it is a method not entirely free of problems (which arise especially for paintings in which the master collaborates with his pupils), but many considered it more reliable than the one devised by Morelli, as well as more valid, since it does not merely take into account a few details repeated almost unconsciously by the artists, but takes into account the entirety of the specifications of a work in its entirety: for these reasons, too, it has been much more successful.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.