From Mount Fuji to Mount Etna and Mount Vesuvius: a history of geological art

“We belong to something beautiful,” promise the billboards for a multinational cosmetics company. Instead, according to Kant, it is beauty that is inherent in us, and intelligible only through the lens of feelings. The basis of modern thought lies between reason and feelings, between Enlightenment and Romanticism, from Nietzsche’s 1870 dialectic between Apollonian and Dionysian to the discovery of cooperation in the human brain between the cortex and limbic system. Beauty in philosophy combined with the Good and the True are the transcendental (that is, beyond empirical reality and our cognitive limits) universal values of being. In short, beauty is there, affects and impacts us even when it is not valued. But without a culture apt to process and elaborate its astonishment, beauty remains for all intents and purposes a psychoactive substance, acting on our already highly addicted minds of users and consumers like a narcotic.

Culture is a necessary regulation, not only of our social life but also of our brain functions. Today, in the impasse of a society deculturized by consumerism, it is as if we are all a bit like stoned people at the mercy of the side effects of being, hyper-existentialists.

Almost at the same latitude, like a ten-thousand-kilometer-long trait d’union of the Eurasian plate, we have two major symbols of East and West even more than the Himalayan and Mont Blanc mountain ranges: the Fuji and Etna volcanoes that became World Heritage Sites in the same year in 2013, just over a decade ago. Both more than three thousand meters high, although erected at antipodes and active in different ways the two volcanoes have the same effect on our minds, whether we glimpse them from the provinces of Tokyo or Catania: the grandeur, the majesty of their conical and iconic form provokes instant ecstasy and epiphanies, enraptures and compels us, better than any absolutism, government or shrine, to reverence, contemplation and recollection against all mass tourism, ski facilities and other consumerist drifts.

![Katsushika Hokusai, Clear Day with a South Wind [Red Fuji] (Gaifu kaisei), from the series Katsushika Hokusai, Clear Day with a South Wind [Red Fuji] (Gaifu kaisei), from the series](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2025/2987/hokusai-fuji-rosso.jpg)

Volcanoes are, when active and mostly above crowded cities, the most potent manifestation of Life with a capital letter on our planet, like beating aortas over a beating heart (the core at the center of the earth probably radioactive) and together the consciousness that Earth, not just us, is living.

We all “inhabit,” like bacteria, a giant that is planet Earth in constant movement and transformation ; there is this underlying awareness in the awe that seizes us at the sight already in the distance of the top of a great volcano, when snow-capped, shrouded or framed by suggestive atmospheric conditions, rays and mists, sunrises and threats of eruptions. All the science in the world is not enough to extinguish this prevalence of the mythological in Creation. At the first natural panorama, especially far from cities and our other forms of settlement, animism prevails and secularism lapses, we are inevitably overwhelmed by the sacred and all affected by mysticism.

