Gustav Klimt's two "Italian" paintings, "The Three Ages of Woman" and "Judith II"

Women were depicted by Gustav Klimt (Baumgarten, 1862 - Vienna, 1918) in most of his paintings, being exalted now for their sensuality, now for their pride. The female body, far from hidden, becomes a symbol of seduction and maternal gentleness, characteristics that every woman possesses. Elements that also appear evident in the only two Klimtian works kept in Italy (if we make an exception for the female portrait stolen from the Ricci Oddi Gallery in Piacenza in 1997): the Judith II and the Three Ages of Woman, protagonists of an art that intends to represent on canvas every aspect of the feminine, from the woman-child to the woman-fatal, from carnal passion to motherhood and old age. In each case, a woman aware of her essence, her temperament, and her femininity. After all, the Austrian painter’s art is set in a time when sexuality and studies on it invaded every field of knowledge, especially in early twentieth-century Vienna, thanks to the medical and psychoanalytic contributions of Sigmund Freud (Freiberg, 1856 - Hampstead, 1939) and the literary contributions of Arthur Schnitzler (Vienna, 1862 - 1931). Fundamental contributions that transcended conventions and bourgeois respectability and made nudity a natural aspect of being human, aimed at greater knowledge and awareness of one’s body.

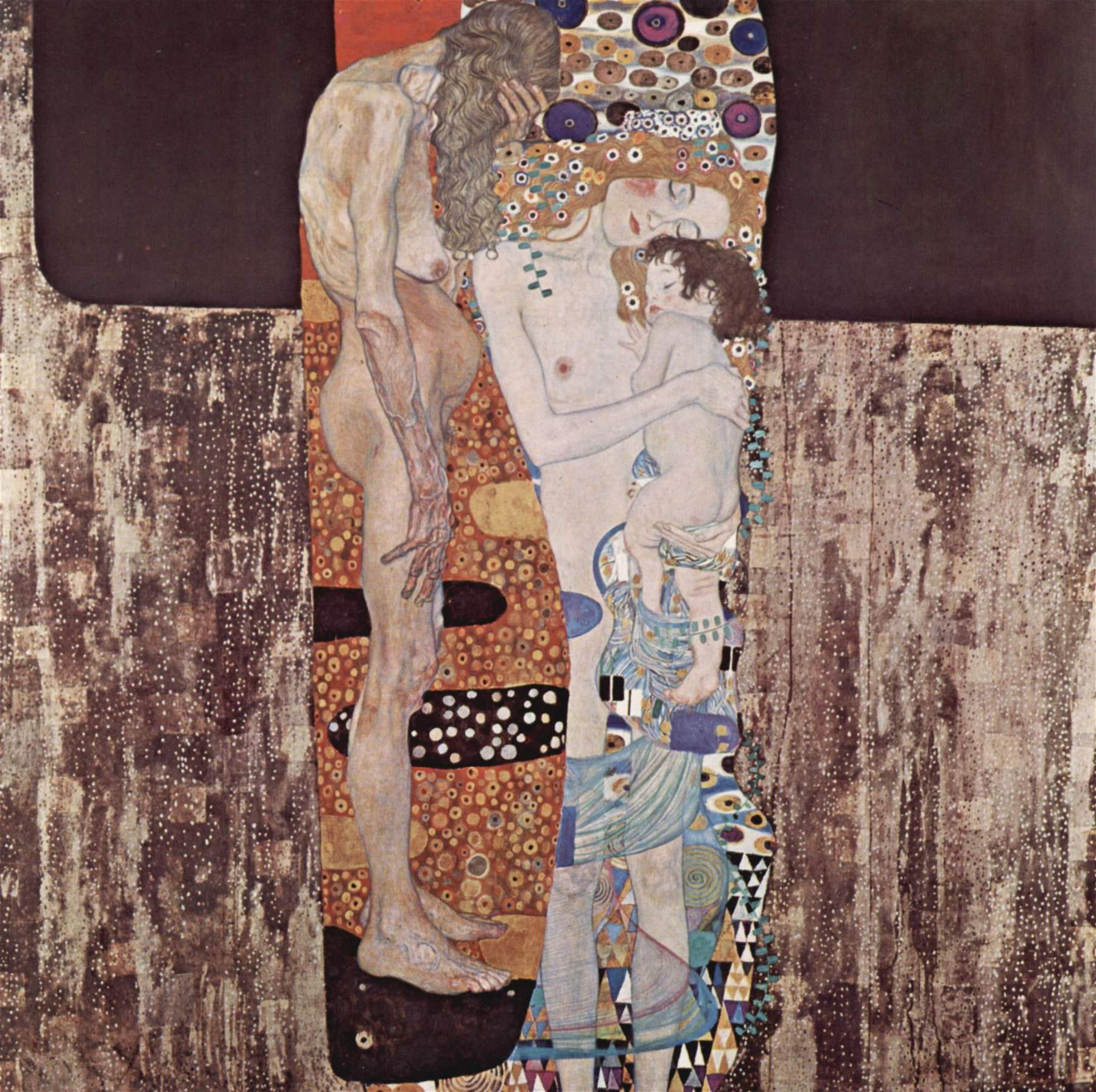

Indeed, nudity recurs in Klimt’s female figures, from those in their infancy to the more mature: this is unmistakably evident in the famous oil on canvas The Three Ages of Woman, preserved at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome, to which it was destined after the Italian state acquired it in 1911. It is a work that traces side by side the three phases of a woman’s life: the right-hand side depicts a young woman frontally holding a little girl in her arms, clutching her, while the left-hand side depicts an elderly woman in profile. The two cores of figures seem at the same time close but distant, since in addition to being painted from different viewpoints, their respective backgrounds are also different; however, they are placed in one central core to presumably signify a kind of temporal succession inherent to the course of life. The little girl and the young woman are tenderly embraced, as a mother does with her daughter; they are both naked, so that each feels the warmth of the other’s body and each lives by that warmth, by this immeasurable love. Both of them keep their eyes closed, as if to fully enjoy this intimate maternal moment, and a great sense of tenderness shines through as the two faces approach each other, both of them relaxed and relaxed, as well as slightly flushed on the cheeks, probably to highlight that warmth mentioned earlier.

|

| Gustav Klimt, The Three Ages of Woman (1905; oil on canvas, 180 x 180 cm; Rome, National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art) |

