How Lucio Fontana made his cuts. Technical aspects of his "Waiting"

One of the most famous photographs depicting Lucio Fontana (Rosario, 1899 - Comabbio, 1968) is the one taken by the great Ugo Mulas (Pozzolengo, 1928 - Milan, 1973): the image shows the artist, the father of spatialism, as he has apparently just finished making a cut on a canvas with his Stanley cutter. In reality, Mulas would later explain, Fontana had only pretended to cut the canvas: for creative needs, the artist had asked to pose in front of an already finished work, pretending to have just cut it. “If you film me making a painting of holes,” Fontana had confessed to Mulas, “after a while I don’t feel your presence anymore and my work proceeds quietly, but I couldn’t make one of these big cuts while someone is moving around me. I feel that if I make a cut, just like that, just to take the picture, surely it won’t come--maybe, it might even succeed, but I don’t feel like doing this thing in the presence of a photographer, or anyone else. I need a lot of concentration. I mean it’s not like I walk into the studio, take off my jacket, and trac! I make three or four cuts. No, sometimes, the canvas, I leave it hanging there for weeks before I’m sure what I’m going to do with it, and only when I feel sure, I leave, and it’s rare that I waste a canvas; I really have to feel fit to do these things.”

Perhaps, Mulas speculated, it was because of this concentration and meditative dimension that preceded the making of each cut that Fontana had given them the name Waiting. The photographer therefore asked the artist to pose first in front of a still-pristine canvas, and then in front of a finished work.Mulas’ idea, the goal he had set himself with the famous series of photographs taken in 1964 in Fontana’s studio, was to be able to understand what the artist was doing. “Fontana’s mental operation (which was resolved practically in an instant, in the gesture of cutting the canvas),” Mulas would write, “was far more complex and the concluding gesture only partially revealed it. Seeing a painting of holes, or a painting of cuts, it is easy to imagine Fontana making the cut with a blade or the holes with an awl, but this does not let one understand the operation that is more precise and is not just an operation, but a particular moment, a moment that I understood I had to photograph.”

|

| The Waiting. Lucio Fontana photographed by Ugo Mulas in 1964 |

|

| TheWaiting. Lucio Fontana photographed by Ugo Mulas in 1964 |

|

| Lucio Fontana at the 1966 Venice Biennale |

In addition to the conceptual operation(which has already been discussed here), however, it is also interesting to understand the terms of thetechnical operation, which followed a precise and far from simple procedure (and it is necessary to note the importance of technique for Fontana, although the creative act comes before manual skill: “the technique,” he explained to Carla Lonzi, who later published the interview in her celebrated Self-Portrait, “for us it was the earth, the marble, the bronze, and really you had to know how to use them because you had to model and, in the modeling, you gave all the life, you gave all the form... [...]. Today the techniques are endless, it’s almost a wanting to take advantage of techniques just to get away from the pictorial fact [...]. Technique is important to an artist’s skill, right? Because the artist is already a creator and creates with whatever material, then he practices and perfects it.”). One of the most interesting studies on Lucio Fontana’s technique is the one published in 2012 by art historian Pia Gottschaller, entitled Lucio Fontana. The artist’ s materials, in which all strands of the Italian-Argentine artist’s production are examined in order to investigate the ways in which the final result was achieved. Over a period of ten years, from 1958 to 1968, Fontana made about 1,500 cuts, which thus became the most consistent strand of the artist’s production, the natural extension of the previous holes, and the limit that Fontana himself thought he could not overcome (“I with the cut have invented a formula that I don’t think I can perfect,” he would say. “I have succeeded with this formula in giving the viewer of the painting an impression of spatial calm, of cosmic rigor, of serenity in the infinite.”) During this time, Fontana continued to experiment: on colors, on materials, on the format of the canvases, on the number of cuts, on their arrangement, on their size in relation to the surface. The first two years were the ones most intensely devoted to research: from 1960 onward, the experimentation tapered off and Fontana became comfortable with works bearing one to five cuts on monochromatic canvases.

