by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta , published on 17/09/2018

Categories: Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

Carl Burckhardt was a great admirer of Auguste Rodin's work: his sculpture was affected and he also dedicated a book to the French sculptor. This relationship is the subject of the article.

“He is truly a wonderful devotee of the beautiful”: Auguste Rodin according to Carl Burckhardt

“At the Kunsthalle a pair of torsos and a woman lying in plaster, fragments of giants, representations of crowds, everything that falls under the concept of ’monumental’ [...] are temporarily visible. He seems to mold the material continuously, night and day, without a precise design, and then suddenly, like a revelation, here is the work appearing in its crystalline monumentality.” It was in 1906 when Carl Burckhardt (Lindau, 1878 - Ligornetto, 1923), a great artist considered by many to be the father of modern Swiss sculpture, went to the Basel Kunsthalle to visit an Exposition d’art française in which a number of sculptures by Auguste Rodin (Paris, 1840 - Meudon, 1917) were on display, among others. The above excerpt is written in the aftermath of the visit: it is taken from a letter Burckhardt sends to his friend Hermann Kienzle, and it contains all his enthusiasm for discovering Rodin’s works, which the Swiss sculptor finally got to observe in depth and not superficially for the first time. Obviously, Burckhardt was already familiar with Rodin: impossible, for an up-to-date artist like him, not to be aware of who was what at the time was the most famous and appreciated sculptor in France. Nevertheless, even the Lindau artist had joined the ranks of those who had despised certain works by Rodin: in that same letter of March 25, 1906, Burckhardt goes on to call a work such as Celle qui fut la belle heaulmière “disgusting” and a “bogeyman” the monument to Balzac (later, as will be seen below, Burckhardt’s attitude would undergo major transformations).

