by Ilaria Baratta , published on 03/10/2018

Categories: Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

Giuseppe Arcimboldo's art, which marvels and amazes the beholder, has its roots in the naturalistic studies of the 16th century. This article explores the subject in depth.

We are in Milan at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries. The duchy of Ludovico Sforza known as the Moor (Vigevano, 1452 - Loches, 1508) marked the city’s most culturally and artistically flourishing period, which saw in its territories the coming and going of many artists, whose innovations and experiments enabled them to play a significant role in the history of art and humanity. One thinks of Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519), who spent many years of his life here, at the court of Ludovico il Moro, from 1482 to 1499. The genius had moved to Milan, bringing with him from Florence his naturalistic studies, particularly botany, which he developed had decisively influenced the city’s cultural and artistic environment. This earned the latter the title of the cradle of naturalism: art became more than ever based on the study anddirect observation of nature.

One example is the vault of the Sala delle Asse in the Castello Sforzesco, created in 1498 by Leonardo: an arbor made of mulberry fronds, also called jasmine, an allusion to the Duke of Milan. Naturalistic studies were perpetuated by pupils of the Da Vinci genius, including Francesco Melzi (Milan, c. 1491 - Vaprio d’Adda, 1568/70), Bernardino Luini (Dumenza, c. 1481 - Milan, 1532), Ambrogio Figino (Milan, 1553 - 1608), Cesare da Sesto (Sesto Calende, 1477 - Milan, 1523), who owned a number of books containing drawings by their master that testified to Leonardo’s great attention and careful research in that field.

