Livid and motionless, the North Sea stretches like an expanse of molten lead, shrouded in a gray haze that fades into infinity. The waves are flat, devoid of vigor, almost suspended in an eternal twilight and reflecting a melancholy-laden sky. This landscape, imbued with a silent desolation, was a laboratory of study and discovery for the artist James Ensor, who often painted brutal storms and dramatic light, so similar to the later works of William Turner and the contrapuntal music of Richard Wagner. In a letter to the poet Pol de Mont he wrote, “You ask me, sir, if I have a particular devotion to such and such a master. I liked Rembrandt very much initially, but my sympathies went, much later, to Goya and Turner. I was fascinated to find two masters who loved light and violence.”

At the age of sixteen, in 1876, he painted a very small oil on cardboard entitled Badkoets op het strand (“Cart on the Beach”). The composition, simple and straightforward, features a small white cabin on four wheels reflecting the melancholy northern European light, while the seascape of Ostend opens up in the background. We are not told whether this particular carriage was inhabited or abandoned, but we can sense faintly how it is not just a cold imitation of reality, but rather an inner landscape capturing an everyday essentiality, in which delicate brushstrokes are entangled with a psychological tension, filtered through the artist’s personality.

A few years later, Ensor had a dream in which he found himself living in that cabin by the sea: his skin slightly abraded by the sun, his body hair covered with saltiness, and his heart light. The small chamber was completely lined with mother-of-pearl and, every night, he dozed off by the side of a beautiful girl. This, however, was only a very sweet fantasy. The Belgian artist never took a wife, while his only child was that Northern light that permeated insistently in every painting. In a 1932 speech he stated, “I have no children, but light is my daughter, light unique and indivisible, light bread for the artist, light crumb for the artist, light queen of the senses, light, light, enlighten us! Give us life, show us new paths that lead to joy and happiness.”

It is the glow that, suddenly and without frills, takes over his works, bounces into them comfortably finding its space and transforms every place by charging it with emotion and nostalgia. Ensor left countless articles, letters and pamphlets on the subject in which he always pursued the same key words that recur obsessively: “light,” “freedom” and “vision.” The latter is not to be read in an esoteric way, but rather with a curious eye, as a lens through which to view and imagine the world and thus, “The first vision, the vulgar one, is the simple, dry line, without a search for color. The second moment is when the more trained eye distinguishes the values of tones and their delicacies,” he says in his Réflexions sur l’art of 1882, published in Le Plume in 1889. “The last is where the artist sees the subtleties and the many plays of light, its planes and gravitation.”

