How the Etruscans still influence contemporary design, from Giò Ponti to the Italia '90 World Cup

Is it possible to speak of"Etruscan design"? Obviously, it would be a great gamble to find, within the artistic and artisanal production of the Etruscans, characteristics that could be compatible with the modern concept of design understood as “artistic design of a product to be made through the exclusive intervention of the machine and for that very reason reproducible in series” (according to the definition given by the scholar Anna Menichella in a volume by Liana Castelfranchi Vegas dedicated to the minor arts): however, this does not mean that it is not possible to find motifs, lines or aesthetic principles that have guided the action of modern designers. In fact, there are many designers who have been expressly inspired by the objects produced by the Etruscans more than two thousand years ago: the essential lines of Etruscan art and objects, its simple forms, its ability to synthesize, all combined with that sense of elegance that distinguished much of the Etruscans’ artistic and craft production are at the basis of the fascination that this ancient civilization has exerted, at least since the early twentieth century, on contemporary artists and designers. “The straightforward, essential forms of Etruscan plastic,” wrote archaeologist Marcello Barbanera, “suited the demands of rigor and reaction to classical volumes common to the main artistic currents of the early twentieth century such as Cubism, Expressionism, Fauvism, and Futurism.” And from there on, several of those who, in art as in design, went in search of “rigor and reaction to classical volumes,” could not help but look to the objects produced by the Etruscans.

However, it should also be pointed out that the art and craftsmanship of the Etruscans had a seven-century-long history, that styles underwent different evolutions, and that characters (or even certain productions) varied in different cities: for example, canopies were typical of Chiusi and its environs, wall painting in tombs is mainly found in the Tarquinia area, pottery with red figures spread as a result of contacts with Greek civilizations and with the arrival in Etruria of Attic vases (towards the end of the sixth century BC), and so on. It is certainly a complex picture, which, however, does not prevent us from identifying some elements that have made their mark on thecollective imagination: when one thinks of Etruscan art and craftsmanship, it comes almost naturally to think of pottery, bronzes and jewelry.

The evolution of ceramic styles basically follows the evolution of the basic features of Etruscan art, which can be summarized in five main periods: the geometric, so called since, in this phase, the objects present mainly decorations with geometric figures; theorientalizing, characterized by the growth of contacts with the Greeks and the Phoenicians and thus by the acquisition of characters of art coming from these civilizations; thearchaic, so called since it was influenced byarchaic Greek art; and finally the classical and theHellenistic, known in these terms for the usual reasons (i.e., for the resumption of the characters of the various phases of Greek art). However, red and black remain the colors that most characterize Etruscan pottery, but not only that: in the Etruscan frescoes that have come down to us, we notice an abundance of the same colors, which are used mainly for decorative elements (borders, bands, geometric motifs). The same colors were taken up in 2005 by one of Italy’s greatest designers, Ettore Sottsass (Innsbruck, 1917 Milan, 2007), who in the early 1990s made a mirror called Etrusco, reissued in the early 2000s by Glas Italia. Etrusco had a very simple line: a black base on which rest two golden cylinders (gold is another color found in abundance in Etruscan art: it is worth pointing out that the Etruscans loved to show off elaborate jewelry and could boast a goldsmith’s art that probably had no equal in antiquity) supports a platform, also black, on which the mirror is mounted, framed by a red frame. Essentiality and elegance that take us back to the frescoed rooms of the ancient civilization of Etruria, the colors bringing to mind the frescoes themselves, but also the ceramics and jewelry.

