How did the Etruscans dress? Fashion and clothing in Tuscany 2,600 years ago

Colorful fabrics in light and bright hues and with strong contrasts, cuts in the most varied fashions, a marked sense of elegance, a taste that favored refinement, whimsy, and fantasy: these are the most obvious characteristics of Etruscan fashion. Few other ancient civilizations were able to develop clothing as varied and lively as that of the Etruscans, who, when they dressed, rejected the sobriety of the Greeks and theausterity of the Romans and, on the contrary, showed an appreciation for original and colorful, often extravagant clothing. To observe the Etruscan artifacts that have come down to us is to enter the colorful world of a civilization in which wealth was widespread, which loved luxury, which developed an open mentality, which granted women an independence and freedom unknown at other cultures, and where even the lowest strata of the population (and even slaves), in all likelihood, liked to dress in more beautiful and richer clothes than those that, in other places, would be considered suitable for their status. An analysis of the fashion of the time thus reveals a true Etruscan look, made up of clothes in different patterns or white and elegant but with great attention to detail, as well as cloaks with rounded cuts, pointed shoes, precious and extravagant jewelry worn even by men-a look that was also able to inspire several contemporary designers.

There are several features that make Etruscan fashion unique and particularly modern. Beginning with the fact that, especially in archaic times, women often wore typically male clothing: these were mostly togas and capes, but it was also true of the so-called calcei repandi, the pointed boots that represent the most distinctive Etruscan footwear. This custom probably arose out of practical needs, related to the climate of northern Italy, which was harsher than that of Greece, and therefore forced women to wear the same heavy cloth cloaks worn by men in order to shelter from the weather. And again because of the climate, Etruscan fashion comes to devise a large number of garments of the most varied shapes: another characteristic of Etruscan fashion is its great variety, which is unmatched by other contemporary civilizations. Moreover, as was the case with Greek fashion, decoration in Etruscan fashion had a purely ornamental character: the opposite of Roman fashion, which had developed decoration of a symbolic character. Again, for the Etruscans the choice of clothing was not rigidly linked to the social class to which they belonged, as was the case with the Romans: Etruscan women and men usually chose their clothes freely and according to their individual taste. The fashion of Tuscany two thousand six hundred years ago thus tells the story of an evolved society, where the taste for fine dress cuts across social classes.

There are several works that can offer us particularly eloquent evidence. Walking through the halls of the Archaeological Museum of Florence, one cannot help but notice the sarcophagus of Larthia Seianti, one of the most interesting works in the museum. It is a masterpiece of Etruscan sculpture from Chiusi: a terracotta sarcophagus with the case beautifully decorated with a frieze of floral motifs, and surmounted by the portrait of Larthia, a lady belonging to a wealthy family of Chiusi in the second century B.C. And besides being a work of art of unquestionable quality, the portrait of Larthia is also a very important document on the fashion and customs of the Etruscans (not least because, moreover, much of the original polychromy has been preserved: the sarcophagus, in fact, was painted in color). The woman is lying on her kline, the peculiar bed on which the ancients reclined during banquets, and is caught in the act of mirroring herself, while with one hand she removes the veil that encircles her head. The jewelry she wears (disc earrings with gaudy gold pendants, bracelets that are also gold, anarmilla, that is, the bracelet that was used to be worn on the biceps, a diadem, and a Medusa’s head pendant on her neckline) indicate her high social status. Her dress, on the other hand, denotes the elegant taste of Etruscan women.

|

| Sarcophagus of Larthia Seianti (150-130 BC; polychrome terracotta, 105 x 164 x 54 cm; Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Larthia Seianti’s portrait. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

This is a white tunic, with three vertical violet bands, cinched at the waist by a belt decorated with studs. It has a V-neckline, emphasized by as many violet borders, and goes down to the legs to leave only the feet uncovered. This tunic has a specific name: it is called a chiton and is a Greek-derived garment. Larthia wears a variant of it with short sleeves, but the chiton can also be sleeveless (it should be emphasized that it was an all-weather garment: they were made of wool or cooler linen for the warmer seasons) and, as in the case of the Chiusian lady, the task of covering the shoulders is entrusted to a small cape, light or heavy depending on the season, which can also cover the head. However, the cape is a rather simple garment, which is worn by simply putting it over the shoulders and dropping it straight down so that it forms a rectangle over the shoulders. The short cape is called himation, is also used by men, and is a Greek-derived garment. In many cases, the cape is fastened on both shoulders by means of buttons that may also be finely decorated: the Etruscans could rely on a very fine art of jewelry.

