Giambattista Tiepolo's Apotheosis of the Pisans, the masterpiece of eighteenth-century fiction

Nestled along the banks of the Naviglio del Brenta canal, just a short walk from the center of the town of Stra, stands the “queen of the villas of the Veneto,” Villa Pisani, a majestic example of an 18th-century patrician residence, erected beginning in 1721 by the Pisani di Santo Stefano, a branch of one of the most powerful Venetian families of the time who wanted to establish a grand holiday residence here: we owe to Gerolamo Frigimelica and Francesco Maria Preti the design of the neo-Palladian villa, completed in 1756, and so sumptuous that it was purchased by Napoleon Bonaparte when, in the early 19th century, the Pisani, overburdened with debt, decided to put it up for sale. It was then the representative seat of the Lombardo-Veneto kingdom and, after the unification of Italy, became a museum, although it experienced a period of neglect in the early twentieth century. The visit begins by threading through the most beautiful of the one hundred rooms on the piano nobile (originally 114, in homage to Alvise Pisani who was Doge number 114 of the Serenissima, later to become more than one hundred and sixty with subsequent remodeling), and concludes in the most valuable room, the great Ballroom, whose ceiling is frescoed with one of the greatest masterpieces of airy, luminous 18th-century painting: theApotheosis of the Pisani Family, the pinnacle of painting by Giambattista Tiepolo (Venice, 1696 - Madrid, 1770).

For Tiepolo, the commission to decorate the largest room in the Villa Pisani, in a space more than twelve by seven meters, represented his last venture in Italy before his final move to Spain: the work dates back to 1761-1762, when the great Venetian artist had just returned from some extraordinary successful works (such as the decoration of Villa Valmarana in Vicenza in 1757 and even earlier, in 1753, the decoration of the Residence of the Prince-Bishop of Würzburg in Germany) that had made him one of the most sought-after painters of his time. His ability to paint large frescoed vaults according to the prevailing taste of the time, with dreamlike representations far removed from reality, vast and luminous skies, colors in muted, unrealistic and almost abstract tones, a spatiality deliberately fictitious, had evidently convinced Almorò (or Ermolao) III Alvise Pisani (son of the Alvise Pisani who, together with his brother Almorò, had commissioned the villa in Frigimelica) to assign him, in 1760, the task of decorating the ballroom. In May of that year, Tiepolo presented the family with a model, now housed at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Angers, France, to which the painter would later faithfully adhere, except for a few minor variations, in restoring the composition on the vault.