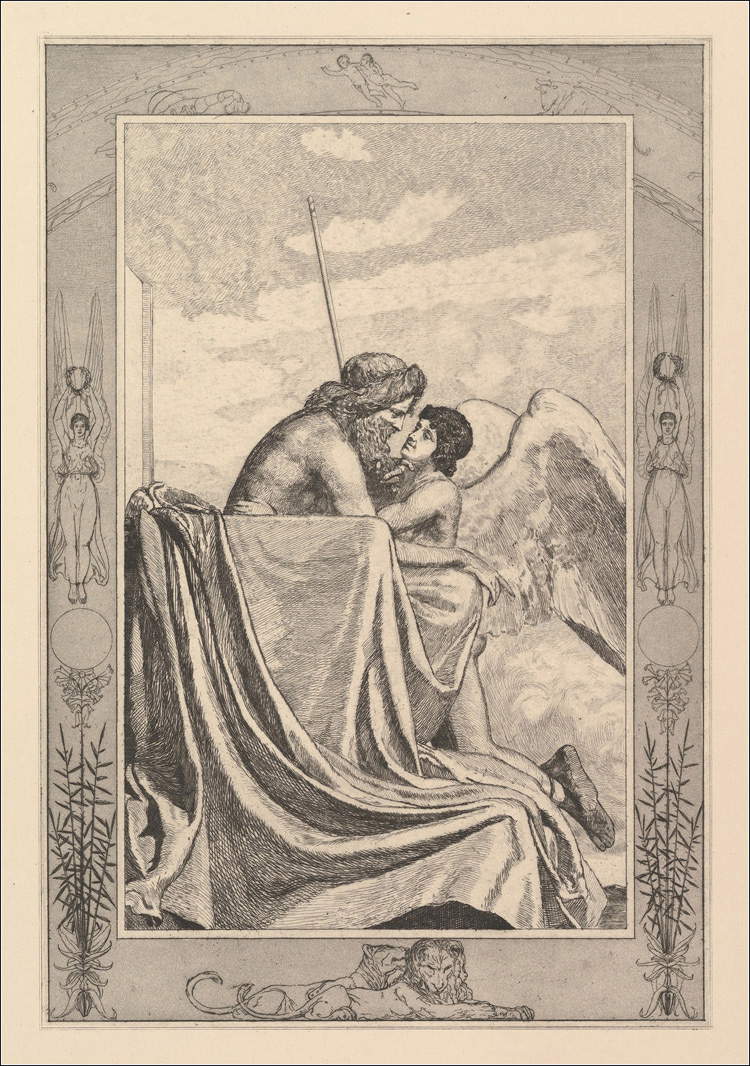

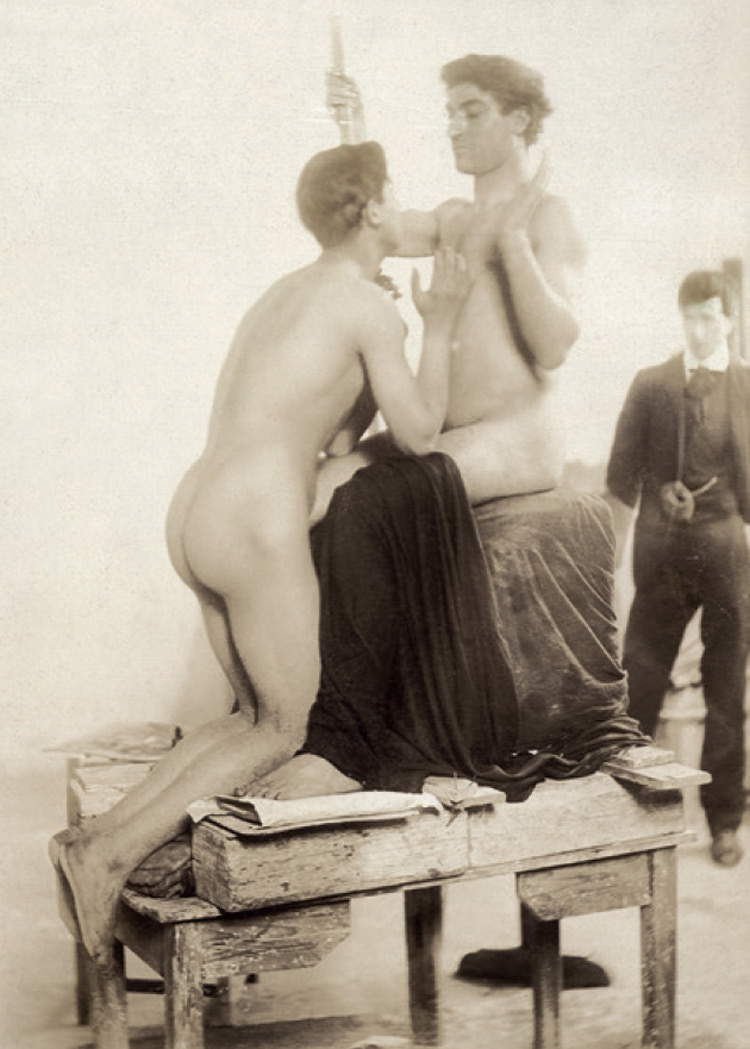

But in the letter to Kienzle the sculptor also indulges in considerations of the opposite kind: “since yesterday,” we read, “I have been feeling buoyed (and not puffed up!) by a breeze that with good hope will carry me on pleasantly for years: [...] Rodin [...] is indeed a marvelous devotee of the beautiful, before whom for me now almost everything disappears,” where the “everything disappearing” are certain works such as, precisely, the Heaulmière and the monument to Balzac, toward which Burckhardt continues to feel a kind of revulsion. In order to better frame the artist’s judgment, it is necessary to consider the course of his art: a few years before the Kunsthalle exhibition in 1903, Burckhardt, then 25 years old, had abandoned the idea of creating a work now recognized as one of his youthful masterpieces, the Zeus and Eros on which he had begun to reflect as early as 1901, during a stay in Rome. The idea was to give form to a moment in the fable of Cupid and Psyche, the one during which Eros (or Cupid, whatever), toward the story’s final lines, goes to his father Zeus (Jupiter to the Romans) to ask him to consent to his union with Psyche (a purpose to which Zeus will not object: the fable ends with the marriage of Cupid and Psyche). To make his sculpture, which was later left unfinished, Burckhardt had hired two local models, Caesar and Baptist, and had them pose for his masterpiece: in the work we see the two figures placed facing each other, with Eros kneeling, elbows resting on his father’s thighs, and the latter seated on the throne, as he listens earnestly and in a hieratic pose to his son’s request. Burckhardt, while drawing heavily from the classical repertoire (as well as from the contemporary one: the most immediate antecedent is the engraving Amor und Psyche. Ein Märchen des Apulejus by Max Klinger), distorts the usual iconography that wanted Zeus depicted as a bearded old man and Eros as a young man, little more than an infant: Zeus is beardless and much younger than he should be, while Eros, on the other hand, is a young man already formed, so much so that the two seem almost the same age (a detail that, moreover, cloaks the group with a strong homoerotic charge). In a letter sent to his brother Paul on July 26, 1902, the artist declared that his aim was to conduct a “careful study of nature”: his youthful sculpture, in fact, starts out in the name ofadherence to reality (combined with a modeling of the surfaces animated by the search for pictorial effects), even in the wake of a lofty and dignified classicism that he derived from his study of ancient works and his passion for classicism (Burckhardt would stay for long periods in Italy). It is, moreover, on his relationship with classicism that much of the exhibition Echoes from Antiquity was based. Carl Burckhardt (1878-1923). A Sculptor between Basel, Rome and Ligornetto, the first comprehensive retrospective devoted to Burckhardt, at the Vincenzo Vela Museum in Ligornetto, Canton Ticino, from June 10 to October 28, 2018.

