At theState Archives in Milan there is a document, dated April 21, 1525, that records the inventory of the property of Gian Giacomo Caprotti known as the Salaì (Oreno, 1480 - Milan, 1524), who was a collaborator and pupil of Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519). This is a document of great importance because it has helped scholars understand what relations there were between the pupil and the master. We know that the Salaì followed Leonardo to France, although he stayed little with him (most likely he was not at the genius’ side when he disappeared): in 1519, Caprotti returned to Milan where, on January 19, 1524, he died a violent and sudden death (he was killed perhaps by an arquebus shot by French soldiers besieging the city, near the house he had built on the land he had inherited from Leonardo, now known as “Leonardo’s vineyard”). The inventory of Salaì’s possessions mentions several paintings, including a Leda and the Swan, a Madonna and Child with St. Anne, a Mona Lisa (mentioned as “quadro dicto la Joconda”: this is the first attestation of the term by which Leonardo’s most famous painting would later become universally known), a Salvator Mundi (“Un Cristo in modo de uno Dio Padre”), a “quadro con una meza nuda,” and a Christ at the Column mentioned as “non fornito,” or unfinished. An estimate is also presented for each of them: the Leda is the painting with the highest value (200 scudi), the Christ at the Column the least valuable (5 scudi).

However, these would not be Leonardo originals, as was thought when the document was found in 1991. In 1999, the French scholar Bertrand Jestaz in fact uncovered an agreement, dating back to 1518, between the Salaì and King Francis I of France from which we get the information that, at that date, Leonardo’s pupil had sold to the French sovereign some paintings (among which was precisely the Mona Lisa) for a sum that corresponded to more than double the works listed in the 1525 inventory. Several hypotheses have been made to identify the paintings mentioned in Salaì’s inventory: for example, the “meza nuda” could be the so-called Mona Vanna, also known as the “Naked Mona Lisa,” a work of uncertain attribution to Gian Giacomo Caprotti now in storage at the Museo Ideale Leonardo in Vinci, which we have discussed more extensively elsewhere on these pages. One of the most singular aspects that nevertheless emerges from the inventory is the inclination that Salaì had toward business. His attitude was diametrically opposed to that of his master: while Leonardo was completely absorbed in his scientific and artistic studies, Salaì looked after his economic interests (in addition, of course, to looking after his own).

