by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta , published on 05/08/2018

Categories: Works and artists

- Quaderni di viaggio / Disclaimer

The Mackenzie Castle is one of the most incredible buildings in Genoa: it is the realization of the dream of Evan Mackenzie, a great antiquities enthusiast, and architect Gino Coppedè.

He was just 30 years old Gino Coppedè (Florence, 1866 - Rome, 1927) when he was about to design his first major work, the one that would later grant him fame among his contemporaries and help launch his name. Coppedè, a talented but then inexperienced young man, had been noticed by the very wealthy insurer Evan Mackenzie (Florence, 1852 - Genoa, 1935), first an agent for Lloyd’s of London, and then, in 1898, the founder of a new and modern insurance company, Alleanza Assicurazioni, which still exists today.Mackenzie had been born in Florence to a Scottish noble adventurer, and was very much in love with his hometown. Here, he used to frequent the workshop of the sculptor Pasquale Romanelli (Florence, 1812 1887), whose daughter, Beatrice, had married Gino Coppedè: Mackenzie had long since moved to Genoa and intended to give shape to a dream of his own, that of seeing a sumptuous residence built that would remind him of his beloved Tuscany. In particular, Mackenzie loved about Florence its history: the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, the 16th century. He had even started a collection of Dante editions. So, even the residence should have given him the impression of living in the heart of Florence.

Mackenzie, in Genoa, had bought a property located near the ancient seventeenth-century walls, on the bastions of San Bartolomeo. It was a highly prized location: near what is now Piazza Manin, on top of a hill, from which there was a beautiful view of the city. The young Gino Coppedè had probably been introduced to him by his father-in-law, and had made a good impression. Acculturated, versatile, imaginative, well-prepared, with an excellent background of studies behind him, since he had first studied at the Professional School of Industrial Decorative Arts in Florence, and then at the local Academy of Fine Arts, as well as a profound connoisseur of the history and art of Florence, Gino Coppedè seemed the ideal architect for the project, despite his lack of experience. It was, in essence, a gamble-a gamble that Mackenzie would win triumphantly. Not least because Coppedè did not turn out to be a passive executor: it was probably he who suggested to the Scottish insurer not to restore the building he had purchased, but to build what the municipal decree mentions as “another, more grandiose building.” The first plan, which called for a renovation of the existing building, was thus radically revised, so that it was transformed into the plan for a total reconstruction, in accordance with the client’s taste, which was, moreover, in line with the fashions that had long since spread in Mackenzie’s homeland: the different revivals of the Victorian era (neo-Romanesque, neo-Gothic, neo-Renaissance) ended up merging into an eclecticism that opened up to buildings that assimilated decorative elements from the most disparate historical periods. At the end of the century, philological rigor was not sought: if anything, surprising juxtapositions dictated by personal taste were what guided the choices.

