How Etruscan art influenced twentieth-century art

The Etruscan civilization, with its aura of mystery, fascinating aesthetics and distinctive materials, was a powerful creative stimulus for artists, intellectuals and designers in the 20th century. To this day, many designers continue to be inspired by Etruscan civilization: just looking at recent cases, one need only think of architect Mario Cucinella ’s project for the Rovati Foundation opened in the historic Palazzo Bocconi-Rizzoli-Carraro. The underground rooms, which house the foundation’s Etruscan collection, are inspired by Etruscan tombs with the idea of transporting the visitor with thought to Populonia or Cerveteri. It is precisely to explore these tangencies that the Mart in Rovereto and the Rovati Foundation have organized an exhibition on the theme, Etruschi del Novecento, curated by Lucia Mannini, Anna Mazzanti, Giulio Paolucci and Alessandra Tiddia, with the first stage at the Mart from Dec. 7, 2024 to March 16, 2025, and the second stage at the Rovati Foundation from April 2 to Aug. 3, 2025.

This fascination, fueled by sensational archaeological discoveries such as theApollo of Veio (1916) and fostered by cultural events such as exhibitions and publications, gave rise to a phenomenon defined by art historians as the “Etruscan renaissance.” The visual culture of the short century, through the rediscovery of Etruscan antiquity, found a vibrant and original alternative to classical academicism, embracing an archaic, synthetic and expressionistic aesthetic.

The “Etruscan fever” of the twentieth century

Over the course of the twentieth century, what could be called a true “Etruscomania” broke out, comparable to the first wave of fascination with Etruscan civilization, which occurred in the eighteenth century (at the time it was called “Etruscanism”), and saw among its protagonists such figures as the collector Mario Guarnacci from whose collection derives the founding nucleus of the Guarnacci Museum in Volterra, one of the main existing Etruscan museums, or the archaeologist Giovanni Battista Passeri, one of the leading scholars of Etruscan things at the time. Twentieth-century Etruscomania is evidenced by events such as the Exhibition of Etruscan Art and Civilization (in Milan, at the Palazzo Reale, in 1955, with installations by Luciano Baldessari) and the Etruscan Project (1985), which helped spread knowledge of Etruscan civilization internationally. Leading artists such as Alberto Giacometti, Pablo Picasso, Marino Marini, and Arturo Martini were inspired by Etruscan forms and materials. Etruscan terracottas, bronzes, buccheri, and votive offerings provided cues for a creative reinterpretation that combined modernity and tradition.