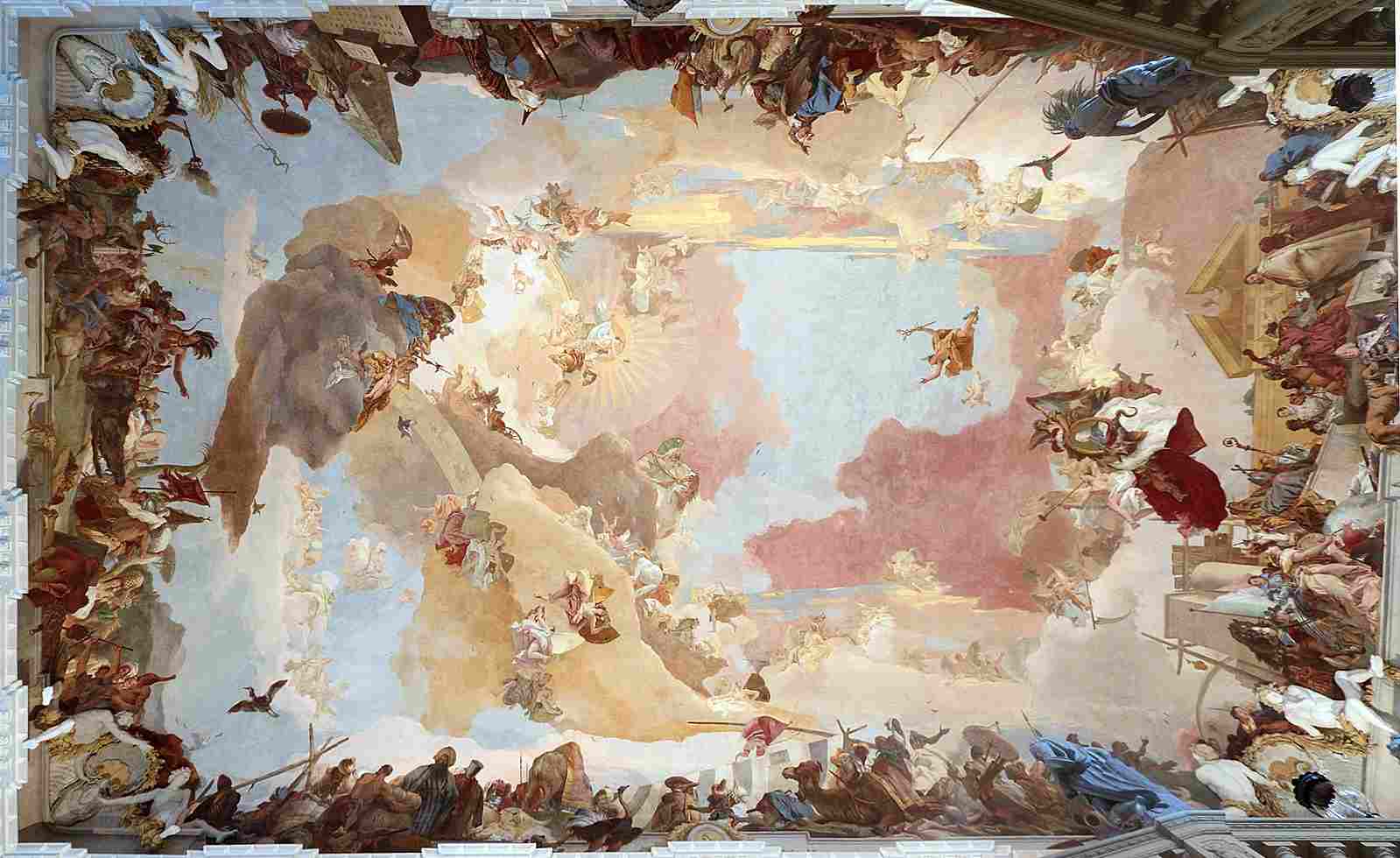

The theme is, as anticipated, the glorification of the family, of the Pisani, protagonists for at least four centuries of the political events of the Serenissima: a traditional iconographic subject, since many noble families, for the decorative cycles of their residences, opted for scenes depicting the apotheosis of some ancestor, or the exploits in which their ancestors had participated. The unusual choice consists in the fact that in this fresco the Pisans did not choose to include the figures of ancestors, but had Tiepolo portray several living members of the family. The blue sky, furrowed, however, by broad white clouds, which occupies all the space enclosed in a mixtilinear frame designed by a specialist, the Milanese architect Pietro Visconti, is nevertheless the real protagonist of the fresco, occupying about two-thirds of the pictorial surface: the main characters occupy the lower and upper registers instead. As a result, there are also no quadratures, that is, fake illusionistic architectures, as was the case inBaroque art: in Tiepole’s fiction, the characters are freely arranged in the sky, without being part of any illusionism other than that of an infinite space, without the idea of wanting to be believable, as was the case in the art of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Only one element is entrusted with the task of balancing the scene: light, which together with the sky we can consider the co-protagonist of the painting, and which with different variations in intensity, tone, and effects that sometimes verge on transparency and sometimes create gloomy shadows, almost ends up merging the figures into the great celestial expanse that the visitor to Villa Pisani in Stra finds before his eyes if he looks up inside the ballroom. As a result, lacking an architectural structure and freely arranging the figures within the space, the regularity of the narrative, which is much looser and more independent than the sequences of the Baroque frescoes, is also lost.

