History of Italian art from 2000 to the present. Part 4: contemporary Italian painting

We know full well that the theory of the eternal return of the same developed by Nietzsche does not represent a regular philosophical exposition, much less a potential scientific hypothesis, so much as a dark prophecy. But as in dystopian novels, which show us an alternate and terrible reality to make us reflect on our society, the notion that the universe is cyclically reborn and removed also indicates something about our understanding of existence. For example, it makes us dwell on the fact that if something happens only once and then dissolves into the void, it is almost as if it never happened. If we imagine it isolated in the ocean of happenings of which existence is composed, in fact, it turns out to be rather marginal. In contrast, they take on a more defined volume of being those things that are hard to die for, that despite periods in the shadows sooner or later come up again. In the art world, this role is undoubtedly filled by painting.

It was perhaps the first creative expression to be born (with cave art), it will surely be the last to die. If from the postwar period until the 1910s in Italy (as in the rest of the West) the putting of forms and colors on canvas, except for the interlude of the Transavantgarde, had given way to new and unconventional solutions, in the last two decades we have witnessed the re-emergence of the medium dearest to most enthusiasts. To do so, however, painting had to accept, at least at an early stage, a compromise with the experimentation that had marginalized it for decades. In essence, in order to return to the contemporary scene, paintings had to agree not to take the outward form of painting on canvas, at least initially transcending the concept of two-dimensionality and subverting the usual spatial relations with the viewer.

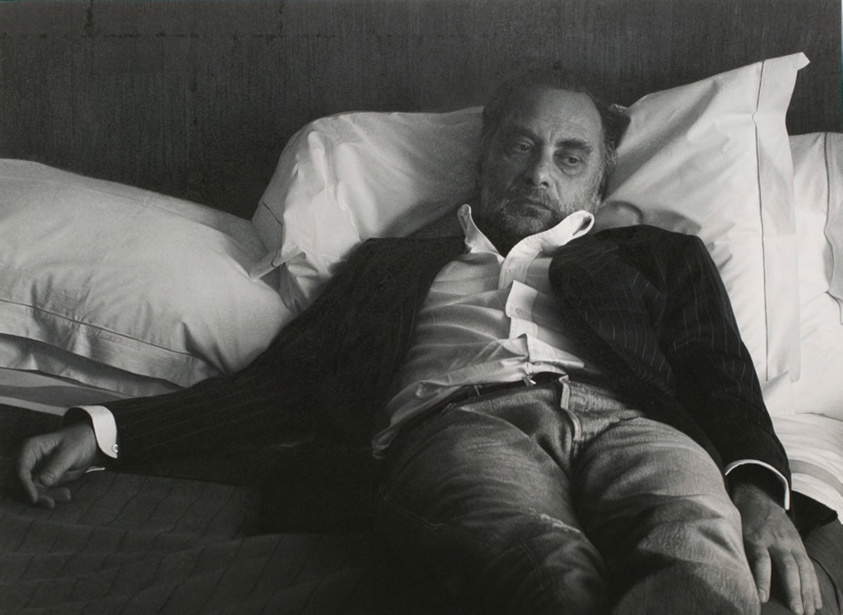

In Italy, the main interpreter of this hybrid current was undoubtedly Rudolf Stingel (Merano, 1956). Born in South Tyrol, the painter began to make a name for himself in 1989, when he produced an Instruction Manual that illustrated how to make his abstract paintings. In 1991 he inaugurated the use of the carpet, which at the Daniel Newberg Gallery in New York stands out in its bright orange within the white gallery. An experiment he repeated in much the same way at the Venice Biennale two years later. In the 2000s he continued to experiment, using unusual media such as Styrofoam and Cellotex for his pictorial installations, and seeking audience participation (see relational art). As the years progressed, the painter increasingly “cleaned up” his pictorial exercise, bringing it more frequently to the usual tracks of canvas and figurativism(Untitled (After Sam)), but without abandoning either abstraction or the various experiments that have made him famous. In 2013, for example, he covered the entirety of Palazzo Grassi in Venice with an oriental patterned carpet.

