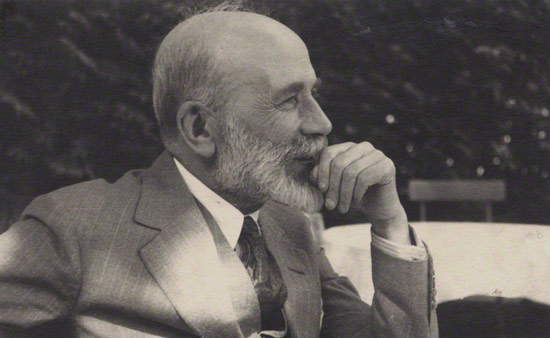

We resume our brief history of art criticism to talk about one of the most important scholars of the past: Bernard Berenson, born Bernhard Valvrojenski (Butremanz, 1865 Florence, 1959). Originally from Lithuania and emigrating to the United States with his family in 1874 because of religious persecution against Jews, Berenson first studied in Boston and then enrolled at Harvard University, where he studied literature. It was during his studies that Berenson became interested in art: in fact, he began attending the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, studying Italian artists in particular, which he was later able to study in depth with a trip to Europe that he made in 1887, after earning his degree. It was during his stay in Europe that he decided to devote himself completely to art history.

|

| Bernard Berenson |

Decisive was his knowledge of Giovanni Morelli’s studies, which exerted an important influence on the young Berenson. He thus procured a copy of Kunstkritische Studien über Italienische Malerei (Studies of critical darte on Italian painting, Morelli’s main work) and pondered reviewing it. The young Lithuanian-American thus wrote a twenty-page essay, which was never published but was later found among his papers. It was in this work that Berenson first expressed his admiration for Morelli: in his opinion, Morelli’s “services rendered to the science of images” “are more important than those rendered by Winckelmann to ancient sculpture or those rendered by Darwin to biology.” Berenson also got to know Morelli in person, through another art historian, the Frenchman Jean-Paul Richter (and in the same period, that is, between 1889 and 1890, Berenson also got to know Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle): at least on the human level, however, Berenson’s considerations were of a different tenor. Thus, in fact, he wrote in 1891 to Mary Whitall Smith, his fellow student (as well as future wife), who was married at the time to magistrate Benjamin Costelloe: “I just can’t talk to Morelli, because he expects to be treated like a master.” The path, however, was set, and Berenson also began to develop, very early on, his connoisseur skills.

|

| Francesco Morandini known as Poppi, Madonna and Child (1561; oil on panel, 126 x 102.9 cm; Boston, Museum of Fine Arts) |

However, what was the method that Berenson, on the back of Morellian studies, had begun to develop? The scholar, as anticipated, started precisely from Morelli, seeking to study with the latter’s method the works of Lorenzo Lotto, the first artist to whom Berenson devoted himself totally. He therefore began to examine, work by work, the production of the Venetian artist, with the aim of finding connections and resemblances, even in the most minute and apparently insignificant details, that would allow him to reconstruct the training, the influences received, and the relationships between Lotto and other artists. This allowed him to go so far as to argue, contrary to Morelli’s view, that Lotto had been a pupil of Alvise Vivarini (Morelli, on the other hand, believed him to have been a disciple of Giovanni Bellini: although there is very little information on Lorenzo Lotto and it is not possible to arrive at certainties, today we tend to reward Berenson’s view). However, Morelli’s method was not considered sufficient; Berenson had therefore begun to refine, improve and expand it, and the results of his research were published in an essay entitled The rudiments of connoisseurship, which came out in 1902 but whose composition dated back to 1894. The main limitation of the Morellian method, that of so-called “sigla motifs,” was that it led the connoisseur to dwell too much on the details, leaving out the general aspects of the work, its essential features. Berenson noticed this, and while never mentioning Morelli in his essay, he actually proposed an update of the Morellian method. The morphological features of the elements of the work, those that Morelli had already identified as distinctive features of an artist’s hand, for Berenson had to be separated “from the artist’s feeling, from his spirit.” And in order to understand the artist’s “feeling,” the art historian could only appeal, according to Berenson, to the"sense of quality,“ which became the highest criterion for evaluating an artist’s work or, in Berenson’s words, ”the most essential tool for anyone who wants to be a connoisseur,“ as well as ”the point of reference for all the documentary and historical evidence collected and for all possible morphological tests conducted on a work of art."

However, Berenson was aware that “the discussion of quality is not about the field of science,” and concluded his essay by merely asserting that "we have not even mentioned the art of connoisseurship": a concept that would remain constant in Berenson’s criticism is that the art historian’s knowledge is never fully and strictly scientific. However, motif-symbol analysis alone may suffice when dealing with works for which a demonstration may be taken for granted: such is the case with a Madonna and Child with St. John that entered the New York Metropolitan in 1927 as a work by Antonello da Messina, an attribution widely accepted by many critics (including high-level ones such as Adolfo and Lionello Venturi). For Berenson, on the other hand, it was not a work by the Sicilian master, and to reach that conclusion the scholar believed that “the most tangible, the most obvious, the least subjective, the methods, I say, almost purely quantitative methods of archaeology, suffice if they do not even advance” (in 1941 in fact the work was later assigned to Michele da Verona). But Berenson also argued, as he wrote in one of his own essays dating precisely from 1927, that a problem of attribution “cannot be dealt with by dialectic and taste alone. It must be experienced and lived, tried and felt. [...] But precisely to such a vital substratum, the mere medium of words does not reach. The most obvious and real evidence stands before us, and it is finally stronger than any argumentation.”