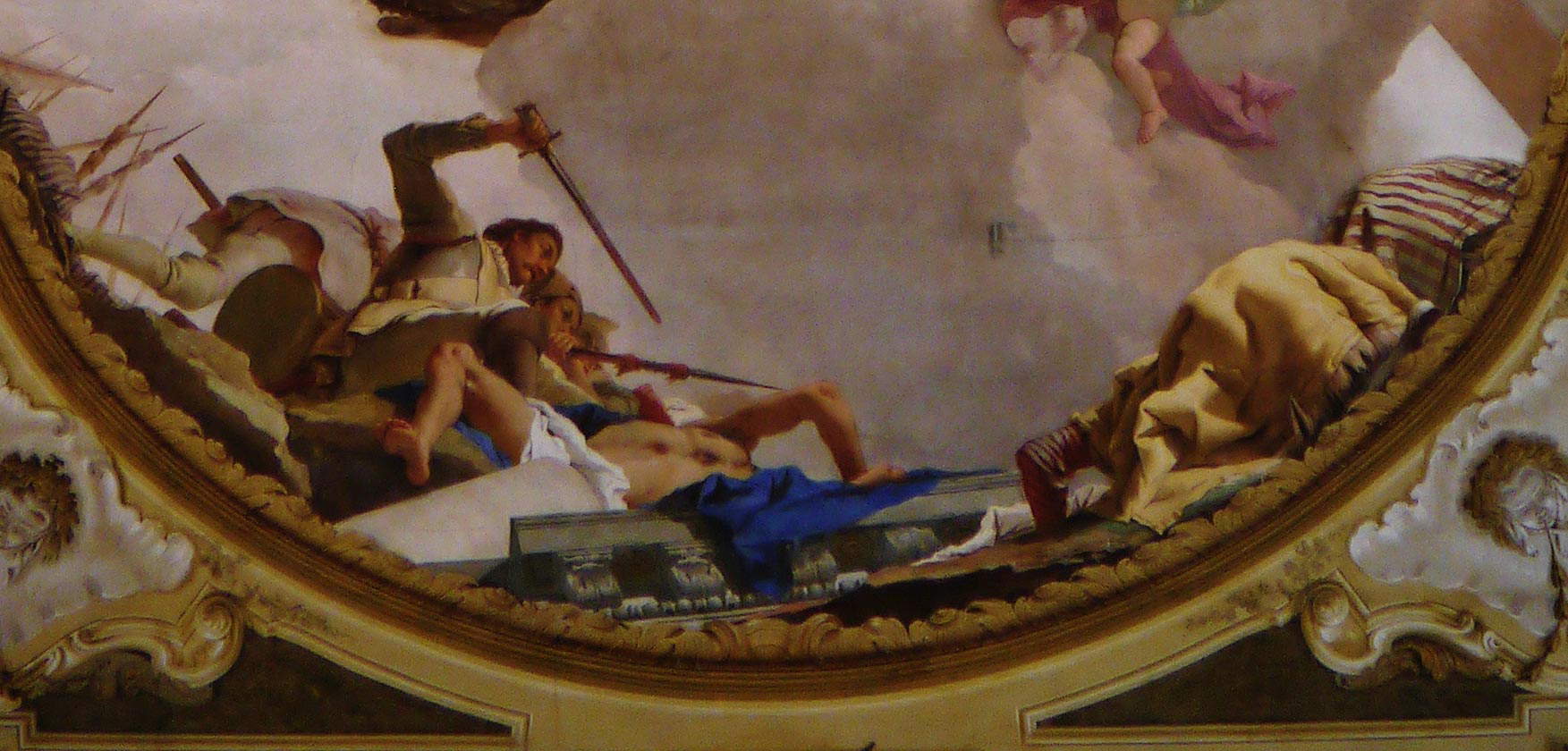

There are several groups of characters that can be distinguished in the fresco: at the lower left we can recognize some members of the Pisani family, while near them, straddling the frame and under the grove that occupies the lower part of the scene, here are some musicians (thus singing the deeds of the family and sanctioning its glory, but they could also allude to the Venetian people enjoying prosperity under Pisani rule), while above an angel playing a trumpet decries the fame of the Pisani. In the center of the fresco, evanescent, diaphanous and almost transparent, we notice the Virgin, blurred in the clouds, caught blessing the family surrounded by a vast theory of female figures, personifications of the virtues of the Pisans. Finally, at the top left, the allegories of the four continents, alluding to the family’s commercial activities, or the lands touched by their fame.