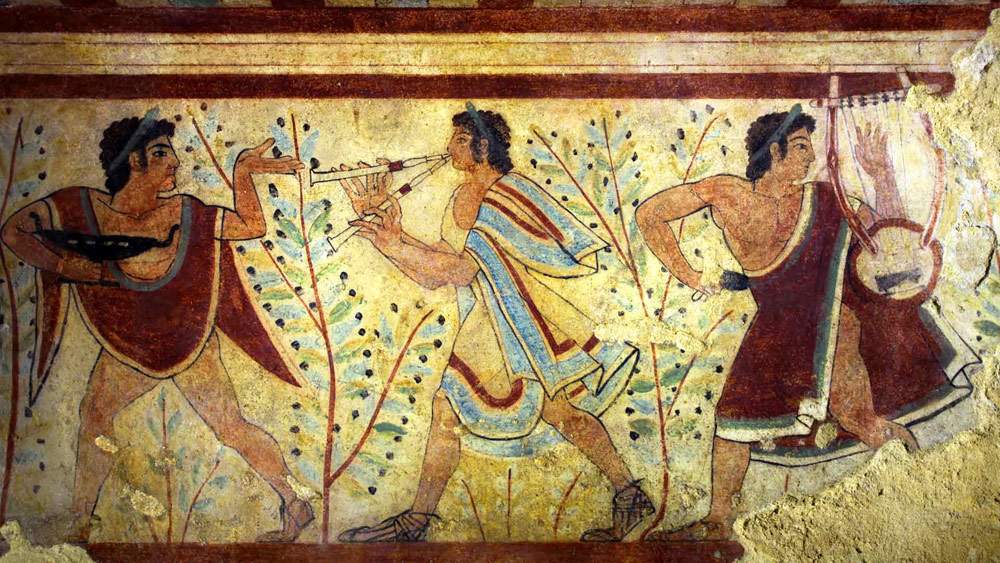

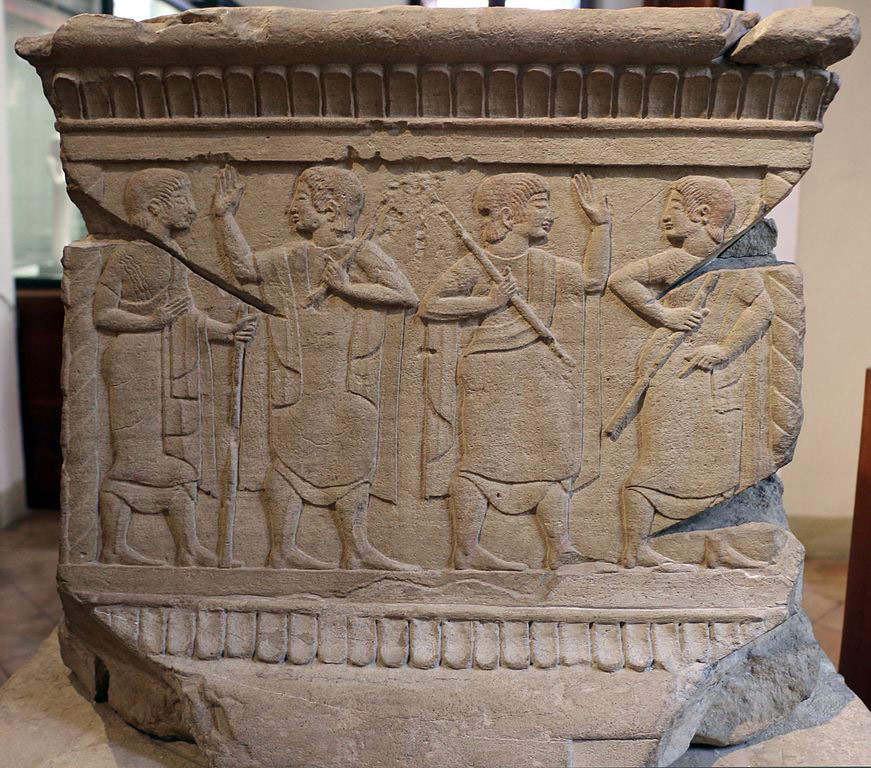

Men also wore the chiton, but it differed from the female version. Also at the Archaeological Museum in Florence we find the stele of Larth Tharnie, a man holding a knife and wearing a three-quarter length chiton, which reaches about knee height (the work can be dated to between 550 and 540 B.C: a time frame that roughly corresponds with the period when Ionian-derived garments, the same garments also worn by Larthia Seianti, were introduced from Greece and arrived in the lands of the Etruscans in the mid-sixth century BCE). Another type of men’s chiton is the one that is short above the knee: in the reliefs that decorate Etruscan urns with a wide variety of scenes, a great many figures are clad in this particular garment, which is fastened at the waist with a belt, so that the lower part appears to form a kind of skirt. Also, typical of men’s clothing (but often worn by women as well) is the tebenna: this is a long cloak, which is worn over the chiton and can be stopped over both shoulders and then allowed to fall straight down, or stopped asymmetrically over one shoulder only. The tebenna is, moreover, the garment from which the Roman toga originated: the tebenna, in fact, can also be worn without a chiton. In the bronze statuette depicting the god Vertumno, which is also preserved in the Archaeological Museum in Florence, we can see how the deity who presided over the changes of seasons for the Etruscans is depicted wearing a short-sleeved chiton and a tebenna stopped at the left shoulder. Then there was another way of wearing the tebenna, much more informal: with the ends brought back over the shoulders and allowed to fall back on the back: we notice this well by observing a character in the frescoes of the Tomb of the Leopards in Tarquinia. Another type of cloak is the chlaina: of varying length, it can reach just beyond the shoulders but in some cases to below the knees, and is a typically male garment. We have examples of it in the Chiusi cippus, where we see some figures wearing it: it falls both front and back (it was worn as one would wear a poncho today) and is semicircular in shape.

|