|

| Michael of Verona, Madonna and Child with St. John (c. 1495-1499; tempera and oil on panel, 73.7 x 57.8 cm; New York, Metropolitan Museum) |

As early as 1897, in his book The Central Italian painters of the Renaissance (“I pittori del Rinascimento nell’Italia centrale”), Berenson, in the wake of the theory of pure visibility and thus approaching formalist criticism, had introduced the two concepts of"decoration" and"illustration.“ By ”decoration,“ Berenson meant ”all those elements which, in a work of art, appeal directly to the senses, for example, colors and hues, or which directly stimulate certain sensations, for example, form and movement.“ Instead, ”illustration,“ would be understood to mean ”anything in a work of art that draws our attention not because of an intrinsic quality contained in the work, but because of what it represents, either in outward reality or in someone’s mind." A badly colored and hastily drawn portrait may still remind us of a real person who actually exists: in such a case the work would be lacking in everything that contributes to its intrinsic quality (and thus would be lacking in decoration), but it could be an excellent illustration in that it can immediately call to mind the subject represented. In the field of “decoration,” Berenson would later bring in a concept central to his method: the so-called"tactile values," of which he would provide an interesting definition in his 1948 work Aesthetics, ethics and history in the arts of visual representation (“Aesthetics, ethics and history in the arts of visual representation,” translated into Italian by Mario Praz). Berenson wrote, “Tactile values are found in representations of solid objects when they are not merely imitated (no matter how truthfully) but presented in a way that stimulates the imagination to feel their volume, weigh them, realize their potential strength, measure their distance from us, and that encourages us, again in the imagination, to put ourselves in close contact with them, to grasp them, embrace them or go around them.” Tactile values, along with movement, are thus the qualities that allow a depicted object to be perceived as existing. Berenson believed that Giotto was a “supreme master in stimulating tactile consciousness.” This is because, according to Berenson, Giotto was able to achieve what the painter must achieve, which is the construction of the third dimension. And to do this, the painter can do no more than confer “tactile values on the impressions of the retina” and “excite the tactile sense.” In other words, when we stand in front of a work, according to Berenson we must have the illusion of being able to touch the figures depicted in it (hence the reason for the adjective “tactile”), which must then be able to provide, to us who observe, strong and effective sensations.

To give a better idea of what has been said, Berenson, in one of his major masterpieces(The Italian painters of the Renaissance, “I pittori italiani del Rinascimento,” first published in 1930), made a comparison between Cimabue ’s Maestà di Santa Trinita and Giotto’s Madonna di Ognissanti, the two large panels that hang together in the Uffizi. For Berenson, there would exist a profound difference between the two paintings, a difference “of realization”: looking at Cimabue’s work, the scholar argues, “we end up concluding” that the lines and colors “are intended to represent a seated woman, with men and angels standing or genuflected around her,” but to arrive at this identification “we had to make a much greater effort than the actual things and people would have required of us,” because the ability to evoke tactile sensations in Cimabue is inferior to Giotto’s. In fact, Berenson continues, looking at the Madonna of All Saints “the eye has barely had time to rest on the painting, which already realizes it in every part,” and “our tactile imagination immediately comes into play.” The essay then lists the elements that would enable Giotto to evoke these sensations, and subsequently argues that Giotto’s main merit lies in his greater ability, compared to Cimabue, to render tactile values (and the rendering of tactile values for Berenson is “the supreme quality”): for these reasons Giotto would have ensured a significant contribution to the development of painting.

|

| Left: Cimabue, Majesty of Santa Trinita (c. 1290; tempera on panel, 385 x 223 cm; Florence, Uffizi). Right: Giotto, Madonna of All Saints (c. 1310; tempera on panel, 325 x 204 cm; Florence, Uffizi) |

|

| Giovanni Bellini, Santa Giustina (c. 1470; tempera on panel, 129 x 55 cm; Milan, Museo Bagatti Valsecchi) |

Berenson’s method also had limitations, however: the scholar was in fact convinced thatstylistic analysis, the one on which his method was based, was clearly superior to investigations that took into account the historical and social context as well as documents, written sources, and other types of evidence that did not directly deal with images. On the contrary: for Berenson, methods based on philology and document study were unacceptable. This is what he wrote in the essay Aesthetics, ethics... which we quoted earlier: “What is most objectionable in the way Germanic-minded critics study art is that this study is cultivated either by philologists, with methods that have come to be formed in the study of texts, inscriptions and documents, or by historians who use the work of art only as a subsidy to reconstruct the past. These methods are out of place in the study of works of art created in periods about which we do not lack information, and still existing in the original. Like all things out of place, these methods bear great annoyance. They succeed only in burying the work of art under piles of junk.” For Berenson, every element that comes between the work of art and its user (including documents and sources) ends up altering the latter’s perception. However, Berenson’s method was certainly not immune to error. One example is the famous case of the so-called"Sandro’s Friend," a fictitious name Berenson invented to find the possible author of a group of paintings variously attributed to Sandro Botticelli, Filippino Lippi and other authors contemporary with them, but which, according to Berenson, had common features that could have suggested the existence of a single, unknown hand that would have painted them. The scholar even went so far as to outline a kind of psychological profile of the alleged artist, without bothering to give weight to the sources: it was, in short, an attempt to construct an art history whose framework was solely supported by the analysis of images. The insubstantiality of this “Sandro’s friend,” and the forcings Berenson had put up to justify it, were highlighted above all by Herbert Horne, the scholar who more than any other was concerned to dismantle, systematically and convincingly, Berenson’s thesis, who then rejected his own idea in 1932. The fact remains that Berenson was one of the most influential scholars of his time and, as was the case with other art historians of his time, many of his attributions still endure today.

Reference bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.