On June 18, 1815, Napoleon was defeated by the Duke of Wellington at the end of a fierce confrontation that pitted France against the Seventh Coalition. In history, the Battle of Waterloo is considered one of the watershed events between different eras: the Napoleonic age ended, the Restoration era began. For art history, the end of the age of Napoleon meant the return to their countries of origin of many works of art that had been requisitioned by the French armies at the time of the occupation. Restitution began to be discussed as early as the weeks following Napoleon’s first abdication on April 6, 1814: although the Treaty of Paris, signed on May 30, 1814 between defeated France and the member states of the Sixth Coalition, did not provide for the return of works resulting from Napoleon’s spoliations, the possibility had nevertheless been considered by the King of France, Louis XVIII, who decided to return works that had not been displayed in French museums, except for the collection of the Duke of Brunswick, from whom, after the Third Coalition war, some eighty works were taken. Louis XVIII returned almost all of them to him by way of thanks for having welcomed him to Hanover during his exile.

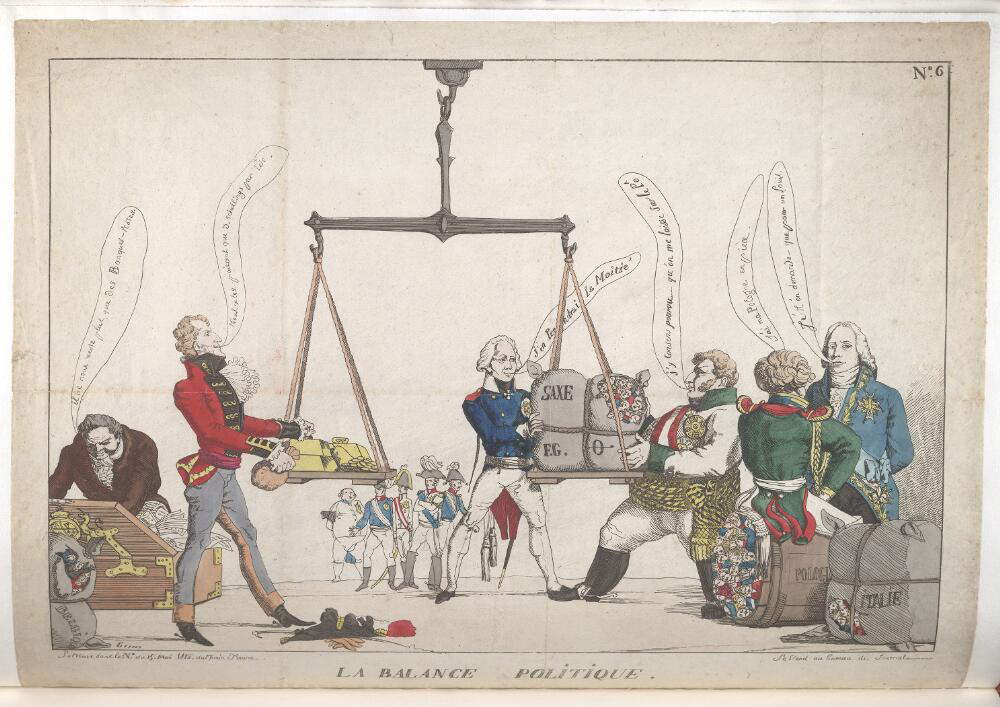

In essence, the restitutions had already begun, albeit very timidly: however, it took until the end of the Congress of Vienna, which ended on June 9, 1815, for the matter to become a subject of debate and contention, although in the end no adequate legal framework was defined to regulate the subject of the repatriation of works. The subject was already sensitive at the time, however, and a heated debate arose over the returns anyway: even among the winners there were those who were skeptical about whether the works should be returned from the Louvre to their countries of origin. One of the arguments was the unwillingness to destroy what had become one of the most spectacular art collections in the world: even, it seems, the German commissioners in charge of the returns of their works had been uncomfortable with the idea of devastating that great universal museum project that the French had dreamed of. Then there were those who proposed leaving it up to the original owners to decide whether to claim the works or to sell them to the French at a fair price, there were those who proposed exchanging the works seized by Napoleon for French works, and there were those who opposed legal and juridical arguments. On the other side, however, there were also states that, even before the end of the war that would spell the final end of Napoleon, had made formal requests for restitution, or had published inventories of objects requisitioned by the French. Louis XVIII himself, however, proved little sympathetic to the requests, and the initial position of the new Bourbon administration of France was not to return the works as they were deemed, following Napoleon’s wars of conquest, to be French property (“The glory of the French army,” Louis XVIII said in a speech to Parliament on June 4, 1814, “has not been stained; the monuments of its valor remain, and the masterpieces of the arts belong to us from this moment with a right stronger than the right of war.”) a position that was even supported by the United Kingdom, at least initially, and Russia. Both the United Kingdom and Russia (which would later remain the sole supporter of the French position), however, had not suffered spoliation: in addition, the Russian position was not totally disinterested, as Russia had purchased or received as gifts works that the French had requisitioned in Italy. The most famous of these pieces is probably the Gonzaga Cameo that was shipped to Paris after the French occupation of Rome, and then given by Josephine Bonaparte to Tsar Alexander I.