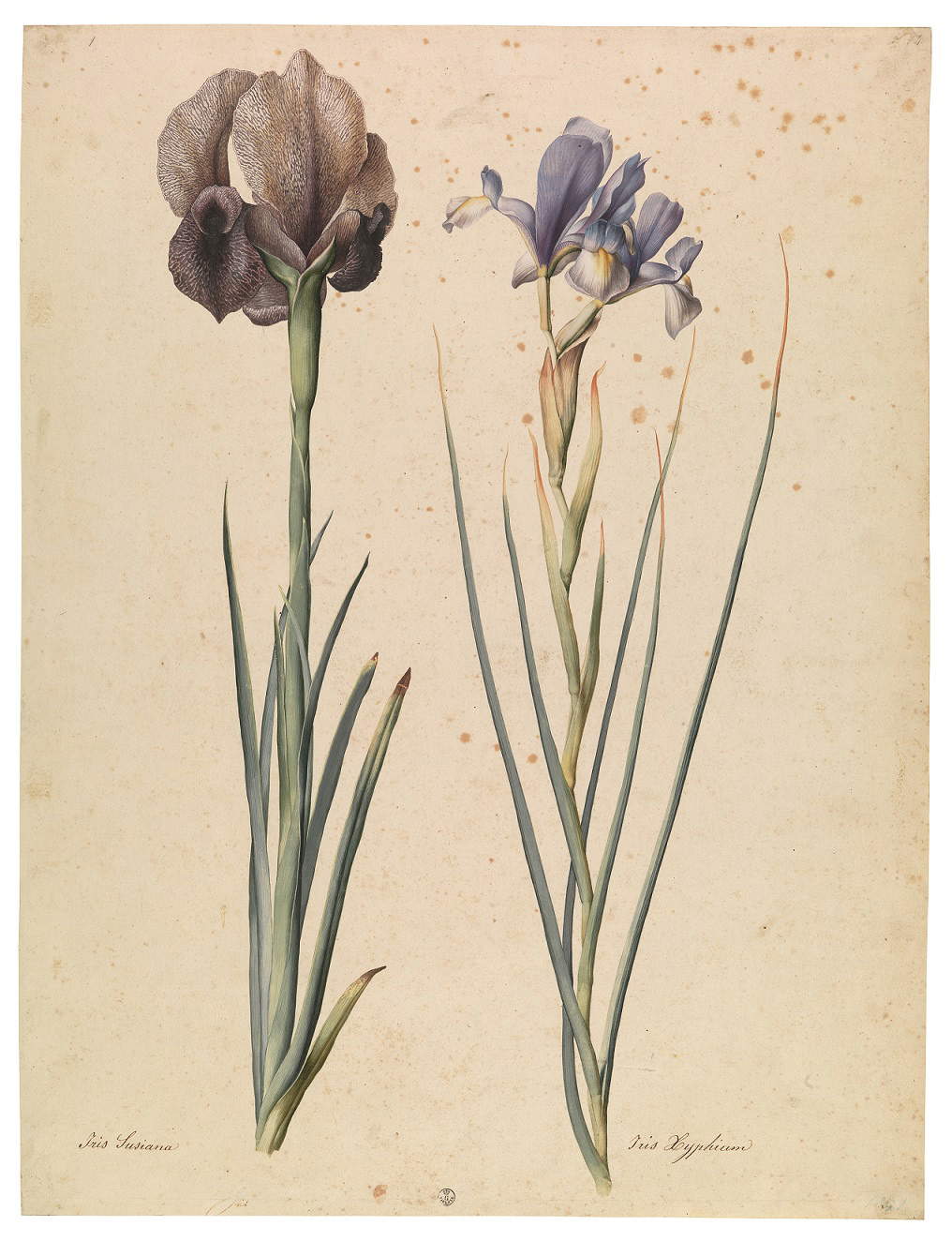

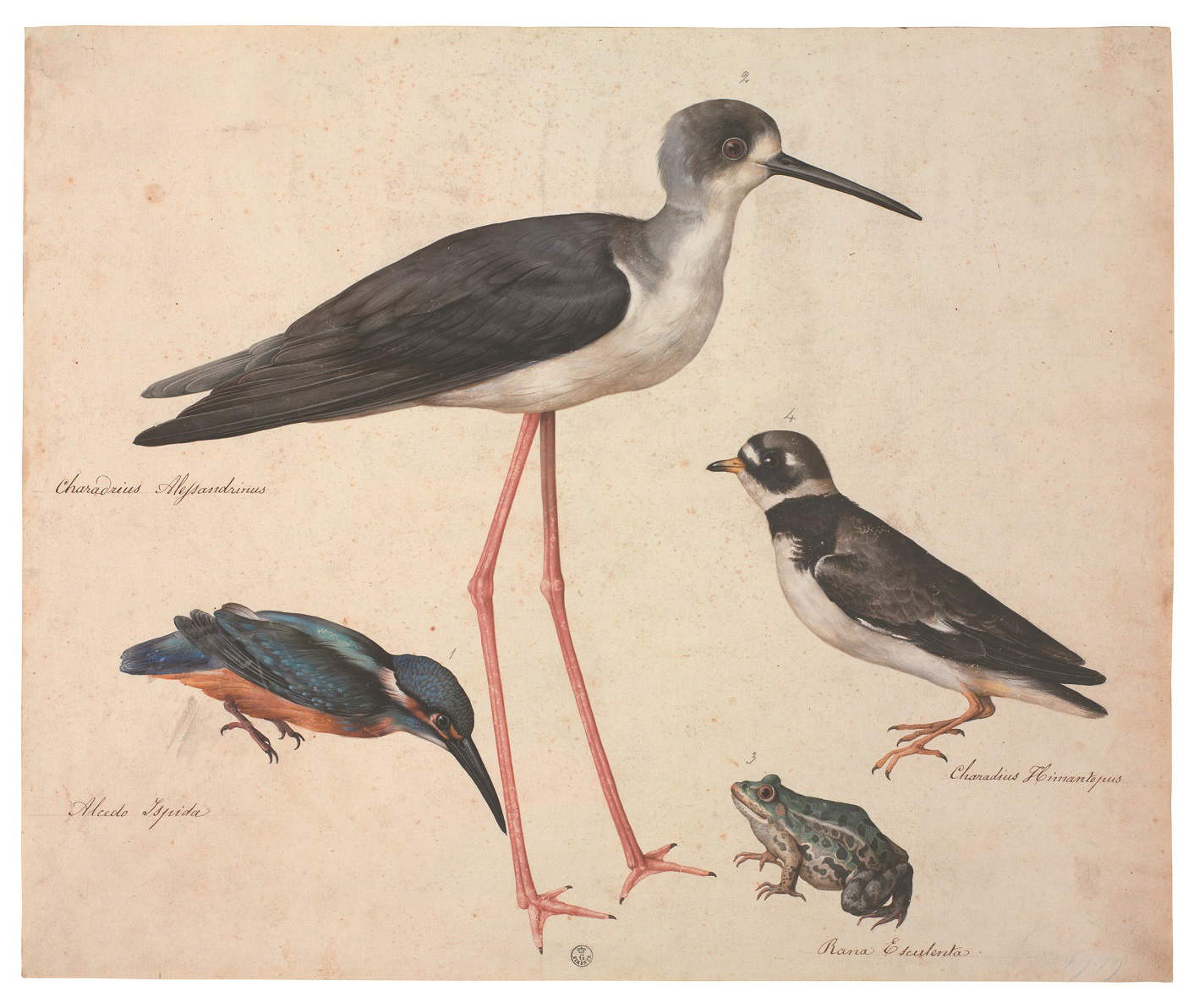

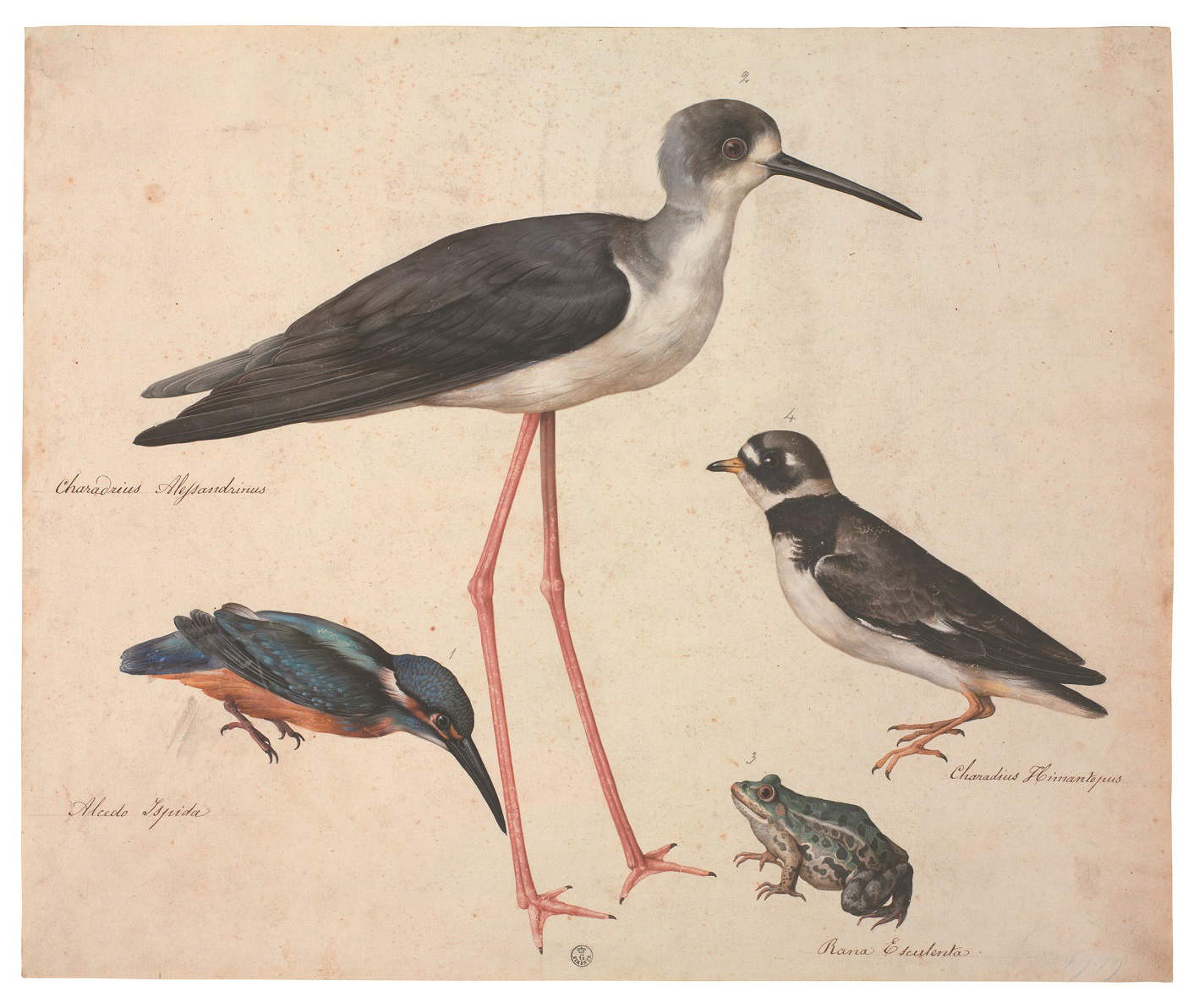

However, in reality, this in-depth interest in nature, both flora and fauna, was not the absolute prerogative of the city of Milan: in fact, at that time, scientific investigations were developing throughout Europe, but especially the natural sciences, which were constantly expanding thanks to the new geographical discoveries, which had led to the identification of numerous animals and plants hitherto unknown and which therefore aroused an even more lively interest on the part of scholars and intellectuals in general. Study and knowledge came through scientific illustrations-a new tool based ondirect experience for exploring nature and all that comprised it, including man. Therefore, a particular phenomenon arose, which consisted of scholars commissioning plates made in watercolor or tempera depicting animals, shrubs, plants, flowers, and for which artists specializing in this genre were commissioned; real collections were created, which soon became objects of desire not only of intellectuals, but also of sovereigns and nobles, who began to introduce scrolls with stupendous naturalistic images, as well as extraordinarily illustrated scientific texts, into their libraries. One could speak of the forerunners of encyclopedias, illustrated from life, often in the specialized places par excellence, namely botanical gardens, where artists depicted, in the presence of scientists and men belonging to the sphere of medical and natural sciences, cultivated plants, birds circling in aviaries, and local and exotic animals enclosed in special cages. The first botanical gardens in existence were those of Pisa and Padua, in collaboration with their universities; then followed those of Florence, Oxford, Leiden and Bologna, the latter designed and made concrete in 1568 by the physician and naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi (Bologna, 1522 - 1605): in the botanical garden of Bologna, he succeeded in growing numerous rare plants.