|

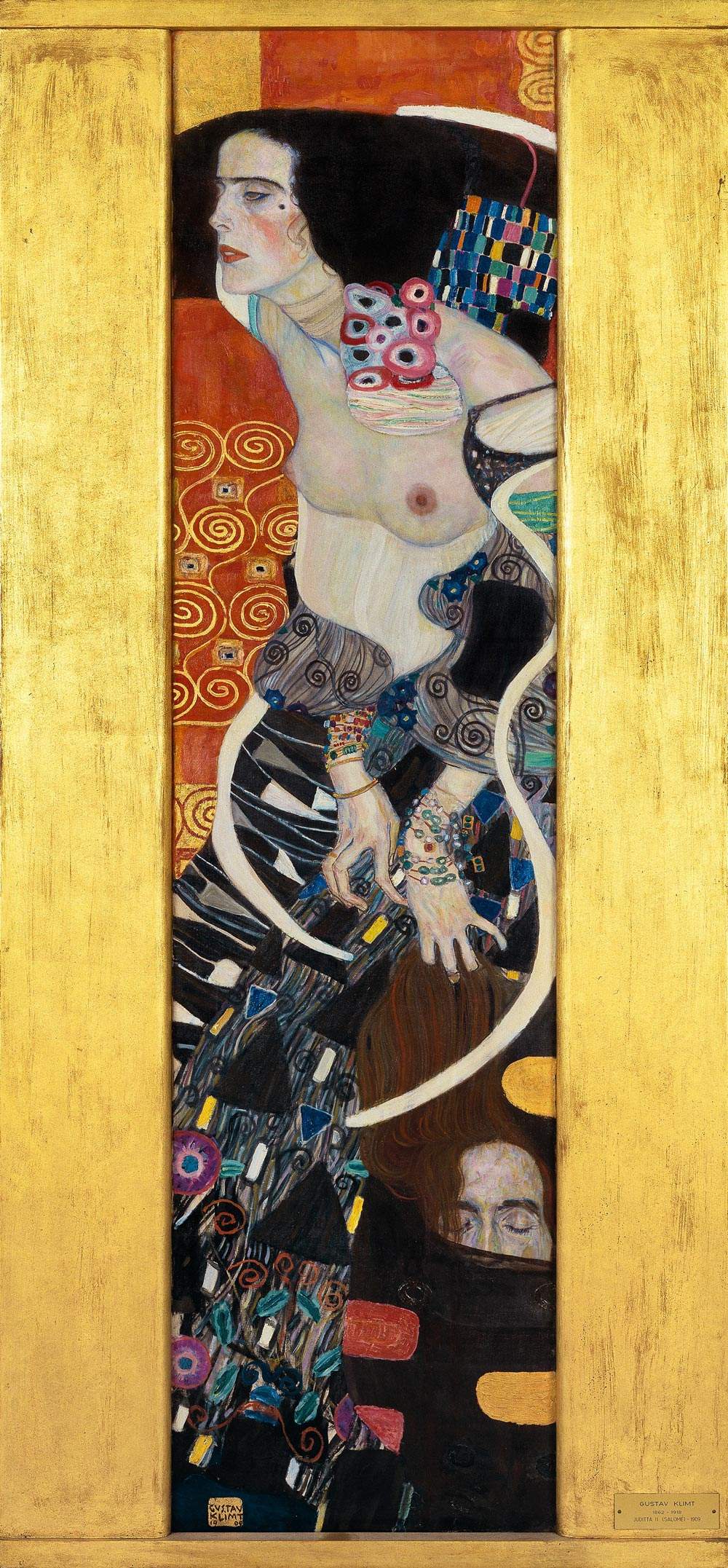

| Gustav Klimt, Judith II (1909; oil on canvas, 178 x 46 cm; Venice, Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna di Ca’ Pesaro) |

The older woman is placed in profile toward the two figures mentioned above, with whom the only visible contact appears to be between the former’s hair and the younger woman’s red hair and right shoulder. The older figure’s face is hidden by the curly, gray hair that falls over her breasts, and in addition she further covers her face with one hand. Her body is marked by age and past motherhood: the skin seems almost weathered and wrinkled, the frame is gaunt and curved, the breasts have lost their solidity, and the pronounced belly indicates a distant pregnancy. Another detail to note is the difference between the women’s respective hands: that of the elderly woman is characterized by a visible roughness with thin, gnarled fingers; more delicate, smooth, and white those of the young mother, with which she holds the child. The latter’s small hand tenderly pokes out under the small chin to rest on the mother’s breast.

The closeness of the more mature figure to the other two indicates a desire for physical and emotional presence, but with her position it is as if she wants to leave room for the younger ones, who have a whole life ahead of them, yet to be fully enjoyed, while she is moving toward decline. Indeed, they underscore fertility by the flowers encircling the mother’s head and falling over her shoulders; her legs are also wrapped in a thin, light blue veil that also partially envelops those of the child: perhaps indicating the close and inseparable bond that unites the latter.

Regarding the respective backgrounds, which are visibly different, it could be said that a sense of vitality and fertility pervades the decorations in which mother and daughter are immersed: a field of colorful flowers of small to medium size and bright colors; on the other hand, on a somewhat golden and somewhat black background is placed the elderly woman, probably indicating an age in which life (with small flowers of the same dull tone) and the thought of death (where there are no more flowers) coexist. Significant in this sense is the surface on which the latter’s feet rest: straddling a kind of line, one is placed in the golden area, while the other, the outermost one, is placed in the black-colored area with no flowers, no life forms. As if straddling the line between life and death. The hand brought to his face could be in this sense a sign of sadness for his existence almost coming to an end.

