Hitler's relationship with the arts, versus modern and "degenerate" art

I am convinced that the work of great statesmen and military leaders always resides in the field of art

Hitler, Mein Kampf

Adolf Hitler (Braunanu am Inn, 1899 - Berlin, 1945) is among the most controversial protagonists of the history of the last century, whose imprint still affects political, economic and social dynamics in Europe and throughout the world. The figure has been much discussed and widely analyzed and studied paying particular attention to his ethical, moral, philosophical and political dimensions. Yet, he is usually silent about the relationship between the Führer and art, not adequately considering his passion for art, his artistic background, and his considerations of painting, sculpture, collecting, and museums.

In support of this thesis, the 2018 documentary Hitler v. Picasso and the Others made by Claudio Poli reconstructs the Führer’s relationship with this discipline not by taking into consideration his artistic side, nor his conception of art, but by focusing on the legitimate demands of the owners, mainly Jews, looted of their works by the regime in force in the 1930s. A closer reading of this sensibility of his should suggest a reflection on how he managed to enslave art to his ideology, making it an integral and relevant part of his political propaganda.

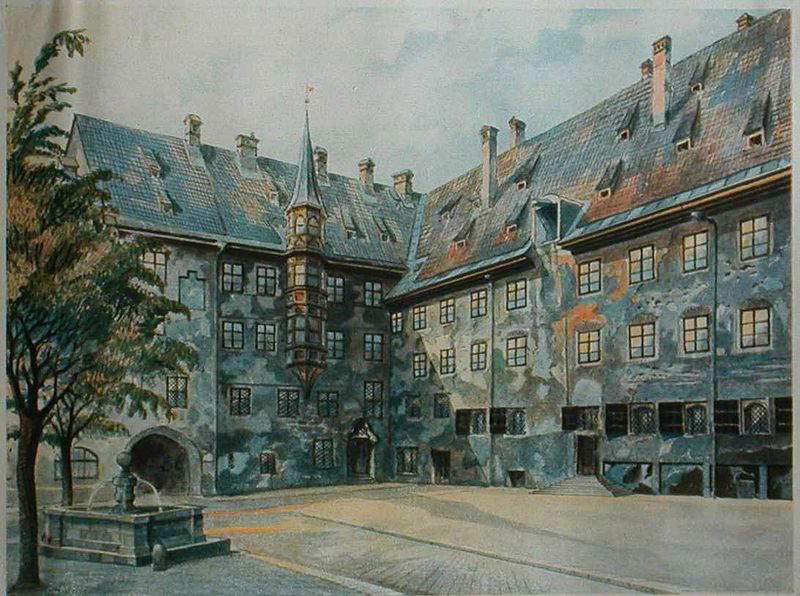

The schematic and rigid line of his works, which made them more like architectural plans than vedutistic works, cost him at a young age two consecutive rejections from theAcademy of Fine Arts in Vienna. The repeated refusals brought him closer to politics: first by following the current of thought of Adolf Lanz’s “anti-Semitic league,” and then by actively engaging in political life, first joining the German Workers’ Party in Munich and soon rising to the highest echelon.

|

| Adolf Hitler, Der alte Hof (1914; watercolor; Washington, United States Army Center of Military History) |

|

| Adolf Hitler, Vase of Flowers (ca. 1912; watercolor, 27 x 34.3 cm; Private Collection) |

