One of the most innovative and original art historians of the twentieth century was, without a shadow of a doubt, Roberto Longhi (Alba, 1890 - Florence, 1970): precocious talent (before he was thirty years old he had already written fundamental essays), heir to the purovisibilist tradition which he updated and modernized, completely devoid of reverential fears towards the great “masters” of art criticism, to the point of bordering, and sometimes even touching, insolence, especially towards Bernard Berenson, with whom he provoked a controversy that lasted decades and was never fully clarified (suffice it to say that, some forty years after the first rifts, the two met and Berenson mockingly asked Longhi how it felt to be married to a genius like Anna Banti). However, despite the fact that Longhi and Berenson were divided by personal frictions and also by beliefs in art history (Longhi had plans to revise and improve Berenson’s method), it is possible to discern a common basis in the approach of both. This basis is formalist criticism, the starting point of Berenson’s reflection as well as Longhi’s.

Longhi had approached art criticism by reading the works of Konrad Fiedler, Adolf von Hildebrand, and especially Heinrich Wölfflin, and the results of these readings are particularly evident in the early essays, dating from the 1910s, written when the scholar was not yet twenty-five years old. Particularly interesting is I pittori futuristi (The Futurist Painters), an article published in 1913 in the magazine La Voce: here Longhi, who clearly has Wölfflin’s categories well in mind, makes a juxtaposition between Futurism and Cubism, moving, in a sense, in the furrow of the characterizing polarities identified by the Swiss scholar. Let us read, by way of example, a passage about a work by Boccioni: "in the Scomposizione di figure a tavola (Decomposition of Figures at the Table ) it is light that is given the integral power to set matter in motion, since an edge of the glass struck by a ray soars into a tremendous and indefinite envolée. From the study of the superficial planes of Cubism, in order not to freeze matter rather to unleash it, he came to conceive it as a superposition of planes that flake off, that small themselves as if around a compact central nucleus: and it is the rotary motion imparted to this nucleus that makes it unwrap its form outwardly as Saturn frees its rings from itself." Longhi, in other words, notes how one of the characteristics that can give movement to the work of the Futurists is the superimposition of planes, an element absent in Cubist painting: it is, in a way, the juxtaposition of surface and depth that Wölfflin had already mentioned.

|

| Umberto Boccioni, Scomposizione di figure a tavola (1912; oil on canvas, 70 x 80 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Roberto Longhi |

However, the Piedmontese art historian did not move solely within the canons of formalism and pure visibility. In fact, Longhi had also looked to the great tradition of the connoisseurs, from Giovanni Morelli (towards whom he nevertheless maintained a very critical attitude) to Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle. Perhaps it stems precisely from Longhi’s high regard for Cavalcaselle that he had the attitude of considering theeye the supreme means of art history: for Longhi, there is no history of art that can disregard the study of works from life. He too, like Cavalcaselle, had often undertaken long journeys to study works of art from life. One of the first was the one that took him to Sicily to discover the works of Caravaggio, which Longhi intended to study for the thesis he discussed at theUniversity of Turin in 1911 with his first great teacher, Pietro Toesca: consider that Caravaggio and Piero della Francesca were the two artists who most attracted Longhi’s attention, and these were artists who were substantially little known at the time. It is worth mentioning a couple of paintings whose attributions to Piero della Francesca and Caravaggio, first formulated by Roberto Longhi, are now taken for granted: the Madonna and Child by Piero formerly in the Contini Bonacossi collection in Florence (and now in the United States) and Caravaggio’s St. Jerome the Penitent preserved at the monastery of Santa Maria de Montserrat in Catalonia. It is worth making a few brief remarks about the latter work, to which Longhi returned on several occasions throughout his scholarly career, because it is interesting for trying to understand his method more fully.