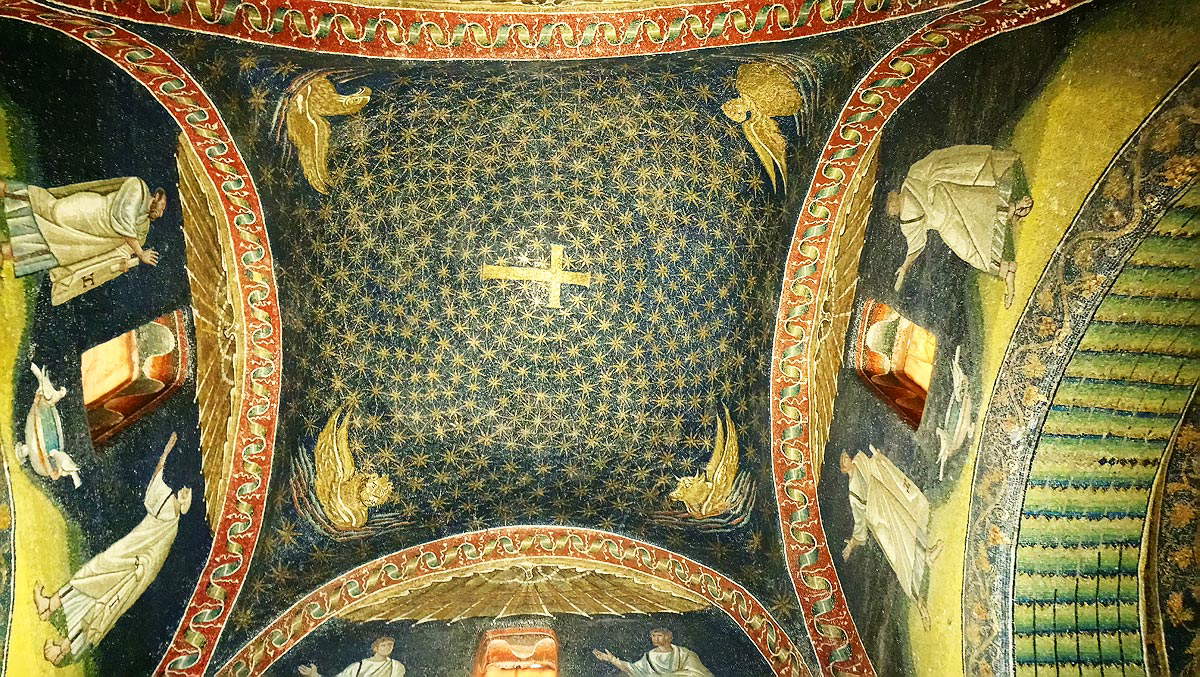

Influential for the decorations that serve as a backdrop for the three women was Klimt’s 1903 trip to Ravenna, in the land of mosaics: in the Austrian painter’s paintings, the ornaments refer, both in color and composition, to the mosaic technique. The artist felt incredible amazement when he visited the Basilica of San Vitale and all the other places in Ravenna where Byzantine taste produced wonderful masterpieces, still admired and loved by thousands of people, in which blue, green and gold create elaborate but precise and defined compositions. Very similar, in this writer’s opinion, to the ornamental backgrounds of this Klimtian painting is the barrel vault and dome with floral and star motifs of the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia.Ravenna’s inspiration gave rise to celebrated masterpieces of his, featuring both these multicolored, floral motifs and the golden mosaic tesserae from which sprang the "golden period" of his production. The painting of The Three Ages dates from 1905, just two years after his trip to the Romagnola city; it was exhibited in the room set up with works by Klimt at the 1910 Venice Biennale , along with the 1909 Judith II, now in the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Venice (it was purchased by the City of Venice in 1910).

|

| Ravenna, Mosaics in the Basilica of San Vitale. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Ravenna, Mosaics of the vault of the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia |

|

| Ravenna, Mosaics of the dome of the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