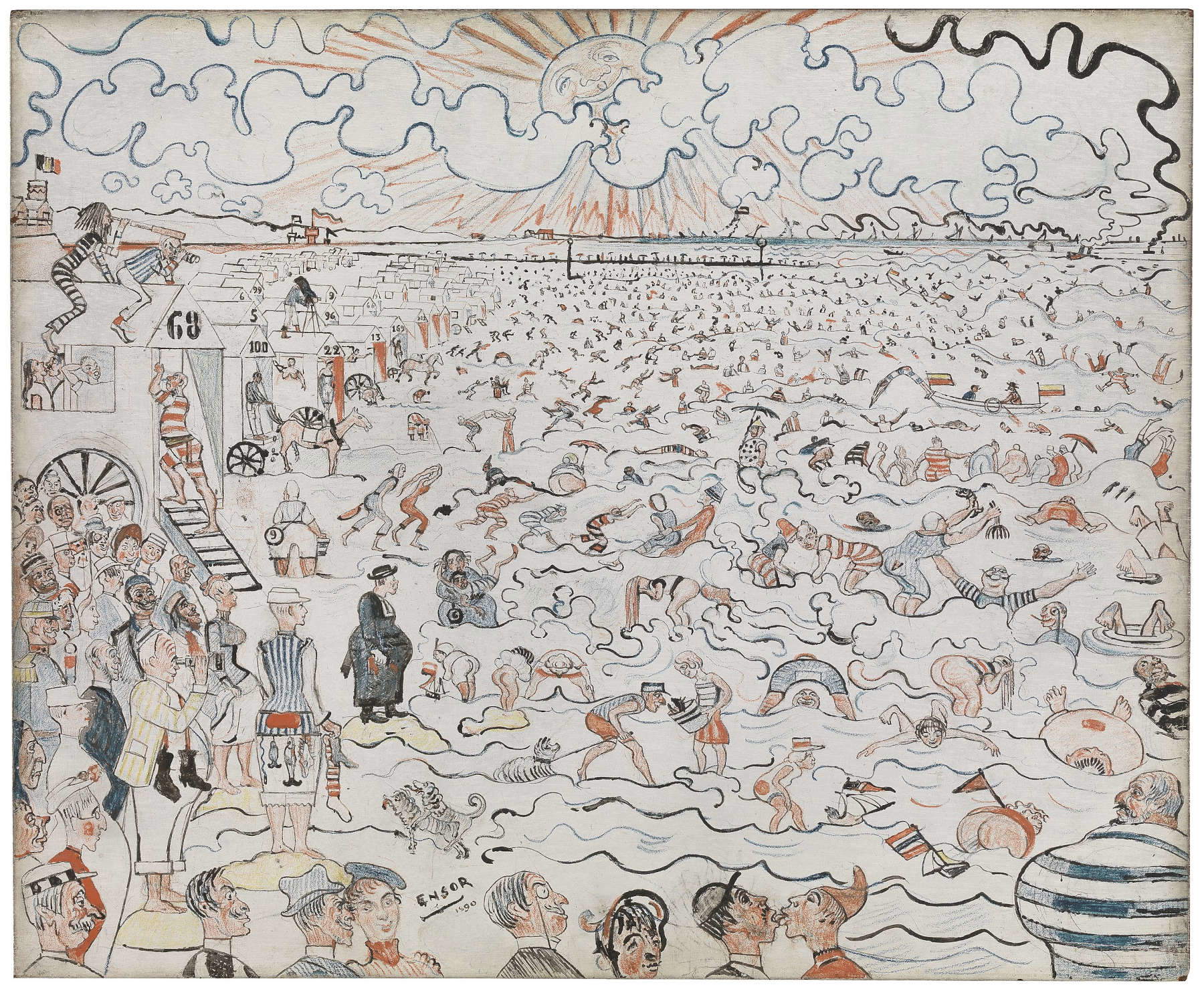

Ensor lived a few hundred meters from the beach and, perhaps because of this or because of his constant walks along the coast, he had a deep and visceral love for his sea. Retracing the steps of the artist’s motionless existence, we should forget everything we are commonly accustomed to in Italy: his is a pelagus of cerulean waves that caresses the very long coastline, a flat and livid place that arouses a sense of monotony and bewilderment, evoking that Kantian concept of the sublime that manifests itself precisely in the boundless extension with respect to the human subject. But the towering dunes, with the rise of beach tourism, were soon removed to make way for flat piers, wooden walkways and endless expanses of cabins. The artist protested fiercely, asking again and again for the courtesy not to deface his beloved sea but, as we can see today as we stroll the 67 kilometers of Belgian coastline, he was never listened to. The much-hated confusion permeated, thus, the 1890 oil and colored pencil work The Baths of Ostend, which depicts an endless number of bathing cabins and even more men, women and children stuck forever in a fleeting moment of idleness and amusement. The literary scholar André De Ridder, wrote how Ensor united “hundreds of these invaders, insulting the sea, with their faults and grotesques, in a mad dance in the water.” He produced a comedy of the absurd in which men, women and children are staged in grotesque and equivocal poses that seem to evoke Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Children’s Games or Proverbs. Climbing to the top of the cabins, three men armed with binoculars peer at the beautiful women on the seashore, while discrete references to the number 69 are made among the white buildings: one of them, in fact, bears the number 68, and two other bathing cabins have a 6 and a 9 as their numbers. The design, predictably, caused quite a stir at the time and was withdrawn during an exhibition of La Libre Esthétique à Bruxelles. During a visit to the exhibition, in the presence of the artists, King Leopold II approached Ensor and, according to his own account, was intrigued and, after carefully observing the work, asked designer Octave Maus to display it in a prominent place within the exhibition. The continuous influx of tourists only emphasized the discontent of the reclusive artist prone to social criticism, who detested the chaos and vulgarity that vacationers brought with them.

