Christo, one of the greatest artists of the last 60 years, left us yesterday at the age of 84. Few others like him and his wife Jeanne-Claude, with whom he worked as a couple all his life, have made their mark on twentieth-century art. In this article, therefore, we have decided to look back over his career through ten key masterpieces, which should be known in order to begin to get in touch with the art of a genius of the 20th and 21st centuries.

1. Wrapped Bottle (1958; fabric, rope, lacquer, paint, sand, bottle; 20.3 x 7.6 cm; Carbondale, Kimiko and John Powers Collection)

Christo matured the idea of wrapping objects as early as his arrival in Paris in 1958 at the age of twenty-three. A forerunner of Nouveau réalisme, the movement that would be founded a few years later (and which Christo himself would join in 1963), he initially saw wrapping as a means of learning more about the object and reducing it to an analysis of its essential qualities: form, materials, surface appearance (so much so that wrapped objects were often exhibited alongside “free” objects). The basic assumption was similar to that of Pop Art artists: any object, even the most humble, can be elevated to a work of art. On the act of wrapping itself, interpretations are varied, and Christo never gave a definition (“I don’t define art, I make it,” he had to say), without calculating that the meaning of the operation also varies on the basis of the object being wrapped, and that Christo’s own statements throughout his career have often been contradictory (for example, it happened that he claimed that wrapping has only a purely aesthetic value). A means of affirming the presence of a content through its absence, a way of limiting the aesthetic pleasure one derives from viewing an object (or, conversely, of creating a new one), an affirmation of the artist’s gesture (at a time when research on gesture by artists around the world was a hot topic), a reflection on perception: much has been written and much could be said about the wrappings, from the very first works.

|

| Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Wrapped Bottle (1958; fabric, rope, lacquer, paint, sand, bottle; 20.3 x 7.6 cm; Carbondale, Kimiko and John Powers Collection) |

