Did Antonio Canova have a “traveling companion” who was such by affection and artistic consonance? The answer must glide to Bologna, the city that gave him as a young man the great teaching of naturalness and empites of life, and which then granted him, by a happy chance, the admiring and variously translating friendship of Giacomo De Maria, sculptor (1760-1838). Let us keep in mind the long phrasing together of the divine Antonio with the friend who, from the capital of Bologna, corresponded to him luminously in plastic forms, and who moreover expanded the canons of perfection through a rooted but scrupulous and sonorous Cispadan language.

Having said this as a parenthesis and prelude, the reader will forgive the writer a kind of mirroring of values on the everlasting efforts of the indefatigable chiselers on stones and marbles that have forged over the centuries the solid and monumental appearance of our civilization: it is a claim to prominence that cannot be missed. Sculpture has always been the art of memory: a concrete, social and choral memory, a legacy of signs, beginning with the most ancient peoples, that we all regard with extreme care and often with emotion. An art of iconic presences destined for perpetuity, also vocated to the link with architecture and therefore monumental, indelible, solemn; capable of being a powerful hymn of power or victory; or a lyrical and melodious offering to the light. We think of the messages of the rocky Mesopotamian figures, of the granite Egyptian giants, or on the other hand of the small Cycladic idols offered to the tenderest caress of the sun, there in the Aegean aurora. Sculpture dialogues through the centuries, signifies events, gives body to gods and heroes, goddesses and heroines, makes nymphs and maidens dance, meditates with saints. All this we say to confirm the assumption of the centrality of sculpture in the history of the arts, even though today painting and all other images, colorful and motile, distract most of the people from a balanced judgment on the visible expressions of our civilization.

The Cispadane lands, impregnated with the fluvial millenary silt, have not been exempt from petrous and marble endeavors in centuries past, but in the Renaissance and subsequent generations they developed what we might call the epic poetry of clay, addressed firstly to religious depictions of immediate spiritual consonance and to the spectacular sacred theaters of the “Mourners,” capable of shaking hearts to the most intimate and convivial grief. And then, with the inducing aid of the plaster quarries - from which come scagliole and stuccoes of proven docility - these same lands became a dense workshop of figurative, corporeal animations, ubiquitous in churches and palaces, for ornaments and semantic suggestions: almost a universe in counterpoint to life and social fabrication.

In this context Giacomo De Maria was born in Bologna-three years after little Antonio di Possagno-to a family not wealthy but linked by service to the Marchesi Zambeccari. The boy’s precocious talent is carefully noted; his schooling proceeds in the usual disciplines (among them French and Latin), and his vocation for figurative modeling soon gains him a notable and paternal teacher in Domenico Piò, a descendant of the famous sculptors, now secretary of the Accademia Clementina. From his years at the Academy, punctuated by prizes, to the Roman sojourn offered him by noble supporters, to his “society” with his master, our artist’s artistic evolution was clearly affirmed in Bologna and obtained him the title of Accademico Clementino running the year 1789.

In the advanced eighteenth century, the panorama of sculptors in the city does not include relevant names, and yet the manifestations of plastic art are numerous in the unfailing decorations: in the “machines” that impressed people on calendrical occasions or those of great families, in spectacular processions, in carnivals where everything, in the condition of the ephemeral, was colorful and imaginative. This world of angels, of festoons, of flying cherubs, of ecstatic religious, of mythological or allegorical protagonists, was provided for by those numerous minor characters of plasticators, molders, plasterers, to whom Eugenio Riccòmini has devoted excellent studies, and where shone until almost 1770 (the year of his departure) Angelo Gabriello Piò, father of Domenico, a modeler of high grace and remarkable taste who worked in that “Emilian rococo” of stucco and painted papier-mâché that can still enchant for its vexatiousness and lightness but was now outmoded by time and the new courtly severity of neoclassicism.