A further development is marked by the Venus conceived and realized in Basel and Forte dei Marmi between 1905 and 1909: Burckhardt aimed to create a life-size sculpture of the mythological goddess of love, inspired by the classical iconography of the Venus anadiomene, or Venus emerging from the sea. Again, however, Burckhardt provides an original and personal interpretation of the theme, making a Venus not intent on running her hands through her hair, as per typical iconography, but with her hands crossed at neck level, and with her legs veiled. We also preserve the preparatory models of the work, and analyzing them we can see how Burckhardt went from a figuration that was decidedly adherent to the real thing (Charlotte Schmidt-Hudtwalcker, a friend of his wife Sophie Hipp and wife of Carl Schmidt, professor of geology at the University of Basel, had posed for him) to a final drafting in which the “realistic rendering of the nude model,” the artist himself writes, gives way to an “ideal appearance of the classical goddess of love, creating a work of art in its own right.” The final version of Venus is a composite work, in different materials (the body is white Apuan marble, the veil is purple marble, while for the hair the sculptor opts for onyx), whose volumes are more plastically compact than those of the initial models, so much so, scholar Tomas Lochman points out, that the features of Charlotte Schmidt-Hudtwalcker are no longer discernible in the finished sculpture (however, the University of Basel reportedly refused to exhibit the work in its museum: it considered it disreputable to show a sculpture for which a lecturer’s wife had posed nude ).

|

| Auguste Rodin, Celle qui fut la belle heaulmière (1887; bronze, 50 x 30 x 26 cm; Paris, Musée Rodin |

|

| Auguste Rodin, Monument to Honoré Balzac (1898, cast 1935; bronze, 270 x 120.5 x 128 cm; Paris, Musée Rodin - gardens) |

|

| Max Klinger, Amor bei Jupiter, panel 14 from the collection Amor und Psyche (1880; engraving on paper, 25.55 x 17.30 cm; Portland, Portland Art Museum) |

|

| Carl Burckhardt, Zeus and Eros (1901-1904; clay model of the entire group; destroyed in 1904) |

|

| Carl Burckhardt observes models posing for the sculpture Zeus and Eros. Photograph circa 1902. © Nachlass Carl Burckhardt |

|

| Carl Burckhardt, Venus (1908-1909; various marbles, height 191 cm; Zurich, Kunsthaus) |

|

| Carl Burckhardt in the atelier in Arlesheim next to the second clay model for Venus. In the background the remains of the first model. 1907 photograph. © Nachlass Carl Burckhardt |