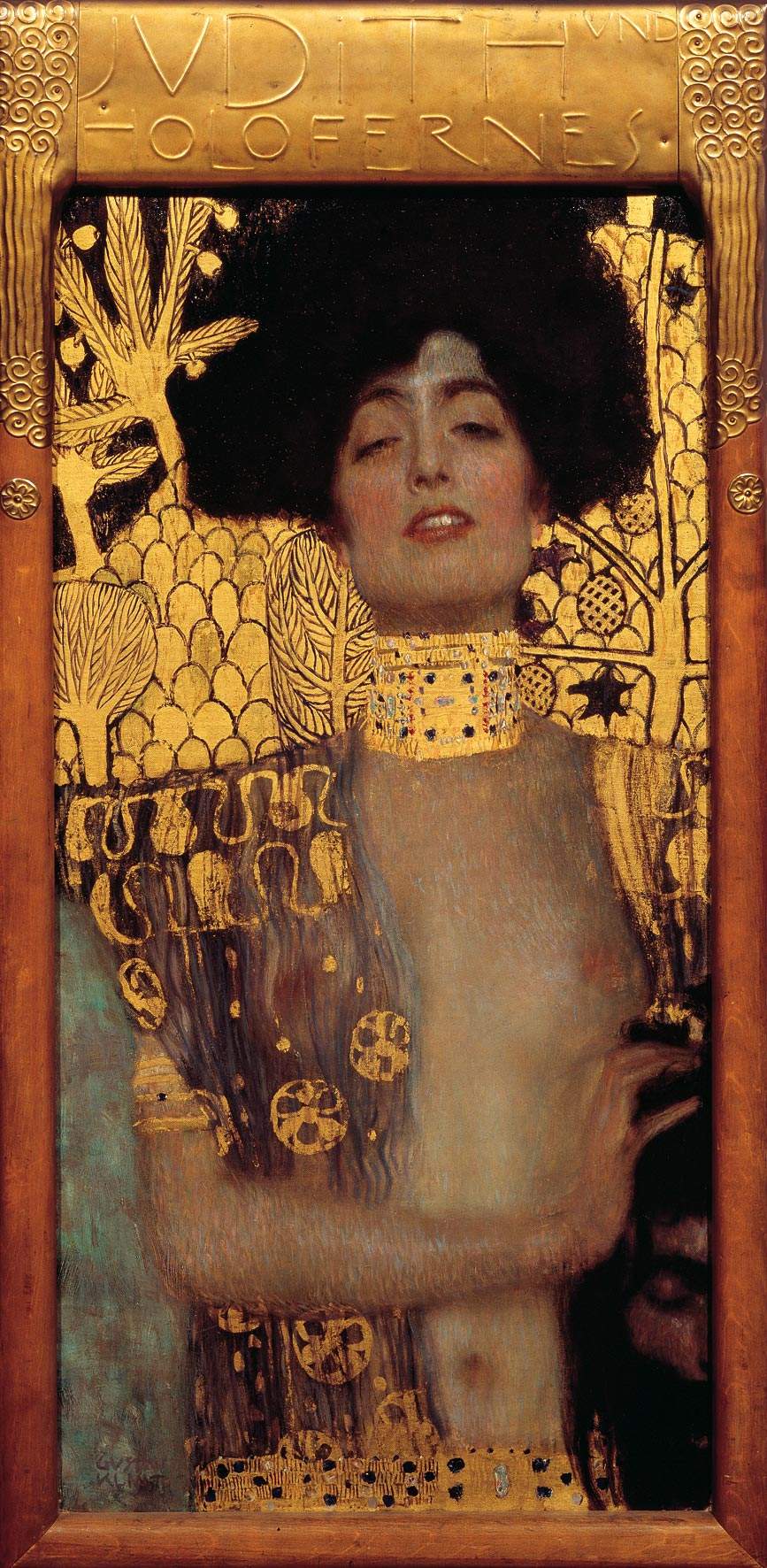

The artist had already depicted on canvas thebiblical heroine, who became a symbol of female strength and courage and of revenge against male abuse: the beautiful young Judith managed to save her Jewish people by seducing the Assyrian general Holofernes, who had besieged the opposing territory, and finally killing him by cutting off his head. Klimt completed Judith I, now housed in the >Österreichische Galerie Belvedere in Vienna, in 1901. It is a work charged with sensuality and eroticism that shines through the body and gaze of the female figure: the robe that lets the exposed breasts show and the winking gaze captivate the viewer; it is a femme fatale that one finds before one. Holofernes’ head is half glimpsed in the lower right corner, held by the woman’s hair in a gesture that resembles a caress, but actually conceals a murderous act. It is thought that the artist, in creating this painting, took as his model Adele Bloch-Bauer, a woman of high society in Vienna, whose portrait he painted in 1907.

The characteristic slender, almost monumental figure that lends sensuality to Klimt’s women also persists in Judith II , but unlike the earlier Judith, this one is depicted in profile and with more curved lines, giving the impression that the heroine is sitting with her legs to one side. Her gaze is not turned toward the viewer, and her breasts are entirely uncovered without any garments on her torso; a decoration with geometric motifs envelops her from the belly down, leaving out only her hands. With a hand full of gem-studded bracelets she holds dangling by her long hair the head of General Holofernes, whose face can be glimpsed with finer, more carefully groomed features than the one portrayed in Judith I. Indeed, the latter had a rougher appearance, with a thick beard and thick hair. Note the fact that in Judith II the severed head appears to be introduced in a black sack, as in fact the biblical heroine did with the help of her handmaiden to escape from the tent of the Assyrian general. An element that should give pause for thought about the attribution of the subject depicted: this painting has in fact been juxtaposed in many cases with the depiction of Salome, another biblical woman linked to the beheading of a man, but on that occasion the head of St. John the Baptist was carried on a tray.

|

| Gustav Klimt, Judith I (1901; oil on canvas, 84 x 42 cm; Vienna, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere) |

|

| Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907; oil on canvas, 138 x 138 cm; New York, Neue Galerie) |

|

| Assyrian Art, Reliefs of Lachish, detail (c. 700 B.C.; plaster; London, British Museum) |