The picture changed rapidly after Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo: if before the former French emperor’s return the European powers had been more conciliatory with France, after the Hundred Days and Waterloo the attitude changed dramatically. The Treaty of Paris had divided France into several occupation zones managed by the Allied powers (the occupation lasted from June 1815 to November 1818), and after Napoleon’s return and final defeat a sense of revenge began to prevail among the European powers: even, scholar Henry de Chennevières, in 1889, went so far as to say that “without the epic of the Hundred Days, experienced as a bloody betrayal [...], the Louvre would have preserved its immense conquests.” Louis XVIII therefore decided to accept the restitution demands partly because France would continue to be under constant military threat from the occupying armies for some time: suffice it to recall that in Paris (which on the basis of the treaty division was occupied by thearmy of Prussia, which entered the French capital on July 8), a company of Prussian grenadiers occupied the Louvre on the orders of Chief of Staff Friedrich von Ribbentropp, because the museum’s director, Dominique Vivant Denon, who had served as commissioner of Napoleon’s army during the spoliations, had refused to tell the occupants where the works Napoleon had requisitioned from Prussia were kept. Vivant Denon, moreover, was also briefly held under arrest by the Prussians.

If, therefore, restitution was not discussed in depth during the Congress of Vienna, as this was not the priority for the European powers, after the end of the work the issue became increasingly urgent, so much so that it was discussed at length during the ministerial conference held in Paris in the summer of 1815, from July 12 to September 21. What prevailed was the changed British position: for if, as mentioned, before Waterloo the United Kingdom had not been in favor of restitutions, after the final battle the British placed emphasis on the links between an asset and its country of origin by virtue of its cultural connection. This position, in fact an important novelty in cultural policy since never before had the existence of a cultural link between a work and its country of origin been explicitly acknowledged in diplomacy, was enunciated in a letter that Lord Castlereagh, British Foreign Secretary, sent to Prime Minister Robert Banks Jenkinson. In the letter, Lord Castlereagh wrote that “only the principle of restitution can reconcile politics with justice.” This position would later be set down in black and white on the record by a lengthy note that Lord Castlereagh himself sent to the allies on September 11, 1815: “on what principle,” the British delegates wondered, “should we deprive France of her recent territorial acquisitions and preserve the plunder belonging to those territories which all modern conquerors have invariably respected as inseparable from the country to which they belonged?” By the end of the conference, among the victorious powers the principle of the restitution of works had prevailed over that of the integrity of the French collections formed as a result of the spoliations. On the French side, the restitutions were accepted, albeit with extreme reluctance and always under the threat of the use of force by the occupying powers, partly on the basis of a political calculation: in fact, Foreign Minister Talleyrand believed that acquiescing to requests for the repatriation of objects seized by Napoleon was a way to normalize diplomatic relations between France and the other European powers.

In any case, the restitution process did not go unchallenged. On the one hand, Vivant Denon and other cultural figures protested the destruction of a collection formed with the intention of making Paris the cultural capital of the world, while on the other hand those opposed to the restitutions opposed legal reasons, arguing theargument that the works had come to France as a result of agreements with the countries that Napoleon’s armies had occupied, or because of the legal status, also recognized internationally, of the occupied countries, for example Belgium, which had become an integral part of France, reasoning that it was argued that the French had been able to dispose of the works on Belgian soil as they saw fit (for the legal and cultural reasons for the spoliations, see also the dedicated article). The protests, however, were not enough to stop the flow of artworks, which, starting in July 1815, began to return to their countries of origin. The first returns were to the German states, to Austria, to Spain, to present-day Belgium and the Netherlands, and to the Italian territories that the Congress of Vienna had assigned to the Austrians (Venice and Milan) or to families linked to Austria (Tuscany, Parma and Piacenza, Modena). Restitution to the rest of the Italian territory also began in the fall.