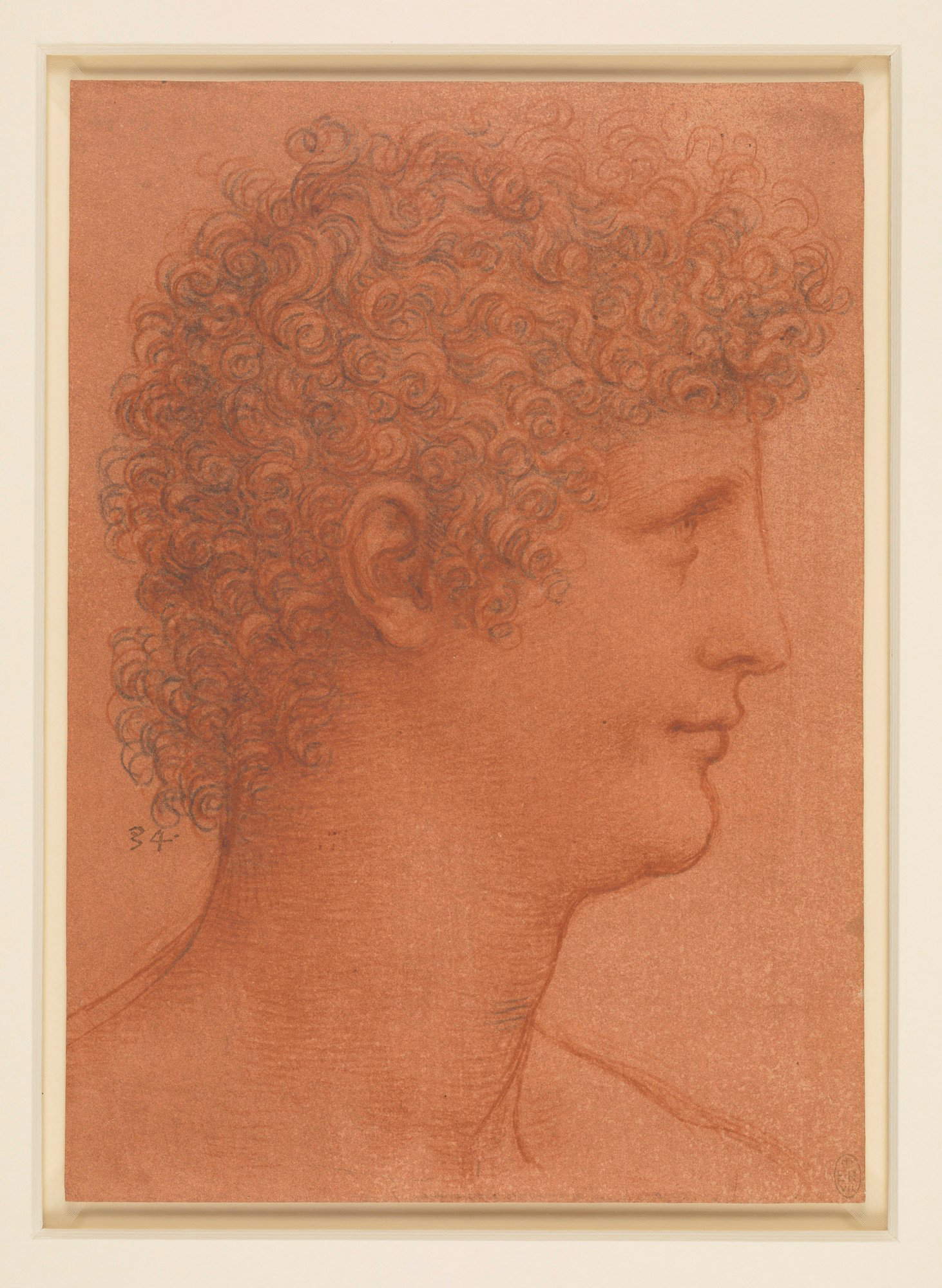

The young Caprotti had entered Leonardo da Vinci’s workshop in Milan as a child, at the age of ten: it is the artist himself who gives us news of Salaì’s entry into his atelier. “Jacomo,” we read on folio 15v of Manuscript C, “came to stay with me on the day of Magdalene in 1490, aged 10 years” (on July 22, 1490). We also know from ancient sources that Salaì was a very handsome young man: Giorgio Vasari, in his Lives, describes him to us as a boy “vaghissimo di grazia e di bellezza, avendo begli capelli ricci ed inanellati, pe’ quali Leonardo si dilettò molto.” In Leonardo da Vinci’s folios (e.g., 12554 or 12557 in the Royal Collection at Windsor) we see a portrait of a young man in profile appear with some frequency, with curly hair, a Greek nose, and slightly effeminate features. The same type also appears in some sheets of the Codex Atlanticus, and it is thought that these may be portraits of Salaì (so much so that similar profiles have been called “Salaì type”).

|

| The inventory of Salaì’s possessions |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Head of Young Man in Profile (c. 1517-1518; black chalk, 193 x 149 mm; Windsor, Royal Collection, inv. RCIN 912557) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Head of Young Man in Profile (c. 1510; black and red chalk on orange paper, 217 x 153 mm; Windsor, Royal Collection, inv. RCIN 912554) |

Salaì’s character was also opposite to Leonardo’s: the great artist is said to have described him as “thief, liar, obstinate, greedy” in one of his notes. Yet, despite the differences in temperament and social class (the young Caprotti was from a humble family: his father, Pietro Caprotti, was the tenant of the land that the master would later bequeath to Salaì), despite the fact that Leonardo’s notes record at least five thefts carried out by Salaì against the master (the nickname, after all, gives a perfect account of his temperament: “Salaì” is in fact the name of a devil in Pulci’s Morgante ), the Tuscan genius kept him with him for almost his entire life. Evidently, the young Caprotti had somehow managed to win Leonardo’s trust, and not just his own. We know, for example, that Salaì, “alevo de Leonardo da Vinci, zovene per la età sua, assai valente,” was commissioned in 1505 by Alvise Ciocca, agent of the marquise of Mantua, Isabella d’Este, to report to the marquise herself on Perugino ’s progress on a painting that the sovereign of Mantua had commissioned from the Umbrian painter: at the time, Isabella had commissioned both Perugino and Leonardo (both of whom were residing in Florence at the time, and Salaì had followed Leonardo to the Tuscan city, just as, for that matter, he had followed him to Venice earlier) to execute two works. And the Salaì, Ciocca wrote, had “lauded much the imagination et ha correcto alquanto alchune cosete ch’el prefato Reverendo [the abbot of Fiesole, ed.] et io havevamo dicto al Perusino.” And Ciocca again informs us that Salaì had expressed a desire to do “some gallant thing” for the marquise: he evidently considered himself such a skilled artist that he was held in esteem by prestigious patrons.

