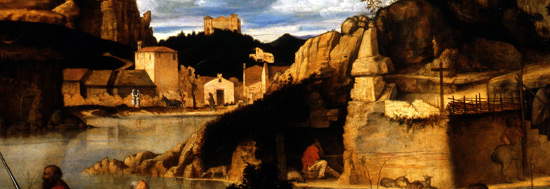

“It is difficult to discover the meaning of the allegory that Bellini painted. The Virgin, seated on a terrace overlooking a lake, receives the homage of a kneeling woman, accompanied to the right and left by standing figures whose identities have not been ascertained. Behind an open balustrade, two men apparently represent St. Joseph and St. Paul. An apple tree in a vase is shaken by a naked boy, and some children pick fruit. In the hills behind the lake, a donkey ruminates and a shepherd tends his flock; we then see a centaur and a hermit resting in a cave. The perfect composition of the scene is really pleasing, as is the purity and choice of forms, the gracefulness of the movements, and the delicacy of the faces. The colors are gentle, mingling and floating in the sunny midday mist.” With these words, Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle described, in his A history of painting in northern Italy written with Joseph Archer Crowe and published in 1871, one of the most enigmatic paintings in the history of art: theAllegory by Giovanni Bellini (c. 1430 - 1516), now preserved in the Uffizi where it arrived in 1793, following an exchange with the Imperial Gallery in Vienna, strongly advocated by Luigi Lanzi. Cavalcaselle, too, had noticed how little penetrable the subject matter depicted by the Venetian painter was, who, as is well known, not infrequently found himself working for illustrious members of the Venetian patriciate who were in the habit of commissioning works whose meaning could only be guessed at by those who belonged to narrow circles of highly educated lovers of art, letters, history and science.

|

| Giovanni Bellini, Allegoria sacra (variously dated between 1487 and 1504; oil on panel, 73 x 119 cm; Florence, Uffizi |

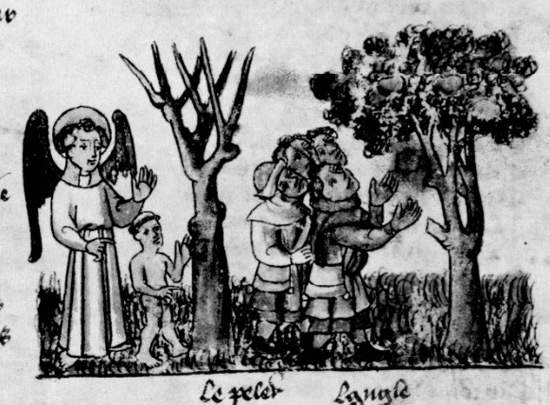

Thus, Cavalcaselle himself, who was moreover the first scholar to attribute the work to Giovanni Bellini (an attribution commonly accepted today), avoided venturing into interpretations. The first art historian to attempt to unravel the difficult puzzle was the German Gustav Ludwig (1852 - 1905): this was 1902, and the attempted explanation called into question an allegorical poem written roughly in the 1450s, entitled Le pèlerinage de l’âme (“The Pilgrimage of the Soul”), by the French monk Guillaume de Deguileville (ca. 1295 - ca. 1380). One of the staples of all interpretations is the presence of sacred figures, so much so that the name by which the painting is perhaps best known is Sacred Allegory: and it is precisely to an allegory of thesoul ’s journey through Hell, Purgatory and Paradise that the painting would refer according to Ludwig’s hypothesis. The terrace would be a representation of the Garden of Eden, a place where souls are gathered while awaiting the judgment that should ascend them to Paradise. The souls would be represented by the children playing around the tree: indeed, in the poem there is reference to one lush tree and another dry tree, and we can see dry shrubs on the shore of the lake. The soul protagonist of the journey would be symbolized by the child sitting on the pillow, clothed: he is in that position as he is awaiting judgment from Our Lady, the saints, and the allegory of justice, represented by the crowned woman standing to the left of the Virgin. The two saints we see standing on the right are identified by Ludwig as Saints Bartholomew and Dionysius, who serve as patrons of the soul at the heavenly tribunal. On the outside of the terrace, the landscape would allude precisely to the journey made by the soul to get to heaven: a journey during which virtues such as patience (the donkey), humility (the flock of sheep) and abstinence (the goat) were necessary in order to shun vice (the centaur), guilty of tempting the hermit. To support his thesis, Ludwig also called into question some miniatures taken from ancient French manuscripts, in which we find depictions similar to those used by Giovanni Bellini: we propose two, one taken from manuscript 1138 in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, which contains a redaction of Deguileville’s poem, and which illustrates the souls playing around the tree, and another, with theallegory of justice, taken from a further illuminated manuscript of the poem, also preserved at the BNF (number 377).

|

| Detail of the children in the center of the scene |

|

| Souls playing around the mystic tree, from Le pèlerinage de l’âme by Guillaume de Deligueville (15th century; Manuscript Bib. Nat. F. fr. No. 1138 Fol. 168 recto) |

|

| Women on the left |

|

| Allegory of Justice, from Le pèlerinage de l’â me by Guillaume de Deligueville (15th century; Manuscript Bib. Nat. F. fr. N. 377 Fol. 148 verso) |