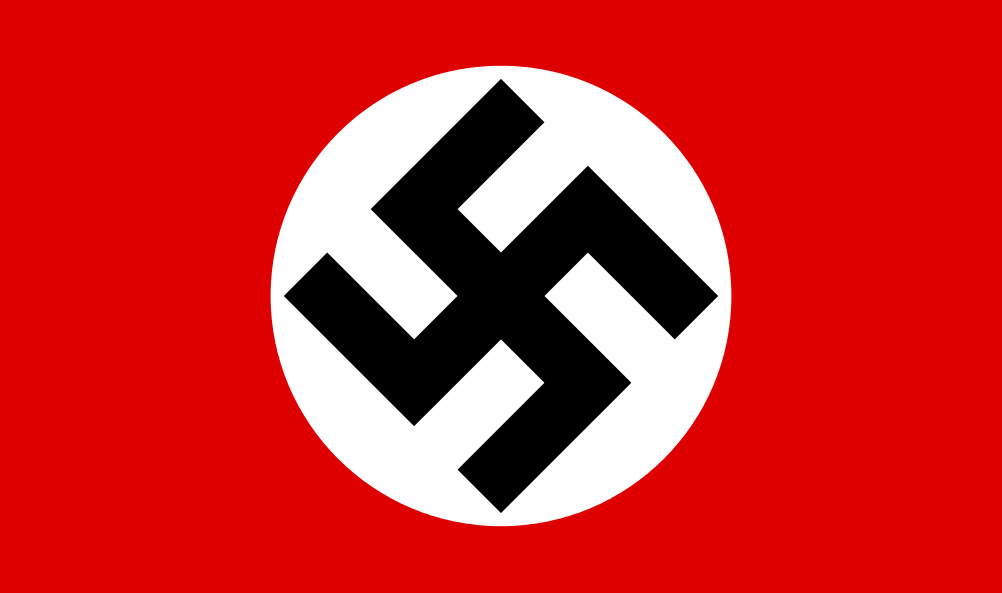

Sensing the emotional potential of the symbols included in works of art, he made use of them and using his experiences in art and his own aesthetic ability to devise appropriate political iconography he focused on theuse of color, with a result that still shakes the world’s imagination today. By his own hand are the changes that made the swastika the quintessential emblem of Nazism. A symbol already known in antiquity, especially in the East where it was connoted with religious meaning and auspiciousness. The swastika in Eurasia was linked to astrology, and taken as a signifier of the sun and more generally of the universe, an iconography taken up in the succession of centuries. In medieval times, for example, it can be seen placed above the head of a Jew, perhaps a moneylender or merchant (because of the typical attire) in a 13th-century miniature belonging to the Cantigas de Santa Maria of Alfonso X, called the Wise.

The swastika, which was already in use in southern Germany as a representative sign of the right, after the Führer’s contribution, reverted to right orientation, rotated 45 degrees clockwise and restored of its original colors, to each of which the not-yet-dictator attributed a peculiar meaning: blood red to establish communication with the masses through the hue most congenial to them, white as a symbol of the nationalistic idea, and black as a demagogic color to exalt the Aryan race in a powerful effective and evocative combination. Hitler’s innate sense of theater (so much so that it has been referred to as Hitler’s theater-cracy) manifested itself through the skillful adoption of lighting, music, and many other technical devices that were used extensively in organizing rallies and public appearances. Even Bertolt Brecht noticed this, who within Gesammelte werke 18 dedicated to him three verses tinged with bitter irony, but underscoring this decisive skill of his: “his virtuoso use of light / is no different / from his virtuoso use of the truncheon.”

|

| Adolf Hitler wears the swastika sash |

|

| The flag of Nazi Germany |

Hitler claimed thatmodernist, i.e., avant-garde art, corrupted society. Thus anyone who supported such art, in this case the fringe of Jewish intellectuals, was at the root of the unraveling of society. And from here it is particularly clear how art, too, was a tool to tare strength to Nazi ideology. For the Führer, modernism was intolerable as provocative, enigmatic, cynical, and uncomfortable: the purpose of art was to be an escape from pain, not a confrontation with it. The German leader strenuously attempted to establish aregime art because he was fully aware of the reach of artistic expression on the masses, an idea inspired by Platonic thought, which theorizes that art and society are enlivened by similar forces and that the former not only reflects the agitation of the latter, but promotes it.

One of Hitler’s main goals was toelevate German culture to exquisite heights, for the realization of which art was necessary. This meant drastically limiting foreign influences, encouraging exhibitions of German painters and sculptors and performances by German orchestras and companies abroad so that the great achievements of Germanic Aryan culture would be evident to the European and more generally to the international consensus. Art thus became a state affair.