Making a cut on the canvas involved, meanwhile, a technical challenge: that is, it was necessary to understand how to carve the canvas without decreasing its tension, so that the cut portion would not open excessively, ruining the work irreparably due to the deformations it would undergo (it is not easy to keep a cut canvas flat and perfectly taut, moreover, the edges of the cuts tend to absorb moisture differently and unevenly than the rest of the canvas). And again, the cuts become deformed over time, since at different points the canvas is subjected to different tensions, and the slashes themselves react differently depending on the materials and the manner in which the support was prepared (for example, we know that Fontana abandoned his experiments with ink as early as 1959, because an ink preparation was more delicate and the cutter, as soon as it rested on the surface, left small incisions even before the action of the cut began). In addition, a cut made in a non-decisive manner could have created frayed edges, and further problems could have occurred at the beginning or end of the cut, also depending on the manner and firmness with which the blade would begin or finish etching the surface. Not to mention that all the problems described so far also varied depending on the type of cloth chosen (it is obvious that a coarse-grained cloth would rip in a totally different way than a fine-grained cloth).

In any case, Fontana left no writings about how he made the cuts: Pia Gottschaller’s study relied on the accounts of the only two people who worked in Fontana’s studio, namely the designer Nanda Vigo (Milan, 1936), who collaborated with Fontana mainly on the environments, but also assisted in the realization of his other projects, and the artist Hisachika Takahashi (Tokyo, 1940), who worked with Fontana from 1964 to 1968. Usually Fontana ordered six to eight canvases at a time: probably his main supplier was Colorificio Nord, but according to Enrico Castellani (Castelmassa, 1930 - Celleno, 2017) Fontana perhaps also opted for materials from Colorificio Calcaterra, which also supplied Castellani himself. According to Vigo, Fontana also ordered canvases from the Crespi workshop on Via Brera in Milan, where the more expensive materials came from, although examinations of the works have not revealed major differences between the fabrics, or at least not such as to be able to distinguish their provenance. The artist from Rosario always chose Belgian linen canvas for his works, although the grain of the fabric could vary (from 1959, Fontana preferred medium-grained canvases made of much thicker fabric than those he chose in his early experiments: these characteristics allowed him to create more tension and consequently reduce the opening of gashes). On a few occasions he also used jute cloth, which, however, presented significant tension problems. From the 1959 Spatial Concept in the figure below, it is easy to see what the problems might have been (in this case, less than perfectly stretched canvas creates small lifts near the edges of the slashes).

Before being colored, the canvas was prepared with an application of white paint on both the recto and verso, so that the pictorial matter impregnated the entire surface. The preparation was made with cementite, a high-density varnish invented in 1928 by a Genoese company, Tassani, and which became widely used in the 1950s (so much so that it also became a term used to refer to similar preparations made by other firms) because of its strength and versatility, and alkyd resins (a low-cost material) were used as a binder. The canvas thus prepared was attached to the frame by means of nails alternating with staples that were to keep it in tension. The front of the canvas was then colored: Fontana experimented with various solutions, from oil paint to aniline, although his most famous material ishydropaint, a water-diluted paint usually used to paint the walls of homes, readily available, inexpensive, and ready for use. The choice of water paint, which became preponderant in the later stages of the artist’s career, was due to certain essential characteristics of this material, in particular its tendency to dry quickly and its ability to ensure a smooth surface, such that the lines of the brushstrokes could not be seen.

|

| Lucio Fontana, Spatial Concept. Waiting (1959; aniline, cuts and holes on canvas, 97 x 130 cm; Milan, Fondazione Lucio Fontana), cat. 59 T 1. © Fondazione Lucio Fontana) |

|

| Lucio Fontana, Spatial Concept. Waiting (1959; water paint on canvas, 100 x 81 cm; Rovereto, MART - Museo di Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto, on deposit from private collection), cat. 59 T 38. © Lucio Fontana Foundation |

Having finished the preparation, the time for cutting came. As Mulas’s testimony shows, it could be a long time before Fontana decided how to make the incision. When he proceeded, the artist used a Stanley cutter, which was very sharp, and ran his hand from top to bottom at a moderate speed: this operation required a very steady hand, since a badly carried cut could in no way be corrected, and everything that had been done previously to prepare the support would run the risk of being thwarted. Fontana then had to make a further consideration: that is, he had to choose the exact moment for drying the canvas. In fact, the cut was conducted before the canvas dried completely, because a surface that was too dry would have contracted the canvas, creating problems for the cut. Once the cut was made, Fontana applied strips of sturdy, thick black gauze (which he called “teletta”) to the back so that the wall behind the painting could not be seen. They were adhered with Vinavil glue smeared behind the two edges of the cut, and they also had what we might call a static function, since they reinforced the structure of the work (the gauze in fact blocked the deformation of the edges of the cut). In addition, the blackness of the gauze also had a purely conceptual function (“when I sit in front of one of my cuts, contemplating it,” the artist would have said, “I suddenly feel a great relaxation of the spirit, I feel like a man freed from the slavery of matter, a man who belongs to the vastness of the present and the future”). The edges of the gash were then adjusted by hand so that they took on the characteristic slightly concave shape that distinguishes almost all of Lucio Fontana’s cuts: this was necessarily a manual operation, since the edges, with the cutter’s incision alone, certainly do not end up having the shape we see in the finished work.