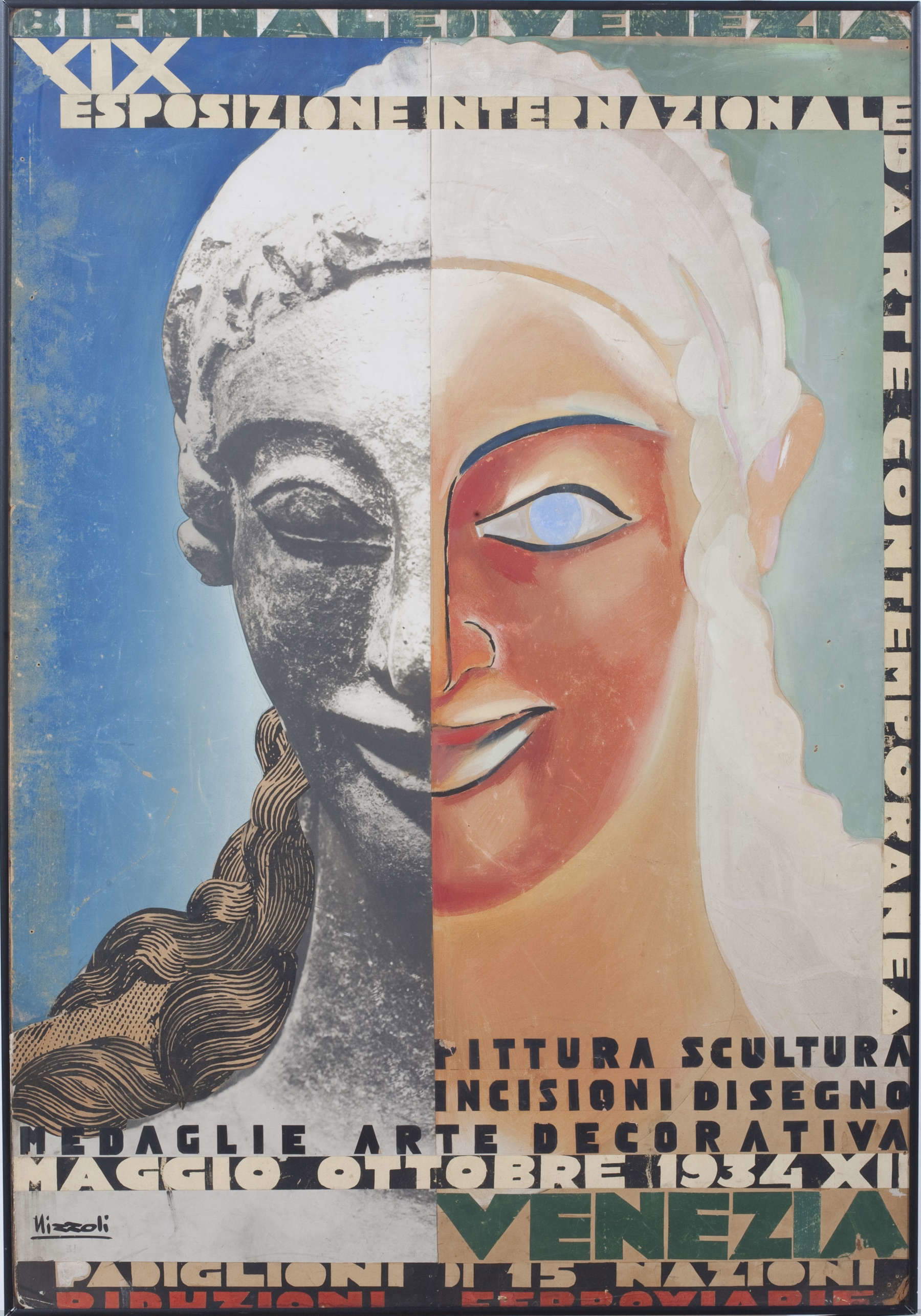

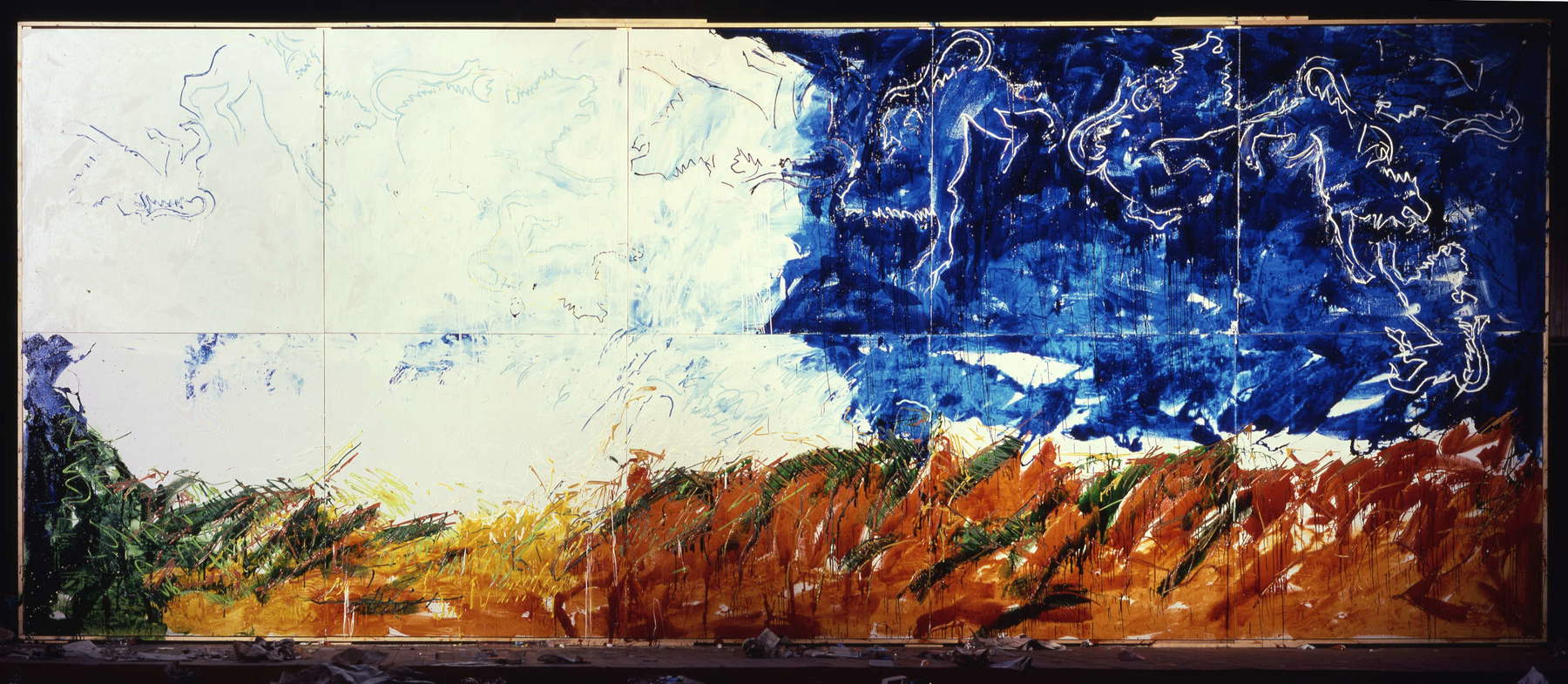

“The influence of Etruscan culture on twentieth-century culture,” explains scholar Anna Mazzanti, “has various moments. It is like a wave has peaks, which retracts and then returns, and in which three significant situations can be identified. One is about a very important, sensational discovery, a group of Templar and terracotta sculptures, the most important example of which is the Apollo of Veio, which generated a first great explosion of Etruscan archaeological culture, to such an extent that professorships, studies, journals of Etruscology and a great visual explosion in the journals were born, which generated the interest of artists.” The Apollo of Veio, with its enigmatic archaic smile, discovered in 1916, became a powerful symbol of this influence and in fact initiated the rediscovery of the Etruscans. The sculpture appeared in art posters and catalogs of the time, representing an ideal point of contact between the expressive power of the ancient and modern stylistic pursuits. The other two important moments according to Mazzanti are precisely the two exhibitions of 1955 and 1985. “The 1955 exhibition,” he explains, “coincides with an evolution of the Studies, thanks to the curator of these exhibitions, Massimo Pallottino, an Etruscologist who systematized all the studies that had developed from the beginning of the 20th century, from the discovery of Veio until the middle of the century, and was able to translate them into an exemplary exhibition, very communicative, and at the same time rigorously scientific, which made an important point.” The 1985 traveling exhibition, on the other hand, was a major traveling exhibition, a review that “had the peculiarity, typical of the 1980s, of having a wide-ranging focus: sociologists, scholars of contemporary arts were involved, so it is interesting to consider that the two main exhibitions, the one at the Archaeological Museum of Florence and the one at the Palazzo degli Innocenti, were dedicated to Etruscan culture and the fortunes of the Etruscans in the contemporary world.” The year 1985, proclaimed “Year of the Etruscans,” was a crucial moment in the rediscovery of Etruscan civilization. During this