A recent study (2016) by art historian Francesca Marcellan has related the figures of Tiepolo’s fresco to the statues sculpted by Francesco Bertos (Dolo, 1768 - 1741) for the crowning of the two facades of the Villa Pisani, the one facing the Brenta and the one facing the villa’s large park instead: indeed, the fresco would be a synthesis of the rich iconographic program of the villa’s exterior, aimed at making the aristocracy appear as the best of possible governments. “To do this,” Marcellan explains, “numerous allegories are taken up, but the parataxis of the facades, marked in a ternary rhythm dictated by the tympani, is replaced in the fresco by a syntax that proceeds by compact groups of figures. Exactly as in the facades, however, the southern part of the composition develops the theme of good government, while the northern part is reserved for the war theme.” Taking charge of this program, then, are the allegorical figures arranged throughout the fresco: Our Lady finds herself surrounded by the theological and cardinal virtues, considered indispensable for good government. Thus, at her feet are Faith (veiled, as she holds the sacred text), Justice (facing her and holding the scales), Charity (the one holding the child in her hands), Hope (with one of her attributes, the anchor), and finally Fortitude, hidden in the background behind a cloud (we see only her head). Further down is the depiction of turreted Italy pointing to Peace, a foreshortened figure holding two olive branches in her hands. And since only in times of peace are the arts and sciences possible, here we see below her Painting (holding a small paintbrush in her left hand), Sculpture (holding a marble portrait), Music (further back, almost hidden, with a musical instrument) and Astronomy (with armillary sphere and telescope). On the opposite side, however, we notice Spring, depicted as a naked young woman with butterfly wings, whose head is crowned with flowers and who holds in her hands a garland and a vase decorated with a lion’s head. Below the Primavera, a symbol of the abundance and prosperity that characterizes all good government, appear instead the players mentioned above. Next to the Primavera, wearing a rich brocade dress, is the allegory of Venice, who holds on her legs a very young Alvise Almoro Pisani, son of Almorò Alvise III, while at her side appears the figure of Venus, who instead protects Alvise Almoro’s cousin, Almorò II, and who, Marcellan explains, “is justified in the fresco precisely as an alter ego of Venice.” in fact, the idea is that Alvise Pisani’s descendants are entitled to political power, while his brother Almorò’s descendants are entitled to cultural power. According to scholar Adriano Mariuz, to whom one of the most important readings of this fresco is due, the presence of the very young Pisani might allude not only to the glory of the family, but to the promise of a new generation of excellent rulers: a fresco that, therefore, would look to the future.

On the opposite side, on the other hand, one notices the personifications of the four continents. On a cloud, along with a bull and a temple, we see Europe, toward which Italy turns its gaze, implying one of the political meanings of the fresco: the Pisans proposing Venice as mediator between Italy and Europe. The continents have never been identified with certainty (Europe removed because of easily recognizable iconographic attributes). The figure with trunk and large elephant ears has been variously interpreted as either Africa or Asia, although a strange crocodile is seen near her, which was usually an iconographic attribute of America because of the presence of alligators. America, on the other hand, is personified by the two figures with feathered headdresses, one equipped with a quiver with arrows, the other with a cornucopia. However, if America were to be identified with both figures, Asia would be missing: according to the most traditional reading, that of Filippo Pedrocco, it would be the figure with the attributes of the elephant, so that the figure with cornucopia becomes an allegory of Africa, and the one with the quiver would be America. Also according to Adriano Mariuz, Asia is identifiable with the elephant-eared woman, and for one more reason: she is the only one who does not turn to fame, and the scholar explains this gesture by the fact that at the time the Turks, Venice’s enemies, ruled in Asia, thus adding another political motivation. Marcellan, on the other hand, supports the thesis of the pair of figures with the feathered headdress as allegories of America, while Asia would be identified in the two figures kneeling in front of the soldiers appearing on the opposite side and symbolizing the military strength of Venice. “Here in Stra,” according to the scholar, “the gesture identifying Asia is that of submission to Venetian force, bulwark of Christendom thanks to its fleet, whose presence is suggested by metonymy by the ship masts (also present in Würzburg) behind the soldiers.” The same genuflected figures are found, moreover, in the Würzburg frescoes. However, they have also been interpreted by others as allegories of the Turks (because of their clothing) surrendering to Christian forces. The message would thus be reinforced by the naked women who appear more in the center, near a large winged dragon, and who are perhaps symbolic of Discord or Heresy. On the opposite side, some emaciated figures appear next to three sorrowful youths: they could signify the nefarious effects of war and discord. However, there is still no agreement on the reading of this wonderful fresco.