| Left: Stele of Larth Tharnies (c. 550-540 BCE; stone, height 188 cm; Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale). Right: Vertumno (c. 500 B.C.; bronze, height 27.5 cm; Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale) |

|

| One of the frescoes in the tomb of the Leopards (473 BC). |

|

| Cippo from Chiusi (c. 500-480 BC; stone; Rome, Museo di Scultura Antica Giovanni Barracco). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Figurine of female bidder (5th century BC; bronze; Arezzo, Museo Archeologico Nazionale Gaio Cilnio Mecenate). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

The clothes seen so far begin to appear in Etruscan fashion from, roughly, the middle of the sixth century BCE, under the influence of Greek fashion. The Etruscologist Larissa Bonfante has proposed to divide the history of Etruscan fashion into four main phases, roughly corresponding to the phases of Etruscan art: an Orientalizing period (roughly from 650 to 550 BCE), an Ionic period (until about 475 BCE), a Classical period (until about 300 BCE), and a Hellenistic period (until the end of Etruscan independence, in the first century BCE). From the Ionian period onward, characteristics would develop that remained later typical of Etruscan clothing, but in each of the phases its own peculiarities can be identified. For example, the custom of decorating chitons with tassels, bows or buttons on the shoulders is from the Classical period (Vertumno himself, on the right shoulder of his short-sleeved chiton, wears a long fabric bow), and through the different epochs the ways of wearing them change (typical of the Hellenistic period is the female custom of tightening the chiton with a belt just below the breast: this is clearly seen in theurn of the lady of Perugia, preserved in the National Archaeological Museum in Siena). And again, depending on how fashions evolved, certain fashions became more successful than others (for example, during the Hellenistic period the sleeveless chiton became established, or was fastened with pins so as to leave the arms uncovered). During the first phase, however, clothing turns out to be quite different, with garments that fashion will dictate to be abandoned when Etruscan culture is influenced by Greek culture.