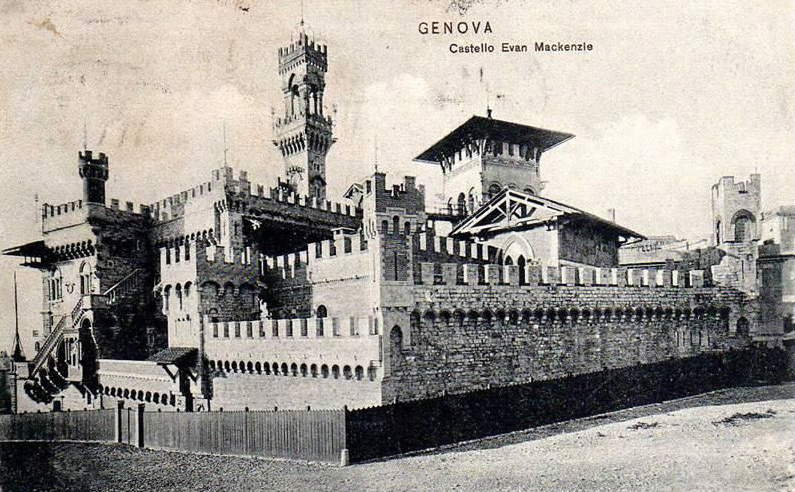

Such was the case with the building designed by Gino Coppedè, which would later become known as the Mackenzie Castle. The young architect imagined it as an ancient medieval manor, with a rectangular main body to which he added a forepart that gives the castle the appearance of being made up of two separate buildings. For the façade facing Via Cabella, Coppedè kept in mind the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena: here too we have a slightly curved façade, with floor coverings in two different materials (stone on the first floor, brick on the second floor, then stone again on the upper floors), ogival arches framing doors and windows, and Guelph merlons decorating the top floor. The façade facing the walls of St. Bartholomew, however, is much more complex. The portion closest to the sea has the structure of several fortified palaces of the Italian Middle Ages, with a severe stone facade and a diagonal staircase set against the walls: think of the Palazzo Pretorio in Prato, the Palazzo del Podestà in Castell’Arquato, the Ezzelinian Tower in Monselice, or even the courtyard of the Palazzo del Bargello in Florence. The same motif is repeated, moreover, on the adjoining side. The façade on the walls of San Bartolomeo then continues with a single-story brick element, decorated with hanging arches and beyond which the body of the building can be glimpsed, and with the last portion of the curtain wall, which ends with a turret in the center of the façade. On the short side, the side facing the sea, which casts off the robes of the fortress to assume those of the stately home, then towers the tallest tower of Castello Mackenzie, a sort of “slimmed-down version” of the Tower of Arnolfo in Florence or the Torre del Mangia in Siena.

|

| Mackenzie Castle in a period photo. |

|

| From left to right: Prato, Palazzo Pretorio; Castell’Arquato, Palazzo del Podestà; Monselice, Ezzeliniana Tower. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The Tower of Arnolfo in Florence and the Torre del Mangia in Siena. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Luigi De Servi, Portrait of Ewan Mackenzie (1902; oil on canvas, 136.5 x 136.5 cm; Genoa, Galleria d’Arte Moderna) |

|

| Gino Coppedè |

The Mackenzie Castle was not the first building of the “revival” genre in Genoa: a few years earlier, in 1892, the Castello d’Albertis, home of the explorer Enrico Alberto d’Albertis (Voltri, 1846 - Genoa, 1932), who had entrusted the design of his mansion to a team of architects and engineers supervised by Alfredo d’Andrade (Lisbon, 1839 - Genoa, 1915), was in fact inaugurated. However, Castello d’Albertis and Castello Mackenzie are separated by profound differences. For the Castello d’Albertis, in fact, the designers wanted to be as philological as possible by devising a building inspired exclusively by the dwellings of the Genoese Middle Ages, with quotations from the Palazzo San Giorgio, the Embriaci tower, and the houses of the Dorias, while also ranging beyond the region (for example, there are elements inspired by the cloister of San Colombano in Bobbio) but without transcending the reference period. Castello Mackenzie, on the contrary, is transversal with respect to the evi: there are medieval elements, others Renaissance, still others neoclassical, not to mention the many decorative elements in keeping with the fashions of the time, such as the wrought-iron spiral staircases with geometric patterns typical of the Art Nouveau style. Coppedè did not look to the theories of John Ruskin, William Morris, Eugène Viollet-le-Duc: he was not interested in being philological. He cared, if anything, about being eclectic, and at the same time modern. Besides, he also found it much more amusing: at the end of the work, in an interview given to the Genoese newspaper Il Caffaro, he was to say, with that typically Tuscan irony that characterized him, “I fiddled with it a bit.” A line that summed up well the ideas that had led to the birth of Castello Mackenzie.