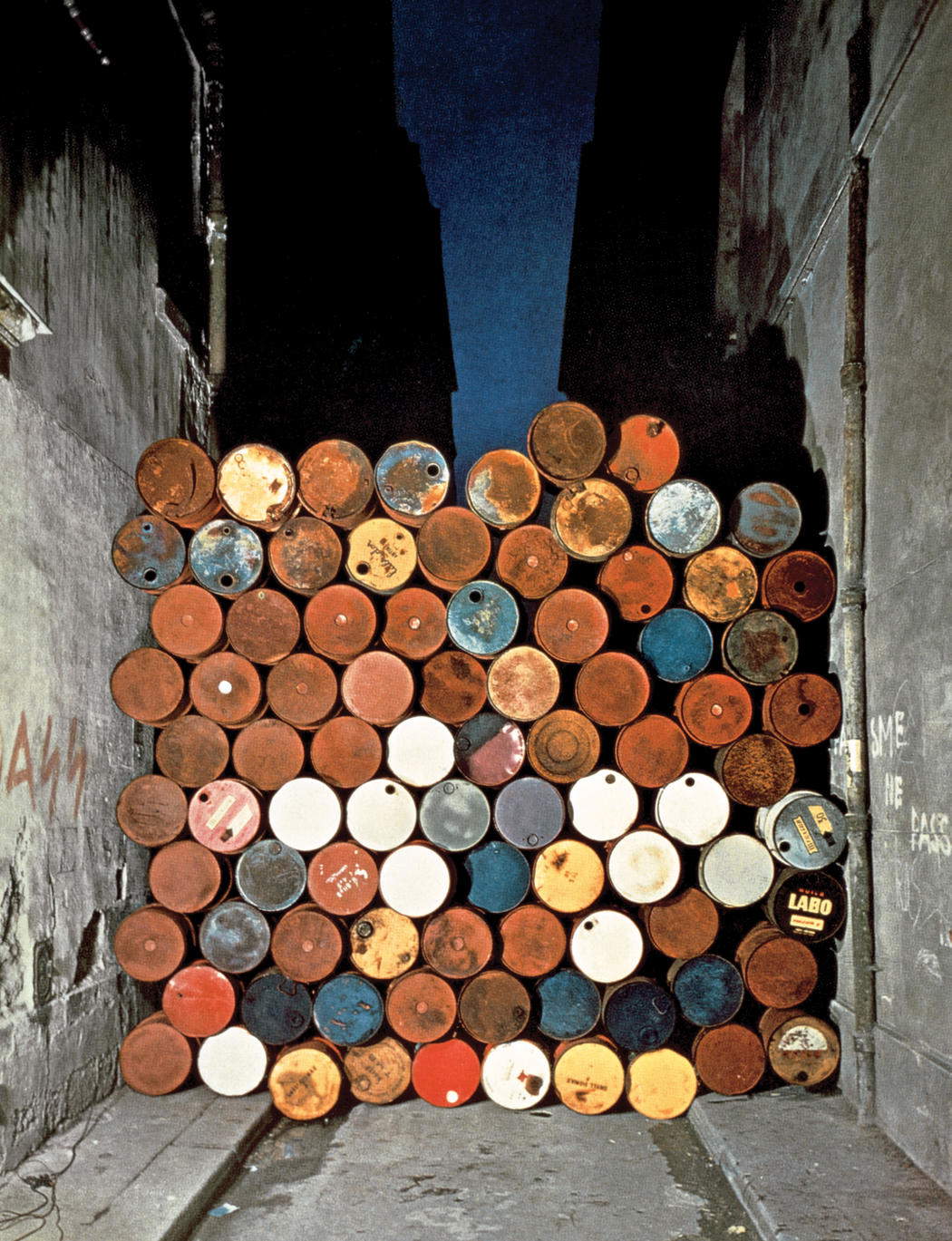

2. Wall of Oil Barrels (1962; oil barrels, 420 x 400 x 50 cm)

Made on June 27, 1962 in Paris, on the rue Visconti near the bank of the Seine, the Wall of Oil Barrels is Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s first major project, the one with which they came to the attention of the general public. The couple had been working with oil since 1958: it was a cheap and easy-to-source material, and it represented a sort of “big picture” version of the bottles and cans with which the two artists had begun their work. The barrels were stacked in Gentilly’s studio, where Christo could arrange them as he pleased and always experiment with new combinations. They were first exhibited in 1961, in Cologne, and the following year Christo and Jeanne-Claude had the idea of erecting their “iron curtain” on a Paris street. This “iron curtain,” the two artists wrote at the time to introduce the work, “can be used as a barricade during a period of public works on a street, or to turn a street into a dead end. And eventually this principle can also be extended to an entire area or an entire city.”

|

| Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Wall of Oil Barrels (1962; oil barrels, 420 x 400 x 50 cm) |

3. 42,390 Cubic Feet Package (1966; inflatable balloons and polyethylene envelope, 18.3 x 7.6 x 9.8 m)

In October 1966, Christo and Jeanne-Claude traveled to Minneapolis for their 42,390 cubic feet package project, the largest work to date by the pair, nearly twenty meters long and almost ten meters high. It was a work strongly based on contrasts: despite its enormous size, the total weight of the work was very low (just 225 kilograms), but still very high when one considers that the entire enormous installation is made only of casings and air. To make it, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, who enlisted the help of 147 students from the local Minneapolis School of Art, filled 2,800 inflatable balloons about 70 cm in diameter on average with air: all the balloons were then inserted into the large polyethylene casing, which was sealed with tape and secured with 914 meters of rope, and in turn inflated until it reached its final oblong shape. The 42,390 cubic meters of air were installed in a lawn on the campus of the Minneapolis Schoolf of Art with the help of a helicopter. It was, moreover, one of the first projects for which the couple experimented with ways to raise resources that they would not later abandon: selling plans and drawings to collectors and seeking private sponsorship. For this work, Christo also reserved a surprise for collectors: in fact, he created one hundred wrapped Boxes, similar to parcel post. If the collector had the unfortunate idea of opening the parcel, he would find a note inside saying “you have just destroyed a work of art.”