|

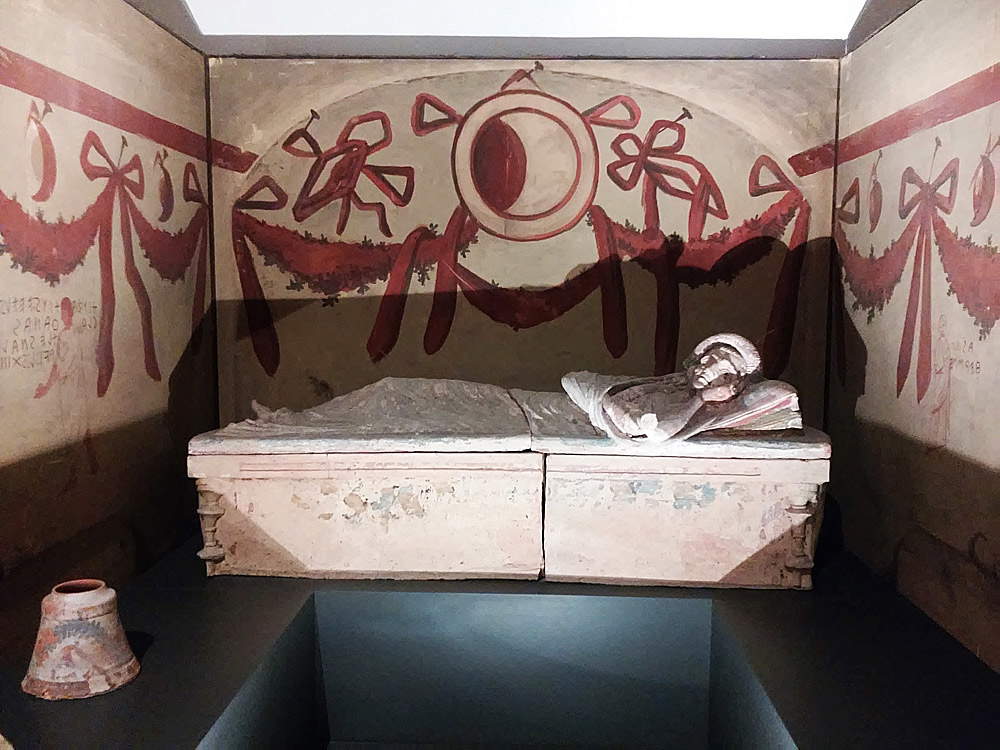

| Reconstruction of an Etruscan tomb at the National Etruscan Museum in Chiusi. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Ettore Sottsass, Etruscan (1990s; wood, crystal and gold leaf, 120 x 45 x 205 cm) |

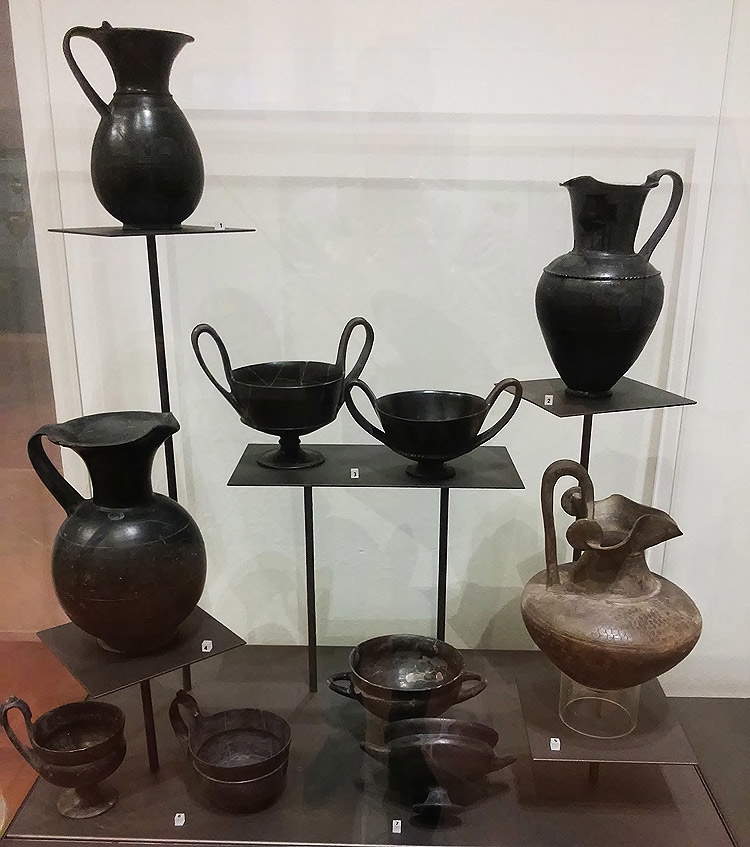

If we talk about Etruscan pottery, it is impossible not to mention bucchero, the most typical form of clay art practiced by these peoples (and it is curious, moreover, to note that the term “bucchero” is an adaptation of the Spanish búcaro, a seventeenth-century term for a clay that was used to make containers in South America). This was a black-bodied pottery, used mainly for the production of everyday objects: to make them, potters used very fine clay mixtures (to which charcoal powder could also be added) that were fired inside kilns suitable for a reducing firing, that is, one that guaranteed the reduction of the oxygen level. The limited presence of oxygen caused chemical reactions that ensured the typical shiny, black coloration that distinguishes Etruscan buccheri and that was much more intense than that which would be obtained by simply coloring the object black after firing. The buccheri had very simple, understated lines and could have incised or relief decorations, although there is no shortage of buccheri without decorations. The bucchero technique was used for the production of pottery: the same use Gio Ponti (Milan, 1891 1979) made of it in 1951 to make some vases that were blatantly based on Etruscan buccheri (and Buccheri was precisely the name he gave to the series). More slender than their ancient counterparts, they were, however, like them equipped with wide, sinuous handles (look, for example, at the Chiusi or Arezzo specimens, produced in southern Etruria and dating from the early 6th century B.C.), had the same geometrizing tendency, and manifested the same finesse.