Today’s Ostend owes its tourist vocation to the culture of bathing in the sea as a healing process, introduced by the British almost two centuries ago. Initially, the development of tourism was gradual, fostered by the creation of new railway and tram lines, but soon the citizens of Ostend seized the opportunity to profit from this growing flow of visitors. Thus the city was transformed from a modest seaport to an important seaside resort, and even James Ensor’s family, which operated a curious souvenir store, began renting rooms during the summer months to accommodate tourists. The artist’s father, James Frederic, was a distinguished English man, educated, passionate about art and music, but hopelessly alcoholic, while his mother, Marie Catherine Haegheman, was a petty bourgeois Flemish woman hostile to her son’s creative activity. Her family ran, thanks largely to the help of the indefatigable grandmother to whom Ensor was extremely close, a store selling curios, shells, masks, bibelots, and objects imported from the Orient.

Just a few steps from the waterfront, walking for only a hundred meters down the very gray Vlaanderenstraat and turning toward van Iseghemlaan, one comes upon the building, now entirely reconstructed, where the painter set up his first studio. On the ground floor was the gift store run by his mother and grandmother, but death was a dear friend to the artist. In the midst of World War I, he took his mother, only a year later, in 1916, he took possession of his sister’s heart, while in 1917 the curious soul of his uncle, who lived across the street from the artist’s childhood home and studio and who owned, himself, a souvenir store, slipped into her arms.

Ensor was hopelessly alone, but he inherited everything and moved to 27 Vlaanderenstraat, his uncle’s large mansion, abandoning both his maternal home and the place where he created his works. The building is distinguished by large windows that veiled the bizarre gift store where one encounters bulging puffer fish hanging like chandeliers, trinkets and shells of all kinds, plates, photos of the artist, obscure carnival masks and eerie dioramas. As one wanders through the dimness of the store one will come face to face with obscure fish-bodied mermaids and monstrous faces with sharp teeth, created by assembling different animal parts together.

It will certainly not prove an impossible exercise to slip into the artist’s shoes as one climbs inside the building and discovers the reconstructed furnishings after careful restoration, rearrangement and extension of the various spaces. Neurotic, a liar, a slave to his own nightmares and afflicted, it would seem, with pathological misanthropy: this was Ensor, and his home seems to reflect his repulsive harshness and his highly critical outlook on the “bourgeois” art of the time. The spaces he inhabited are thus proposed: crazy, obsessive, rude, eccentric, but at the same time cultured and extremely elegant. Continuing to wander through the rooms of the painter’s mind, one finds oneself before the 1888 reproduction ofChrist’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 (the original resides in the J.Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles). The painting was hung by James Ensor in that blue salon with seemingly narrow walls to house it with dignity. But it was fixed there very late. Before its exhibition at the Palais des Beaux-Arts it first remained locked and rolled up in the artist’s studio with no eyes to defile it except those of a handful of friends, and only when he inherited his uncle’s house in 1917 did he display it in the living room.

James Ensor did not remain cooped up in little Ostend all his life, but traveled without ever straying too far and lived for a time in Brussels to attend the Academy of Fine Arts, which, unfortunately, immediately proved to be a great disappointment. Although he chose as his subject the entry of Christ into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, setting it in the well-known Brussels, his interest lay not so much in religious faith or particular existential issues, but rather in social and human problems. Christ makes his grand entrance to the indifference of the crowd and turns out to be only one of many confused and faceless figures. He ascends on the back of his donkey while around him military, clergy and masked people engage in obscene practices. Christ is Ensor, or rather his self-portrait, who passes through the mode without creating too much noise, too many glances and is incalculable, misunderstood, invisible: a Lilliputian who blends in among an infinity of insulting and banal faces.

Even interiors, in his art, turn out to be reflections of the soul, between light and shadow, perpetually poised between refuge and stage. His home is silent muse, within which the Belgian orchestrated an intense chromatic symphony, shaping his style. The interiors not only reflect, but challenge and aim to surpass Impressionism. They are an arena where the artist explores the human psyche, probing the depths of the soul with brushstrokes of light and color, and the four walls become a cosmos where reality mingles with the imaginary and the everyday with the transcendental. Ensor invites us to cross the threshold, to lose ourselves in the folds of light and shadow and continue the journey through the rooms. The quantities of photographs, letters and reproductions are almost disturbing and the eye, exhausted, is unable to cling to any detail because it is immediately enraptured by another painting, another puppet, another strange chandelier or another eerie doll. One thus finds oneself rudely yanked into what is most priceless in the world: into that mind of an artist who traveled everywhere, between bourgeois interiors and the dense, intimate webs of the mind, never straying too far from his Ostend.

