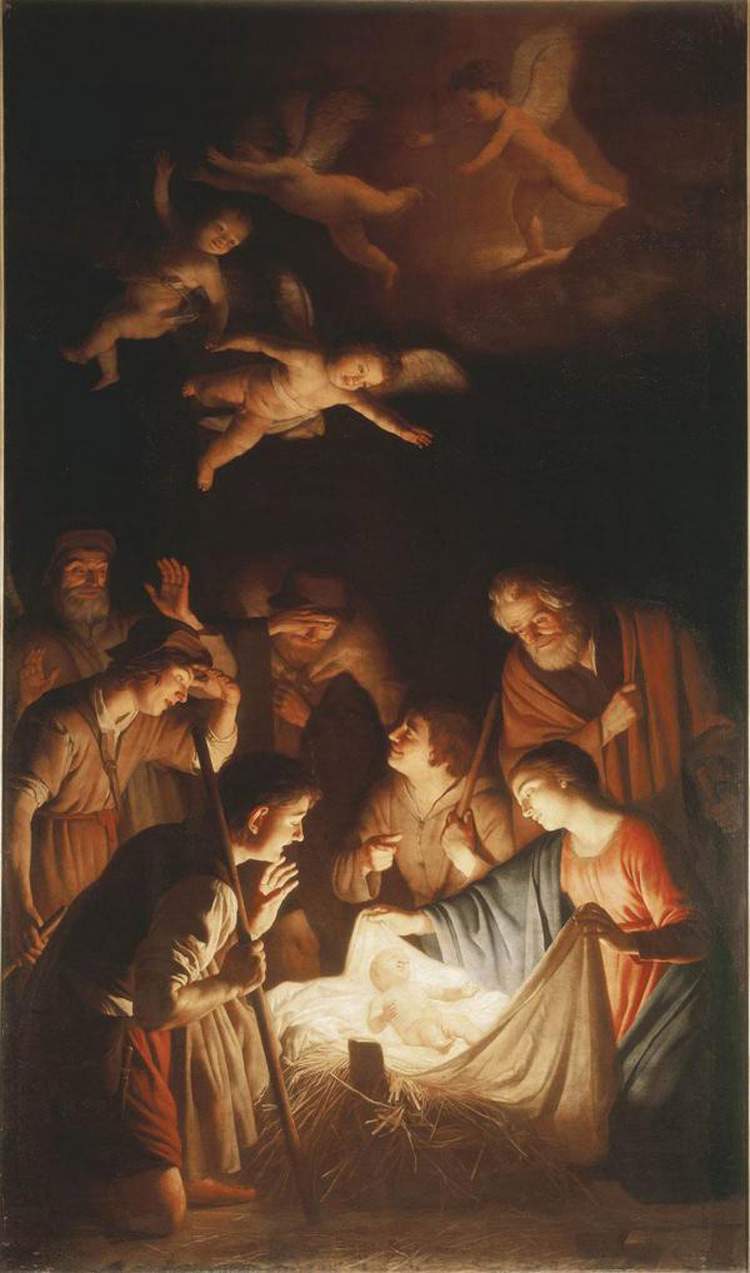

Gerrit van Honthorst's wonderful nocturnal nativities preserved in the Uffizi.

Among the most beautiful Nativities in the history of art is the Adorationof the Child by Gerrit van Honthorst (Utrecht, 1592 1656), also known in Italy as Gherardo delle Notti, for his penchant for painting touching and evocative nocturnal scenes. Just like this Adoration: this is a splendid nocturne, painted by the artist between 1619 and 1620, which exudes a wonderful calmness: a feeling of divine calmness seems to overflow from the entire painting, entering our hearts and minds. A muffled and almost magical atmosphere, as only Christmas night can convey.

|

| Gerrit van Honthorst, Adoration of the Child (c. 1619-1620; oil on canvas, 95.5 x 131 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

This overflowing sense of serenity is heightened if the viewer focuses on the faces of the characters depicted in the work: the four figures on either side of the canvas, namely the Madonna, Saint Joseph and two angels, are in adoration of the newly born child, who occupies the center of the scene. Mary’s gaze, like that of the other three figures depicted, is constantly turned toward Baby Jesus, who is placed on the straw of a small manger covered with a white cloth. The face of the Virgin is that of a young girl with tender, delicate features, who, with her eyes turned downward, almost half-closed, and her mouth sketching a sweet smile, worships her child, expressing the boundless love a mother feels for her little creature. While in the act of adoration, she finely lifts the two flaps of the cloth as a sign of protection: the painter probably depicted the milky moment immediately preceding the moment when the mother wraps the child with the sheet. Slightly behind the Madonna, but still on the right side of the canvas, is Saint Joseph: his face, as per the iconography decidedly more mature than Mary’s, is framed by a thick beard, but his eyes, half-closed like those of the female character, express love, joy and tenderness through an adoring good-natured expression.