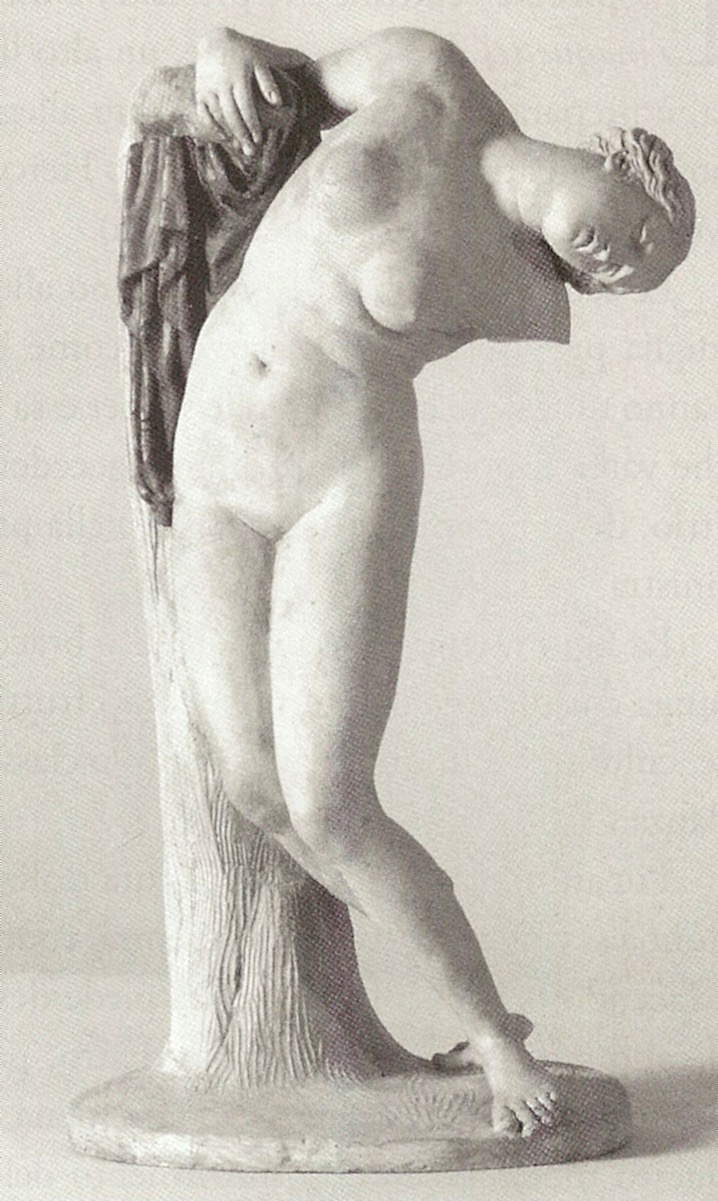

In the Urbe, a city from which he would never depart, Giacomo De Maria immersed himself in the grandiose universe of ancient sculpture and in exciting comparisons with the brilliant protagonists of the Roman Renaissance and seventeenth century; in particular he was able to experience the complex world of the marmorari workshops and their effective organization on the blocks and on the use of the many tools that passed from the forges to the hands of the workers, divided into successive categories: from pointers to subbiatori, from gradinatori to finitori, to the most expert raspers. All under the eye and hand of the Master who ultimately completed each part and then guided the polishers, used the mordants and finally the waxes. And here his personal rapprochement with Antonio Canova, first as an admiring visitor to the workshop on Via delle Colonnette, and then welcomed into a genuine friendship that remained nurtured and reciprocated forever, contributes decisively.