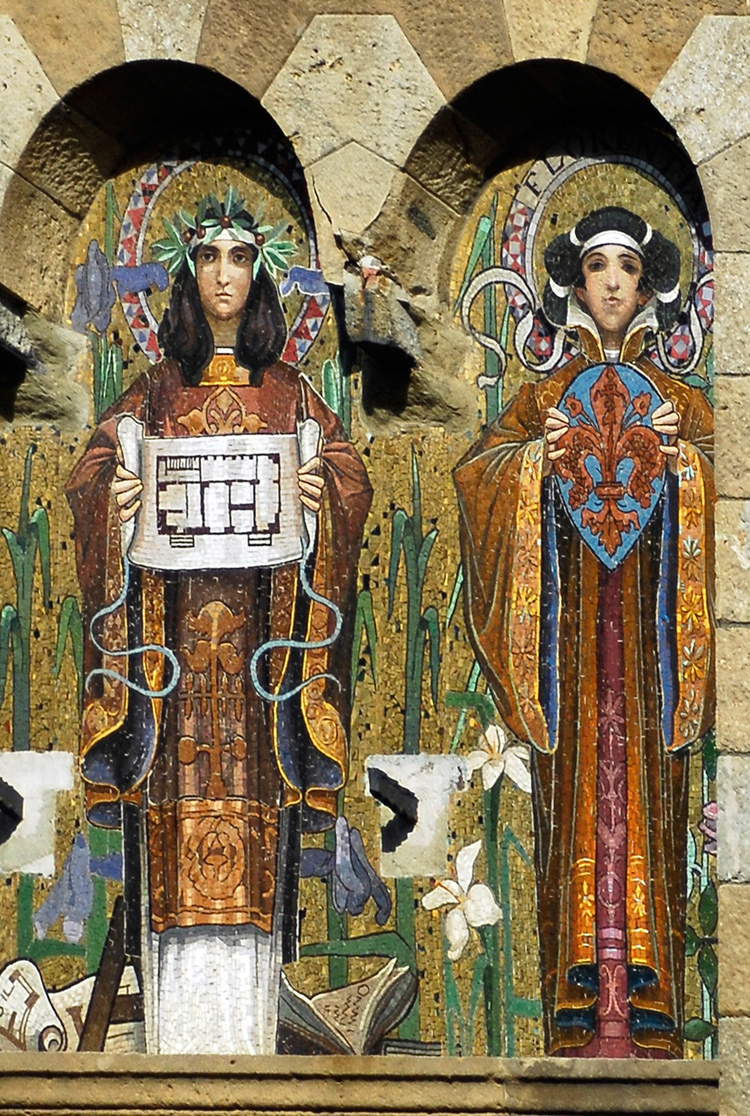

However, “dabbling” with the Castle did not mean that he considered the enterprise to be a game. On the contrary: in order to complete such a challenging work quickly (and consider, after all, that it was the project of a rookie architect, barely 30 years old, and who had no other previous achievements on his resume ), a solid and effective organization was needed. Coppedè therefore gave life to a choral work, which knew how to involve and enhance (in agreement, this time, yes, with the ideas of Morris and others) the craftsmanship, guaranteed by different manufactures, all committed to the success of the project by providing sculptures, mosaics, glass, iron elements, furniture and whatever else. The “lead” workshop was La Casa Artistica, the workshop led by Gino’s father, Mariano Coppedè (Florence, 1839 - 1920), a skilled cabinetmaker who was responsible for supplying several pieces of furniture to the Mackenzie Castle. Coordinated by the Casa Artistica, many other workshops, Tuscan and otherwise, then moved. Ceramics were supplied by the Cantagalli manufactory in Florence, which specialized in making terracottas inspired by Della Robbia sculptures. The stained glass, on the other hand, was handled by the Florentine De Matteis manufactory, one of the best Italian workshops in the production of medieval-inspired stained glass. Iron elements were commissioned from Officine Michelucci of Pistoia, the Checcucci manufactory of San Gimignano, and the firms of Giacomo Mantero of Genoa and Federico Pinasco of Recco. The same sandstone with which the walls were covered came from Tuscany. Finally, mosaics were requested from the Musiva company of Venice.