Rodin’s discovery occurred during the very years Burckhardt was working on Venus. For Burckhardt, this was a decisive moment: as Lochman again points out, his interest in Rodin “enabled him to free himself from that process of stylization and pictorial animation of natural forms that characterized his early production”: “all his creative tension is now aimed at freeing his sculptures from their outer shell, at capturing the intimate substance of the bodies, at bringing out the plasticism of their elementary forms, the ’pure plasticism’ as he himself defines it.” This maturation in an exquisitely plastic sense of Burckhardt’s sculpture would come in the 1910s: the models of reference are the works of the French artist’s late maturity, those of the last two decades of his life, those that seem to be left in a state of unfinishedness, those that see figures emerging from marble but at the same time almost locked in pure matter, those animated by the presence of twisting bodies. Works such as Fugit Amor of 1889, where “the figures modeled by Rodin float in the infernal storm but are at the same time firmly anchored to the ground by the base from which they seem to emerge,” declaring “their condition as other than life, highlighting their nature as figures that exist only in sculpture” (Flavio Fergonzi), or even works such as the circa 1898 Amore e Psiche group preserved at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, where the two protagonists are locked in an embrace that also seems to be captured by the marble from which the lovers rise, or such as the 1899 Psyche that catches the young woman at the moment when, hidden under a cloak, she tries to spy on Amore as he sleeps.