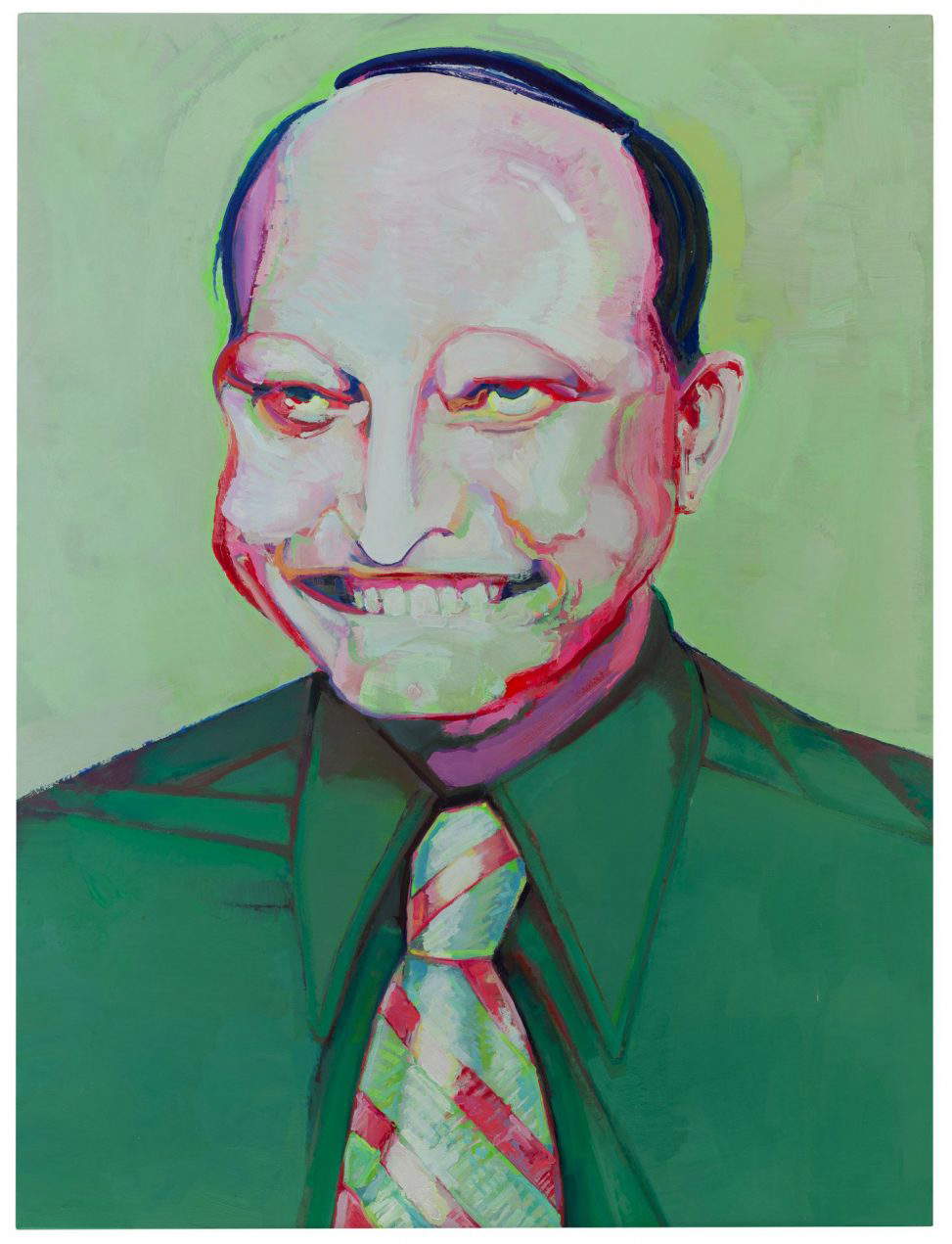

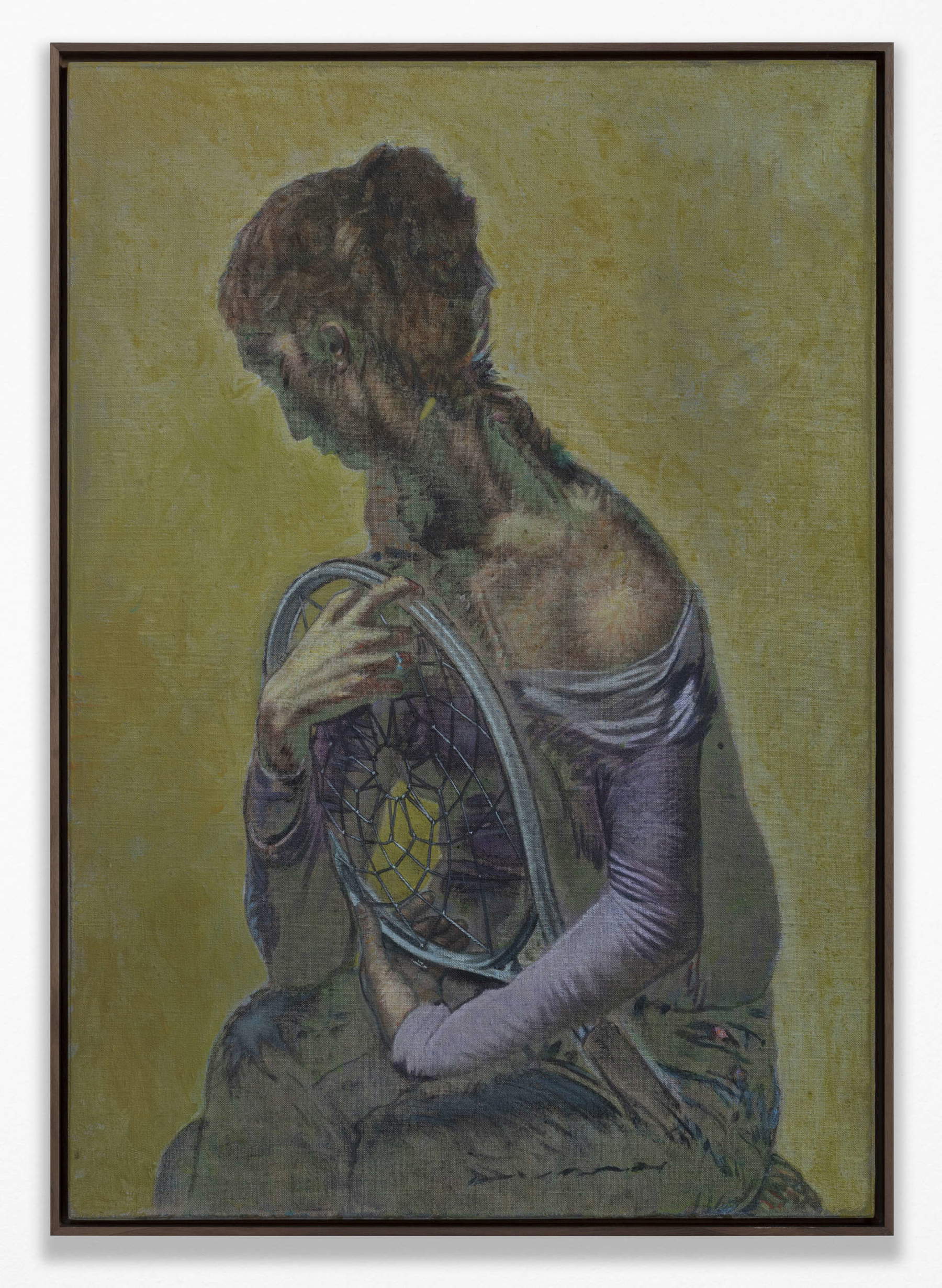

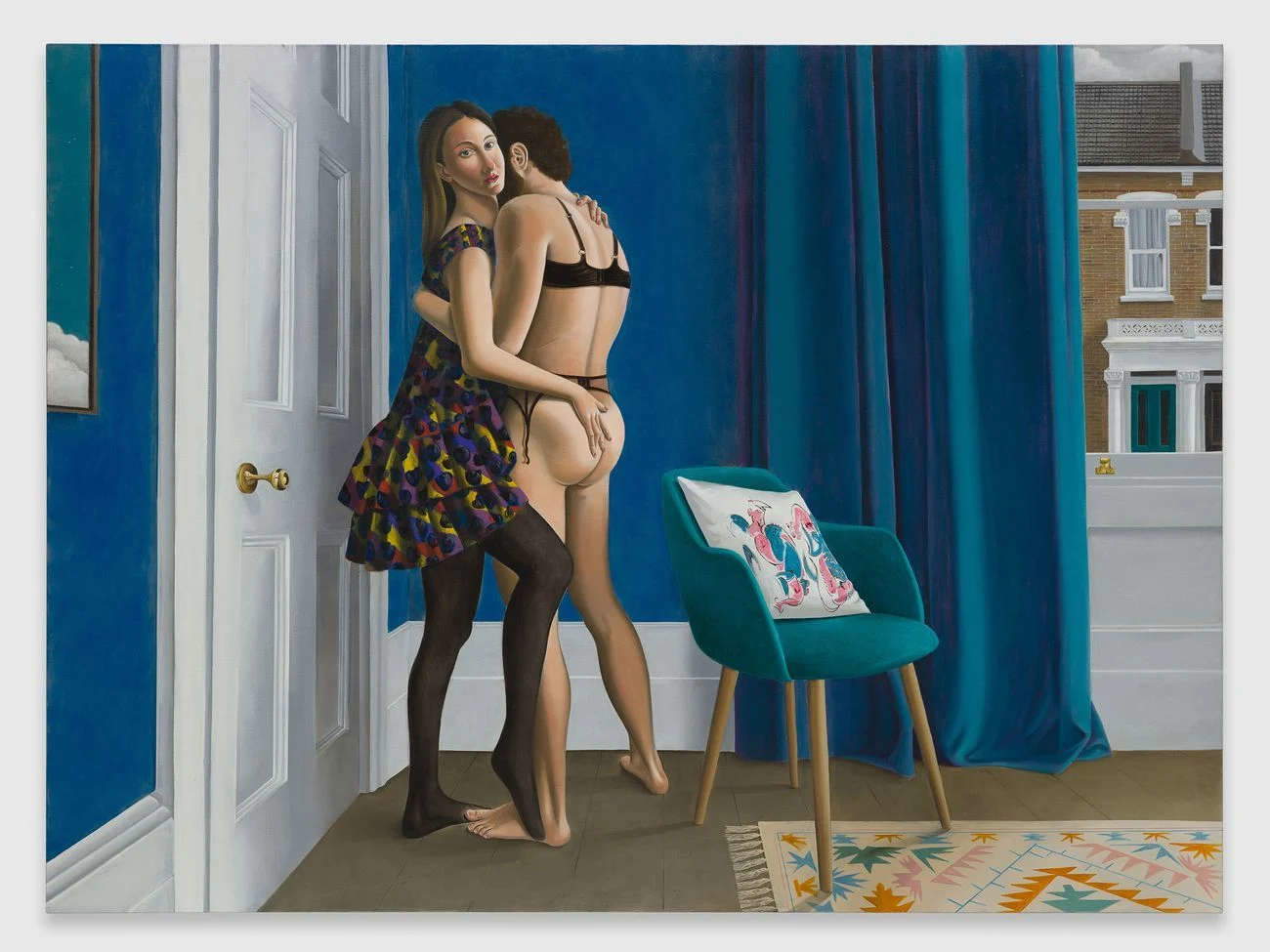

In perhaps an even wider interregnum has moved Roberto Cuoghi (Modena, 1973), who over the course of his career, official website in hand, has experimented with at least 19 different mediums, from sculpture to performance, photography to music. These include painting, which he has interpreted in heterogeneous keys: expressionist, pop, abstract, hyperrealist. Always with full technical mastery and fine aesthetic audacity. Examples are the Black Paintings, such as Untitled (Black globe with vignettes) from 2003, where he evokes an abstract landscape thanks to various materials, from graphite to satin-finished Plexiglas. Or D+P(XIXA)mm (2010), a diptych of pastel, chalk and compressed air on paper and setacryl that depicts a man portrayed on what looks like two plates. Increasingly, especially in recent years, his painting has been concerned with portraiture, for example in P(XVPs)po, 2020, often giving a hallucinatory and lysergic interpretation, or with an abstractionism of a real-life matrix as in P(XLVIIIPs)po, 2022, or inherent to textures.

