Giotto: the Baroncelli polyptych reunited

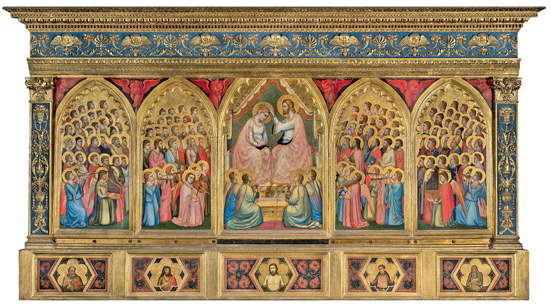

The Milan exhibition on Giotto (1267 - 1337) had, in my opinion, one of its two peaks in the display of the Baroncelli Polyptych reunited for the occasion with the cusp of the central panel (the other peak, however, can be identified in the presence in the exhibition of the Stefaneschi Polyptych, which is leaving the Vatican Museums for the first time). The Baroncelli polyptych and its cusp, normally, would be separated by thousands of miles, since the former is in Florence, in the Basilica of Santa Croce, and the latter is kept at the Museum of Art in San Diego, California. Federico Zeri is credited with recognizing, in the American fragment, the “tip” that anciently completed the central panel of the polyptych. And why it is no longer found together with the rest of the painting is quickly said: in the late 15th century a talented Florentine painter, Sebastiano Mainardi (1460 - 1513), found himself adapting the polyptych to the tastes of the time, according to a practice that was acceptable for those times. So away with the Gothic frame, away with the cusp to place the compartments within a Renaissance rectangular frame, and here appear, in the intervals left by the ogival arches of the compartments, the red seraphim of a clear garlandesque matrix and attributable without too much doubt to Mainardi.

|

| The Baroncelli Polyptych in its usual location: the Baroncelli Chapel in the Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence |

|

| The Baroncelli Polyptych reunited with its cusp in the exhibition Giotto, Italy (Milan, Palazzo Reale, September 2, 2015 - January 10, 2016) |

|

| Giotto and Taddeo Gaddi, The Eternal Father with Angels, cusp of the Baroncelli Polyptych (c. 1328; tempera on panel; 71 x 75 cm; San Diego, The San Diego Museum of Art) |

Let us start with the cusp: how did Federico Zeri come to guess that it was a part of the Baroncelli polyptych? The fragment, the scholar recalls in his essay Due appunti su Giotto (published in 1957 in the journal Paragone), had already been recognized in the 1930s as a work by Giotto by another great art historian of the past, Lionello Venturi, who, however, assigned it to the artist’s Padua period (thus between 1303 and 1309), without recognizing its exact provenance. Zeri, for his part, noticed that the subject and the measurements of the fragment could not suggest that it was the cusp of an isolated panel, and furthermore, as can easily be seen, in the lower part of the painting the top of a triangle can be discerned, which suggested that that figure must be the top of a throne. The throne, Zeri says, is compatible with only two subjects: a Madonna and Child Enthroned, or a Coronation of the Virgin, which would greatly narrow the circle of possible paintings to which the fragment could be referred. If we then turn to examine the central panel of the Baroncelli Polyptych, we can clearly see that the small arches decorating the edges of the compartment coincide with those adorning the edge of the cusp. Also identical is the decorative band that runs around the outside of the small arches, identical is the ornamentation of the corbels of the small arches, and of course the triangle of the cusp matches the throne of the central scene of the Baroncelli Polyptych, where a coronation of the Virgin is depicted, precisely. These are the elements that have led to a recognition now accepted by all critics: one can therefore understand the great opportunity offered by the exhibition Giotto and Italy, which gives a way to see the polyptych and cusp together.