period, Tuscany was the center of a series of cultural initiatives, culminating in the exhibition Civilization of the Etruscans in Florence. On May 16, 1985, the day of the inauguration of the Florentine exhibition, Mario Schifano, already famous at the time for his capacity for instinctive, immediate representation, gave rise to an artistic performance during which he created a huge painting dedicated to the Chimera of Arezzo, a work found in the 16th century and which already at the time generated a great deal of attention among artists. Schifano, in particular, painted silhouettes of light chimeras, as if they were transported by time: “they took off in flight,” he had this to say, “turning upside down and twirling in the air toward the blinding white of the light on the opposite side, to dissolve like dreams in the morning.”

For many artists of the twentieth century, a visit to the symbolic places of Etruscan civilization was moreover a fundamental stage in their creative formation. Pablo Picasso and Ardengo Soffici, for example, explored Etruscan museums and archaeological sites in search of inspiration, as in a sort of ideal “Grand Tour” of Etruria, which included places such as Volterra, Tarquinia, Cerveteri and Chiusi. Tarquinia’s tomb paintings, Volterra’s alabaster urns, and bronze sculptures such as Arezzo’s Chimera captured the imagination of many, resulting in works of art that reimagined these ancient relics in a contemporary key.

Visual art: from the Etruscans to the avant-garde

The Etruscans were a source of inspiration for artists who sought to break with classical conventions by adopting a more authentic and direct language of expression. Arturo Martini, with his terracotta sculptures, evoked the Etruscan world through synthetic forms and archaic lines. His choice to work with poor materials such as clay drew attention to the human and vulnerable dimension of art. Alberto Giacometti ’s well-known elongated figures reflect his interest in a certain type of Etruscan sculpture (think of theEvening Shadow in Volterra). Another great artist of the 20th century, Giacomo Manzù, was one of the most original interpreters of Etruscan art: the portrait the artist made of his wife Inge is inspired precisely by Etruscan pottery.