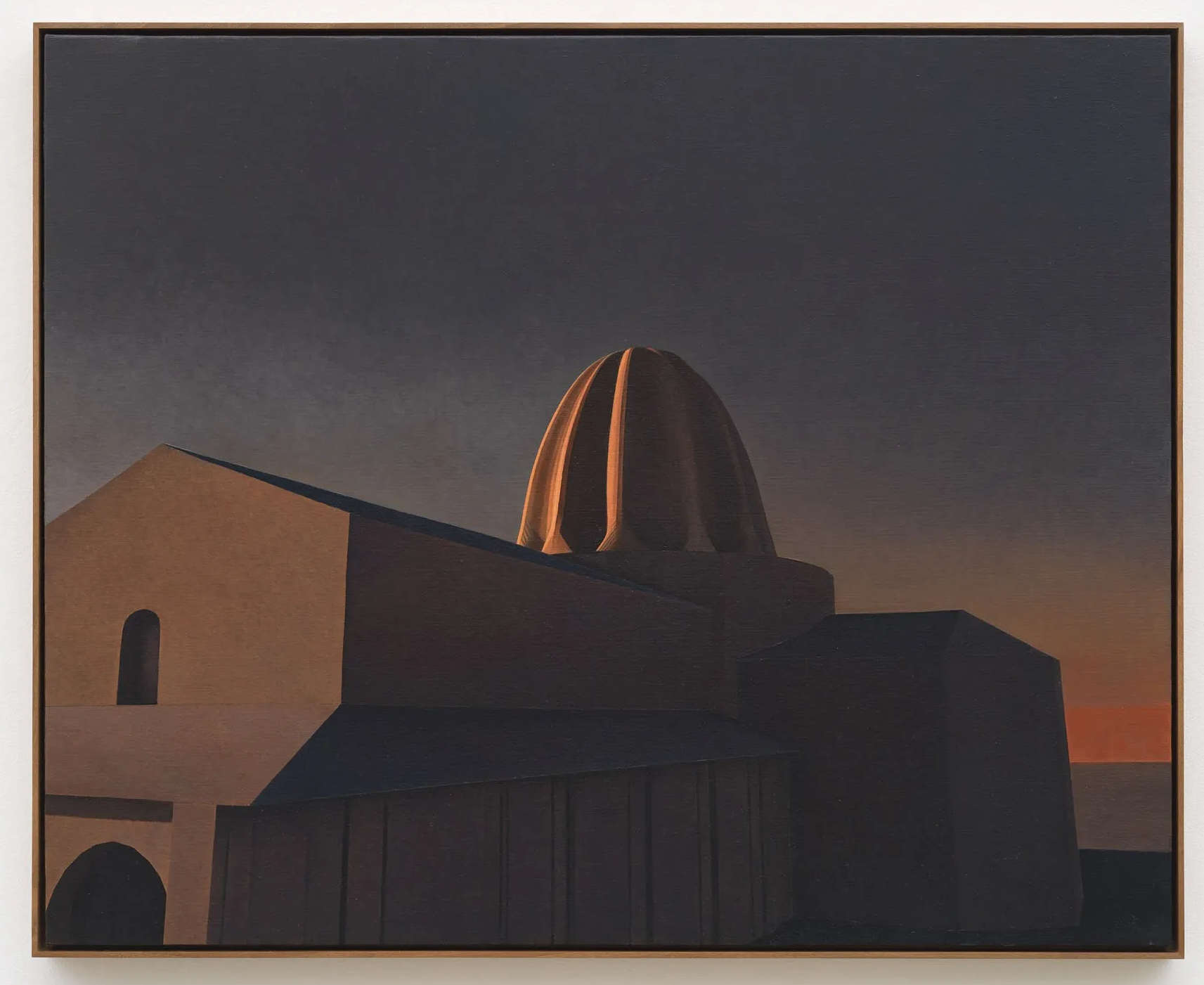

A similar path, though less histrionic and conceptually much more tied to painting, is that of Pietro Roccasalva (Modica, 1970), who over the years has nonetheless made several forays into performance, photography, sculpture and video. Like his aforementioned colleagues, Roccasalva enjoys such eclecticism and technique that allows him to move between styles and poetics, contaminating so many suggestions that he finally finds his own unique voice. For him, citationism is not rhetoric, but an opportunity to generate convergences between very distant stylistic forms-Assyrian, Cubist, neoclassical, Renaissance-to generate momentary or lasting points of contact, aesthetic short-circuits with a mysterious spark. Why does a rooster wear a Swiss guard outfit(Untitled, 2010)? Why does The Western Bride (2021) seem to be mirrored in a tennis racket whose strings are intertwined in a kind of mandala? Why is it that in the metaphysical Untitled (Jocundity VII), 2020, the dome of the strange building is so reminiscent of a juicer? Few answers and much poetic suggestion emerge from a labyrinthine, flowing painting of a thousand derivations and outcomes.