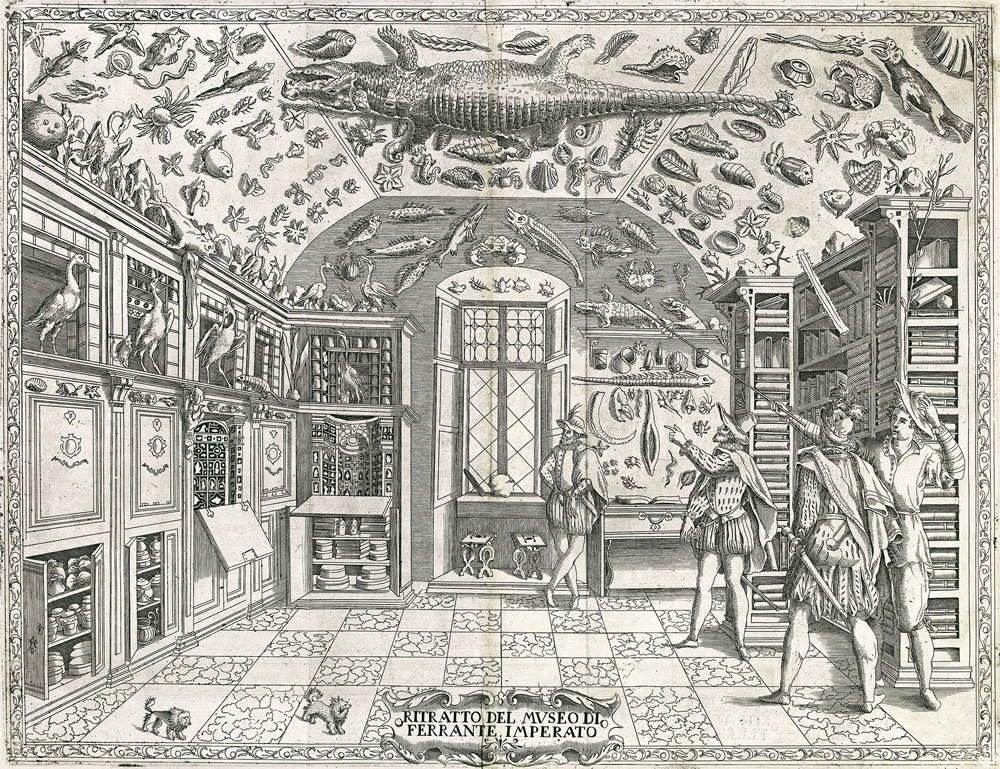

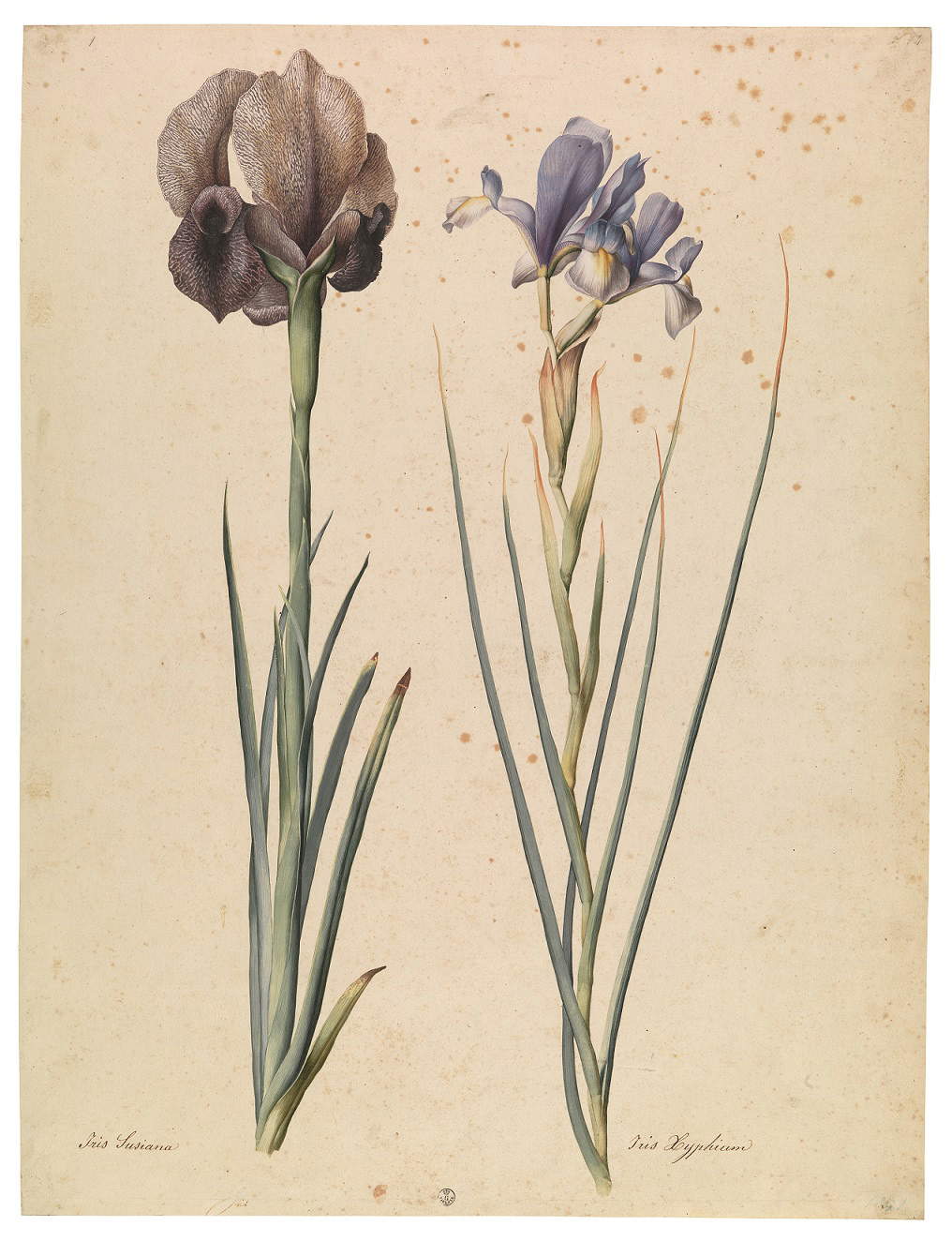

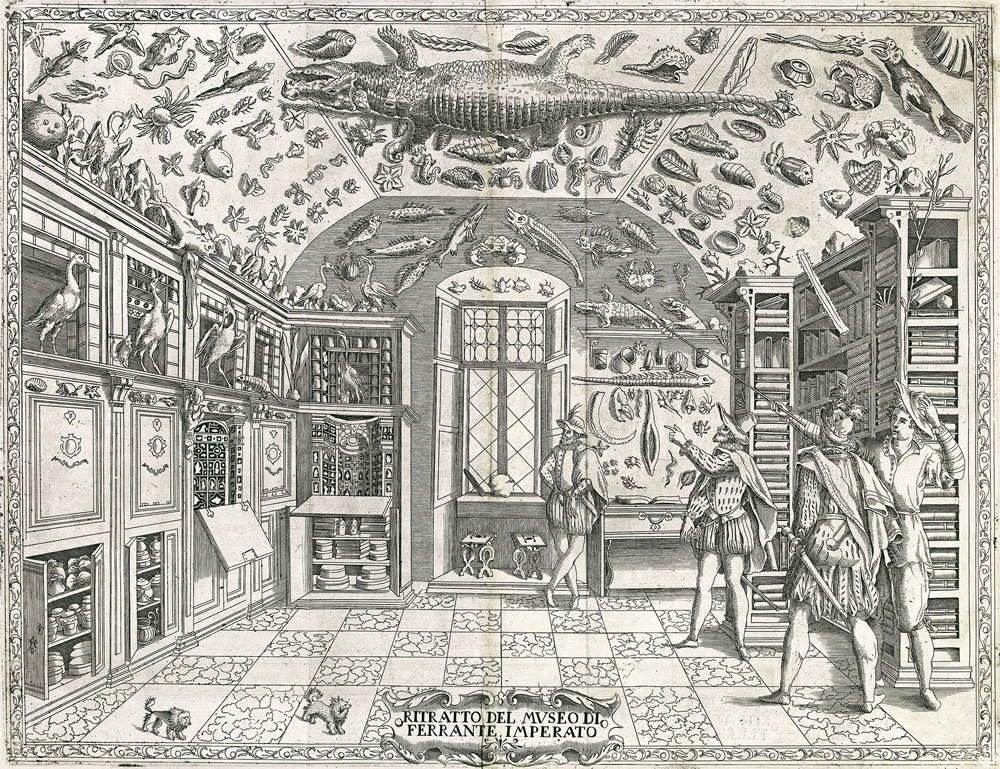

In Germany it was Albrecht Dürer (Nuremberg, 1471 - 1528) who followed this naturalistic influence, executing tempera works depicting plants, flowers and animals that seemed real from how detailed they were. Medici Florence also became a center of scientific culture and naturalistic illustrations: this is evidenced by numerous plates of fish and birds housed in the Uffizi Drawings and Prints Cabinet. An artist who specialized in this genre, and who worked in Medici-era Florence, was Jacopo Ligozzi (Verona, c. 1549 - Florence, 1627): he produced large botanical, zoological and ichthyological plates that showed not only his keen interest in the study of these species, but also an extraordinary accuracy in the smallest details, from the nuances of each leaf or petal to the chromatic variations of scales, feathers or mantles. Another widespread phenomenon in the sixteenth century in Milan, as in the whole of Europe, was the production and research of strange, unusual, “marvelous” objects, which when brought together constituted true encyclopedic bizarre collections , called Wunderkammern, literally "Chambers of Wonders." Part of such collections were both man-made and natural objects, including paintings, sculptures, instruments used in science, antiquities, mechanical objects, artifacts, animals, plants, flowers, minerals, which were intended to recreate in one or more environments the real world, as complete as possible. And the more unusual and even monstrous the objects were, the more they were desired by their collectors. The goal was to amaze, to marvel at the rarity of the objects possessed because they came from ancient times or distant realities, from newly discovered and known worlds, or because of the sophistication with which they were produced. Nevertheless, the Wunderkammern, often flanked by rich libraries, were meant to fulfill the task of leading to universal knowledge. For these two reasons, the most welcome and admired objects were those in which nature and art were combined as one.

|

| Agostino Carracci (attr.), Portrait of Ulisse Aldrovandi (c. 1585; oil on canvas, 79 x 62 cm; Bergamo, Accademia Carrara) |

|

| Albrecht Dürer, Hare (1502; watercolor on paper, 251 x 226 mm; Vienna, Graphische Sammlung Albertina) |

|

| Jacopo Ligozzi, English Iris (Iris Susiana L.), Oriental Iris (Iris Xyphium L.) (c. 1577-1587; natural black stone, polychrome pigments of organic and inorganic nature, on paper with lead-white imprimitura; Florence, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi) |

|

| Jacopo Ligozzi, Naturalistic Tables The Birds - Cavaliere d’Italia (Himantopus himantopus), Corriere grosso (Charadrius hiaticula), Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis), Green Frog (Rana esculenta) (c. 1577-1587; natural black stone, polychrome pigments of organic and inorganic nature, on paper with lead white imprimitura; Florence, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli uffizi) |

|

| Domenico Remps, Still Life in Deception (second half of the 17th century; oil on panel, 99 x 137 cm; Florence, Museo dellOpificio delle Pietre Dure) |

|

| View of Ferrante Imperato’s Museum in Naples, in Ferrante Imperato, Dellhistoria naturale , Vitale, Naples 1599 (Rome, Biblioteca Universitaria Alessandrina, Y.h.38) |