Once finished, Fontana would sign the back and often also affix a phrase that referred to memories, moods, and experiences of everyday life: there are, for example, declarations of love to his wife (“I love Teresita,” on the back of the cut identified by the number 60 T 9), circumstances of everyday life (“Martha Jackson came to see me,” 68 T 110, “Tomorrow it will be cold,” 65 T 109), lapidary reflections on the present (“Is it possible that politicians do not understand,” 67 T 102), memoirs (“In 1906 when I arrived in Milan, they were chasing horse-drawn streetcars,” 67 T 107), expressions of grief over the disappearance of his beloved dog Blek (“Blek, goodbye forever,” 67 T 86, “I am still so sad hello Blek,” 67 T 88), and cryptic phrases, almost steeped in mysticism (“I am waiting for the gardener of the soul,” 67 T 70, “I am beginning to be tired of thinking,” 68 T 27). These inscriptions have been interpreted as a stratagem that Fontana had devised to defend his work from forgeries: any calligraphic expertise would surely have established the authenticity of the inscription (defending the artist’s work today is the active Lucio Fontana Foundation, which, in addition to authenticating the works and thus guaranteeing their genuineness, compiles the artist’s general catalog and collaborates in the organization of numerous exhibitions that disseminate his work to the general public). On the other hand, it was rare for Fontana to date the works: probably this feature was due to the fact that, for the artist, his Spatial Concepts had to be located outside of time. Instead, it is quite common to find the title, Spatial Concept or Waiting.

When one of the cuts was finished, Fontana rarely went back to work on it. For example, he could repaint the work to change the color, but this is a very rare occurrence: Gottschaller reports only three cases in which the artist kept the color but changed the hue, and only one in which he opted for a totally different color than the one initially chosen. According to Takahashi’s testimony, Fontana did not touch up the surface even the rare times in which he mistakenly touched it with the handle of the cutter, thus creating a small spot that was smoother and shinier than the rest of the work. He was more likely to change the orientation of the work once it was hung: there are cases of works with inscriptions on the back running in opposite directions, indicating how Fontana probably changed his mind about the direction in which the work was to be displayed. Other similar cases appear in exhibition catalogs: sometimes works can be found turned to one side, and in later catalogs they can be found rotated. The significant fact, Gottschaller points out, is that “for Fontana the orientation of the work was not carved in stone. Especially at the beginning of the cycle of cuts, it seems that Fontana experimented with different ways of achieving balance simply by turning the canvases.” However, it is certain that the artist had discarded the idea of cuts flowing horizontally from the very beginning.