|

| Wooden fireplace. Ph. Credit Cambi Auctions |

Thus, even for the interior decorations, Coppedè pandered to Mackenzie’s taste (as well as his own) by drawing on the great Tuscan tradition, which the architect felt was his own and toward which he nurtured a deep passion. Quotations, reproductions, free reinterpretations, surprising juxtapositions of elements even far apart in time amaze those who find themselves walking through the halls of the Castle, but at the same time they harmoniously coexist with the specifications of a modern residence capable of offering every kind of comfort to those who lived there: the entire castle was from the very beginning equipped with an electrical network capable of reaching all rooms, and the same was true of the central heating system, and there was even a large elevator connecting the basement floors to the second level of the building, and a heated indoor swimming pool, complete with sauna. An architecture inspired by the past was, however, supposed, according to the latest theories, not to lack any modern conveniences for the resident. Conveniences, however, well concealed by the vibrancy of decorative elements. Wrote Rossana Bossaglia, author together with Mauro Cozzi of an important monograph on the Coppedè, fundamental to their historical relocation: “With an exuberant and eclectic mixture of styles we see the ’Ravenna’ character of the mosaics, the Florentine-Thirteenth-century and Renaissance setting of the building and furnishings, the Sienese imprint of the soaring tower, which recaptures the forms of the Torre del Mangia, the early medieval tone of many interwoven motifs , the stubborn and insistent taste for the ancient fragment, true or false, and for the composition of pieces of different stylistic nature, Roman, Etruscan, 15th-century, medieval Coppedè qualifies the building and satisfies the needs of its wealthy and intellectual owner.”