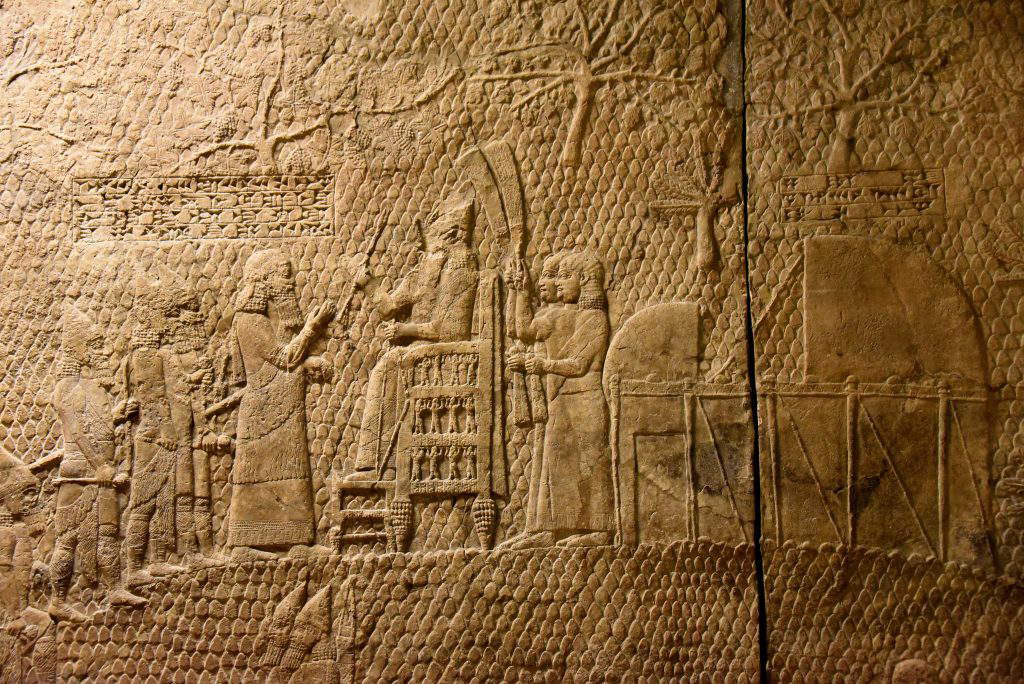

The backgrounds of the two versions of Judith are also markedly different: in the first, a stylized landscape with trees and hills can be seen that is completely gilded, a quotation from an Assyrian relief from the Palace of Sennacherib in Nineveh (and now in the British Museum). In this canvasgold is the predominant color, which in addition to the landscape invades with circular ornaments the transparent robe and the luxurious Art Nouveau collar, as well as the very frame made by the artist’s brother, Georg (Vienna, 1867 - 1931), a sculptor and chiseler. The decorations of the second one present, as already stated, geometric motifs ranging from spiral, triangle and rectangle; here, moreover, gold frames the pictorial composition that features alternating blacks, yellows, reds, purples, whites and blues.

Gabriella Belli, curator of the exhibition Around Klimt. Judith, Heroism and Seduction , which was held in Mestre from December 2016 to March 2017, wrote in the exhibition catalog: “Judith will go back through the centuries to the age of Klimt, gradually stripping in literature, poetry and art of her chastity, her virtue and the fortitude that had sustained her in the ordeal of her extreme act of heroism, in a negative inversion of the myth that will be precisely sung by Klimt in the magnificent 1909 painting. What the Viennese master shows us is no longer a heroine of history, she is not a savior, she is not chaste, rather she is a woman who has discovered her own sexuality, who rejects her social marginality, who has descended the darkness of the unconscious by discovering her own innermost drives, even those related to the desire to give death.”

The women protagonists of the mentioned works by Klimt represent in their attitudes and poses the Viennese culture of the early 20th century, yet making evident the influences the artist had from Italy, from the famous monuments of Ravenna. Works where painting and mosaic coexist on extraordinary and striking canvases that have become masterpieces of art history.

Reference bibliography

- Dani Cavallaro, Gustav Klimt. A Critical Reappraisal, McFarland, 2018

- Gabriella Belli (ed.), Around Klimt. Judith, Heroism and Seduction, exhibition catalog (Mestre, Centro Culturale Candiani, December 14, 2016 to March 5, 2017), Linea d’Acqua, 2016

- Patrick Bade, Gustav Klimt, Parkstone International, 2011

- Robert Weldon Whalen, Sacred Spring: God and the Birth of Modernism in Fin de Siècle Vienna, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2007

- Eligio Imarisio, Woman then artist: identity and presence between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, FrancoAngeli, 1996

- Adriano Donaggio, Venice Biennale: a century of history, Giunti, 1988

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.