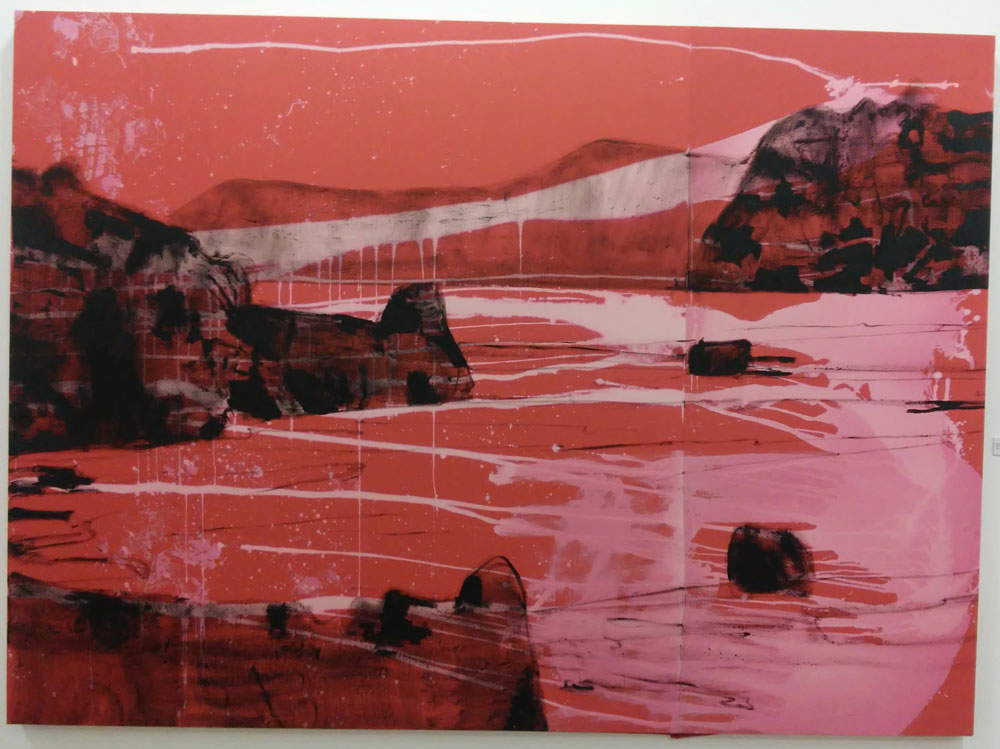

More pronounced is the pictorial fundamentalism of Giovanni Frangi (Milan, 1959), who has also tried his hand at sculpture several times. Emblematic of the dialogue between the two was the booth that the Galleria dello Scudo of Verona brought to Miart, the contemporary art fair in Milan, in 2001, which featured paintings of widely varying sizes juxtaposed with sculptures that rose from the floor onto the walls. However, Frangi finds his full stylistic signature in the paintings with a naturalistic theme, where, however, nature manifests itself altered in color and form, moving on an ambiguous ridge open to suggestions, which could recall both Gauguin’s coloristic interpretation(Dauntsey Park) and the American color field(Usodimare, 2016). Wanting to narrow the field further and bring us closer to the present day, even more representative are the works in which the natural element seems suspended, dangling over the abyss of abstractionism(The Law of the Jungle, 2015) or fully abandoned to it(September, 2016).

