History of the Florentine commesso, an ancient technique of high craftsmanship

It is not clear to what period the invention of inlays in semi-precious stones dates: what is certain is that since the 16th century the city of Florence has linked its name to this art, so much so that even today it is better known as commesso fiorentino or, more improperly, “Florentine mosaic.”

It is immediately necessary to distinguish between two different forms of inlaying hard or siliceous stones: the first commonly best known is employed in antiquity and is the child of goldsmithing techniques or those derived from cabinetmaking, and involves the insertion of tesserae or segments of hard stone into special cavities cut in a supporting material, which can range from ivory to metal. While another kind of marquetry is that involving the juxtaposition of hard stones with each other or with other material, arranged over a common base. In the former case the stones are used only with a decorative function, while on the contrary in juxtaposition the stones are used as solid elements, whose colors could be substituted for liquid colors. Art historian Gabriella Gallo Colonni in the irreplaceable handbook Le tecniche artistiche, conceived by Corrado Maltese, debates whether the renewal of the latter technique was to be traced to Florence or rather to Pavia. In the Lombard capital, in fact, engaged in the monumental construction site of the Certosa Di Pavia, the technique in commesso in pietre dure was being employed.

To support this second hypothesis, it should be recalled how Giorgio Vasari testified to “the very great difficulty of working stones that are very hard and strong” that Leon Battista Alberti had encountered when he found himself carving some letters in porphyry for the main portal of the church of Santa Maria Novella, proof that in Florence this type of workmanship was still unripe. Moreover, it was from Pavia that masters who knew the secrets of this form of craftsmanship arrived who were called to Florence by Grand Duke Francesco I in an attempt to set up a manufacturing workshop in the casino of San Marco.

But it was in particular Francesco’s brother Ferdinando, who upon becoming Grand Duke wanted in 1588 to transfer such workshops to the Uffizi, bringing them together under the name of “Galleria dei Lavori” (later to become the Opificio delle Pietre Dure) and endowing them with a precise order, and then employing them in the prestigious commission for the covering of the family mausoleum at the Basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence.

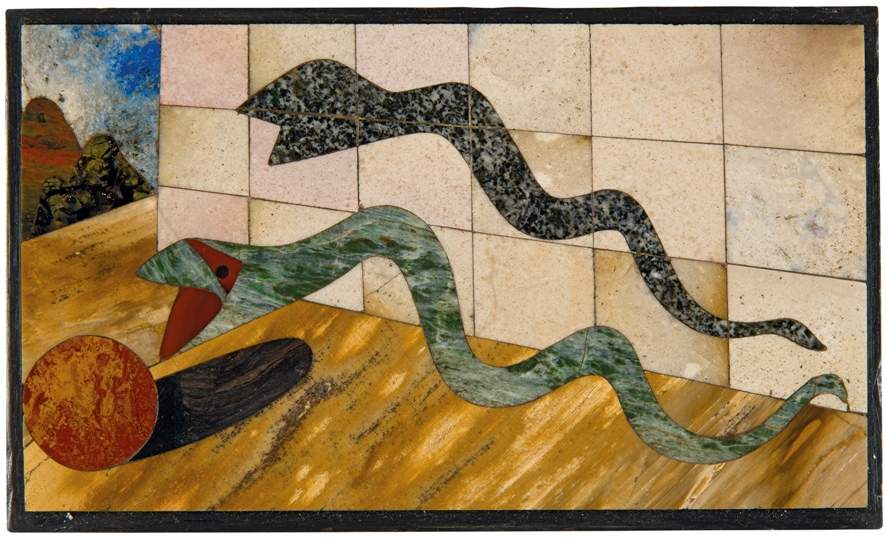

Over the centuries, the technique of commesso reached extremely high levels of virtuosity, in a continuous trial to attest itself as “painting in stone,” moving from geometric or abstract compositions to complex pictorial themes, thanks to a cutting of the stones that became increasingly minute and precise. In the Baroque era, this art radiated from Florence to many European courts, where Florentine craftsmen were not infrequently called upon. Such workmanship therefore spread throughout Italy, France, Spain, Germany and even India. In the East, it would attain its own characters of originality, placing precious stones alongside semi-precious stones, and giving rise to personal floral decorative motifs, which are also found in the sumptuous mausoleum of the Taj Mahal.