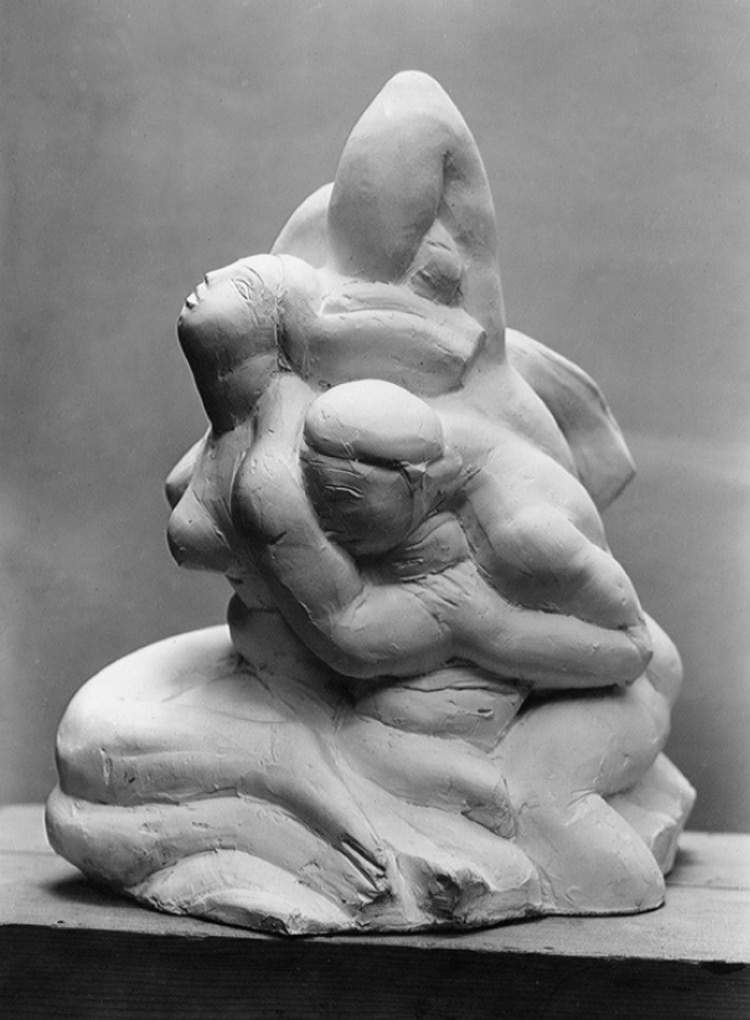

Burckhardt’s rapprochement to the ways of the last Rodin is especially recorded in a sculpture probably made in 1916 (we do not know the date with certainty): it is a Kidnapped Woman, a group in which the protagonist tries to escape a man who is chasing her. A very strong sculpture: the woman, naked, is on her knees and trying to wriggle out of the grasp of the man who grabs her from behind and is about to overpower her. The composition is based on a pyramidal structure like many of Rodin’s works belonging to the aforementioned case in point (and examples of this are precisely the Love and Psyche group and the Psyche): the apex is the elbow of the man, who is caught trying to brutally bend the woman with his right arm. In contrast, the legs of the protagonists, as in Rodin’s sculptures seem almost trapped in the plinth, and at the same time the forms become more essential and soft and blend together, another element inferred from Rodin’s sculpture. This tendency would later lead Burckhardt to a further simplification of forms, which can be grasped in other works of the 1910s: illustrative in this sense are the Seated Woman, also made perhaps in 1916 (the original plaster cast is preserved, but the known castings are all posthumous), and the Resting Shepherdess, conceived in the same period. Both works, as well as all the others sculpted in those years, are united by the intent to subject forms to a total stylization, which concerns not only bodies but also elements such as clothing or objects (this is the case with the Shepherdess), and which sometimes goes so far as to make some details take on the appearance of pure geometric forms. However, his interest inclassical art is not diminished: the Basket Bearer, of 1918, although subjected to that simplification that Burckhardt now insistently seeks, has the fixity and dignity of an ancient caryatid.

|

| Auguste Rodin, Fugit Amor (1885; marble, 60.5 x 102 x 42.5 cm; Paris, Musée Rodin) |

|

| Auguste Rodin, Cupid and Psyche (c. 1898; marble, height 101 cm; London, Victoria and Albert Museum) |

|

| Auguste Rodin, Psyche (1899; marble, 73.66 x 68.58 x 38.1 cm; Boston, Museum of Fine Arts) |

|

| Carl Burckhardt, Abducted Woman (1916?; plaster cast from clay model, height 41.5 cm; Basel, Kunstmuseum) |

|

| Carl Burckhardt, from left: Seated Woman (1915-1916?, 1974 posthumous casting; bronze, height 36 cm; Private Collection), Shepherdess Resting (1917-1918; bronze, height 42 cm; Basel, Kunstmuseum), Basket Bearer (1918, posthumous casting; bronze, height 87.5 cm; Basel, Kunstmuseum) |

Burckhardt’s passion for Rodin would endure over the years, leading him first to publish, in 1917, an obituary on the occasion of the French artist’s death, then to organize and curate, in the same year, a retrospective on Rodin at the Basel Kunsthalle, and finally to publish, in 1921, an important book entitled Rodin und das plastische Problem (“Rodin and the Problem of Sculpture”). For Burckhardt, the “center of the problem” is “the struggle for the approximation of the complex forms of nature to the simplest spatial forms.” Within this struggle, Rodin is seen as the innovator who embarked on the path of purifying sculpture by opening a new era for art. Burckhardt analyzes Rodin’s work from an eminently evolutionary perspective (a perspective that Rodin studies today has abandoned, preferring instead to evaluate the different stages of his career from a perspective that takes into account the different aspects of his artistic personality and their co-presence throughout his activity: for example, the centenary exhibition of his death, organized at the Grand Palais in Paris in 2017, took this point of view) dwelling on many of the artist’s masterpieces to grasp their influences, traits of originality and innovative elements. “The highlight of the volume,” according to critic Felix Ackermann, who dedicated an essay to Burckhardt’s book in the scholarly publication presented on the occasion of the aforementioned exhibition at the Vincenzo Vela Museum in Ligornetto, is the chapter devoted to one of Rodin’s greatest masterpieces, L’homme qui marche. A work so important that Burckhardt tried to convince (and succeeded) the committee of the Basel Skulpturhalle to acquire a plaster copy of theHomme qui marche, which can therefore be admired today in the Swiss museum thanks to the sculptor’s solicitations.