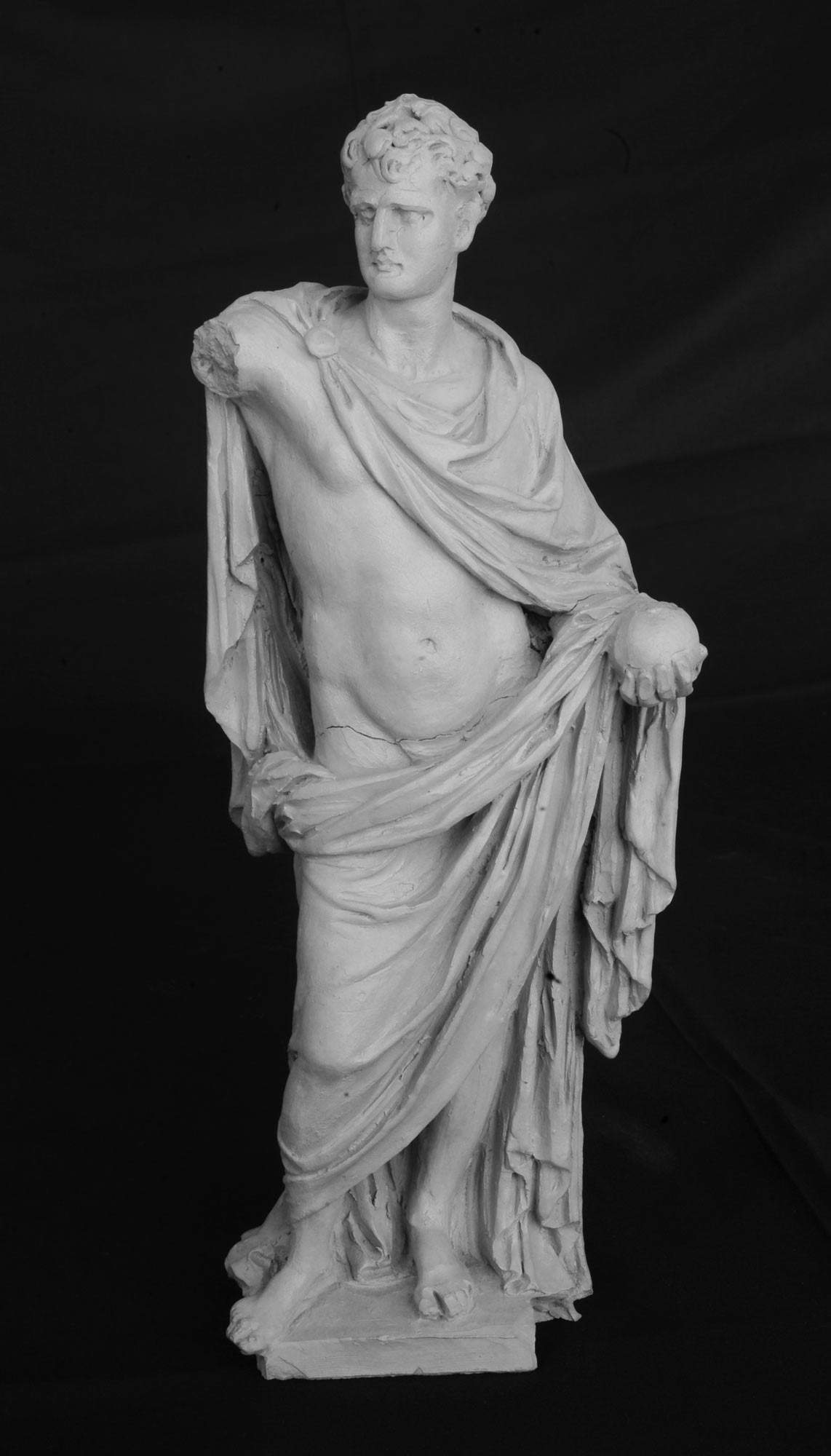

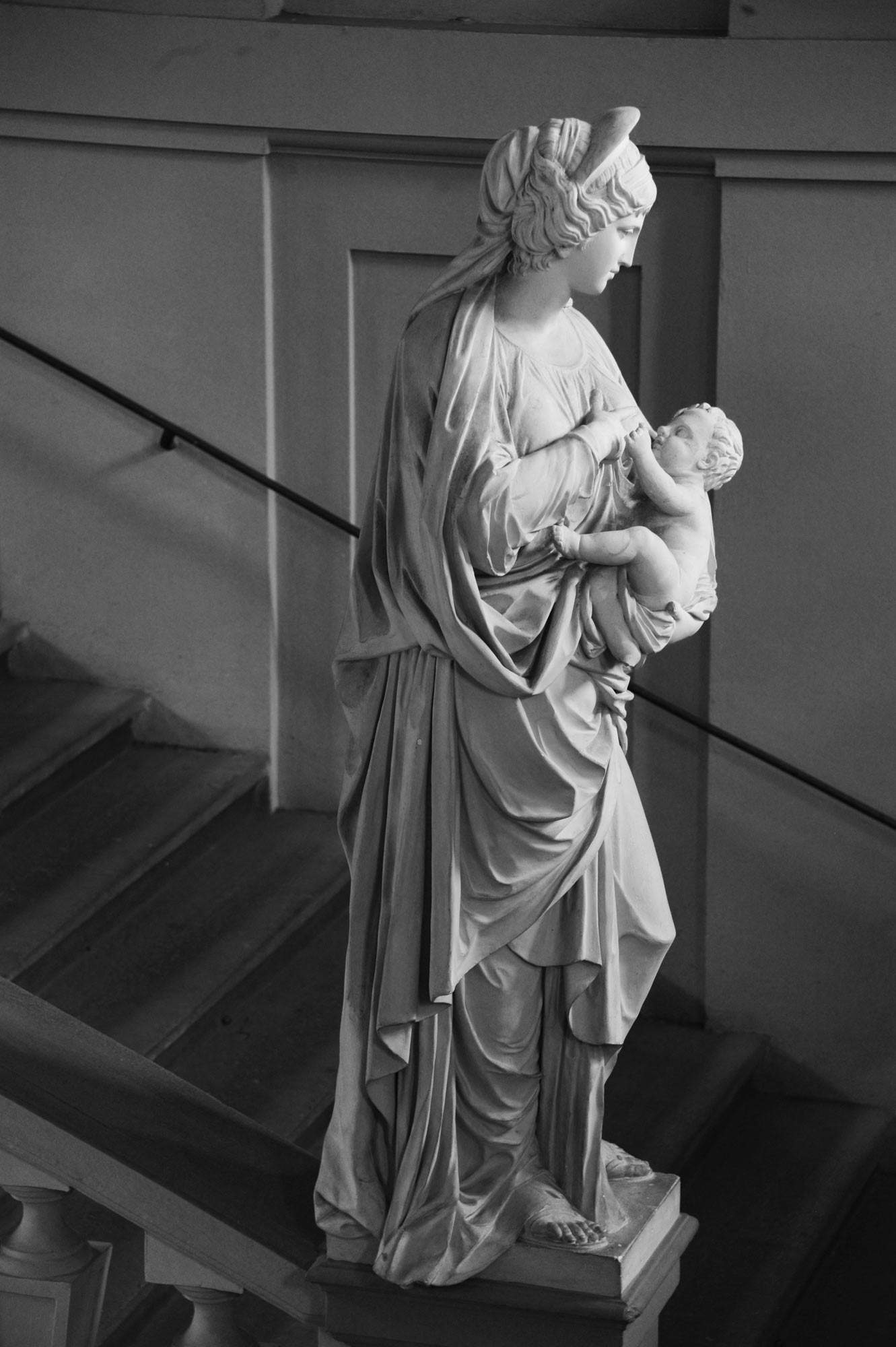

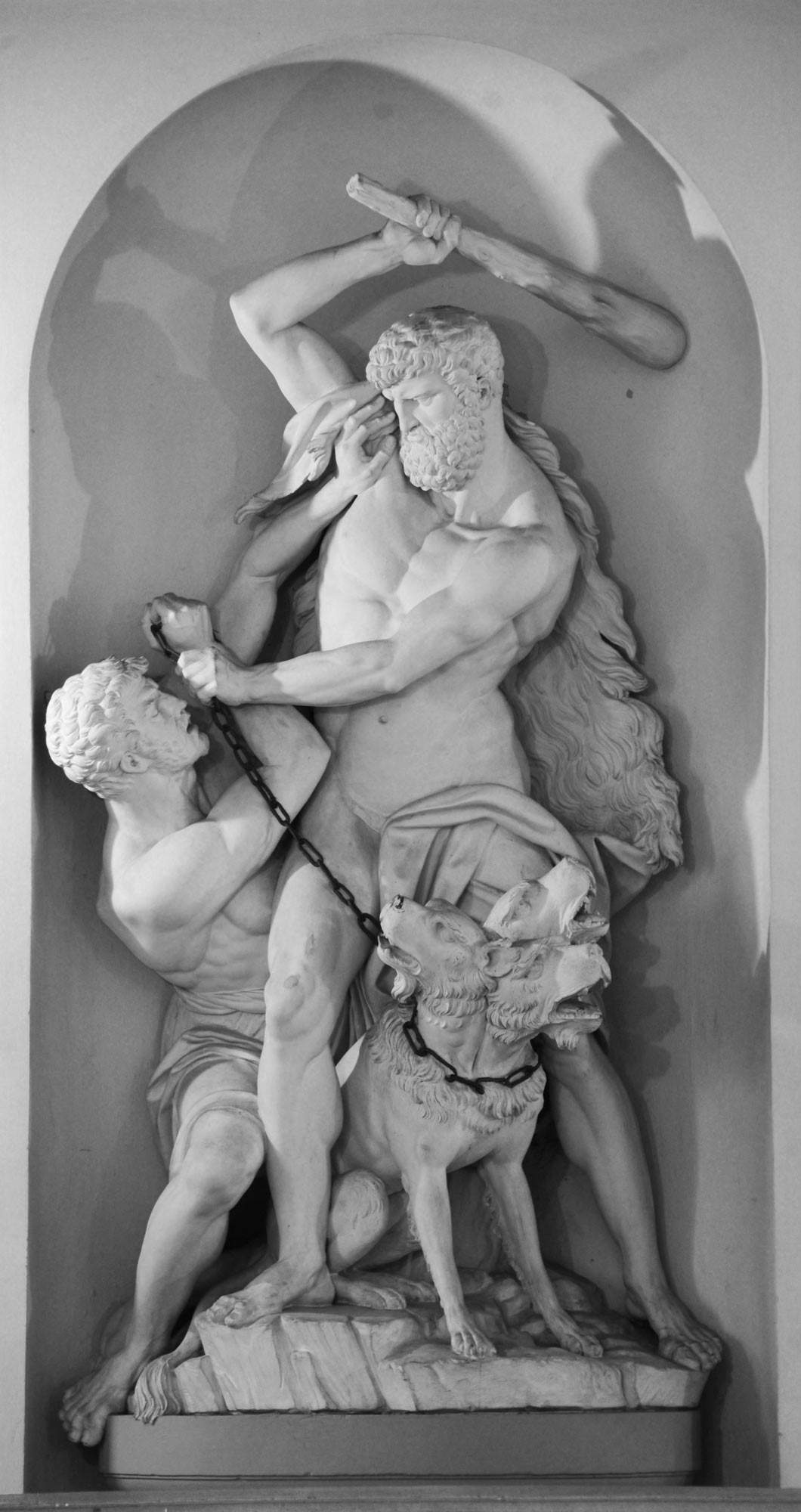

All this is to understand how De Maria, having returned to Bologna and having been honored with tenure at the Academy of Fine Arts, was able to translate sculpture from stucco to marble. In fact, the translation was a historically substantial act: from the albeit sincere images of his predecessors to the epic force of neoclassicism, which he understood in essence and language. We have mentioned a datum of enrichment that the new master brings to Canova’s admirable and delicate balance, and this is the quantum that could not but be there for the autonomous and precise personality of De Maria, who was an animated artist, endowed with specific character and broad Emilian loquacity. One only has to look at his groups to immediately understand their dilated, articulate and profound gènesi.

Here we are finally rescued by Antonella Mampieri’s monumental monograph, made through a great many studies. The adjective is most appropriate, since the two volumes published by Pàtron, in their first edition in September 2020, although of normal size are an absolute cornerstone of art criticism: particularly for the