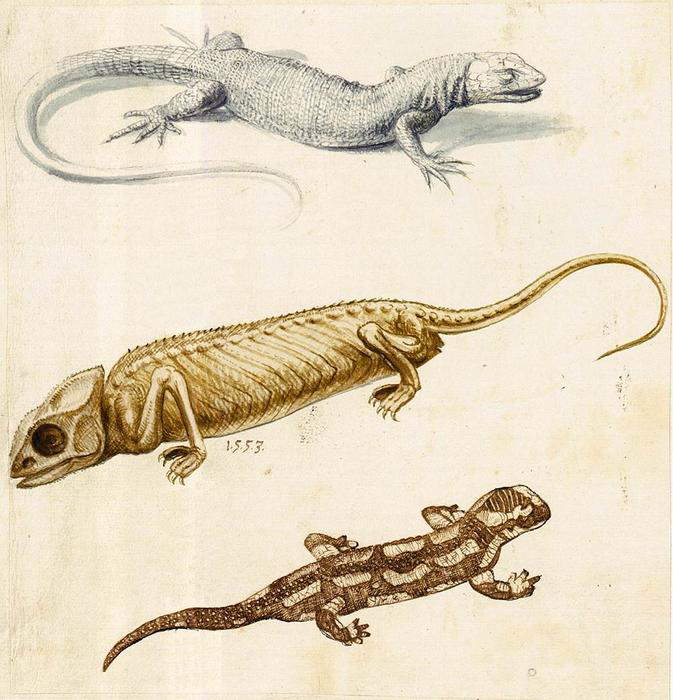

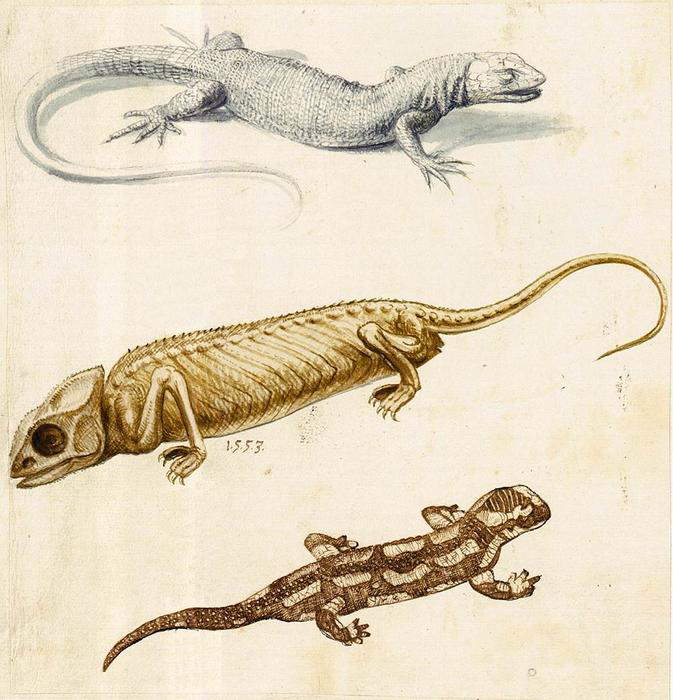

This was the cultural and artistic climate that influenced the production of Giuseppe Arcimboldi (Milan, 1527 - 1593). Already examples of this influence are a sheet dated 1553, therefore made when the artist was still in Milan, where he had reproduced a lizard, a salamander and a dried chameleon, and a tempera panel dated 1562 on which he had depicted a reindeer.

When Arcimboldi was called to Vienna in 1562 by Ferdinand I, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, to become a little later official court portraitist, painter and stager of shows and festivals, he was thus by then a participant in such an artistic vision based on naturalistic studies and direct experience, which he found in full ferment at the Habsburg court: for here, too, men of culture, intellectuals, physicians, botanists, as well as artists were united by their great interest in this field.