“The greatest effect” Rodin achieved in theHomme qui marche, Burckhardt points out, “is the simple plastic form, the clear spatial structure represented by the legs and torso,” plus “the modeling of the surface gives way to volumetric articulation.” Again, another of the fundamental achievements of theHomme qui marche is its ability to free itself “from the incidence of light, which in the pictorial modeling of the surface is distributed in a unilateral and predetermined manner.” In short,Homme qui marche marks a new era for Burckhardt since, as he sees it, Rodin’s sculpture totally renounces light effects, which interfere with the purpose of seeking the purest forms. For Burckhardt, Ackermann notes, “the sculpture of the new era will have to go through a process of simplification, liberation and purification from any pictorial effects, with the goal of simple ’plastic form.’”

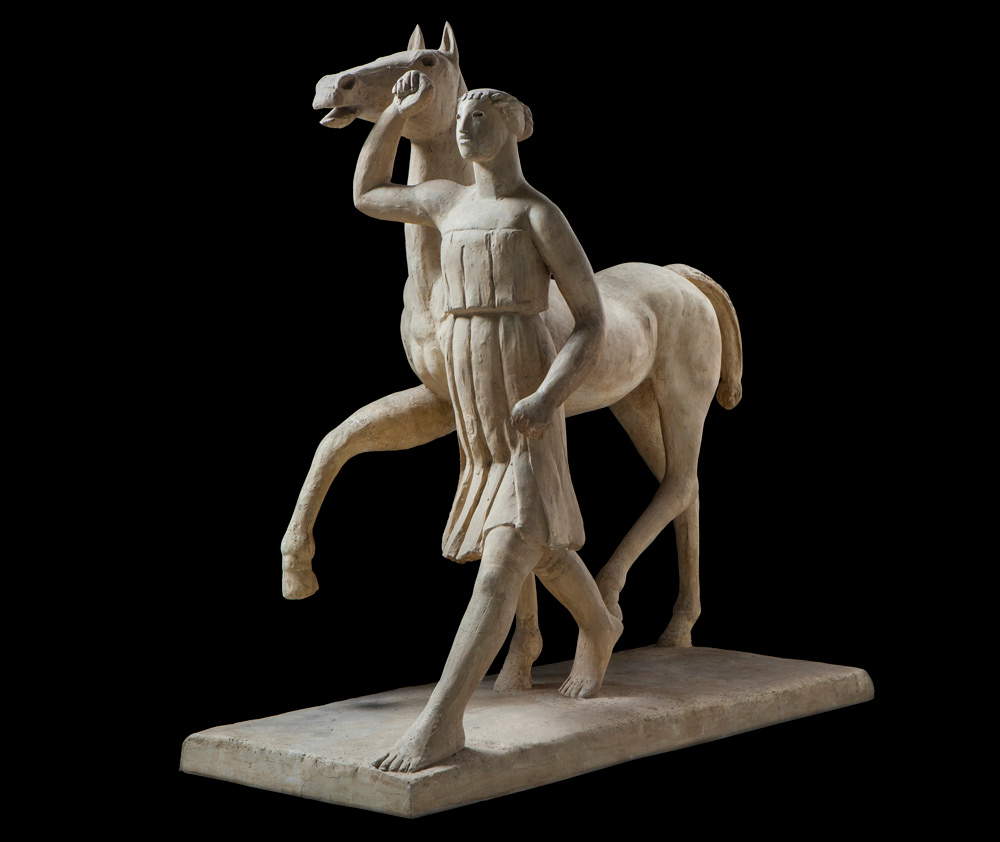

Ackermann then poses an important question, namely, to what extent does the book on Rodin contribute to the understanding of Burckhardt’s work. A first important example for answering the question is provided by the reliefs of the Amazons executed for the Kunsthaus Zurich (Burckhardt finished them in 1914 but had begun working on them as early as 1908): in these works, the scholar explains, “the surfaces are treated uniformly, whether it is the background, the bodies, the horses’ manes or the Amazons’ hair. As a result, manes and hair are abstracted, becoming mere volumes.” A similar form of abstraction can then be seen in the modeling of bodies: these are among the earliest examples of approaching the “simplification” of which Rodin had been a master, but in Burckhardt’s production it is possible to encounter other works whose dependence on the great French sculptor seems stringent. One thinks precisely ofHomme qui marche: the gait of the Rodinian man may have provided more than a cue for one of Burckhardt’s last works, theAmazon leading a horse, from 1923 (to create it, the artist, who was living in Ligornetto at the time, had even arranged to obtain a real horse so that he could study it closely). The work, also indebted to the Rosselenker (“The Man Leading a Horse”) by Louis Tuaillon (Berlin, 1862 - 1919), had been commissioned from him in 1918 by the Kunstverein Basel, which wanted to destine it for a public space: even in the case of theAmazon, Ackermann concludes, “the natural form has been forcefully transmuted into a simpler spatial form - forgoing the modeling of surfaces that Burckhardt would have described as pictorial.”

|

| Carl Burckhardt, The Five Metopes of theAmazonomachy (1913-1914; Bollingen sandstone, 270 x 300 cm each; Basel, Kunstmuseum, exterior wall of building) |

|

| Auguste Rodin, Homme qui marche (1907; bronze, 213.5 x 71.7 x 156.5 cm; Paris, Musée Rodin) |

|