The interpretation provided by Ludwig remained for quite some time the one considered most credible. However, to examine the contradictions of the German scholar’s proposal thought, in 1946, Nicolò Rasmo (1909 - 1986), who meanwhile pointed out that Le pèlerinage de l’âme had never been published in Italy: to the art historian from Trentino it therefore seemed unlikely that Bellini (or his patron) knew it so thoroughly. But the major distortion of Ludwig’s explanation lay, according to Rasmo, in the fact that the German scholar admitted for the seated child a dual role: that of the soul awaiting judgment, but also that of a symbol of Jesus Christ. Ludwig in fact explained the standing figure next to the Madonna by alluding to a passage in the fourteenth-century poem in which the Virgin asks Justice to alter the fate of Jesus, who was supposed to suffer the pains of the Passion. However, unable to interfere in the divine plans, she would have given herself up to weeping, consoled by a pious woman: for Ludwing, she would be the very figure we see in the painting next to the Madonna, standing. According to Rasmo, the hypothesis of a dual role is to be categorically ruled out as implausible. There would be many other inconsistencies with the poem (for example, the fact that the luxuriant tree, in the literary work, grew in the soil of the Garden of Eden, and not inside a vase, and the fact that the Garden itself in the painting is depicted as a terrace instead of a real garden), which would therefore suggest that the allegory represents nothing more than a Holy Conversation. In short, a simple Holy Family with saints (Saint Joseph would be the figure next to Saint Paul) but, according to Rasmo, entirely new and original in its setting and perspective depiction.

|

| The saints identified as St. Joseph and St. Paul |

Following the strictly chronological order in which the interpretations followed one another, we come to 1953, when Frenchman Philippe Verdier (1912 - 1993) rejected Rasmo’s overly simplistic proposal and returned to embrace the idea of allegorical significance. Verdier was convinced that the proposal to see in the women next to the Virgin unidentifiable saints was just a way to avoid solving the problem: those figures had to have meaning. On the fact that the terrace represented Heaven on Earth, Verdier agreed with Ludwig, and the fact that there was only one tree, and in a vase to boot, was to be read as a simplification. Verdier also agreed with Ludwig about the author who would inspire the painting: again Guillaume de Deguileville, with another work, however, namely Le pèlerinage de Jésus-Christ (“The Pilgrimage of Jesus Christ”), from 1358, a poem that takes the form of a kind of commentary on Psalm 84. Exactly like theAnnunciation, a work by a 15th-century Florentine playwright, Feo Belcari, who specialized in religious dramas: for Verdier, Belcari’s play constituted another possible source for Giovanni Bellini. In both Deguileville’s poem and Belcari’s drama we learn about the four figures known as the four “daughters of God”: Justice, Truth, Peace and Mercy. The French monk’s poem describes a contention among the four daughters regarding the redemption of original sin: Peace and Mercy would indeed like to save humanity by redeeming Adam, author of the first sin, while the other two wish for severe punishment (which, according to Justice, should even be eternal). The four therefore turn to Wisdom, who establishes a verdict: humanity will have to be redeemed by the Lord Himself, who will become man and serve the sin for all. Our Lady, according to Verdier’s interpretation, would be a symbol of Wisdom (one of her attributes is in fact Sedes Sapientiae, “Seat of Wisdom”), and the women on either side of her would be the personifications of two of the four opposing virtues, namely Mercy and Justice. The seated child would be Jesus himself, while the figures behind the balustrade would be Simeon the Elder, the elderly man who in Luke’s Gospel foretells to Mary the sufferings of the Passion (appearing in a vision in the form of a sword), and Isaiah, the prophet who had announced the Passion.

A few years later, in 1956, Wolfgang Braunfels (1911 - 1987) preferred to return to anti-allegorical positions by hypothesizing that the painting was a mere representation of the Earthly Paradise: according to the German art historian, no other Christian allegories would have existed in the entire 15th century other than Bellini’s, a detail sufficient to drop the hypothesis of a hidden meaning of the painting, as it was considered not in accordance with the times. That is, it would have been plausible in the thirteenth or fourteenth centuries, but not in a century in which no examples of subjects that were both religious and didactic had been found. And to this it was necessary to add that the “allegorists” had not yet managed to find a reference text that could explain, without contradiction and in a completely fitting way, every single detail of the work.

|

| Giotto, Hope (c. 1305; fresco, 120 x 60 cm; Padua, Scrovegni Chapel) |

|

| Hans Holbein, Tree of Charity (1543; engraving, coat of arms of printer Reynold Wolfe; Washington, Folger Shakespeare Library) |

|

| Detail of the background |

Among the more recent interpretations, it is worth mentioning the one put forward in 1994 by Maurizio Calvesi, who considers the terrace to be a vision of the earthly paradise (of which St. Peter and St. Paul would be the guardians) had by St. Anthony Abbot, which should be identified in the figure of the hermit in the cave, and the very curious hypothesis formulated in 1996 by Werner Hofmann: the Allegory would be nothing more than a whim (albeit dense with symbolic meaning, which would consist in the elimination of barriers between reality and imagination), that is, a fantasy composition in which elements of even the most diverse nature are added. An entirely improbable hypothesis: if so, Giovanni Bellini would have invented a pictorial genre a couple of centuries in advance. Although among the latest commentators prevails the position of those who see in the painting an allegory of redemption (the hypothesis was reiterated by Meinolf Dalhoff in an article that appeared in 2002 in Burlington Magazine), it is still impossible to find a convincing explanation of the painting. No documents exist (or have not yet been discovered) that can help us in this endeavor. On the occasion of the restoration that the work underwent in 2002, Antonio Natali reiterated that when trying to explain complex paintings like this one, the “scientific assumption” requires reference to a source that inspired the artist. It follows that hypotheses are formulated on the basis of the source to which the painting is meant to refer: and everyone could therefore propose a different reading. The conclusion, therefore, can only be one: “Classical culture and theological culture seem here to blend in a humanistic device, which can only be revealed if we succeed in recovering the verisimilarly literary text from which Bellini was inspired when, in the years between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, he painted this work. Unless it happens to be the case, ventilated by some, that every symbolic image in the painting was juxtaposed with the others on an invention due to the artist himself.”

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.