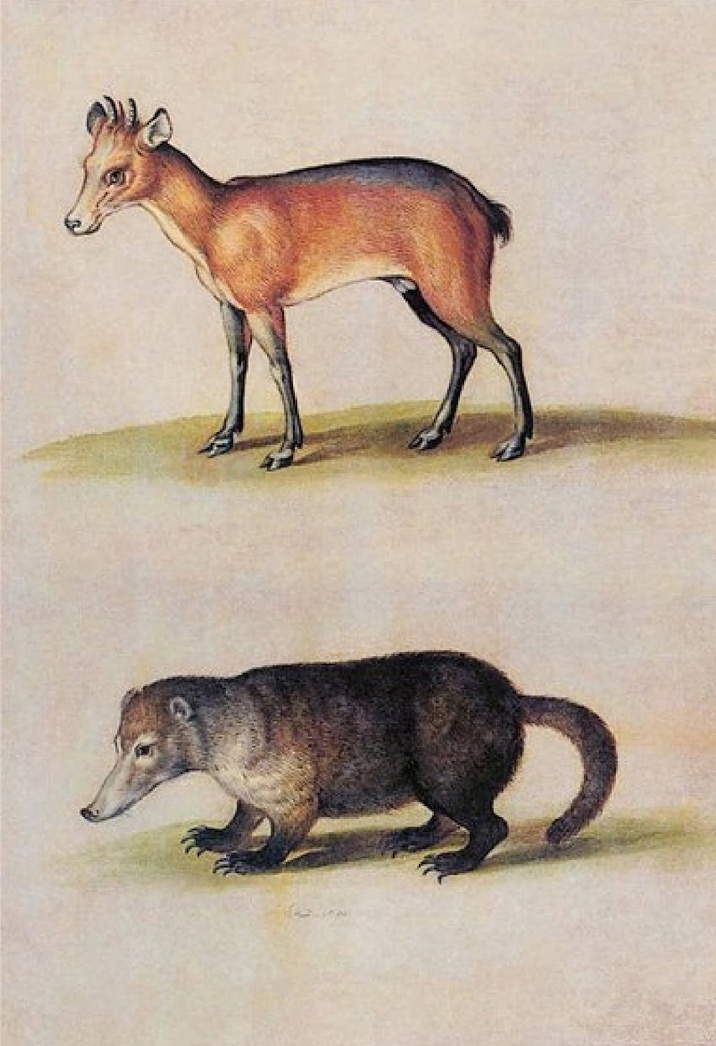

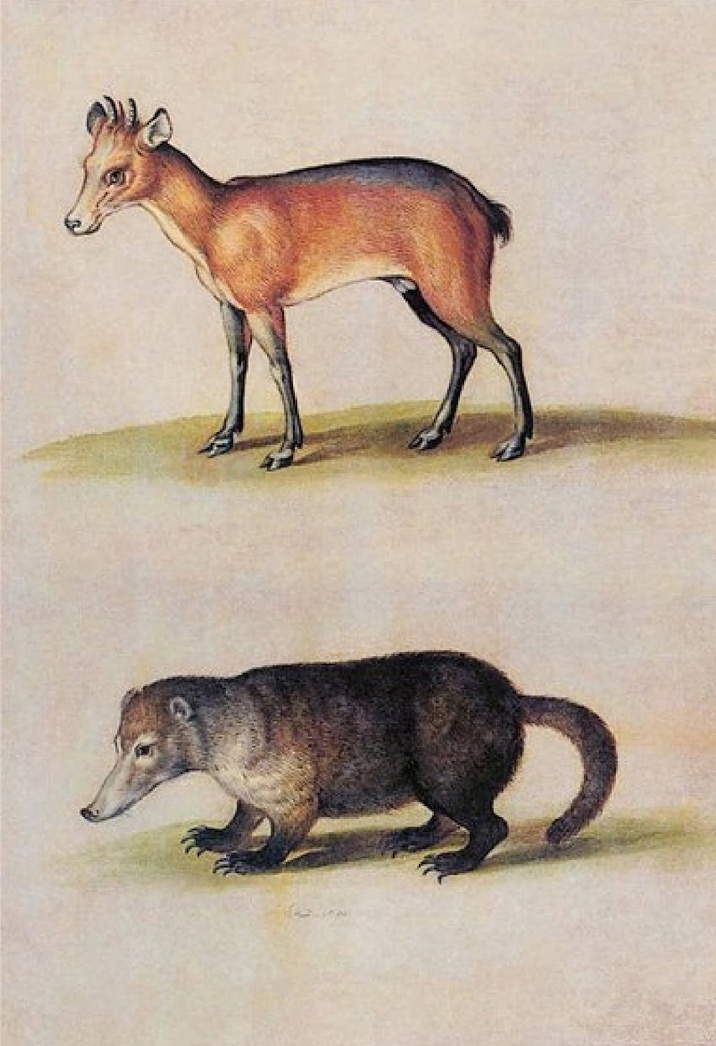

And it was in the Habsburg court, under Maximilian II, eldest son of Ferdinand I, that the artist executed the famous composite heads of the Seasons and Elements series: these are the works that make Arcimboldi an artist creator of oddities. Portraits of faces, usually in profile, that when observed closely reveal their true composition: shrubs, flowers, animals and objects that bound together by genre combine to form a particular and unusual profile. The protagonists of these works are therefore those animals, plants, and flowers that, since his Milanese training, the painter had studied and in which he had also been immersed in Vienna. One of his best-known naturalistic studies dates from 1570, namely the drawing depicting theantelope cervicapra, an animal that also appears in one of the sheets that came to Ulisse Aldovrandi, a Bolognese physician and naturalist who was his contemporary, through Francesco Padovani, a physician at the court of Prague. A sort of indirect collaboration was created between Arcimboldi and Aldovrandi: the latter implemented within his studio and home, in order to pursue his naturalistic research, a veritable museum full of collections consisting of pieces from the animal world, the plant world and the mineral world. A Wunderkammer that could count about twenty-five thousand artifacts from the aforementioned three kingdoms of nature, including eighteen thousand “various natural things” and seven thousand “dried plants in fifteen volumes.” The objects came to him through a dense network of physicians, professors, nobles, and directors of botanical gardens, but in most cases the artifacts belonging to the animal world did not arrive in their entirety, but in fragments or small parts, such as beaks, feathers, horns, teeth and so on. The solution to possessing whole animals, as well as plants and minerals, and especially to enable readers of his writings to see what was being dealt with, was to resort to illustrations made by specialized artists. This included Arcimboldi himself: some of his drawings, as mentioned, came into Aldovrandi’s hands through Francesco Padovani, a physician who was probably a pupil of the latter. Of these only three have survived to the present day, depicting an hartebeest, acervicapra antelope, a reddish cephalofo, a mountain coati and a gerboa, all exotic animals and all replicas of images already executed by the artist. A further influence for the execution of the composite heads came to him from Leonardo: the genius’ works include the grotesque heads, portraits of old men and almost caricatured women usually depicted in profile, which Arcimboldo certainly had well in mind.

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi, Paper Self-Portrait (1575; Graphite and ink on paper, 23.1 × 15.7 cm; Prague, Národnà Galerie) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Study of a Lizard, a Chameleon and a Salamander (1553; watercolor on paper; Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bibl. Cod. min. 42, fol. 128r) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Reindeer (1562; watercolor on paper, 158 x 222 mm; Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, KupferstichKabinett) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Alcephalus and Antelope cervicapra (1584; watercolor on paper; Ms. Aldrovandi, Tavole di Animali, V, c. 20, Bologna, University Library) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Cephalofo and mountain coati (1584; watercolor on paper; Ms. Aldrovandi, Tavole di Animali, VI, c. 87, Bologna, University Library) |

The Seasons and Elements series are characterized by being caught by the viewer as figures in profile, or rather faces, which when viewed from a distance do not appear very unusual in their composition, though somewhat grotesque: the facial features are quite pronounced, almost caricatural. At first glance one notices noses, chins and mouths that we might say do not go unnoticed: one thinks of the long, curved nose, as well as the chin that tends upward, ofWinter kept in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and belonging to the cycle of Seasons made between 1563 and 1566, or of the large nose ofAutumn kept in the Louvre and made in 1573. One certainly cannot help but dwell on the long, pointed chin ofAir, kept in a private collection and part of the cycle of the Elements completed in 1566.

However, these figures in profile, when looked at closely, are of an extraordinary distinctiveness, each time leaving observers glued to the canvases for a long time: the latter will try to recognize each and every element of which the bizarre portrait is composed; they will dig into their naturalistic knowledge to be able to define each and every plant, flower, shrub, animal and object depicted in these paintings, realizing that that very big nose ofAutumn is actually a pear or that the strange pointed chin ofAir is actually the tail of a bird.