Again, we find Salaì at the master’s side in 1513, along with his other favorite pupil, Francesco Melzi (Milan, 1491 - Vaprio d’Adda, 1570), and two other assistants, such as “Lorenzo” and “Fanfonia,” during the trip to Rome. In 1517, Salaì and Francesco Melzi were the only two of Leonardo’s pupils to follow him to France: probably, however, the only one of the two to remain at his side until the end would have been Francesco Melzi. Salaì is officially recorded as Leonardo’s servant, and he received for his services a hefty salary of one hundred gold scudi in the years 1517-1518: however, documents are silent on his account at the time the artist disappeared on May 2, 1519. What we do know for certain is that on May 21 Salaì was in Milan again, and in 1523, on June 14, he married Bianca Coldiroli d’Annono, who brought him a substantial dowry of 1,700 imperial liras.

The two will also be mentioned in Leonardo’s will, and it is interesting to note the way in which the artist refers to his pupils (it will be worth remembering that Melzi, unlike Salaì, was from a noble family, and of a gentle and gallant disposition): “el prefato Testatore dona et concede ad Messer Francesco de Melzo, Gentilomo de Milano, per remuneratione de’ servitii ad epso gratia lui facti per il passato, tutti et ciaschaduno li libri che el dicto Testatore ha de presente, et altri Instrumenti et Portracti circa l’arte sua et industria de Pictori.” Later, Melzi is also named by Leonardo as the sole executor of his will. As for Salaì instead, “Item epso Testatore dona et concede a sempre mai perpetuamente a Battista de Vilanis suo servitore la metà zoè medietà de uno iardino che ha fora a le mura de Milano, et l’altra metà de epso iardino ad Salay suo servitore nel quale iardino il prefato Salay ha edificata et constructa una casa, la qual sarà e resterà similmente a sempremai perpetudine al dicto Salai, soi heredi, et successori, et ciò in remuneratione di boni et grati servitii, che dicti de Vilanis et Salay suoi servitori hanno facto de qui innanzi”. Melzi, in essence, stands to be heir to all of the artist’s movable property, while Salaì, defined as a “servant” on a par with his trusted assistant Giovan Battista Villani, inherits along with the latter half of the “garden,” but on his half Caprotti had already built a house, where he will live following his return from France. The fact that Melzi and Salaì remained so close to Leonardo for so long, lived for several years together with the master (Melzi was his cohabitant for a long time), and received the largest share of his inheritance, has led some to imagine relationships between master and pupils capable of going far beyond merely professional ones, speculating that between Leonardo and Melzi and between Leonardo and Salaì there were also homoerotic love relationships. Of course, however, we cannot be certain about such suppositions.

|

| Leonardo da Vinci’s so-called vineyard in a photograph published by Pietro Beltrami in 1920 |

What was the artistic stature of Salaì? It should be premised that the reconstruction of his biography is a very recent affair: more in-depth studies on Gian Giacomo Caprotti began only from 1991, when scholar Janice Shell discovered the inventory mentioned at the opening of this article. Until the early twentieth century, the artist was even confused with a nonexistent “Andrea Salaino” who is mentioned in some ancient sources, and who also appears on the monument to Leonardo da Vinci in Milan’s Piazza della Scala, among the genius’ pupils (the others are Cesare da Sesto, Marco d’Oggiono and Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio: the fourth, the Salaì, is precisely mentioned as “Andrea Salaino”). Art historian Romano Nanni, however, does not even consider him an artist in the strict sense: he calls him a “strenuous copyist rather than an original author.” Indeed, of Leonardo’s best-known pupils, Salaì was the only one who did not launch an independent career, and his poor artistic skills are also, in all likelihood, the reason why his figure was long forgotten.