|

| Christo and Jeanne-Claude, 42,390 Cubic Feet Package (1966; inflatable balloons and polyethylene wrap, 18.3 x 7.6 x 9.8 m) |

4. Wrapped Fountain and Wrapped Medieval Tower (1968).

This was the first project that Christo and Jeanne-Claude carried out in Italy, in 1968, as well as one of the first major wrappings (it was the second, after the one at the Kunsthalle in Bern the previous year, although the two projects were carried out at the same time). The artists had been invited to Spoleto for the Festival dei Due Mondi: Christo was still busy with the Bern project, and Jeanne-Claude traveled to Umbria to make an inspection. It was then decided to proceed with the wrapping of two important monuments in the city, the Fortilizio dei Mulini (a tall watchtower that, being near a watercourse, also served the function of a mill, hence the name) and the fountain in Piazza del Mercato. The wrap-up is one of the most significant in Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s career for several reasons. As for the tower, it was one of the oldest monuments in the city (as well as the oldest building that Christo and Jeanne-Claude have ever wrapped), and wrapping it in a modern envelope meant bringing together ... two different worlds, like the ones that give the festival its name. The seventeenth-century fountain, on the other hand, guaranteed an alienating effect, because its shape resembles that of a baroque church façade, so that seeing it completely wrapped in the white fabric, those who were not from Spoleto did not quite understand what was underneath the wrapping.

|

| Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Wrapped Fountain and Wrapped Medieval Tower (1968) |

5. Valley Curtain (1970-1972)

Valley Cur tain is the large-scale project that Christo and Jeanne-Claude carried out on August 10, 1972, in Rifle, Colorado, where they installed an enormous 18,600-square-foot orange tent between two mountain ranges that run parallel. A team of more than a hundred people was needed to make the monumental installation, consisting of skilled workers, collaborators recruited for the occasion and students from art schools who joined 27 ropes to secure the heavy fabric, suspended at a height of 111 meters at the ends and 55 meters in the middle. The project, in its various stages (planning, fundraising, making the material, and so on) took 28 months to complete, and 28 were also the hours that the work endured, since a strong wind arose the next day, causing fears for the safety of the area, and so the large curtain had to be removed: it was nonetheless the most impressive work of Land Art that Christo and Jeanne-Claude had created up to that time. In 1974, filmmakers Albert and David Maysles made a 28-minute documentary about this work, entitled Christo’s Valley Curtain: it earned an Oscar nomination for best documentary short.

|

| Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Valley Curtain (1970-1972). |

6. The Bundled Reichstag (1971-1995).

This is probably the most famous of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s wrap-arounds and the one that took the longest to complete, since twenty-four years elapsed from its conception in 1971 to its execution in 1995. The idea, as per Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s typical modus operandi, was to wrap Berlin’s Reichstag, the seat of the German Parliament, in polypropylene fabric: the operation would also be cloaked in considerable political overtones (“wrapping a symbol of power such as the Reichstag,” Vittorio Sgarbi said at the time, commenting on the work, which had a wide media impact, “means highlighting and simultaneously tearing down that symbol”), but again Christo did not provide particular insights into the interpretation of the work (a trait that would characterize his entire career). In the official presentation of the work, we read only a brief reference to the fleeting nature of human works: “fabric, like clothes or skin, is fragile: it translates the unique quality of transience.” One hundred thousand square meters of fabric and 15 kilometers of rope to secure it were needed to wrap the Reichstag. The work, as had been the case with all the projects that had preceded it and as would be the case with subsequent ones, was entirely financed through the sale of the drawings and preparatory studies. In the end, the wrapping up lasted fourteen days, during which instead of the German Parliament Berliners could see a silvery mass that suggested only the shape of the building.

|

| Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The Bundled Reichstag (1971-1995) |