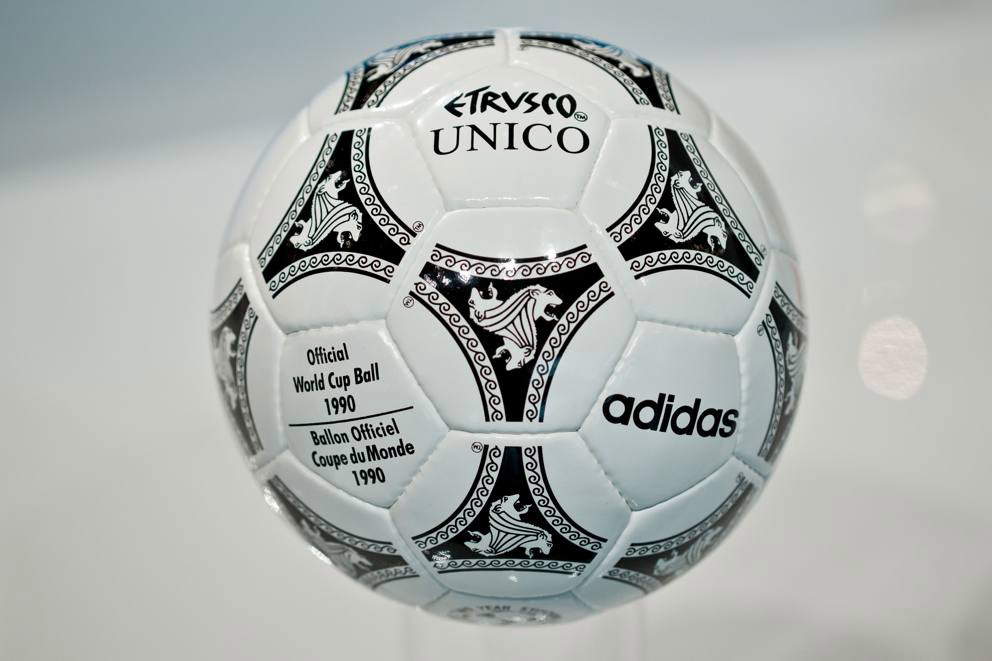

From household goods to sports, the art of the Etruscans even came to exert its influence on soccer balls, particularly on the official ball of the Italia ’90 World Cup (whose name was precisely Etruscan). The base was the same as that of the very famous Tango ball, designed for the World Cup in Argentina ’78 and known because for the first time the classic pattern of black pentagonal panels and white hexagonal panels was abandoned in order to introduce, on the hexagonal panels, triangles that, in the overall design, went to form circles over the entire surface of the object. The Italia ’90 ball, designed by Adidas, in addition to being a highly innovative product since it was the first waterproof ball in history, was also intended to pay homage to the history of Italy by proposing, on the triangles, the wave decorations typical of certain ceramics of the Etruscans (a completely similar motif is found on a vase preserved at the Museo Civico Corboli in Asciano), and the design of three lion heads: these were heads quite similar to those on the chimera of Arezzo, probably the most famous bronze work of Etruscan art.

|

| Collection of 7th-6th century B.C. buccheri at the National Etruscan Museum in Chiusi. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Giò Ponti, Buccheri (1951; ceramic, various sizes). |

|

| Etruscan Art, Chalice (early 6th century B.C.; bucchero worked pottery; Arezzo, Museo Archeologico Nazionale Gaio Cilnio Mecenate). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Etruscan, the official soccer ball of the Italia ’90 World Cup. |

|

| Etruscan painter, Kelebe volterrana from Poggio Pinci (c. 350-300 B.C.; pottery; Asciano, Museo Civico Corboli). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Etruscan art, Chimera of Arezzo (second half or late 5th century B.C.; bronze, height 65 cm; Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