The left side of the canvas is occupied by two angels with the likenesses of little boys. One dressed in a light blue robe is admiring the child (he is the only character placed perfectly in front of Jesus) and holds his hands crossed on his chest as a sign of humility; the other dressed in a yellow robe with carved and embroidered hems and a red girdle, holds his hands together and looks at the little child holding his mouth half-open in a dreamy expression. The intimate and cozy scene is enveloped in light emanating from the white cloth and the child himself and particularly illuminating the faces of the figures around him. An expedient that certainly comes from the Caravaggesque lesson: to be in the foreground both from the point of view of the composition of the painting and from the symbolic point of view are the illuminated figures in the round, whose glow spreads to the rest of the painting. It is a sacred light that, bearing in mind also the achievements of Correggio in his very famous Night today in Dresden and Luca Cambiaso in his candlelight scenes probably known in Rome (and to be exact in Palazzo Giustiniani), emanates like an artificial light from the most important character par excellence: this creates a play of light and shadow, typical of the Dutch artist’s style, capable of bringing figures on the canvas out of the darkness through an overflowing glow of light coming from a candle or a divine character. His works are mostly nocturnes with the presence of artificial or divine light sources gently illuminating the scene: hence the appellation Gherardo delle Notti.

Gerrit van Honthorst arrived in Rome presumably in 1610 and certainly knew the art of Caravaggio, indeed: he was immediately influenced by him. In early seventeenth-century Rome, artists could take two directions: either that of the academic art represented by the Academy of San Luca, which was inspired by the great artists of the past, or that of the naturalist art influenced by Caravaggio, an alternative to the official art, and more realistic. And Gherardo delle Notti chose to approach the latter immediately, becoming one of the leading exponents among the first-generation Caravaggesques.The Adoration of the Child by van Honthorst is preserved in the Uffizi Galleries, but we do not know exactly how it came there: it is first mentioned, already with reference to Gerrit, in 1784, in the inventory of the Medici villa of Poggio Imperiale in Arcetri, and a further inventory of 1796 attests to its presence in the Uffizi. However, we do not know for whom it was made, nor for what place it was intended. What we can assert with some certainty is that the Adorationof the Child is very close, in style, motifs and commonality of atmosphere, to another painting, also kept in the halls of the famous Florentine museum and made by the same artist, but which unfortunately has had a less than serene history. We are talking about the Adorationof the Shepherds made in 1619, a painting that was a victim of the terrible Mafia attack in Via dei Georgofili in 1993.