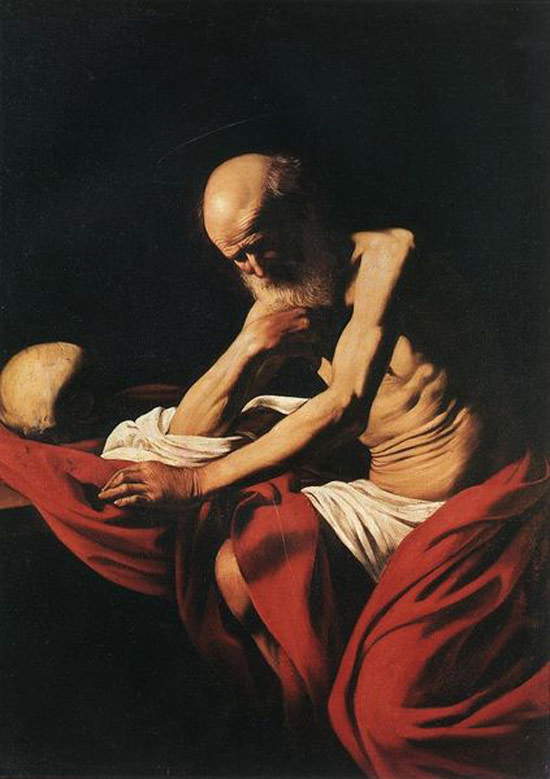

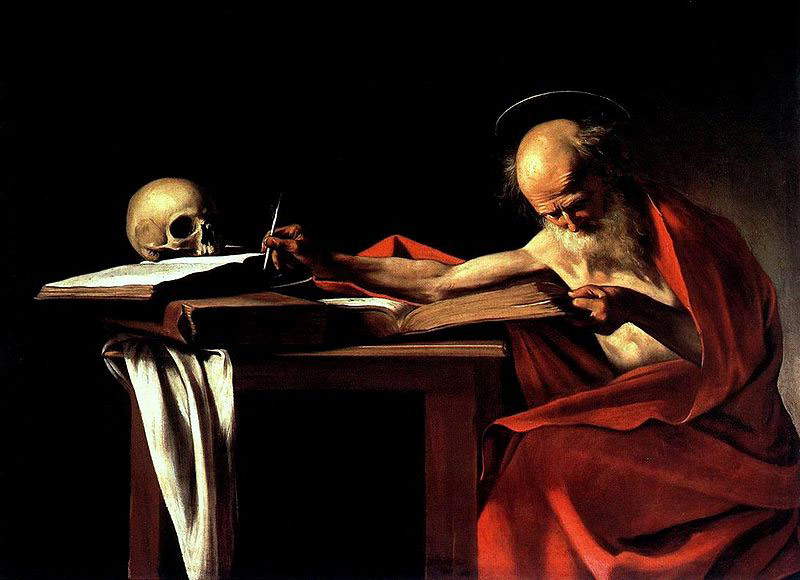

Longhi saw it for the first time in 1913, when it was kept in Rome at the Magni collection (thus shortly before it was acquired, in 1917, from the monastery of Montserrat): that was the occasion on which the art historian first advanced the name of Caravaggio. Longhi had found that the model the Lombard artist had used for the painting was the same one he had posed for the San Girolamo in the Galleria Borghese, whose Caravaggesque authorship was undisputed. But beyond that, Longhi noted, there are similarities of a different kind between the two paintings. For example, the motif of the skull resting on the table that recalls St. Jerome’s head and is offered to the viewer from the same point of view and in more or less the same light conditions: details that emphasize and highlight the saint’s condition and the depth of his meditation. One can see how Longhi first studied the formal specificities of the work (the details and connotations that would allow him to identify in the model of the Saint Jer ome of Montserrat the same one who posed for the Borghese Saint Jerome ) and later the narrative attitudes, the way in which the artist makes evident his own poetics (in this small example, the motif of the skull that recalls the saint’s head). It is mainly around these two poles that Roberto Longhi’s attributive technique revolves: form and narrative attitudes. Longhi’s work would not make sense, however, if one did not consider a concept that was fundamental to him, that of relationships.

|

| Caravaggio, Penitent Saint Jerome (c. 1605; oil on canvas, 118 x 81 cm; Monistrol de Montserrat, Monastery of Santa Maria de Montserrat) |

|

| Caravaggio, Penitent Saint Jerome (1605-1606; oil on canvas, 112 x 157 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

Wrote Longhi: “The work never stands alone, it is always a relationship. To begin with: at least a relationship with another work of art. Unopera alone in the world would not even be understood as human production, but looked upon with reverence or horror, as magic, as taboo, as the work of God or of the sorcerer; not of man. It is thus the sense of the opening of relationship that gives necessity to the critical response. A response that involves not only the nexus between work and works, but between work and world, sociality, economy, religion, politics and whatever else is needed.” The work of the art historian cannot disregard the relationships that a work establishes first with other works of art, and then with its surroundings. It is true that Longhi, as an art historian trained in the groove of formalist criticism, accorded precedence to the formal values of the work of art (but formal values must also be read, after all, in relation to other formal values of other works), but this does not mean that the scholar underestimated the context within which the work is set. We are already, however, in a mature phase of Longhi criticism (the above lines date from 1950), and it should be noted how it changes over time: Gianfranco Contini, a scholar as well as a friend of Roberto Longhi, identified several periodizations to summarize Roberto Longhi’s career, summarized in a commemorative speech delivered at the Accademia dei Lincei. Cultural context, however, remains something that, for Longhi, comes later. Mina Gregori also recalled this in a recent interview: to be “Longhian” means “to privilege the eye,” “to put museums before libraries,” “to put direct vision of the works before photographs,” because “the Longhian method was absolutely antithetical to the school of Giulio Carlo Argan who, otherwise, professed a contextual approach. If you are a Longhian you start with the work and it will also tell you its context.” Analysis of context that is nonetheless present: for Mina Gregori, Longhi’s vision was not “mere formalism.” The object from which to start is, however, the work: “the construction of the context and the related criticism must be reached only later, since lacquisition can only take place primarily through locchio, and then dallopera; then follow philology, historiography, criticism [...].” Consulting sources and libraries remains an operation of fundamental importance, but still subsequent to the study of the work.

Today, Longhi is considered one of the greatest art historians ever, and there are even those who consider him the greatest Italian art historian of the 20th century. His original method, his prose with a narrative character (his aim was to find an adequate verbal equivalent for the forms of the works), his direct character bordering on boldness, and his remarkable civic commitment to the art-historical heritage (a natural consequence of his way of understanding works of art, mentioned above) have made him a figure of reference for generations of scholars. Among his direct pupils are legions of art historians who have written memorable pages: in addition to the aforementioned Mina Gregori, it is possible to mention the names of Francesco Arcangeli, Carlo Volpe, Enrico Castelnuovo, Giovanni Testori, Andrea Emiliani, Giovanni Previtali, and Luciano Bellosi. But Longhi’s lesson was transversal, because it was also important for personalities who worked in other fields: they also studied with Longhi, for example, Arbasino and Pasolini. Names that make us understand how high was Roberto Longhi’s contribution to art history and to all culture.

Reference bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.