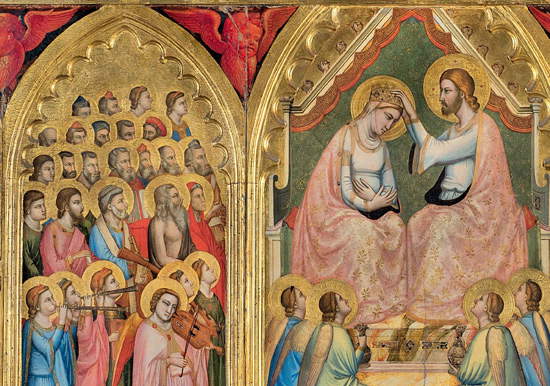

In the center of the latter we see the depiction of God holding the book with the alpha and omega (symbol of the beginning and the end) and holding a sword in his right hand and a branch of thetree of life in his left. Below him flock angels who, to use Federico Zeri’s words, “are heading with lightning, very rapid flight toward that which, in the central and upper part of the figuration, shines with such irresistible radiance as to be unbearable even for beings of pure spirit”: they are therefore forced to shield themselves from the dazzling divine light by making themselves screens with their hands or, very curiously, with smoked glass filters. Zeri, however, referred the execution of the angels not to Giotto but to Taddeo Gaddi (c. 1300 - 1366). In fact, it should be pointed out that the Baroncelli polyptych is a rather problematic painting: there has long been debate about the dating and especially about the extent of Giotto’s interventions on the painting, since there have been those who have referred the painting, in its entirety, to the Tuscan master, and those who have instead assumed more or less extensive help. While the dating debate has settled down, thus finding a temporal collocation for the painting around the date when the Baroncelli chapel was built (thus around 1328), it has been more complicated to identify hands other than Giotto’s in the execution of the work, a work that represents one of the peaks of the artist’s production. In the central panel, as mentioned above, we find a coronation of the Virgin, while on the sides the four panels are entirely occupied by hosts of saints and musician angels ecstatically contemplating the vision before them. We derive from the complex a feeling of profound harmony and great refinement: a complex that happily combines the very modern conception of theunity of the polyptych’s compartments (the five panels in fact participate in the same scene) with the more archaic taste of the saints who, although occupying staggered planes, are arranged in a balanced and almost geometric manner. The saints, moreover, are often individually connoted, and the observer cannot miss the figure with the red headdress who, in the second panel, turns his gaze in the opposite direction from the others: although we have no certainty about this, it could be a figure that Giotto inserted to momentarily break the balance and thus make his painting take on a more markedly earthly connotation. Completing the composition are the tasteful angels who, in playing their instruments, denote a variety and accuracy that would make their assignment to Giotto’s hand almost incontrovertible.

|

| Giotto and Taddeo Gaddi, Baroncelli Polyptych (c. 1328; tempera on panel, 185 x 323 cm; Florence, Basilica of Santa Croce, Baroncelli Chapel) |

|

| Detail of central panel and second compartment |

|

| Detail of the musician angels |

It has been anticipated that the Baroncelli polyptych is a work that has had a rather intense debate around it. Until the nineteenth century it was considered to be a work due exclusively to Giotto: such was the view of the earliest commentators, including Vasari, who told us of “a tempera panel by the hand of Giotto, where the coronation of Our Lady is conducted with much diligence, et un grandissimo numero di figure piccole, et un coro di Angeli e di Santi molto diligentemente lavorati,” and added that “in this work is written in letters of gold his name et il millesimo.” It is in fact one of the few works signed by the Tuscan artist, who in the elegant black hexagons that run along the lower edge of the polyptych, widely spaced from each other, affixed a letter for each figure to form the phrase OPUS MAGISTRI JOCTI, “Work of the master Giotto.” It was precisely on this signature that the first doubts of scholars focused. Adolfo Venturi, in particular, assumed that the inscription was part of the frame designed in the 15th century, paving the way for the reactions of other eminent art historians who immediately followed him in denying Giotto’s authorship of the painting: Venturi, in 1907, formulated the name of Taddeo Gaddi, an attribution that Pietro Toesca called “plausible” in 1927 (not least because he placed it in relation to the frescoes in the Baroncelli chapel, which were painted by Taddeo Gaddi himself) and which was widely accepted by critics of the time. In 1941 Luigi Coletti demonstrated the originality of the signature, while warning that the fact that the signature was 14th-century did not mean that the painting was automatically to be attributed to Giotto. For a clear reassessment of Giotto’s name as the “father” of the painting it was necessary to wait a few years: in particular, Roberto Longhi tended to recognize, especially in the central panel, Giotto’s hand, and on the basis of such considerations several other scholars would later speculate that the painting must have been the result of a collaboration between Giotto and his workshop, or one of his precise pupils (the aforementioned Taddeo Gaddi). It was precisely to a collaboration between Giotto and Taddeo Gaddi that Federico Zeri was thinking: the fact that the polyptych is closely related to the Gaddian frescoes that decorate the chapel in which the painting is preserved, and the modern conception underlying the work, attributable to Giotto’s genius, might indeed suggest such a hypothesis, which is also the one that nowadays finds perhaps the widest favor with critics.

To the knots over the dating and interventions, therefore, a certain and definitive conclusion cannot be affixed, even though certain suppositions have made their way forward that would seem to receive wide support. What is certain is that it is one of the most fascinating works conceived by the master who revolutionized the history of art.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.