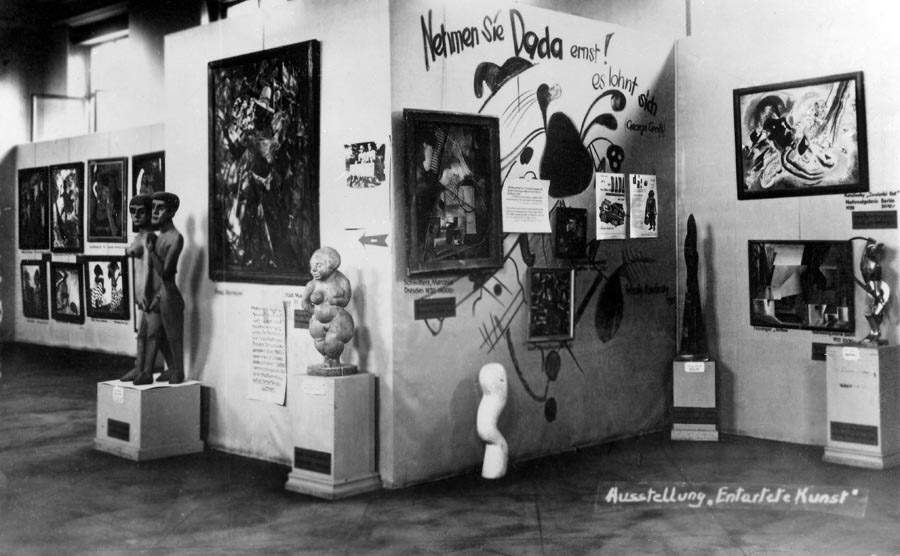

In 1933 party officials got rid of previous museum directors and curators and replaced them with persons recognized by the party as suitable for political views and not for reasons related to their skills and knowledge in the arts. In this way, control of exhibitions was absolute and assured, and as a result modern art collections were commandeered. In support of these positions-which favored and advocated the idea that avant-garde art was wrong and to be eliminated-exhibitions such as the "Schandausstellungen“ (Exhibitions of theAbomination) in 1933 and ”Schreckenskammer der Kunst" (The Chamber of Horrors of Art) in 1935 in cities such as, for example, Dresden and Stuttgart (“Horrible examples of Bolshevik art have been brought to my attention. I now intend to act. [...]. I want to organize an exhibition in Berlin on the art of the period of decadence. So that people can see it and learn to recognize it,” Joseph Göbbels).

A truly disturbing figure was that of propaganda minister Joseph Göbbels (Rheydt, 1897 - Berlin, 1945), who had espoused in every way the attitude of his leader and who moved strictly and fiercely toward art considered degenerate. Theentartete Kunst exhibition was also organized in Munich jointly with the Great German Art Exhibition in the new Art House, the result of a clever move, to show the caesura between art and non-art. The opening took place on July 19, 1937, and the 650 works by 112 degenerate artists (including George Grosz, Emil Nolde, Pail Klee, Gustav Klimt, Otto Dix, and Egon Schiele) were displayed in such a way as to be drastically ridiculed. Paintings were piled up in such a way as to make the walls that housed them confusing. The works were labeled with slogans in keeping with the denigrating method pursued such as, “madness becomes method” or “nature as seen by sick minds.” It was a record-breaking exhibition: it welcomed one million visitors in the first month alone and more than double that number in the next six, encouraged also by the free admission imposed by Hitler. Between ’38 and ’41, in a tour that touched twelve cities, it garnered equally substantial numbers, remaining to this day the most visited in history.

In the same year, in the same city, on the same street, but on the opposite side, the House of German Art opened its doors with the first major annual German art exhibition, Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung. By contrast, the works present were to proclaim and portray grandeur, beauty and prosperity, without ever resorting to those signs declared decadent, to which was also ascribed the cult of the primitive, proper to a part of modern art and evaluated not as an expression of a naive soul, but as a projection of a corrupt and diseased “future.”

|

| The audience in line to enter the Entartete Kunst exhibition in Munich |

|

| Hall of the Entartete Kunst exhibition in Munich |

|

| Hall of the Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung |

Not surprisingly, genre painting fell within the canons embraced by the party: the landscape, the peasant, the hunter, the mother ... a world of substance inhabited by exemplary figures, in an attempt to return to being the grand and universally generalized expression of the noble and heroic will of the whole people. Everything that fell within the National Socialist parameters of dignity of the human condition was reproduced with a system of allegories linking the landscape to the homeland; the human body and the nude to the representation of life and the vigor of good blood, acquiring a value not only biological, but opening up to a signal of individual rebirth, of an entire people and its spirit.

A vision well represented by the paintings of Arno Breker, characterized by the cult of the body, racial unity and military strength. The same applies to works by others, such as Adolf Ziegler, Adolf Wissel, and Hector Erler. It would have to wait until the end of the Third Reich to see modern art fully rehabilitated with Documenta 1 in 1955, conceived by Arnold Bolde and featuring 148 artists, including Max Ernst, Giacomo Balla, Jean Arp, Otto Dix, and Fernard Léger. The goal was not so much to present art produced in the 20th century as to unveil the roots of contemporary art in all its dimensions and to bring the avant-garde, vilified and banned by the National Socialist regime, back to Germany.

Essential to understanding the climate in which Documenta opens is to consider that just a month earlier there had been the declaration of full sovereignty of the Federal Republic of Germany and its entry into NATO and the signing of the Warsaw Pact by the Soviet bloc countries. With its 130.000 visitors in the Museum Fridericianum in Kassel, gutted by the bombings of the war conflict, Documenta 1 became the theater through which to also rethink the museum structure and the concept of exhibition, still relevant today and reproposed in the various editions of Documenta and the biennial artart present, by now, in almost every city (“The museum must introduce people to a special world, in which the works of the dead converse with the gazes of the living, in a lasting and fruitful confrontation,” Roberto Peregalli).

|

| Entrance to Documenta 1 at the Fridericianum |

|

| A room from Documenta 1 in 1955 |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.