The only work that bears Salaì’s name was recently discovered (although it had already been known to scholars at least since the early twentieth century, and Wilhelm Suida had already attributed it to Gian Giacomo Caprotti in the 1920s): it is a Christ the Redeemer purchased in 2007, in a Sotheby’s auction (at $656,000 against an initial estimate of $450,000), by Bernardo Caprotti (thus, curiously, a namesake of the painter), patron of Esselunga. In 2012, the entrepreneur donated the painting to the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan(later also provoking a quarrel), which subjected it, as is often the case with bequests or donations, to diagnostic investigations, thanks to which the artist’s signature was found (“Fe Salai 1511 Dino,” meaning “Salaì painted the work on a November day in 1511”). However, antiquarian Maurizio Zecchini, who was commissioned by Bernardo Caprotti to purchase the painting on his behalf, believes that the word “Salai” that can be read in the painting is not actually the artist’s signature, but is simply an indication of the subject depicted: Zecchini even went so far as to imagine that the work might be a painting by Leonardo, who wanted to portray his pupil in the shoes of Christ. This hypothesis was immediately discarded by Leonardo scholars (starting with Pietro Marani, who rightly pointed out that the quality of the work is very different from that of the master’s paintings), so much so that the Ambrosiana, in presenting the painting, rather espouses the attribution to the hand of Salaì.