Women used to wear long tunics, also made of different fabrics, over which they wore jackets, bodices or sweaters, variously decorated (at the Archaeological Museum of Arezzo we find a votive statuette where we see a woman dressed in this way), while men, especially in archaic times, wore a particular loincloth that can reach almost to the knees and is worn as if it were a short pant. It is stopped at the waist by belts that can take a variety of shapes: an example of this particular loincloth is what we see in statues A and B from the Casa Nocera necropolis in Casale Marittimo, which are also now in the National Archaeological Museum in Florence. For all, then, it is customary to wear cloaks, which are also richly decorated with various patterns: the absolute most common decoration, however, is checkered or lozenge, and at this stage the garments are brightly colored, of oriental derivation. Several Tuscan museums preserve archaic bronzes in which the patterning decorating the cloaks is suggested by the artist’s engravings on the surface of the bronze. Clothes of this type survive especially even after the sixth century in northern Italy, in areas less subject to contact with Greek civilizations.

Still looking at the works in the Archaeological Museum in Florence, we note that both Vertumno and Larth Tharnie wear another Ionian-derived garment such as the chiton: the aforementioned pointed boots called calcei repandi (literally “curved footwear,” due to the fact that the toe is curved backwards), one of the most typical and easily recognizable garments ofEtruscan clothing, also of Eastern origin. They are tightened around the ankle with laces or belts. There is also no shortage of shoes of different styles, low and without toes, fastened with laces, or, for the summer season, sandals of different shapes and sizes, such as those worn by Larthia in the Florentine sarcophagus.

|

| Urn of the Lady of Perugia (late 3rd-early 2nd century B.C.; Siena, Museo Archeologico Nazionale). Ph. Credit José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro |

|

| Statues A and B from the Casa Nocera necropolis at Casale Marittimo (early decades of the 7th century BC; shell limestone; Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte (A) and Francesco Bini (B) |

|

| Anthropomorphic votive statuettes (ca. 650 BC; bronze; Volterra, Museo Etrusco Guarnacci). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Female figurines (late 7th century BC; bucchero with wheel-impressed decoration; Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

Etruscan fashion would later be destined to l’influence Roman fashion, although as the two cultures began to meet, the Romans rejected the main distinguishing feature of Etruscan clothing: a taste for luxury. The Etruscans, in fact, had achieved high levels of affluence by the seventh century B.C.E.: the cities of northern Italy derived their wealth from mining and metalworking, while the more southern cities, those just north of Rome, flourished through trade, and sophistication and elegance in dress was the most immediate way of communicating their prosperity. The comforts and luxuries with which the Etruscans surrounded themselves thus became a cause for criticism by Greek and Roman contemporaries: the Romans of the early centuries, in particular, rejected these customs of the Etruscans because they believed that luxury corrupted spirits, and the Etruscans, especially in the Republican era, became a negative term of comparison. A Greek observer such as Diodorus Siculus, a contemporary of Julius Caesar and Julius Caesar, writes in his Bibliotecha historica (quoted here in Marta Zorat’s translation), reporting the impressions of his older contemporary Posidonius, a philosopher of the Stoic school, that the Etruscans “prepare sumptuous tables twice a day and all other things appropriate to excessive luxury, setting up beds with colorful linens and embroidery, silver cups of various kinds, and have ready at their disposal no small number of servants to serve them, some of whom are of extraordinary loveliness, while others are adorned with robes more sumptuous than would befit their condition of slavery. By them have special dwellings, and of various kinds, not only the magistrates, but also the majority of men of free condition. In general, they have now lost that prowess which their ancestors sought to emulate from ancient times, and since they spend their lives in drinking and amusements that are not for men, it is not illogical that they have lost the celebrity of their fathers in the activity of war.” And if Strabo asserts that the Romans knew luxury when they subjugated the Etruscans, other authors such as Plato and Theopompus take aim at Etruscan customs, which they say reflected an excessive laxity in the customs of the peoples who inhabited Tuscany and neighboring regions in ancient times. All this, however, would not have prevented the Romans from adopting certain Etruscan garments, adapting them to their taste: tunics, togas and cloaks, purged of excesses, would later be introduced into Roman dress, in the fashions that later became part of the collective imagination.