|

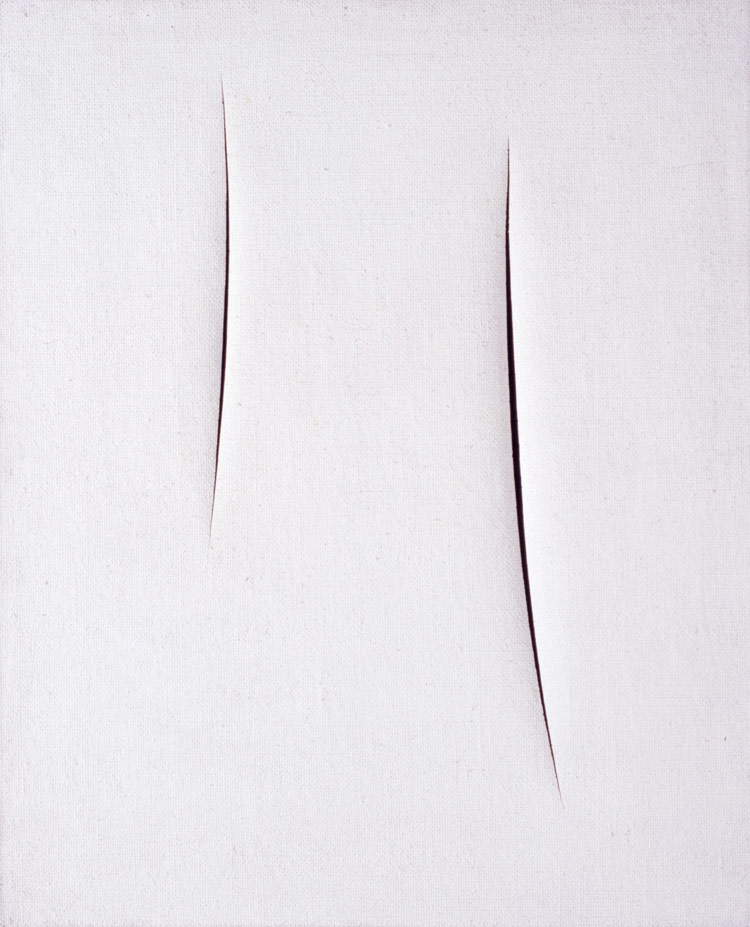

| Lucio Fontana, Spatial Concept. Waiting (1963-1964; watercolor on canvas, 47 x 38.5 cm; Private collection), cat. 63-64 T 18. © Lucio Fontana Foundation |