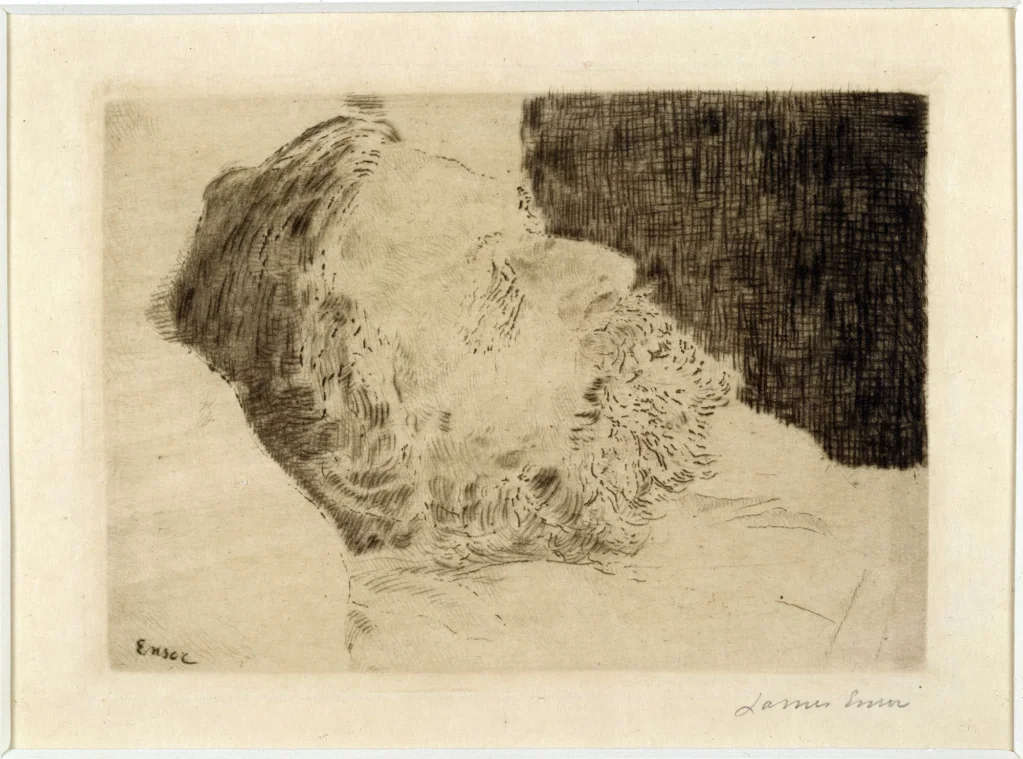

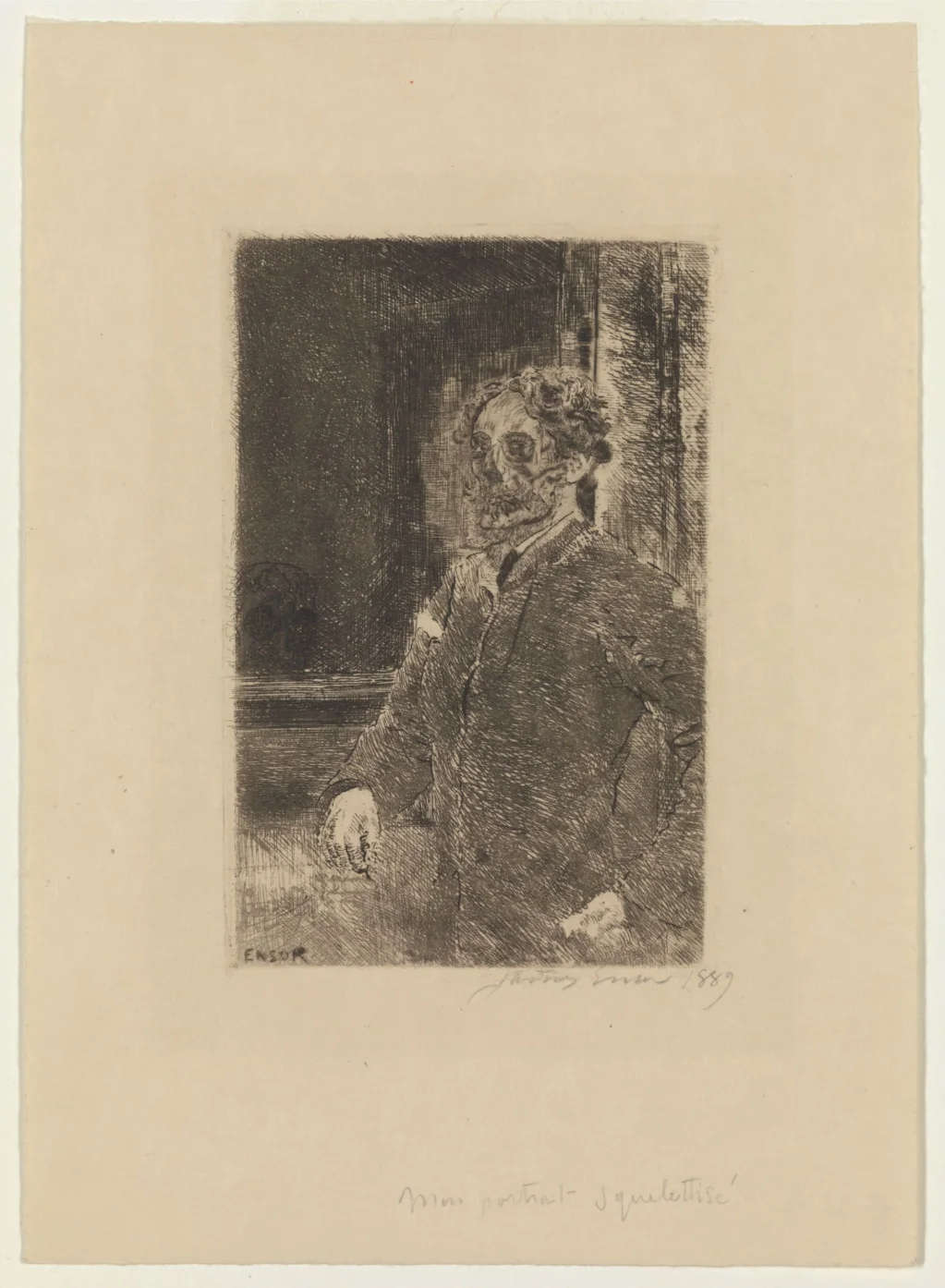

Changing floors, one enters several aseptic rooms that differ sharply from the rest of the structure, in which the artist’s photographs have been preserved, where the eye momentarily finds an artificial order. Unlike his enemy Fernand Khnopff, Ensor never made photographs that could serve, in later years, as documents, but those he used as inspiration were taken by others. One of his earliest works based on a photograph (taken by Ostend photographer Louis Ferdinand Le Bon) was the 1887 drawing My Dead Father, now in the KMSKA in Antwerp, of which he made a drypoint version the following year. The 1889 etching, My Portrait as a Skeleton, was also based on a photograph (this time taken by Ernest Rousseau Jr.) in which the artist stood in the back of the Rousseau house in Brussels during one of his many visits.