| Louis Tuaillon, Der Rosselenker (1902; bronze; Bremen, Bremer Wallanlagen). Ph. Credit |

|

| Carl Burckhardt, Amazon Leading a Horse (1923; plaster cast from 1:1 scale clay model, height 231 cm; Basel, Skulpturhalle) |

The writing on Rodin and, even before that, the curatorship of the major exhibition at the Basel Kunsthalle also helped solidify Carl Burckhardt’s reputation as an art critic and theorist. In conclusion, one might wonder how much Burckhardt’s work, both sculptural and literary, affected the spread of Auguste Rodin’s posthumous fame. In fact, it is possible to evaluate sculpture and treatise from a unified perspective, since both the material and the written works combine to underscore the innovative character of Rodin’s sculpture (not to mention the fact that, as we have seen, they are closely related). This is also by means of radical changes of judgment on certain works: think of the monument to Balzac, which in the letter to Kienzle was labeled a “bogeyman,” and which instead in Rodin und das plastische Problem is called “probably Rodin’s most independent creation,” a clear symptom of his free temperament. Of course: as mentioned above, today a certain kind of analysis of Rodin’s production seems hopelessly outdated, and consider also that Burckhardt’s study is filled with personal observations, peculiar to a sculptor, and moreover to a sculptor who feels a very strong passion for the object of his study. However, it is also necessary to note how Burckhardt’s treatise succeeds in capturing several fundamental aspects of Rodin’s work, providing important guidelines for its understanding (starting, of course, from Burckhardt’s point of view and his attempt to solve the “problem of plastic form”). At the time, the book earned him numerous plaudits from critics (who credited Burckhardt above all for being the first to assess theHomme qui marche in the most appropriate manner), while today, Ackermann points out, the book “has a very specific meaning that transcends the subject of Rodin’s reception” and can be more accurately read as “the self-testimony of an artist grappling with an illustrious predecessor.”

Reference bibliography

- Gianna A. Mina, Thomas Lochman, Echoes from Antiquity. Carl Burckhardt (1878-1923). A sculptor between Basel, Rome and Ligornetto, Edizioni del Museo Vincenzo Vela, 2018

- Chiara Vorrasi, Fernando Mazzocca, Maria Grazia Messina, States of Mind. Art and Psyche between Previati and Boccioni, exhibition catalog (Ferrara, Palazzo dei Diamanti, March 3 to June 10, 2018), Ferrara Arte, 2018

- Andreas Röder, Rodin und Beuys: über das plastische Phänomen der Linie, Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2003

- Titus Burckhardt (ed.), Zeus und Eros. Briefe und Aufzeichnungen des Bildhausers Carl Burckhardt, Urs-Graf-Verlag, 1956

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.