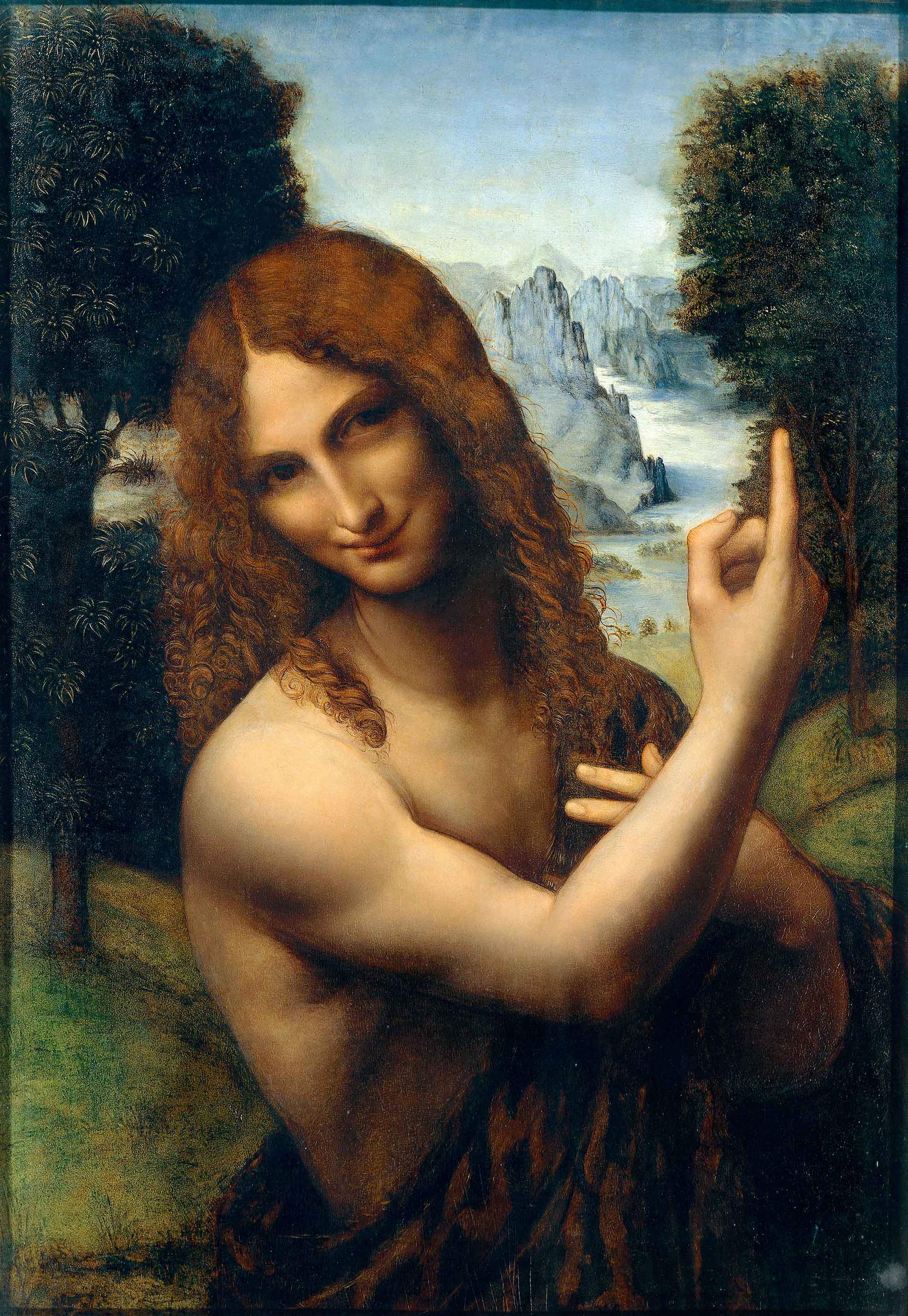

In short, even in the presence of a signature it is difficult to reconstruct Salaì’s artistic activity with certainty, which is why the works that can be approached to his name are only attributed, moreover with numerous discordant voices within the scientific community. The best-known work among those attributed to Gian Giacomo Caprotti is a Saint John the Baptist in the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan, on whose autography, however, critics are far from unanimous, so much so that, even recently, scholarly orientations are moving toward a generic Leonardo painter of the early fifteenth century, although the museum still presents it with the traditional attribution to Salaì. Looking at the painting, Nanni’s judgment is well understood: it is, in fact, a work clearly derived from Leonardo da Vinci’s Saint John the Baptist preserved in the Louvre, albeit with some differences (the most obvious being the landscape above which the author painted the saint). There are also those who have speculated that the Salaì served as a model for the Leonardian Baptist, and that therefore his features are to be found both in the master’s work and in the derived one: the descriptions inferred from the sources have led some to imagine that behind the androgyny of certain Leonardian faces lies the appearance of the Salaì. However, we do not know Salaì’s real appearance because no safe portraits of him survive, so it is highly unlikely, at least at present, to think of finding his portrait in Leonardo’s paintings.