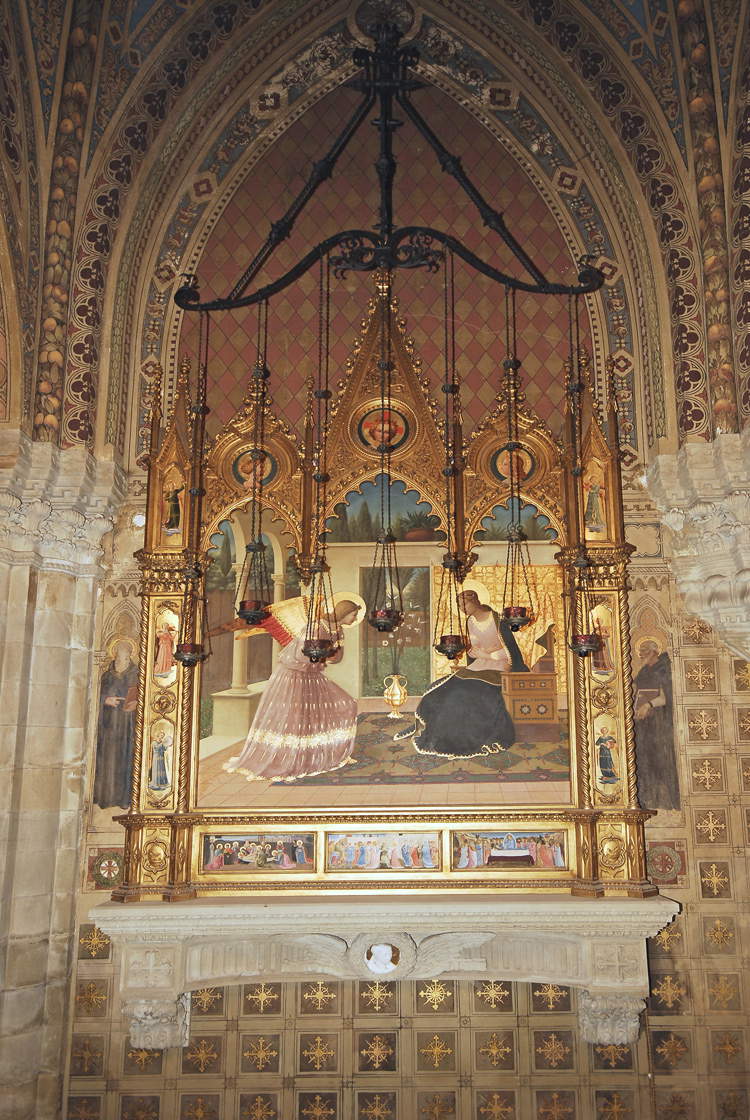

To walk through the halls of Castello Mackenzie is almost to embark on a journey through art history: a journey that mixes together authentic pieces, such as ancient Roman archaeological relics embedded in the walls, and expertly imitated pieces (the production of imitations, which were also sometimes used to orchestrate scams against wealthy foreign collectors, although this is obviously not the case at Castello Mackenzie, was particularly flourishing at the time) scattered throughout the Castle and combined to evoke a set of sensations, an atmosphere dear to the patron, to give substance to the idea that saw craftsmanship as the most important garrison of Tuscan artistic tradition. The blends already begin in the atrium, covered by cross vaults supported by mighty marble columns, decorated at the top by capitals with animals and phytomorphic motifs reminiscent of those in Romanesque cathedrals, and at the base by lions and griffins resting on plinths. Next to it, the statue of a neoclassical Venus introduces the visitor to the monumental staircase, enclosed by Renaissance balustrades, which accompanies him through the rest of the journey. The itinerary can then continue to the neo-Gothic chapel, where there are the splendid inlaid wooden stalls, of 14th-century inspiration, fabricated by La Casa Artistica in imitation of the choirs of Tuscan churches, and the large pipe organ, or to the outside loggias, on whose walls have been affixed the glazed terracotta of imitation Della Robbia produced by the Cantagalli firm, and again in the scenic Castle caves (with real stalactites arriving perhaps from Postumia, and reinforced with cement), where to our amazement we can admire a reproduction of the Venus de Milo.

The rooms of the castle, beginning with the halls and vestibules, also abound with sumptuous works of art, which constitute one of the prominent elements of Mackenzie Castle’s decoration, and contribute to Evan Mackenzie’s ambitions. The best known work is probably the wall painting depicting the construction of the Castle Tower: Renaissance-inspired (the characters seem to have come out of a painting by Ghirlandaio, while the atmosphere and the sky take on a Venetian air), it was done by the young Carlo Coppedè (Florence, 1868 - 1952), brother of Gino, who wanted to immortalize the patron in the lower part of the work, Evan Mackenzie, who, dressed in blue according to 15th-century fashion, arrives at the designers’ table to check on the progress of the work, and his brother Gino, whom we see with a long black beard as he shows the drawing of the Tower to his wealthy client. All while behind, against the backdrop of the Ligurian Sea, work is in full swing, with workers climbing scaffolding, others sawing building materials, and still others carrying stones and bricks. The atrium, on the other hand, is decorated with a mural painting depicting a procession of soldiers in a medieval Genoa: the work is heavily ruined and does not read well, but it was probably the intention of the author and commissioner to use easily perishable materials to make the effect of time acting on the image more realistic. In the chapel it is then possible to find a splendid Annunciation that is itself a mixture of elements taken from different painters: the figures and composition recall Beato Angelico, the vase between the archangel Gabriel and the Virgin is taken from Simone Martini’sAnnunciation now in the Uffizi, and the almost stylized trees silhouetted behind the loggia recall the works of Alesso Baldovinetti. Important, then, is the set of sculptures: we have already mentioned the reproduction of the Venus de Milo and the neoclassical Venus, but walking around the castle it is possible to encounter many other works in marble, including a St. George imitating Donatello ’s celebrated statue made for Orsanmichele on behalf of the Arte dei Corazzai, and a relief depicting The Wayfarer and the Fountain, with a beautiful young woman swathed in fluttering Art Nouveau veils squeezing a bunch of grapes into a cup presented to her by the knight: is a work, dated 1901, by sculptor Edoardo de Albertis (Genoa, 1874 - 1950), among the leading artists of the Genoese scene at the time.

|

| The Annunciation in the chapel. Ph. Credit Cambi Auctions |

|

| Carlo Coppedè, The construction of the Mackenzie Castle tower (c. 1900-1902; wall painting; Genoa, Mackenzie Castle). Ph. Credit Cambi Auctions |

|

| Detail of the painting of the construction of the castle tower with Gino Coppedè illustrating the project to Evan Mackenzie. Ph. Credit Cambi Auctions |

|

| The Saint George. Ph. Credit Cambi Auctions |

|

| Edoardo de Albertis, The wayfarer and the fountain (1901; marble; Genoa, Castello Mackenzie). Ph. Credit Cambi Aste |