The first restitutions that followed Napoleon’s second abdication were the Prussian ones, and they took place, as anticipated, by the use of force: in fact, Prussia did not wait for the end of the discussions among the European powers, and by mid-July 1815 the contingent that had occupied the Louvre had already been able to round up all the Prussian works in Paris and prepare them for return to Berlin. And so had statolder Wilhelm I, who, seeing requests for the return of Flemish and Dutch works fall on deaf ears, urged intervention by force from the Duke of Wellington, who held the post of commander of the Army of the Netherlands: thus it was that the Flemish and Dutch paintings requisitioned by the French could return to their lands, with the Belgian commissars working under the protection of the Duke of Wellington’s troops. By August commissioners from other countries had also arrived in the French capital to demand the return of their works. However, the scholar Paul Wescher wrote, “the greatest difficulty the foreign commissars encountered in asserting their rights arose from the fact that neither the foreign ministers, who met daily in Paris, nor the monarchs had taken any measures that covered all the countries concerned and their works of art.” This regulatory vacuum, which would never be filled, allowed Vivant Denon to frequently make opposition to requests for restitution, with arguments “often so drawn out as to border on the ridiculous,” Wescher wrote. A rather typical case of the arguments that the French opposed to restitutions is that of Giulio Romano’s Stoning of St. Stephen , which the French requisitioned from Genoa: the commissioner of the king of Sardinia demanded it back (and got it: today it can be admired in the church of Santo Stefano in Genoa), but Vivant Denon, who moreover had personally chosen it in 1811 during the height of the spoliations, refused, declaring it a tribute that Genoa had made to Napoleon. The picture, in short, was very varied, France often stonewalled, and there was not even a clause in the treaties requiring the French to return the works: the only reference was Lord Castlereagh’s note, which would later be appended to the documents relating to the Second Treaty of Paris, signed on November 20, 1815 to confirm the First Treaty of Paris, the Final Act of the Congress of Vienna, introduce new territorial changes, and establish the amount of reparations owed by France. So, without a clear legal framework, France was in fact forced to return the works that Napoleon had requisitioned, partly out of diplomatic calculation, partly so as not to suffer worse consequences (so much so that art historian Pierre-Yves Kairis has spoken of enlèvements to refer to the return to Belgium, i.e., “seizures,” adding that “pushing legal reasoning to the limit, one might consider that it is France that has the right to claim the paintings torn from the Louvre by the force of bayonets.”)