And speaking of bronzes, one of the most extraordinary objects to have come to us from ancient Etruria is the Cortona chandelier, preserved at the Museo dell’Accademia Etrusca in Cortona. It is a complex work from the Hellenistic period (dating from around the fourth century B.C.) and was found in 1840 in the countryside around Cortona: it was immediately acquired by the Etruscan Academy and has not left the museum since. Like many works of the Hellenistic period, the Cortona chandelier is characterized by its exuberant decorativism: in fact, we see that the downward-facing top, the one that was seen by those standing under the chandelier, is decorated with a dense array of figures arranged in a circle, starting from the center and ending at the sixteen outer spouts, where the candlesticks were housed. In the middle we find the face of a gorgon, depicted in oriental manners: with its eyes averted, its nose large and pronounced, its mouth open to show two pairs of fangs, and its tongue stuck out. Around it, on the edge of one circle, we see a swarm of snakes worked in the round. In the next circle, on the other hand, we find depictions of animal tussles, framed by a wave motif found in many other Etruscan works. Finally, the outermost figures, those decorating the spouts, are sirens dressed in a long chiton and with fine clamids on their shoulders, and naked satyrs playing the syrinx, arranged alternately. We have no idea where this chandelier was located, nor what its figures symbolize: given, however, the presence of elements traceable to the religious beliefs of the Etruscans, it is possible to speculate that it was a work from a place of worship, and that it had apotropaic functions. However, it is much more likely that the order of the elements responded more to decorative and aesthetic requirements than to symbolic needs.

The Greek playwright Ferecrates had praised the Etruscan oil lamps in one of his writings, and the appreciation for these works endures even to the present day, so much so that in 2016 a young Florentine designer, Marta Tiezzi, inspired precisely by the Cortona chandelier but also by bucchero ceramics, created Etruscan Light, a chandelier placed in the Public Relations Office of the City of Cortona. A polished iron structure supports the chandelier’s cap, created in bucchero and adorned with fine geometric decorations, inside which burns a lamp fueled by vegetable oil, the same fuel that was used by the Etruscans.

|

| Etruscan art, Chandelier (mid-4th century B.C.; bronze, diameter 60 cm; Cortona, Museum of the Etruscan Academy of Cortona) |

|

| Cast of the Etruscan Chandelier (1932; plaster; Cortona, Museo dell’Accademia Etrusca di Cortona) |

|

| The room of the Etruscan Chandelier at the Museum of the Etruscan Academy of Cortona. |

Finally, one last example of “contemporary Etruscan design” comes fromarchitecture. In Milan, in Palazzo Bocconi-Rizzoli-Carraro, a historic building on Corso Venezia, an Etruscan Museum is scheduled to open for the 2018 holiday season, destined to house a collection of artifacts (which also includes the most complete known collection of vases from the Archaic period) purchased by the Rovati family, a descendant of the Luigi Rovati who founded the pharmaceutical company Rottapharm in Monza in 1961. A 1,500-square-meter museum, developed on the three floors of the building, with spaces also dedicated to a conference room, a library, a workshop for children and young people, a cafeteria and a bookshop. The collection will be set up on the second floor and in the basement. And the most interesting part of the project is precisely the underground section.

The rearrangement of Palazzo Bocconi-Rizzoli-Carraro has been entrusted to architect Mario Cucinella (Palermo, 1960), who, for the basement, planned to create a large pavilion inspired by the tombs of the Etruscans. “A contemporary and highly technological space that will allow the viewer to enter the narrative part of the exhibition,” defined the architect, whose goal is to ideally transport the museum visitor to one of the tombs of Populonia or Cerveteri: the structure features curved lines reminiscent of the circular shape of the tumulus tombs (as well as that of the tumuli that overlooked the hypogean tombs), the pietra serena cladding of the pavilion’s domes is intended to evoke the construction materials used at the time, and the colors of the rooms will suggest all the elegance of Etruscan art. An art that has not yet finished orienting contemporary creativity.

|

| Populonia, Etruscan tumulus tomb |

|

| Mario Cucinella, Project for the Etruscan Museum at Palazzo Bocconi-Rizzoli-Carraro, Milan (2017) |

|

| Mario Cucinella, Project for the Etruscan Museum of Palazzo Bocconi-Rizzoli-Carraro, Milan (2017) |

Reference bibliography.

- Marcello Barbanera, History of Classical Archaeology in Italy: From 1764 to the Present Day, Laterza, 2015

- Ninina Cuomo di Caprio, Ceramics in Archaeology. Vol II 2: ancient working techniques, L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2007

- Mario Torelli, Etruscan art, Giunti, 2001

- Massimo Pallottino, Etruscan-Italic artistic civilization, Sansoni, 1985

- Aldo Neppi Modona, Etruscan and Roman Cortona in history and art, Olschki, 1977

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.