|

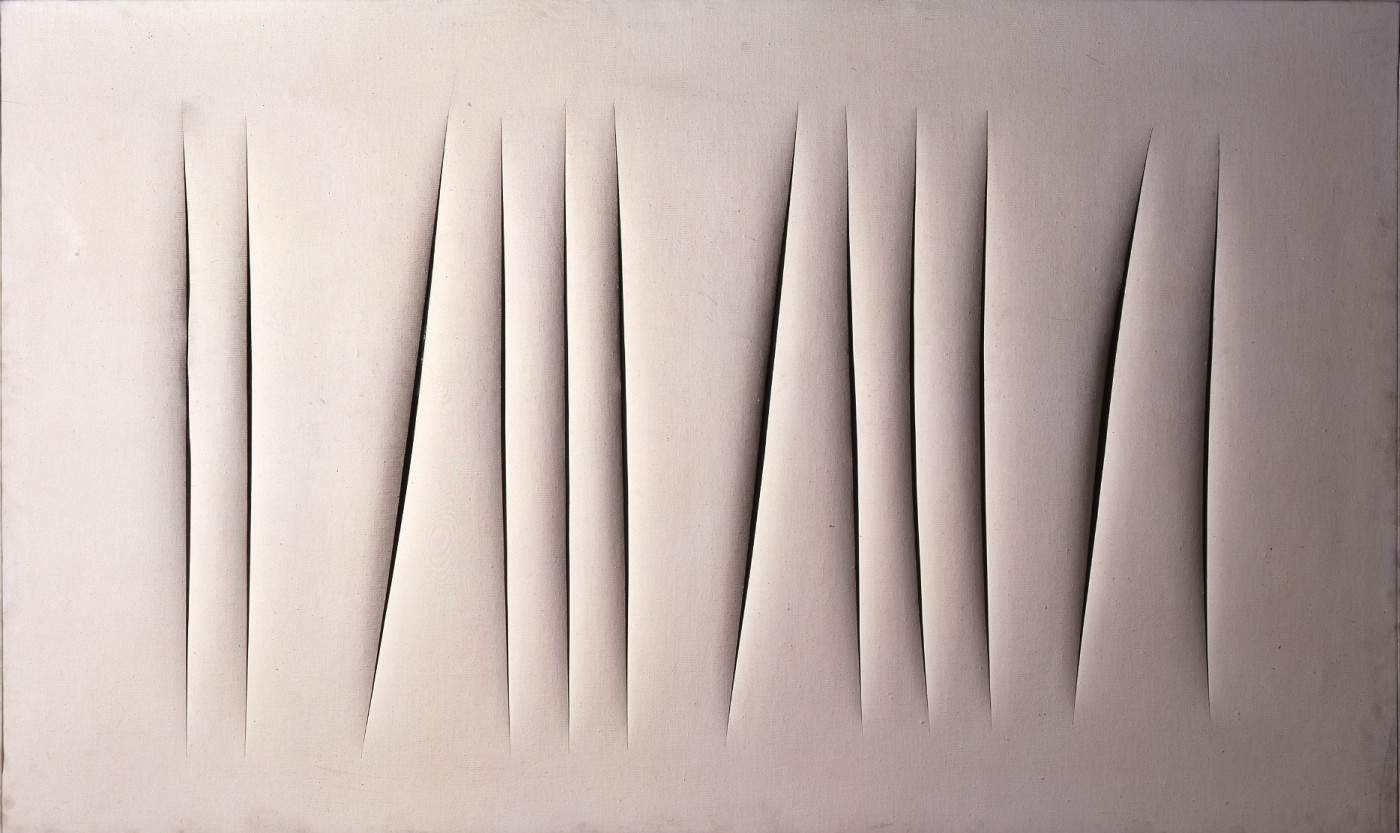

| Lucio Fontana, Spatial Concept. Waiting (1964; cementite on canvas, 190.3 x 115.5 cm; Turin, Galleria d’Arte Moderna). © Lucio Fontana Foundation |

Fontana, throughout the last ten years of his career, from the first to the last cut, did not stop continuing to experiment and seek new solutions for the works for which he is best known, in search of results that were conceptually and aesthetically perfect. In his production we find (and some examples are given here) cuts that are more or less enlarged, more or less curved, oblique or vertical, present alone or in groups having the same dimensions or of different lengths. An apparently trivial, obvious, easy gesture, and one that could be considered within the reach of everyone, required a certain technical skill, an aptitude for research, and great concentration, bordering on the contemplative. Although perhaps, as Pia Gottschaller has noted in reporting the accounts of Takahashi and Getulio Alviani, among others, the truth lies somewhere in between: in particular, Fontana was unlikely to produce a single cut per day, more likely to make small groups of Attese for each working day (up to a maximum of ten, it is believed). And given the volume of cuts that have come down to us, we can establish that Fontana produced an average of one cut every two days (we must then consider that this was not the only strand that occupied the last ten years of his career). And it is Fontana himself, however, who explained that the large number of works was due to the pressing demands of the market: “everyone wants my cuts,” the artist explained in an interview with Giorgio Bocca published in Il Giorno on July 6, 1966, on the sidelines of the thirty-third Venice Biennale where the artist won the Grand International Prize for Painting. The artist confessed to Bocca that for his needs, one cut per month would have been more than enough, but collectors and dealers were begging him constantly for new Spatial Concepts. And he was also fully aware of their value, lamenting the fact that when they cost a few thousand liras, no one wanted them, while they had become a sort of object of desire when their value had begun to touch the millions of liras: and Fontana, of course, watched with amusement as his quotations rose and collectors’ interest in his work increased.

This, however, was a secondary aspect of his work. It is normal that Fontana had made a good profit from his cuts, but that was not the reason why he continued to produce them. The artist was not so much interested in the fact that wealthy collectors could grab his works: he was more concerned that his work be known by as many people as possible, and that it be appreciated. The artist Fausta Squatriti (Milan, 1941), Pia Gottschaller points out in her study, recalled that Fontana, out of his “sense of democracy,” “would also have liked to create an infinity of white cuts (which he thought were the most beautiful) so that everyone could own one.” And, Gottschaller writes further, “he told Takahashi that he would simply be content if his work was seen by many. Alviani explained that Fontana was constantly being asked to exhibit, and that collectors expected to have an assortment to choose from when they came to his studio. But many of those who knew him assert that Fontana continued to be extremely generous, giving away many works to friends and acquaintances.”

Reference Bibliography

- Iria Candela, Emily Braun, Enrico Crispolti (eds.), Lucio Fontana. On the threshold, exhibition catalog (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, January 23 to April 14, 2019), Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019

- Maurizio Vanni (ed.), The Violated Canvas. Fontana, Castellani, Bonalumi, Burri, Scheggi, Simeti, Amadio and the Physical Investigation of the Third Dimension, exhibition catalog (Lucca, Lucca Center for Contemporary Art, March 19 to June 19, 2016), Lu.C.C.A., 2016

- Pia Gottschaller, Lucio Fontana. The artist’s materials, J. Paul Getty Museum Publications, 2012

- Silvia Pegoraro (ed.), Lucio Fontana and his legacy, exhibition catalog (Castelbasso, Borgo Medievale, from July 9 to August 28, 2005), Skira, 2005

- Giorgio Cortenova (ed.), Lucio Fontana. Metafore barocche, exhibition catalog (Verona, Palazzo Forti, October 25, 2002 to March 9, 2003), Marsilio, 2002

- Jole de Sanna, Lucio Fontana: matter, space, concept, Mursia, 1993

- Ugo Mulas, L’attesa, Einaudi, 1973

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.