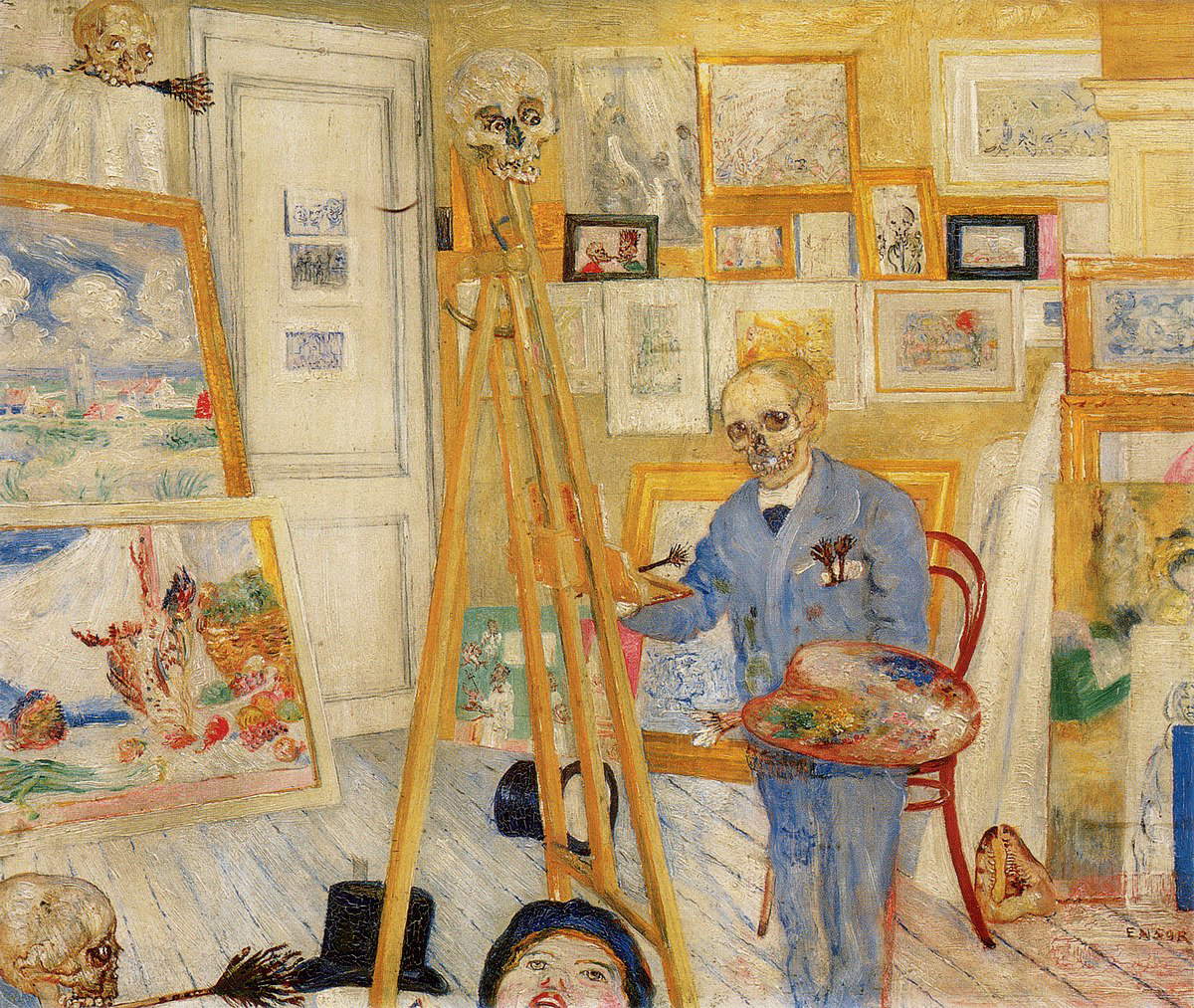

Continuing the exploration, scattered here and there are large dollhouses within which one can timidly peek in and discover, for example, the artist’s studio and childhood home, the walls of which can be glimpsed today by turning one’s gaze toward one of the windows facing north on van Iseghemlaan. In that building, which today has been demolished to make way for a taller, mirrored building, Ensor painted his most famous works, such as Painter of Skeletons in his studio.

In the urban glimpse where he was born, he depicts himself as a pensive skeleton in an attic, in what was once his artist’s nest. This canvas also faithfully copies a snapshot that first appeared on page 38 of La Plume, but it changes the pose: he represents himself erect in front of the easel, with his legs shortened and in a rather classical pattern. Distorting the setting, however, is his becoming bone and dust in a place reminiscent of a souvenir store. The attic is filled with masks, skulls and unusual objects. All the works in the photograph are depicted, meticulously, one by one on the canvas in a kind of self-celebration of his art, where he added a single painting not in the shot, Dangerous Cooks.

He loved his old studio located above the family home, loved its rarefied calm, its composed chaos and oddities, but most of all from there he could serenely paint the rooftops of Ostend and the eye could get lost in that city that was being transformed with unbearable speed by tourism. Ensor, to protect the landscape and monuments published countless writings and called the damage inflicted, first by the bourgeoisie and then by mass tourism, akin to blasphemy and as “crimes against beauty.” Although he was misogynistic, irreverent and neurotic, he manifested a fervent passion and admiration for nature, so much so that in his lifetime he worked for the defense of animals and against vivisection. It was man who was corrupted by vice and deviance, and that was also why the artist masked him.