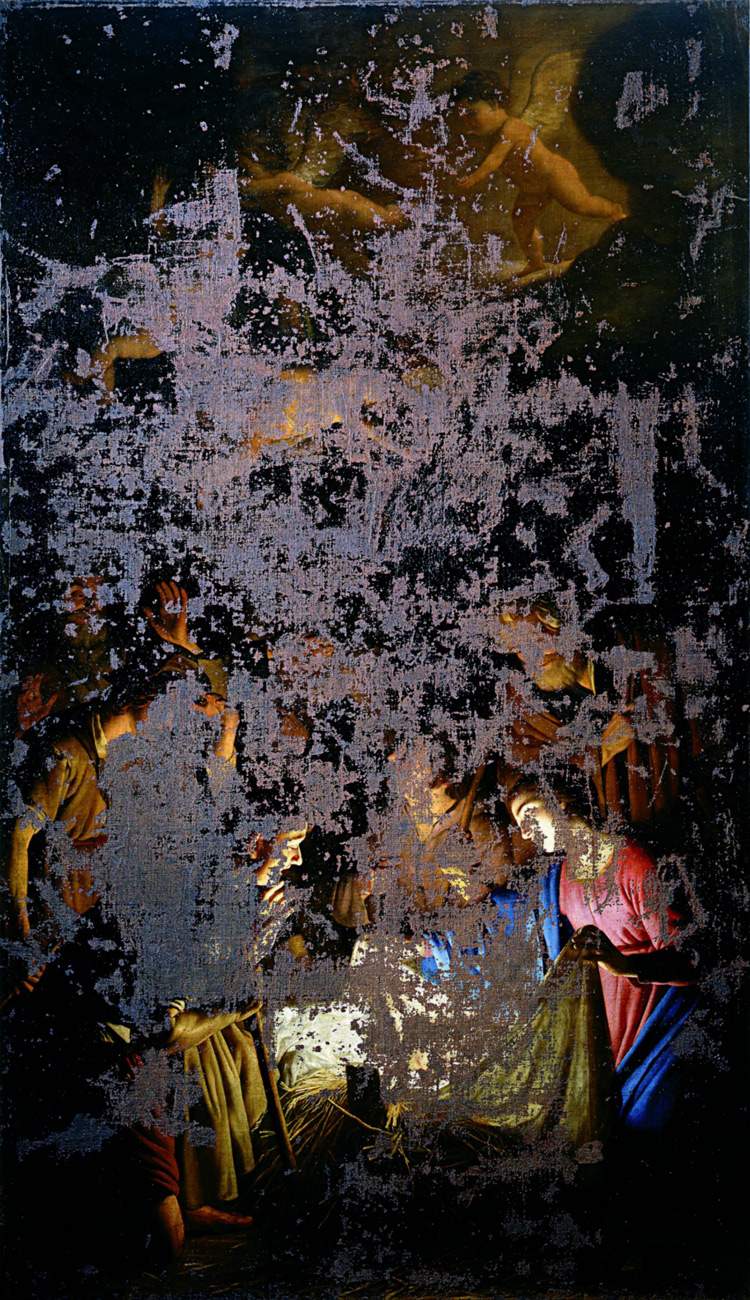

|

| Gerrit van Honthorst, Adoration of the Shepherds (1619-1620; oil on canvas, 338.5 x 198.5 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| Uffizi, the devastation caused by the bombs in the Georgofili massacre |

|

| Gerrit van Honthorst, Adoration of the Shepherds before the Georgofili massacre. |

The compositional posture of the latter is very similar to that of the Adoration of the Child, although it calls in more characters. Here, too, the Infant Jesus emanates a divine light that spreads to the other characters represented: in the right part of the canvas are placed the Madonna, who lovingly looks at the child and at the same time very delicately lifts two flaps of the white cloth on which the little child lies, and St. Joseph, who, in a posterior position to Mary, stares at Jesus with a tender, barely sketched smile. The left side of the painting is occupied by a group of shepherds who, receiving the announcement of the birth from the little angels noticeable in the upper end of the work, have flocked to adore the child. The shepherds depicted are very expressive and through their gestures communicate surprise, wonder, and tenderness. Some of them hold a hand above their foreheads, as if blinded by the dazzling light that emanates from the bed and the infant itself.

It is the latter, wrote Antonio Natali in the catalog of the major exhibition that the Uffizi dedicated to Gerrit van Honthorst in 2015 and in which both the Adoration ofthe Child and the Adorationof the Shepherds were absolute protagonists, the source of light that brightens the onlookers, obeying the image of the Word that sinneth and the light that shineth in the darkness. On the faces of the shepherds, very humble and unaware, the light emanating from the little body of Christ is reflected decisively and sharply: Grace touches them and they immediately believe. But almost nothing is left of these beautiful suggestions: the most damaged part is precisely where the figures are concentrated. If the dark night sky had kept the chromatic compactness almost intact, the flashes of light and shadow that acted on the cloths and fleshes of those gathered at the manger had dissolved. Completely gone was the figurine of the baby Jesus.

The next morning suckled, the cloth was stretched out, veiled, and transported to storage. It was believed lost forever. Nearly a decade after the massacre, it was thought that it was right to relocate the work to exactly the place where the lattentato caught it and that it should therefore be recovered in its unabraded parts through the careful, researched and patient work of restorers. In this way it would have been a kind of moral warning, or at any rate blatant proof of theancipitous human nature; for it is destructive, and yet also lovingly inclined to heal wounds; even those that it alone sinfliges. The painting, commissioned by the diplomat Piero Guicciardini, had been conceived (moreover, in accordance with the artistic ideas of the patron, who we know was strongly attracted to the naturalist painting of the time) for the main chapel of Santa Felicita, of which the noble Guicciardini family held the patronage, but in 1973 it was placed on the grand staircase that descends from the west wing of the Uffizi Gallery to the Vasari Corridor (a place ideally connected to the church, since the Corridor passes right through the pronaos of Santa Felicita), and it was there that the canvas was placed that May 27, 1993. After the aforementioned restoration, in 2003 what was left of the Adoration of the Shepherds was relocated to the usual spot.

The history and the result of these facts were reiterated in the aforementioned exhibition, the first monographic exhibition, which the Uffizi Galleries dedicated to the Dutchman Gerrit van Honthorst in 2015: Gherardo delle Notti. Whimsical Paintings and Merry Dinners. In the exhibition itinerary, one room was dedicated to the damaged painting, which, through projections and videos, was reassembled of its missing parts, and at the same time images of the destruction caused by the attack filmed inside the Uffizi were made visible. Two paintings made by the same artist and kept in the same museum, linked by the same theme and very similar composition, one of which unfortunately suffered the terrible effects of inconceivable and monstrous human action. But he never stopped spreading the beauty of his poetry.

Reference bibliography

- Gianni Papi (ed.), Gherardo delle Notti. Quadri bizzarrissimi e cenene allegre, exhibition catalog (Florence, Uffizi Gallery, February 10 to May 24, 2015), Giunti, 2015

- Gloria Fossi, Uffizi Gallery: art, history, collections, Giunti, 2001

- Mina Gregori, Erich Schleier, Painting in Italy: the seventeenth century, Electa, 1989

- Jay Richard Judson, Gerrit van Honthorst: A discussion of his position in Dutch Art, Nijhoff, 1956

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.