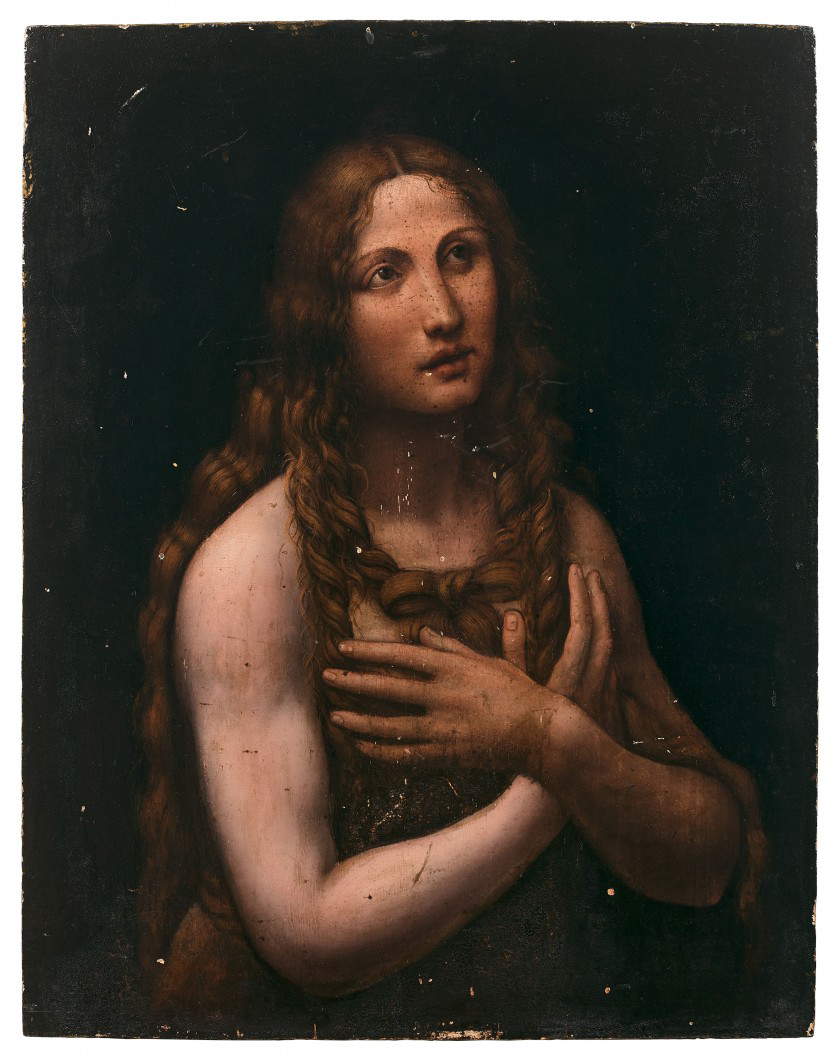

Two other paintings that are usually attributed to Salaì are the so-called Naked Mona Lisa, the work in the Museo Ideale Leonardo da Vinci mentioned above (but even in this case the association between the painting and the name of Leonardo’s pupil is only presumed) and a copy of Leonardo da Vinci’s Madonna and Child with St. Anne, once in the church of Santa Maria presso San Celso in Milan, and now owned by the University of California. Even in this case, however, there is no certainty. There is, finally, one last painting, which has caused much discussion in 2019 because it was sold at auction, at the Artcurial house, for the high figure of $1,745,000: it is a Penitent Magdalene in which the auction house’s experts wanted to see the hand of Salaì on the basis of the comparison with the Christ the Redeemer in the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, “the only work of certain attribution of Leonardo’s favorite pupil,” read the file on the painting drafted by Cristina Geddo. “The Penitent Magdalene,” the text further reads, “presents all the characteristics of the Christ of the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana: above all, an obsessive attention to detail, rendered with surprising mastery, close to that of Leonardo. Similarities can be found in the warm tones used for the complexions, the meticulous calligraphy, the eyebrows, and especially the eyes, emphasized in their lower part by a luminous accent of white or pale pink paint. Last but not least, the intense, charismatic gaze in the Ambrosian Christ, which is meant to be seen almost as a signature of the painter.” On this basis, Geddo also retroactively attributed to Salaì another Magdalene, which went to auction at Dorotheum on April 9, 2014, believed by the scholar to be even “closer to the Ambrosiana Christ” (the Artcurial Magdalene would instead be a more mature work). The Viennese auction house, in 2014, referred the work to a “follower of Leonardo da Vinci,” pointing to it as exemplified on a model of the Giampietrino (Giovanni Pietro Rizzoli; Milan, c. 1490 - 1533) of c. 1525, kept in a private collection. In essence, the question of Salaì’s artistic production remains extremely complex and convoluted to this day.

|

| Gian Giacomo Caprotti known as the Salaì, Head of Christ the Redeemer (1511; oil on panel, 57.5 x 37.5 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana) |

|

| Gian Giacomo Caprotti known as Salaì (?), Saint John the Baptist (c. 1520; tempera and oil on panel, 73 x 50.9 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana) |

|

| Gian Giacomo Caprotti known as the Salaì (?), Mona Lisa nude (1515-1525?; oil on panel transported on canvas; Private collection, on deposit in Vinci, Museo Ideale Leonardo da Vinci) |

|

| Gian Giacomo Caprotti known as the Salaì (?), Madonna and Child with Saint Anne (c. 1520; oil on panel, 177.8 x 114.3 cm; Los Angeles, University of California, Wight Art Gallery) |

|

| Gian Giacomo Caprotti known as the Salaì (?), Penitent Magdalene (c. 1515-1520; oil on panel, 65 x 51 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Follower of Leonardo da Vinci, Penitent Magdalene (c. 1525?; oil on panel, 74 x 53 cm; Private collection) |

Salaì was thus, rather than a particularly talented pupil, a “friend and helper” (as Janice Shell calls him) of Leonardo da Vinci. A helper, certainly, very interested: from the master’s own annotations we can get the idea of an apprentice with whom the master was extremely generous, so much so that thanks to the many years in which he was close to him (and Leonardo was prodigal with conspicuous donations to Caprotti: he even lent him the money for his sister’s wedding dowry), Salaì was able to get rich and become one of the trusted men of one of the most celebrated figures of his time. Not bad for that young, “reckless pupil” affected by “a certain mental disorder,” as one of Leonardo’s leading scholars, Carlo Pedretti, had to write about him. And his biographical story, in addition to his friendship with the master and his rivalry with Francesco Melzi, are among the elements that most contribute to the fascination surrounding the figure of Salaì. So much so that even Pietro Marani, in 2011, shedding his scholarly shoes for a moment, decided to dedicate his debut novel, The Pink Stockings of Salaì, precisely to the antagonism between Melzi and Salaì. On the one hand the “devoted and noble disciple,” on the other the “reckless pupil” with emphasized, right from the title, the propensity of the master to spend large sums to dress Gian Giacomo in luxurious clothes. A story perhaps not as well known as others, but one that continues to fascinate audiences and scholars alike.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.