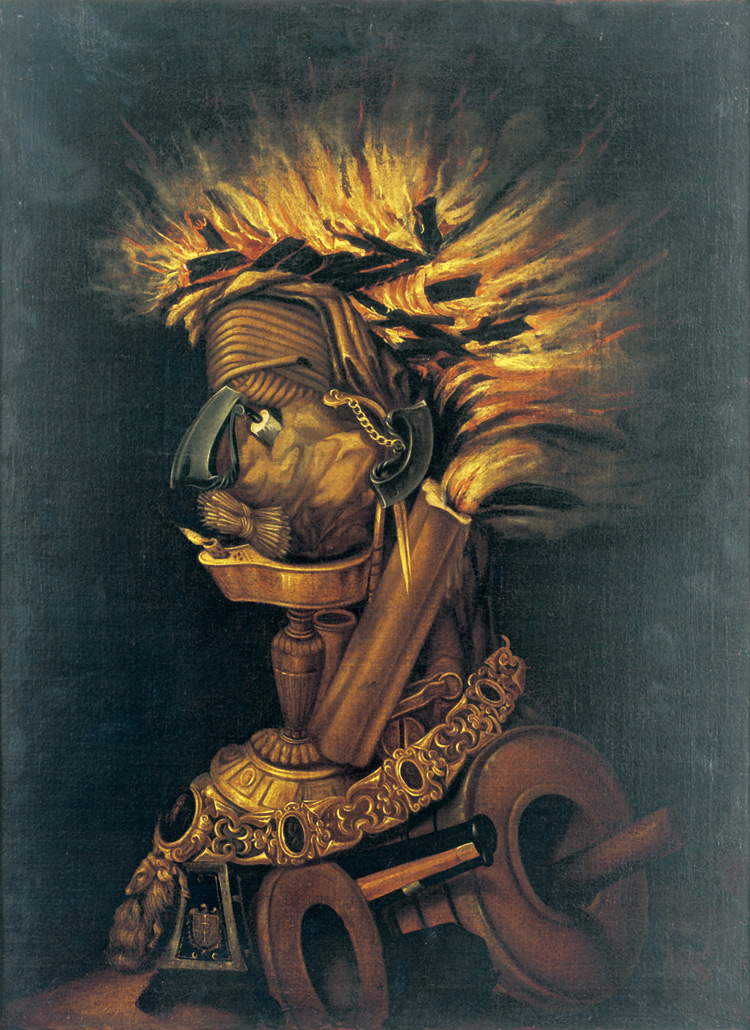

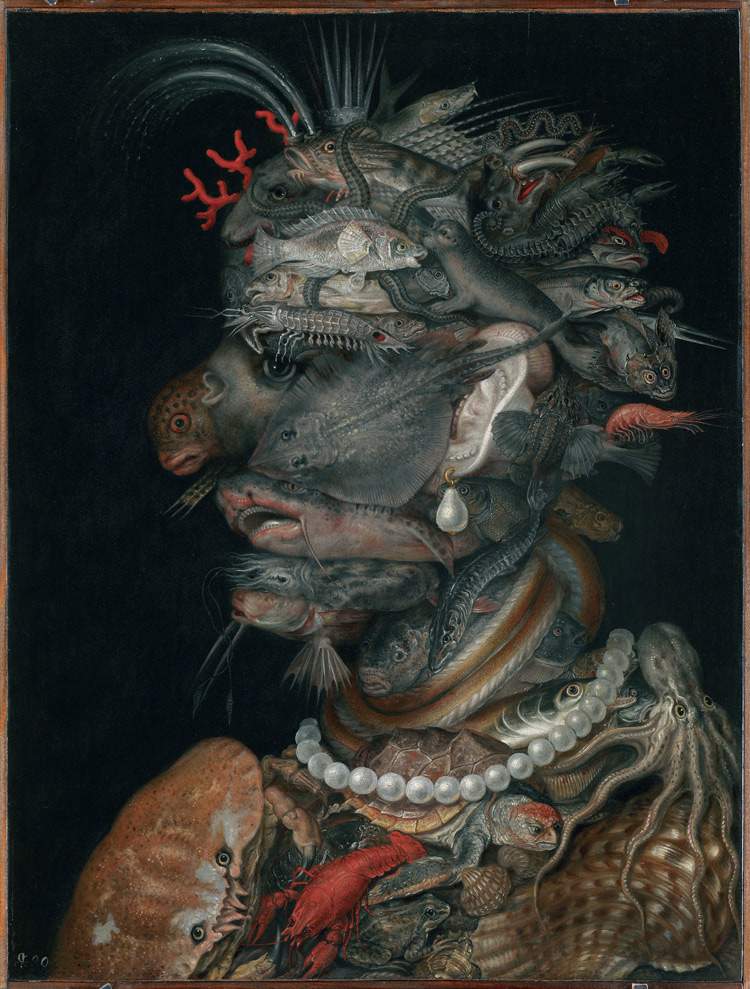

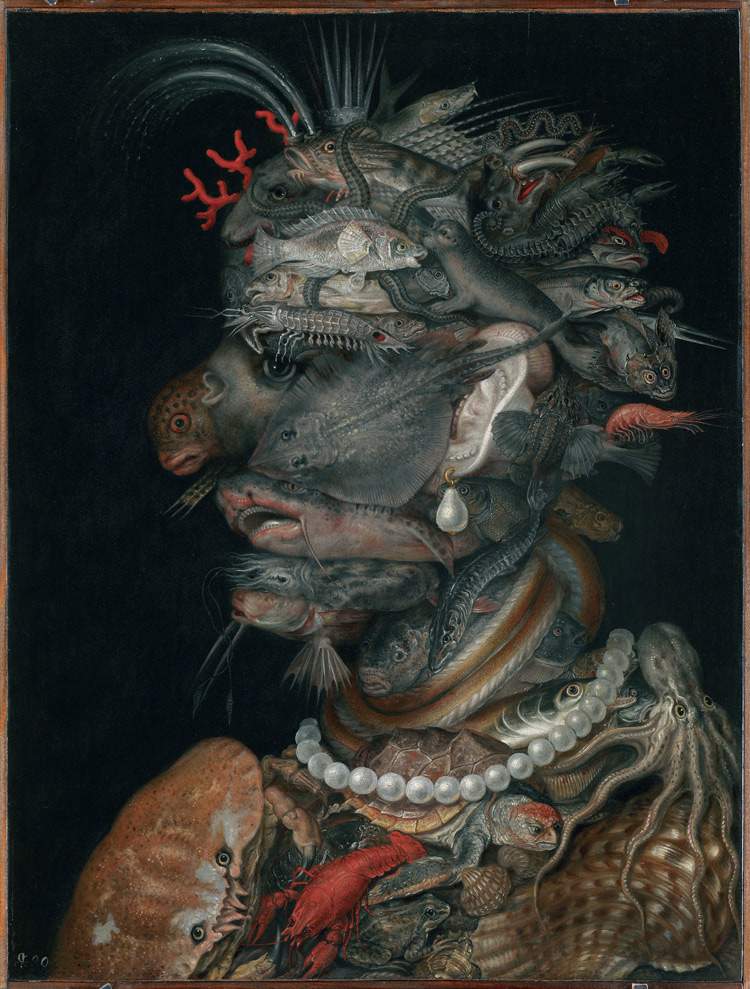

Lots of animal and plant species give life to Arcimboldo’s artistic compositions: flowers and plants for Spring, where a yellow, red, pink, and white blooming mantle represents the rich foliage on his head and a carpet of daisies and other white flowers makes up the collar of his dress; fruits and vegetables forSummer, where his ear is actually a corn cob and where an artichoke sprouts straight out of his wheat dress. Roots and branches forWinter, in which the rather sullen face is accompanied by hair made of ivy branches and a neck that is a tree trunk with a hollow, while grapes, pumpkins and other typically autumn fruits and vegetables make upAutumn, which refers to harvest time; the dress is a wooden barrel. And again: a wide variety of birds form the figure ofAir, in which many little heads with beaks make up the hair of the man portrayed, and the colorful wheel of a peacock adorns his neck and shoulders; in Earth we recognize elephants, sheep, ibex, monkeys, hares, horses and other mammals, all perfectly arranged interlocking with each other. Fish and aquatic animals forWater, embellished with an earring and pearl necklace; burning logs and weapons for Fire.