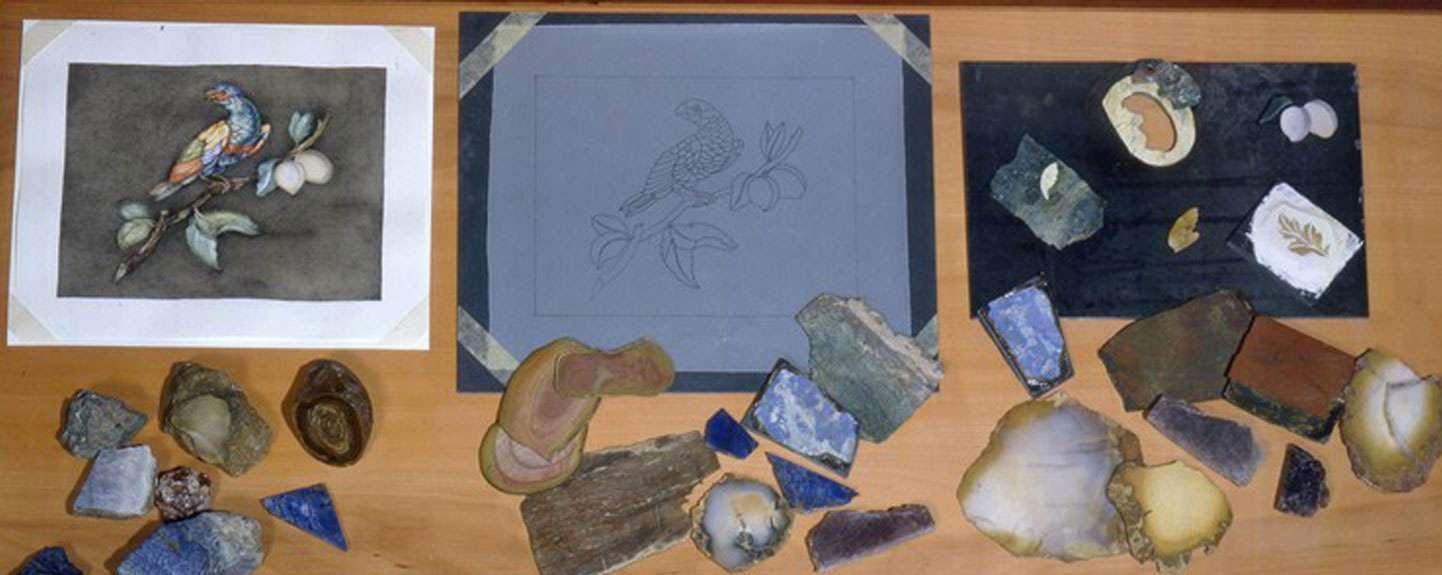

The workmanship of the Florentine commesso involves the creation of a design on cardboard provided by an artist, for which a careful choice of stones is then opted for, with the intention of rendering as faithfully as possible the various hues, shades and chiaroscuro. The many materials are used, including colored granites, porphyry, lapis lazuli, Sicilian jasper, as well as the most diverse marbles.

To this day, the technique used in the Florentine Opificio’s restoration workshops has remained essentially unchanged, with the only difference being in the preparation of the stone slabs, which is no longer done by hand but conducted by electronically operated frame saws. While smaller pieces are still cut with a wire saw that, following the contour, drags the abrasive mixture (emery and water) cutting the stone. Note that unlike mosaic, the sections are not reduced to geometric tesserae, but follow the lines of the design. Next, finishing work is done, with the file, to make sure that even the smaller pieces connect in the clerk without leaving the joining lines visible. Finally, the interlocking placed and polished parts are fixed with adhesive mixtures such as wax. This process also allows the creation of works no more than 2-3 millimeters thick, then placed on slate slabs that serve as the base.

The commesso can be used in architectural decorations, such as in the aforementioned Chapel of the Princes in the Basilica of San Lorenzo, but also for making furniture, such as cabinets, paintings or tables. An example of the latter use is the splendid table depicting a view of the port of Livorno, kept in the Uffizi. It is a semiprecious stone commesso, with a background of lapis lazuli from Persia, figures in jaspers from Sicily and Bohemia, agate from Siena and chalcedony from Volterra, made between 1601 and 1604 by the Lombard carver Cristofano Gaffurri, based on a design by Jacopo Ligozzi.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.