What was to be recreated were the perceptions, experiences or sensory data existing only in the dark cavity of each person’s skull. As the philosopher Hippolyte Adolphe Taine stated, “external perception is an internal dream that proves to be in harmony with external things: and instead of calling hallucination a false external perception, we must consider them together.” And what strikes me most, perhaps, about Ensor is precisely how quickly he brought this idea to crisis, noting, with surgical precision, that the intimacy of perception implies the narrative intelligibility of painting.

One interesting work of his, Les Masques scandalisés of 1883, turns a familiar anecdote (Ensor’s father’s drinking problem and the effect on his mother) into a masked farce by staging the conflict, focusing on the black spectacles of the female mask and the vacuous surprise of the male mask. The fake faces appropriate the inner drama, are disturbing protagonists of it, coming across as exaggerated but coldly impassive. Similar is Ensor’s use of the skull, which almost always resembles a mask placed over a costumed body, devoid of moralistic references and in stark contrast to colleagues such as Arnold Böcklin or Max Klinger.

In September 1890, the Belgian symbolist playwright and poet Maurice Maeterlinck published in La Jeune Belgique an interesting piece of literary theory entitled Menus propos sur le théâtre, in which he stated how precisely the theater was miserable scenery and how “it is the provisional mask under which the faceless unknown fascinates us.” The actor, according to Maeterlinck communicates the work through his contingent and casual subjectivity, creating a contradiction in the performance and turning the stage into a place of disintegration of the drama. “Poetry wishes to free us from the dominion of our senses and to make the past and the future prevail, while man acts exclusively on our senses and tries to eliminate the invasion.” That is why masks were used since Greek theater: to obviate a problem Ensor demolishes. His masks are intimate, personal, but simultaneously unattainable and a mockery to an audience that mocked him. Their genesis, however, is precise and goes back to theannée terrible of 1887, when his maternal grandmother died and shortly afterward, under mysterious circumstances, his father.

His masks drew heavily from artists he so admired such as Bosch, Brueghel, and Goya. But Bosch put a sinful humanity under the microscope, Brueghel that without filters, and Goya studied the deep darkness of the human soul. Ensor’s were ridiculous, false faces he had known since childhood. Thanks precisely to the family trade, there were countless people who, especially during carnival, would line up in his mother’s souvenir shop to buy disguises and try to win the town’s prize for the most beautiful mask. Although, as stated several times in these pages, Ensor’s was a controversial and introverted personality, he never disdained to participate in that city contest, which he won twice.

We could now imagine the artist strolling through the streets of Ostend and watching the amusing carnival as his heart swung between contempt and admiration. He never had very many friends, and artists who knocked on his door were often received glacially and contemptuously, but some who kept him company during his existence there were, such as the Rousseau family and Emma Lambotte, who wrote to the painter very often. In one letter, in which she seems to share with Ensor the boredom conveyed by uninteresting people, she described the dinner guests at her home as “a group of old gray men and their equally gray wives.” He was similar to the man from Ostend in temperament and ideas, and the two of them could always talk easily, which is why she wished she could have had him beside her during those tedious soirees. But at least, with her in Antwerp, in a prominent place in the dining room, was his self-portrait, which she could look at during dinner, imagining their conversations.

Although the Belgian painter’s friends could be counted on one hand, it would be an utterly wrong exercise to imagine him constantly alone and locked in the half-light of his studio as he engaged in absurd conversations with his dolls and masks. One could not be more distant: Ensor loved to stroll the streets of his city, and, still within walking distance of home, in 1928 he became co-founder of a film club (now dismantled) where avant-garde films were shown and where he could mingle among the people, spying on the younger generation and entering their thoughts. Loved and hated, misanthropic and very sweet, edgy and oyster-hearted, so much is said about Ensor, but never too often is it remembered that he was a man made of flesh, bone, blood, lies, masks and contradictions, like every other person in the world who never fully reveals himself, but always chooses wisely which disguise to wear. He was a man “like a statue,” it was said at the time, as his gait was firm but relaxed and he always wore black, as if he wanted to become a shadow or black hole that captures all luminescence. He sat almost every day, with a few acquaintances, in Café Falstaff on the north side of the Wapenplein (badly damaged during the bombing of World War II and now becoming a pokeria, in continuity with that constant push toward convulsive tourism), sipped scotch or port, depending on the day, and lost himself admiring and scorning passersby, while the sea murmured in the distance.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.