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Seven Grotesque Heads (c. 1490; Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi, The Spring (c. 1555-1560; oil on panel, 68 × 56.5 cm; Munich, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi, LEstate (1572; oil on canvas, 91.4 × 70.5 cm; Denver Art Museum Collection, bequest from the Helen Dill Fund, inv. 1961.56) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo, THE AUTUMN (1572; oil on canvas, 91.4 × 70.2 cm; Denver Art Museum Collection, bequest from the John Hardy Jones Collection, inv. 2009.729) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi, THE WINTER (1563; oil on linden wood, 66.6 × 50.5 cm; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie, inv. GG 1590) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi (?), LAria (post 1566; oil on canvas, 74 × 55.5 cm; Switzerland, private collection) |

|

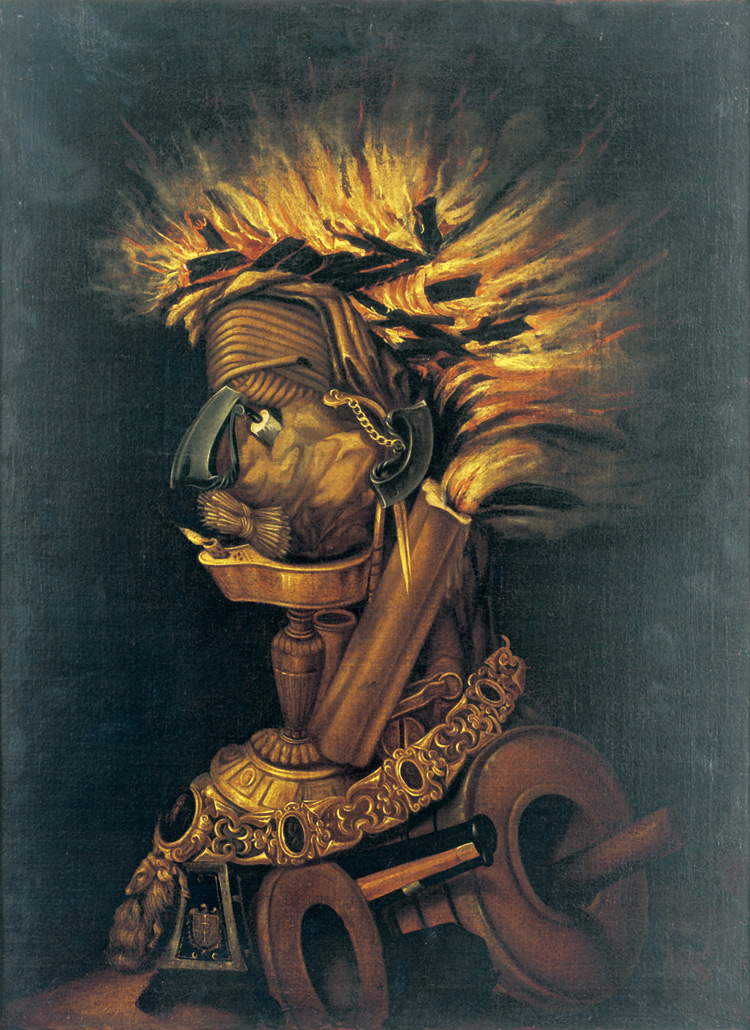

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi (?), The Fire (post 1566; oil on canvas, 74 × 55.5 cm; Switzerland, private collection) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi, The Earth (1566?; oil on panel, 70.2 × 48.7 cm Vienna, Liechtenstein - The Princely Collections, inv. GE2508) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi, THE WATER (1566; oil on alder wood, 66.5 × 50.5 cm; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie, inv. GG 1586) |

The composite heads, to which the Four Seasons and the Four Elements belong, had been called for their strangeness “whimsy,” “jokes,” “crickets,” but analyzed in their complexity they reveal all the culture of that time, a culture steeped in naturalistic studies from life of which Arcimboldi had partaken in his hometown and which he later rediscovered in the course of his existence in Habsburg-dominated Vienna. And also a culture that celebrated the strange and bizarre, leading more and more nobles, intellectuals and men of science to desire them in large numbers in their homes, in their Wunderkammern. In addition to this, it must be considered that these artistic compositions were celebrations of the Habsburg world:Winter depicts the crown and the letter M of Maximilian II sewn on his straw cloak; Fire depicts the double eagle and collar of the Order of the Golden Fleece, an order founded by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy and ancestor of the Habsburgs; andAir depicts the Habsburg eagle and peacock.

Although the greatest homage to the Habsburg house he paid was with an entire work, Vertumno, an imposing portrait made in about 1590 and now preserved in Skokloster Castle in Bålsta, Sweden, which depicts, this time in a frontal and not a profile position, the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, son of Maximilian II. Grapes, melons, peaches, cherries, ears of corn, flowers and other natural elements make up the god of seasons and metamorphoses; the lush production of fruits and flowers typical of different seasons and from different areas of the world celebrate the Habsburgs as a kingdom of infinite prosperity and well-being.

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi, Vertumno (1590; oil on panel, 70 x 58 cm; Bålsta, Skokloster Castle) |

The humanist Gregorio Comanini (Mantua, c. 1550 - Gubbio, 1608) even composed a sonnet about this last work by Arcimboldi, published posthumously in 1609 in his Canzoniere spirituale, morale e d’onore. The sonnet reads, “Qual tu sii, che me guardi / strana, e difforme immago, / e ’l riso hai su le labbra, / che lampeggia per gli occhi, / e tutto ’l volto imprime / di novella allegrezza, /al veder novo monstro, / che Vertumno chiamaro, / neè l’loro carmi, gli antichi / dotti figli d’Apollo; [...] Tempo fu, che confuso / era ’n sé il mondo: / however, that ’l ciel col fuoco, / e ’l fuoco, e ’l ciel con l’aria / eran mescolati, e l’onda/ con l’aria e con la terra, / e col fuoco , e col cielo: / e senz’ordine il tutto / stavasi informe, e brutto.” Confirmed here is the beauty of ugly things, the admiration for ugliness, in line with the culture contemporary to the author of Composite Heads. Arcimboldi was a great artist who was able to capture the salient features of his era and introduce them into his art, in an extravagant way; his bizarre works will forever remain recognizable to all, born of an exceptional personality.

Reference bibliography

- Sylvia Ferino-Pagden (ed.), Arcimboldo, exhibition catalog (Rome, Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica di Palazzo Barberini, October 20, 2017 to February 11, 2018), Skira, 2017

- Michele Proclamato, Giuseppe Arcimboldo: the alchemical painting of immortality, Lindau Editions, 2015

- Werner Kriegeskorte, Arcimboldo, Taschen, 2000

- Norbert Schneider, The Portrait, Taschen, 2002

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.