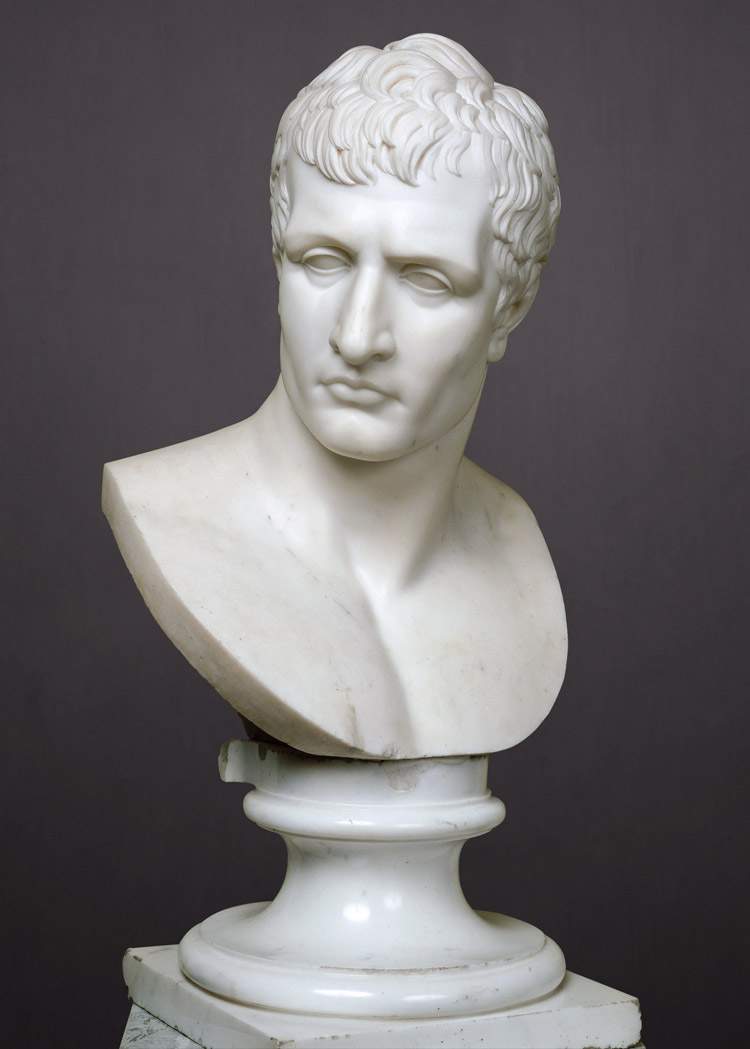

How did the Italian states act at this juncture? First, the states in the Austrian orbit, such as Lombardo-Veneto or the Duchy of Modena, moved: “From the end of August 1815, for about two months,” wrote scholar Valter Curzi, “Italian commissars, lists in hand, were busy tracking down the works and gathering them in the Austrian barracks of the Pépinière from where, encased and packed, they left for Milan between October 23 and 25 in a long and noble procession, consisting of forty-one wagons drawn by two hundred horses, which reached its destination in early December. Other consignments followed in the following months by land and sea; the whole operation could be said to have ended with the return to Naples in 1817 of the works stolen by Joachim Murat as he fled the Neapolitan capital two years earlier.” For the Italian states in the Austrian orbit (Lombardy-Veneto, Parma, Modena and Tuscany), the person in charge of restitution was the painter Joseph Rosa, director of the Viennese museums, aided by the commander-in-chief of the Austrian army, Prince Karl Philipp von Schwarzenberg. It was precisely Schwarzenberg’s troops who, despite the open hostility of the Parisians, pulled down from the Arc de Triomphe the horses of St. Mark that would later depart for Venice: to make the operations possible without provoking clashes, the Austrian soldiers had to work at night, and by blocking the access routes to the Arc de Triomphe. For the Kingdom of Sardinia , minister plenipotentiary Luigi Costa arrived in Paris. The Papal States sent as commissioner for restitution the great sculptor Antonio Canova, charged with bringing the treasures of the Vatican Museums back to Rome. This was not an easy task, because the Papal State had handed over its works to France on the basis of the agreements of theArmistice of Bologna in 1796 and the Treaty of Tolentino in 1797. Canova himself, upon arriving in Paris, lamented the existence of obstacles that he said were almost insurmountable: in addition to legal and practical difficulties (in fact, it was not easy to trace the works scattered all over France), some foreign diplomats in fact preferred that the works from the papal collections remain in Paris, not to mention the opposition of Vivant Denon. The mission succeeded because Canova could count on the support of Austrian Chancellor Klemens von Metternich, who pressured the French to go along with the papal demands, as well as on the support of the United Kingdom (which Canova obtained by exploiting his diplomatic channels, made possible by his clients), and on the protection of British and Austrian arms: even in his case the restitutions had to proceed practically manu militari. Eventually Canova managed to bring back almost all the Roman works, deliberately omitting to ask for 23 paintings that were kept in some provincial museums, as a gesture of showing his good will. Works that were difficult to transport also remained in France. On the other hand, some Roman paintings, such as those that belonged to the Braschi collection, which can still be seen in the Louvre today, remained in France because the family obtained financial compensation from the French in exchange for the paintings, which is why the papal delegation’s requests for restitution (insisting on this apparently had been the then deputy director of the Vatican Museums, Alessandro d’Este) in this case were not followed up.

Several works were returned to Italy, although the restitution, scholar David Gilks has written, was “achieved by bayonet rather than through the rule of law, giving the impression that the alliance was abusing the rights of the fittest.” And so it is thanks to this action, which combined diplomacy and the use of force, that today many masterpieces can be admired in Italian museums, or in the churches from which they were taken. Among the works returned, many are symbols of Italian art history. In Rome, Raphael’s Transfiguration and Portrait of Leo X with Cardinals Giulio de’ Medici and Luigi de’ Rossi , Perugino’s Resurrection , the Capitoline Venus, and the Apollo del Belvedere returned. Venice regained Titian’sAssumption of the Virgin and the Horses of St. Mark, among other works. Andrea Mantegna’s San Zeno Altarpiece made its return to Verona, which can now be admired in its church (although two panels of the predella remained in France, and recently it was precisely from France that a proposal was made to return them to Italy). In Bologna it is again possible to admire Raphael’sEcstasy of Saint Cecilia and Guido Reni’s Massacre of the Innocents . Florence got back Parmigianino ’sMadonna with the Long Neck and the Venus de’ Medici. Parma got back Giulio Cesare Procaccini’s Marriage of the Virgin and Bartolomeo Schedoni’s Marys at the Tomb.

Theextent of the restitutions depended, Curzi explained, “on the diplomatic ability of the individual commissioners in charge of restitutions and the commitment of the governments.” So, in conclusion, how many works returned to Italy after the restitutions of 1815? It is possible to make a calculation by relying on the catalog compiled by Marie-Louise Blumer in 1936 in the Bulletin de la Société de l’Histoire de l’Art, which is based on the catalog that was compiled by Antonio Canova when he was sent to France. Since this is therefore a two-hundred-year-old document, it may have been inaccurate or complete, but it still gives a rather plausible idea of the extent of the requisitions: according to this catalog, the French requisitioned a total of 506 works in France, 249 of which were returned in 1815, 9 went missing, and 248 remained in France: of these, about fifty are on display today in the Louvre, and the others are divided between the Louvre’s storerooms and several other French museums.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.