multi-articulated era of the transition between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and precisely for that fundamental art, not easy to explore, which is sculpture. After the Covid interlude, which clouded everything, here is the time to give luster to an exceptional instrument of knowledge and documentation as this monograph is. The systematic order of the two volumes, the many years of research and visitation of every work and every document, the meticulous justification of every passage and every comparison, render a victorious honor to Antonella Mampieri who confirms herself as the first expert-already well known-of Bolognese artistic life after theancien régime. Indeed, the author’s prospecting is not limited to the albeit arduous search for every piece and every limb of De Maria’s works, but reconnects each passage to the general climate of the arts, to the cultural and civic events of the Bologna of the time, and to those subtle vibrations that denote the preconii of Romanticism and thence, of the national resurgence.

For many, the authentic personality of Giacomo De Maria will be a rediscovery, but the highly cultured and delightful narrative with which the author composes the first volume - in eight stimulating chapters plus the Regesto - may constitute an extraordinary artistic-cultural supply and an enrichment that can no longer be forgotten. The second volume is devoted to the 182 entries of the works, where Mampieri’s exhaustive drafting not only gets to the extreme information but becomes a prènsile and colloquial accompaniment that pours out the pleasure of knowledge. The apparatuses follow.

With simplicity we can point to this work as the highest recognition to a great sculptor, and as a civic merit, in Bologna, for a scholar of indispensable magisterium. Let us close with a reminder again of the great bond to which we have alluded and of the imaginary but real role of “traveling companion” for our artist. In September 1822, a month before his death, Antonio Canova came to Bologna for the last time: here he wanted to stop for a long time, in the Certosa Cemetery, gazing, moved, at the veiled statue of the monument to Carlo Caprara, the work of his beloved friend Giacomo De Maria.

Bibliography

Antonella Mampieri, Giacomo de Maria (1760-1838), I and II, Pàtron publisher in Bologna, 2020

For photographs we thank Alberto Martini, Giancarlo Nicolino, the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.