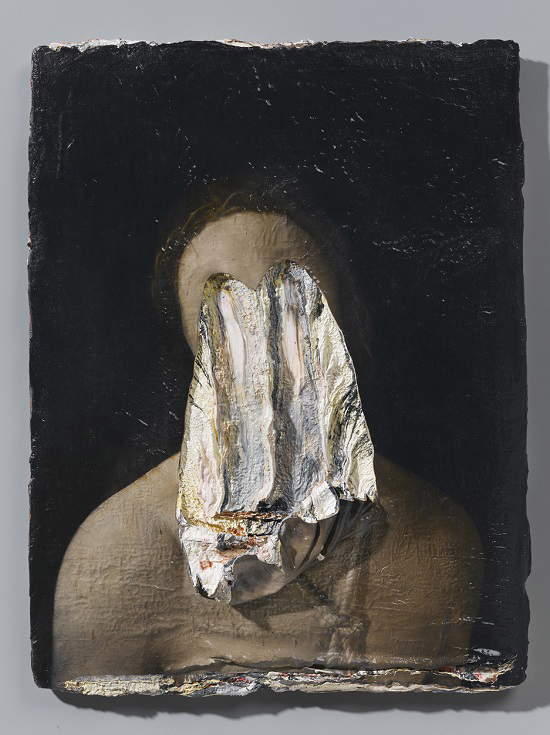

Nicola Samorì (Forlì, 1977), who then like Frangi specialized in the use of the paintbrush, also started from a balance between painting and sculpture. Starting by copying works, especially from the 16th and 17th centuries, the artist intervenes by transforming and reinterpreting them to the point of distorting their essence. It is particularly portraiture that suffers the consequences, with faces often covered(About Africans, 2013; JV, 2009) or scarred(Penthesilea, 2018). Intentions he directly explicates: “I flog painting to see it bleed, because I consider it in the same way as a body that is treated as a now anemic organism, when it is not at all. The images and their narration are functional to this staging that needs the metaphor of flesh to make itself unequivocal.”

Also evoking historical reminiscences are the works of Patrizio Di Massimo (Jesi, 1983), which orbit the Baroque in dramatic tone. They, content-wise, however, adhere sharply to contemporaneity, staging moments of everyday life, which the painter elevates to poetic instants with a saturated, hyperrealist style. Moreover, he often makes himself the protagonist of domestic and ordinary scenes, stepping into very different contexts from time to time, oscillating from artistic reference(Self-Portrait with Philip Guston, 2022; Bauhau, 2019) to a perturbing dimension that anchors itself to realism while winking at a sober current of surrealism(A Blue Room, 2021).