7. The Gates (1979-2005; 7,503 fabric and vinyl elements, height 487 cm each)

Another project chased for years, since it was envisioned in 1979 but did not see fruition until 2005. It is another famous land art intervention: the installation of 7,503 fabric panels in New York’s Central Park on Feb. 12, 2005. 7,503 nearly five-meter-high “doors” composed of a vinyl structure holding orange fabric sheets, arranged 3.65 meters apart. A massive effort was required to create the work: seventeen companies made the necessary materials, and on the day of installation 600 workers, divided into teams that each had to take care of 100 doors, ensured the rapid completion of the installation. Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s idea was to evoke the forms of nature with this long snake of gates winding along Central Park: for those who found themselves walking in the park (the gates remained there for sixteen days) it was like passing under the branches and leaves of many trees, while those who admired The Gates from the skyscrapers around Central Park had the impression of seeing an orange river appearing and disappearing among the branches of the trees.

|

| Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The Gates (1979-2005; 7,503 fabric and vinyl elements, height 487 cm each) |

8. Surrounded Islands (1980-1983).

In 1980, Christo and Jeanne-Claude came up with the idea of surrounding eleven islands in Biscayne Bay, across from Miami, with garish pink fabric: it is one of the most celebrated land art works in art history. The installation was finished on May 7, 1983, by which time the 603,870 square feet of floating pink polypropylene fabric had wrapped the shoreline of all the islets, remaining there for a couple of weeks. The two artists chose pink because they found it to be a color that fit well with the tropical vegetation of the uninhabited islands, and it was also in harmony with the colors of the Miami sky and the waters of the bay. At the same time, however, it was an unnatural color that was meant to denote the artificial nature of the intervention, even if it was able to evoke certain colors of the environment (those of the red flamingos typical of Florida, or the colors of sunsets over the sea, but also the pink of Florida construction). The creation of the installation also required the input of a marine biologist (Anitra Thorhaug), two ornithologists (Oscar Owre and Meri Cummings), an ethologist (Daniel Odell), who had to verify that the work would not have destabilizing impacts on the local fauna, and several engineers who studied how to make sure that sea currents and wave motion would not damage the work. The fabric was attached to rods that were tied to anchors that allowed the work to remain stationary in place.

|

| Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Surrounded Islands (1980-1983) |

9. The Umbrellas (1984-1991)

The only work created by Christo and Jeanne-Claude in two countries at the same time (the United States and Japan), it was intended to highlight the similarities and differences (in the way of life and the way of relating to the landscape) of two nations so far apart. Installation operations for the 3,100 umbrellas began simultaneously on October 9, 1991, in Ibaraki, Japan, and near the Tejon Pass in California, about 100 kilometers north of Los Angeles. Fabrication of the umbrellas (all made in Bakersfield, California) began in 1990: they were large, six-meter-high artifacts, with a diameter of more than eight meters, that remained installed for two weeks. For this installation, Christo and Jeanne-Claude did not accept sponsorship, preferring to raise the $26 million needed for construction by selling drawings and plans alone. “In the precious and limited space of Japan,” reads the presentation of the work, “the umbrellas were placed intimately, close to each other and sometimes positioned to follow the geometry of rice fields. In the lush vegetation watered by water year-round, the umbrellas were blue. In the vastness of California’s uncultivated pasture lands, the configuration of umbrellas was bizarre and spread out in every direction. The brown hillsides were covered with blond grasses. In that dry landscape, the umbrellas were yellow.”

|

| Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The Umbrellas (1984-1991) |

10. The Floating Piers (2014-2016)

In Italy, Christo’s name will always be linked to the impressive project carried out in 2016 on Lake Iseo: one hundred thousand square meters of yellow fabric to create a large pier that connected the town of Sulzano to Monte Isola and the island of San Paolo. Citizens and tourists had the opportunity to walk on the water, having an experience that is hard to forget. The work remained on the lake from June 18 to July 3, 2016, after which all the materials were dismantled and recycled.Like all of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s (who had since passed away) projects, the Floating Piers on Lake Iseo did not charge an entrance fee, nor did they require inaugurations, reservations or ceremonies. For Christo, the Floating Piers were “an extension of a road” and belonged to everyone. Although the realization is 2016, Christo and Jeanne-Claude had dreamed of it since the 1970s.

|

| Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The Floating Piers (2014-2016) |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.