For Gino Coppedè, Castello Mackenzie, which was finished in the space of a few years (it took on its final appearance as early as 1902, although it was inaugurated later), represented an authentic triumph and the promising beginning of a long career, which would consecrate him as one of the greatest Italian architects of the early 20th century. Newspapers, especially local ones, loudly praised his work, interviewed him, and took an interest in his work. In one of her essays, scholar Micaela Giumelli reports the judgment of a newspaper that appreciated Castello Mackenzie especially for the Tower, which was described as “deserving of special mention,” a construction “from the top of which one can discover the surrounding lands and the enchanting gulf for many hundreds of kilometers,” another newspaper addressed praise to the “magnificent tower with daring lines,” which “lorded over the city and the valleys, hailed by the distant sea and the mountains.” Still others wrote that “in the ornaments of the capitals in the balustrades of the balconies one would say one could rethink a modernized Bernini, a Bernini of our time, who prefers to crown the Corinthian some beautiful female faces instead of the classical laurel and oak leaves.” To the press Coppedè was, in essence, a new Bernini, and the Mackenzie Castle was an “extraordinary object and in magnificence and paradoxicality,” or, to use a definition given by another newspaper of the time and later taken up by many of those who described the wonders of this incredible building, a “king’s whim.”

The Mackenzie Castle had in fact sanctioned the birth of the so-called Coppedè style-a style, however, that is difficult to pin down, as Emanuela Brignone Cattaneo well specified. “It is neither Neo-Gothic nor Renaissance, it is not ornamental Art Nouveau, but of all of them one finds a hint, a revival in a very personal key. An eclectic style used unrestrainedly, which was fully adapted to the taste of the patron.” A language particularly suited to the rich bourgeoisie, which, in Italy and in Europe, was gaining increasing social weight and was seeking its own cultural identity, in line with the status it had achieved: an operation in which the recovery of the past played, at least in Italy (a young state, which had been formed for a few decades) a fundamental role. Coppedè invented a style that thus procured him several patrons, but his placing himself far from both theAcademy and the avant-garde was also at the root of the heavy criticism he would later attract, so much so that, for a long time, the expression “Coppedè style” assumed a negative meaning: however, more recent studies, such as the one, quoted above, by Rossana Bossaglia, have contributed to placing the art of the great Florentine architect in a more appropriate position. His art, moreover, guaranteed him great success: after finishing the Mackenzie Castle, Coppedè received many other commissions, managing to build up a circle of wealthy clients and going so far as to construct in Rome a complex of buildings still known today as the “Coppedè District.”

As for Evan Mackenzie, he continued to reside in the Castle, along with his family, until his passing in 1935. Four years later, his daughter Isa sold it to a real estate agency. Later occupied during World War II, first by the Germans and then by the Allies, after the war it became the headquarters of a local Carabinieri command, and in the 1960s and 1970s it was home to the Rubattino Gymnastics Society, which used it as a gymnasium. In 1986 it was purchased by the U.S. collector Mitchell Wolfson Jr. who restored it starting in 1991 (in the years when it was used as a gymnasium, in fact, the Mackenzie Castle experienced considerable deterioration), and then, in 2002, sold it to the Cambi Auction House, of which it is still the home today. So, a place where art is still alive today and which, exactly as at the time it was built, never ceases to amaze those who visit it.

Reference bibliography

- Francesca Mazzino (ed.), Historic gardens of Liguria: knowledge, redevelopment, restoration, San Giorgio, 2006

- Giorgio Croatto (ed.), Castles on land, in water and... in air, proceedings of the international conference (Pisa, May 2001), University of Pisa, 2002

- Emanuela Brignone Cattaneo, Genoa: historic buildings and grand mansions, Allemandi, 1992

- Annalisa Maniglio Calcagno, Gardens, parks and landscape in nineteenth-century Genoa, Sagep, 1984

- Rossana Bossaglia, Mauro Cozzi, I Coppedè, Sagep, 1982

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.