The great vault of the ballroom of the Villa Pisani imposed itself as the last, great glorifying image of a family, the last expression of a civilization that was becoming extinct and that saw in Tiepolo its last, great artist, heir to a tradition that in Venetian lands started at least from the sixteenth century, from when Paolo Veronese frescoed the rooms of Villa Barbaro in Maser, but that had other significant stages along the history of art. It would be Roberto Longhi, in his imaginary dialogue between Caravaggio and Tiepolo, who would go over this story in broad strokes, not without a little irony, imagining that it was Tiepolo himself who told it: “That great Barberini whom you knew monsignor fabricated for himself a room larger than this Campo, where a painter who was Cortona, made swarm from the papal coat of arms bees larger than men. Father Pozzo multiplied in the ceiling the factory of St. Ignatius; the Jesuits’ vault Baciccio spread it; Giordano, that of the Riccardi in Florence. These, the greats of modern painting, brought by the greats of the earth, pontiffs, kings of France and Spain, cardinals, princes and prince-bishops of Austria and Germany. Great things, ’great taste’ (so it is said) of which the nobility and the Church held the scepter without any thought other than to glorify themselves in the vault of their own halls, supposedly a foretaste of the vault of heaven. A dense network of emblems and allegories, where bizarreness and acuteness hold the place of invention; while, after framing the coats of arms of exploits never accomplished, of genealogies often presumptive, the ’histories’ are extracted. Of such greats, I, perhaps, will have been the last. Do you want some titles of my most famous works? ’Allegory of Magnanimity,’ ’Allegory of Nobility and Virtue,’ ’Allegory of Nobility and Courage’; all sentiments to be exchanged only between great personages; or historical facts, insignificant perhaps, but redolent to greater luster of great families: ’The Reception of Henry III , King of France’ by the Contarini, at the Mira (what an honor for the lineage!); ’Apollo leading his bride Beatrice of Burgundy’ in the salon of the Greiffenklau in Würzburg; the Glories of the House of Pisani; or, if there was really nothing to it, Roman history made up for it, as was the case with the ’Facts of Antony and Cleopatra for the Labia counts.’”

These, in short, are the illustrious precedents of theApotheosis of the Pisani family, which moreover remains the largest of the frescoes painted by Giambattista Tiepolo in a private residence. And Tiepolo’s fresco at Villa Pisani likewise remains the work that tells of an era in its twilight years. It clashes the Pisani’s illusory confidence in the future with a reality that was anything but rosy: by the time the great Venetian artist finished his masterpiece, the power of Venice was in decline. Having lost its economic prestige, lost its military might, and eroded its cultural supremacy, all that remained was its independence, which, however, was also destined to vanish within thirty years. Tiepolo, who was sixty-four years old when he began the undertaking of the Palazzo Pisani, would be spared the end of the Serenissima, since he disappeared a few years after finishing his masterpiece.

And for a world that was coming to an end but still deluded into thinking it had some hope for the future, Tiepolo’s language, grounded in the illusory nature of its fictions, could not have been more suitable. And it was also among the most innovative proposals to be seen in the Italy of the time: Venice was, yes, a decadent city, but it was still a culturally vibrant city, open to the world, able to attract artists and men of letters, patrons and collectors, merchants and buyers, still able to impose tastes, fashions, trends. In this city so alive, Tiepolo recovered the great tradition of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (perhaps, as Longhi imagined, even having the full knowledge of being its great heir), to create an emphatic language, splendidly rhetorical, based on an unscrupulous use of light, used to give life to the most obvious illusions. Tiepolo, Nicola Spinosa has written, “knew how to invent [...] a world, an imaginary and fictitious reality, an abnormal and immeasurable space that the spectator [...] always perceives as an entity ’other’ from his own physical and psychic universe, outside his concrete natural and existential reality, beyond any limit placed on his pure infinite spatial dimension. With Tiepolo, the Baroque conception of the infinite spatial continuity between dream and reality, art and nature, myth and history seems to have been definitively exhausted in order to return the artist to a condition not unlike that of the manner years; to the bitter consciousness of an impossible identity and now also of an impossible continuity between the world of art and the world of life. And Tiepolo of this impossibility and this diversity lucidly grasps the value and meaning: in fact, differentiating himself from the great masters of the Baroque seventeenth century, he clearly feels that with his painting of grand theatrical effects, of an endless luminosity and spatiality, he goes far beyond the same theatrical, spectacular conception of nature and life that had matured at the beginning of the previous century, to place himself in a totally abstract, unreal dimension.”

Villa Pisani represents perhaps the greatest result of this unhinging from within of the Baroque language of the various Luca Giordano, Andrea Pozzo, and Pietro da Cortona. Tiepolo, in other words, represents “the extreme chapter of the Baroque conception of infinite spatial continuity,” as Carlo Bertelli has written. The civilization that had produced the highest degree of illusion, with the aim, however, of being taken at face value, of enlarging space, is by Tiepolo conducted to the extreme consequences of what his artists had elaborated, to a painting that employs similar means to extend spatiality infinitely and to create a space that no longer wants to deceive the observer, but wants to reveal to him clearly that what he is witnessing is nothing but a fiction, as they say. A fiction among the most magniloquent, among the most absurdly beautiful in the entire history of art, and which in the ballroom of Villa Pisani lives its most intense season.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.