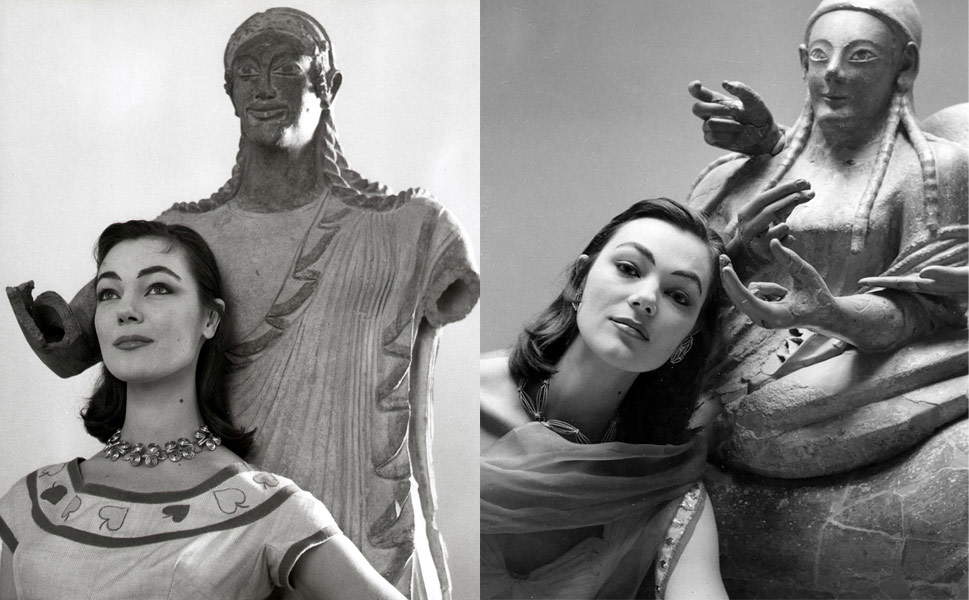

And even today, Etruscan clothing continues to inspire the creations of leading fashion ateliers. In 2013, the fashion house Gucci presented, for its spring-summer collection, a reinterpretation of the Etruscan chiton, foot-length, with a wide V-neck, and with wide sleeves to simulate a himation. The year before, the Marni house had been inspired by the tebenna to design a women’s coat narrow at the waist, with openings at sleeve height, so that it took on the shape of an ancient Etruscan cloak. The interest in Etruscan fashion also applies to men: Custo, also in 2013, proposed a line of men’s cloaks quite similar to those worn by our ancestors, which the models wore over eccentric suits. And going even further back in time, in the 1950s, Fernanda Gattinoni produced a collection entitled Etrusca, making her sources of inspiration obvious (the collection would later be publicized through a photographic campaign that saw models posing together with some important masterpieces of Etruscan art in the National Museum of Villa Giulia in Rome, such as the Apollo of Veio and the Sarcophagus of the Spouses). Etruscan fashion, in certain forms, thus continues to survive... !

|

| The designs of Gucci and Marni |

|

| Custo’s capes |

|

| Gattinoni’s images at the National Museum of Villa Giulia |

Reference bibliography

- Giovannangelo Camporeale, The Etruscans. History and Civilization, UTET, 2015 (fourth edition)

- Richard De Puma, Etruscan Art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Yale University Press, 2013

- Jean-Marc Irollo, The Etruscans: at the origins of our civilization, Daedalus Editions, 2008

- Giuseppe Della Fina, Etruscans: everyday life, L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2005

- Antonia Rallo (ed.), Le Donne in Etruria, L’Erma di Bretschneider, 1989

- Larissa Bonfante, Etruscan Dress, John Hopkins University Press, 1979

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.