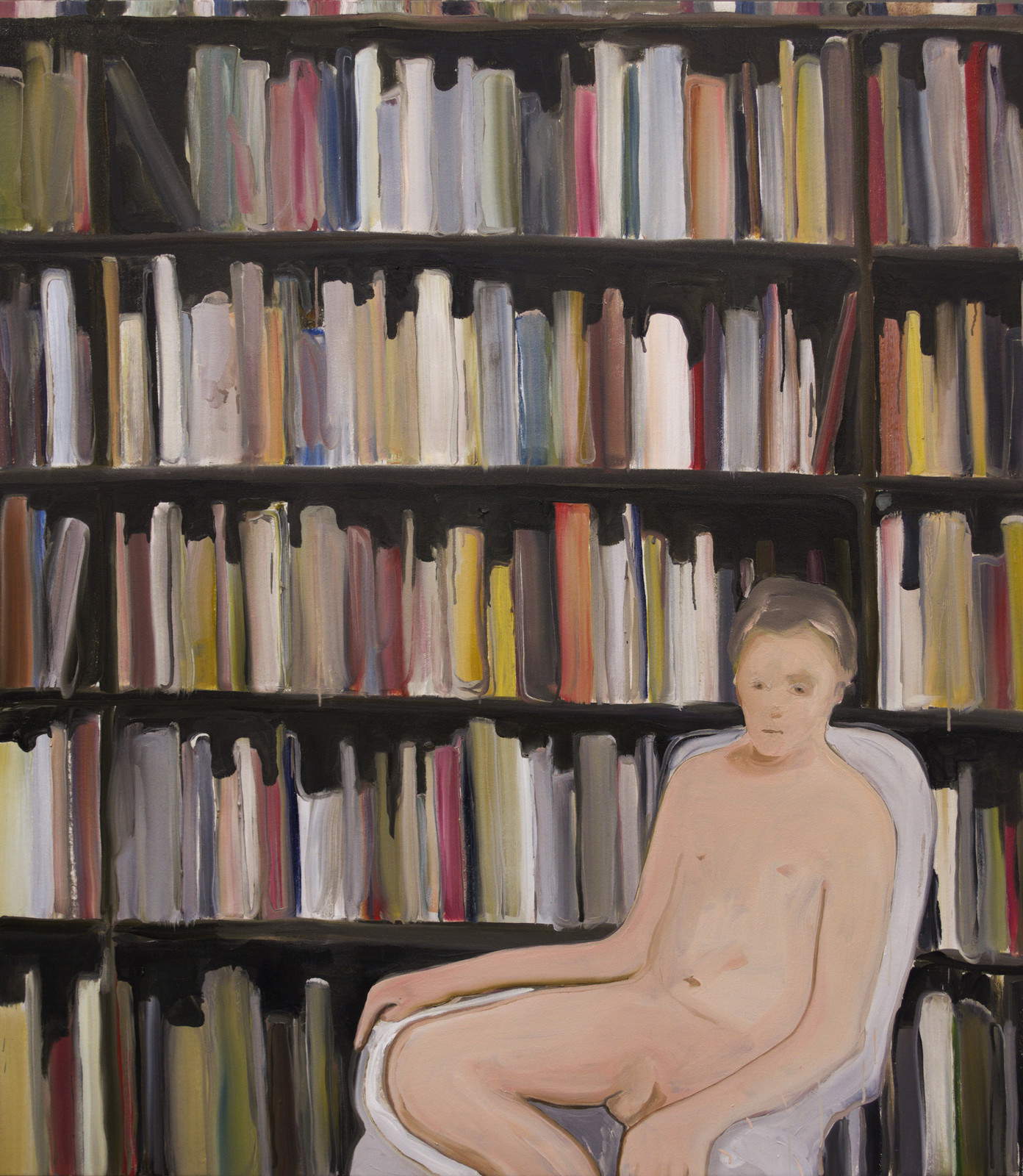

Like Di Massimo, there are other painters who in recent years have managed to distinguish themselves in the group of authors who carry a new pictorial language, mostly characterized by an effective blend of contemporary content and 20th-century echo formalisms. Among them is Rudy Cremonini (Bologna, 1981), who specializes in the use of oil paints, which he applies on canvas without first delimiting the field of intervention with a preparatory drawing. The painting thus results free, liquid, immersed in a dreamy atmosphere, reminiscent precisely of the happenings we experience in sleep, without precise boundaries of existence. It evokes images that resonate from our imagination, memories, fears and insecurities. Often interested in circumscribed or enclosed living spaces, Cremonini portrays human subjects in domestic settings The lord of the archive, 2019), animals in zoos(I am a flamingo in your eyes, 2015), exotic plants in greenhouses(Pink cactus, 2018) or close ups of landscapes so narrow that they too are confined(Intricate, 2021). Plants and dreams are also understood by Thomas Berra (Desio, 1986), an author who hits another fundamental point of contemporary painting, not only Italian: the cancellation of the distinction between figuration and abstraction. In this third dimension, born from the dialectical clash of the previous ones, Berra works both when he chooses a human subject (often rendered in a two-dimensional, essential and minimal way, as in Non c’è niente che sia per sempre, 2021) and when he addresses himself to the plant world. In particular, the latter sphere is the subject of the research that has been engaging him since 2015. On the other hand, it is the perfect space of investigation for his style, the one that gives him the opportunity to lace himself with reality, as well as to determine abstract patterns or indulge in the flow of undisciplined signs and swirling colors(In Praise of the Wanderers).

Bodies, spaces and objects also encroach on each other in the painting of Guglielmo Castelli (Turin, 1987). Animated by an intimate and personal approach, the author sets up situations of great dramatic depth, where vivid American-style colors combine with European-style Symbolist hints. Always cloaked in a veil of melancholy, his paintings are figurative while starting from concepts inherent to abstraction, such as the distribution and balancing of chromatic levels, matter, its excesses and removals. To do so, Castelli operates at a certain distance from the canvas, approaches it performatively by interacting with it from different perspectives. Once again, then, it becomes evident how on deep analysis every artistic expression, ancient or current, is to be inscribed within a flux in which singularities are difficult to isolate. Every experience fits into a context susceptible to infinite expansion, to making connections and reviving references to the bitter end. This makes the undertaking of the historian and critic -- called upon to select frames from this flow, to lock in elements and elevate them to symbolize a more complex core of events -- particularly arduous. We have tried, aware that analyzing times so close, perhaps too close to be well focused, is even more so.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.