Massimo Campigli, influenced by his visit to the Villa Giulia Museum, reworked Etruscan faces in his paintings, evoking the emotional intensity of the funerary figures, giving them those enigmatic, somewhat sardonic smiles often seen in Etruscan art. Michelangelo Pistoletto, with his work L’Etrusco, paid homage to Etruscan sculpture by placing a copy of the Arringatore in front of a mirror-a metaphor for critical reflection on time and identity. Then again, Marino Marini was so taken with Etruscan art that he went so far as to call himself ... an Etruscan himself. Then we cannot forget Pablo Picasso, who just after the war in Vallauris experimented a lot with ceramics. Picasso, in turn, was approached to Etruscan art by his friend Gino Severini, who lived most of his life in Paris: he was from Cortona and therefore well acquainted with Etruscan antiquities (he himself executed some bronzes inspired by the pieces and masterpieces in the Museum of the Etruscan Academy of Cortona). For Picasso, the animal and anthropomorphic forms of Etruscan culture were an ideal cue for his own research on primitive arts. Picasso himself was a reference point for artists who would later work in ceramics inspired by the Etruscans.

And speaking of ceramics: bucchero, a black pottery typical of Etruscan civilization, was reinterpreted by artists such as Duilio Cambellotti in the 1920s and Carlo Alberto Rossi in the 1950s, who experimented with new techniques to create modern works with an archaic soul. Cambellotti in particular was among the artists who most and best worked on bucchero: he appreciated it above all for its plastic, sculptural aspect. Terracotta, on the other hand, became the material of choice for sculptors such as Arturo Martini and Marino Marini, who appreciated its ability to evoke imperfect beauty and human frailty. These materials, with their connection to earth and time, made tangible the dialogue between past and present.

Design and applied arts in the sign of the Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization also left an indelible mark in the design and applied arts of the twentieth century. The influence can be assessed under two different profiles: that of material and that of form. “One of the most identifying materials of Etruscan culture,” explains Lucia Mannini, "is bucchero, a ceramic that undergoes a particular firing process that makes it black both on the surface and in fracture. This very special technique, adopted by the Etruscans and which scholars throughout the 20th century tried to discover and decipher, had meanwhile been discovered and adopted by many artists: among the first in Rome, Francesco Randone, as early as the end of the 19th century, rediscovered this particular process ... and kept it secret. The recipe and firing methods are transmitted only to his daughters, who make, together with their father (in a resounding context, within the Aurelian walls), objects that are inspired, effectively even in form, by Etruscan art: they are, for example, rhytons (ed.: containers for liquids) with anthropomorphic animal forms, or lanterns, in or in any case very light objects that sought from bucchero above all the lightness, delicacy and refinement of the decorations."

Gio Ponti, one of Italy’s greatest designers, was inspired by Etruscan cistes and askos (small two-mouthed vases for oil, with anthropomorphic or zoomorphic shapes) to create everyday objects that blended functionality and archaic beauty. The great designer was attracted to both materials and forms, particularly those of vases but also those of the anatomical sculptures that the Etruscans offered to the gods. In the field of jewelry, artists such as Arnaldo Pomodoro and Afro Basaldella reinterpreted the techniques and motifs of Etruscan goldsmithing, using granulation to create ornaments that evoked ancient relics. And always looking to the forms of Etruscan art. “These are objects,” Mannini explains, referring to Etruscan art and applied arts, “that are rediscovered and ’sucked in’ by artists from the 1920s until especially after World War II, the 1950s: this is no coincidence, because it is a time when, simultaneously with the revival of Etruscan art, the applied arts are also being resurrected and reborn in Italy, and therefore there is a need to provide new models and new forms. And where do they go to look for them? No longer in art, not only perhaps in Renaissance art or in established cultures, but they go to experiment and look in unusual places, exploring for example archaeological museums.” Gio Ponti himself, “just arrived at the qualification of artistic director of the Richard Ginori manufactory, to propose new objects to be presented at major exhibition events we know that he frequents the archaeological museums of Florence and Rome. And like him, for example, Guido Andloviz, who would be said today to be a kind of competitor, at the head of a ceramic factory in Laveno, the Società Ceramica Italiana.”

Fashion, too, embraced the Etruscan legacy. Fernanda Gattinoni, with her 1956 “Linea Etrusca,” celebrated the beauty and mystery of Etruscan women through clothes that echoed the stylistic details of the sculpted figures. There has been no shortage of examples in jewelry, either: several artists, such as Fausto Melotti, have created jewelry inspired by Etruscan art, and the well-known Aretine brand UnoAerre, in 1985, conducted some experiments, studying material from the Archaeological Museum in Florence, on the Etruscan techniques of granulation and dusting to try to reproduce them.

The influence of the Etruscans in twentieth-century art demonstrates the pervasive power of ancient cultures in shaping modern aesthetics. Artists of the short century, embracing the simplicity and expressiveness of the Etruscans, found fertile ground to explore new forms of creativity.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.