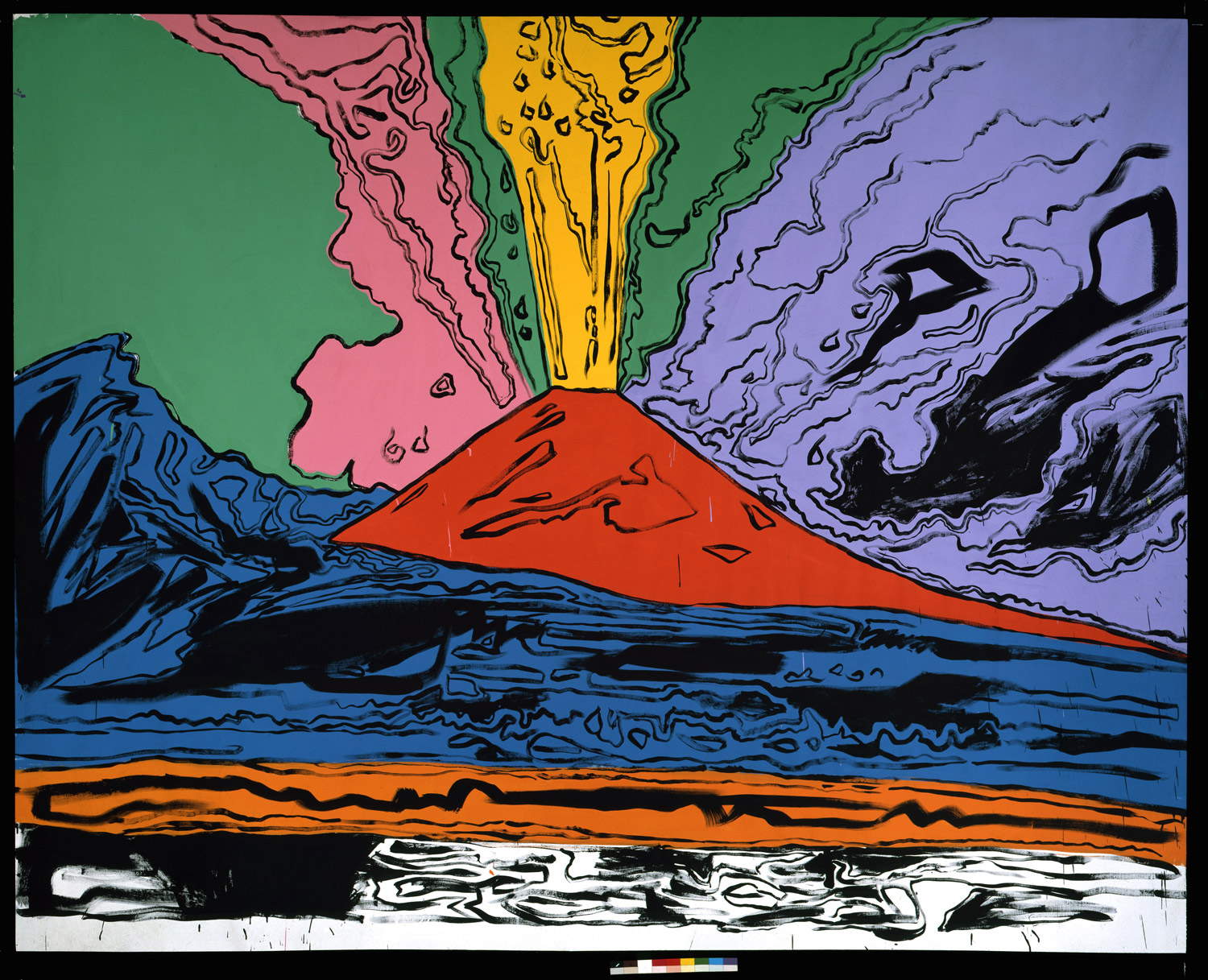

Hokusai and Hiroshige, and a century later their American descendant Warhol, were able to draw from the universal volcanological awe the fundamentals and make of it a graphic format, a new aesthetic canon, far beyond the vedutista genre from Vanvitelli to Canaletto between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, which conquered the world and marked the beginning of the avant-garde and contemporary art in the West.

Until Master Hokusai’s Great Wave, part of his masterful 1830 xylographic series of 36 Views of Mount Fuji, which later became the most famous of the ukiyo-e (art prints of the Edo period, literally “pictures of the floating world”), Japan had been a Sakoku, an autarky, hermetic and impervious to outside influences, Christianity and the early industrial revolution, for two and a half centuries. Signed in 1854 at the Kanagawa Convention under American pressure, the first Japanese prints landed in Europe via the Dutch Navy administration at Nagasaki harbor and ended up shaking European academisms. The prints are collected, emulated, studied by writers such as the Goncourt brothers, and finally decoded into the realism of Courbet, by Manet, and by the nascent Impressionists in France, Degas, Monet, Renoir, Pissaro, and then Gauguin, Van Gogh, and Toulouse-Lautrec, giving rise to Japaneseism, the underlying thread of nineteenth-century avant-gardism.

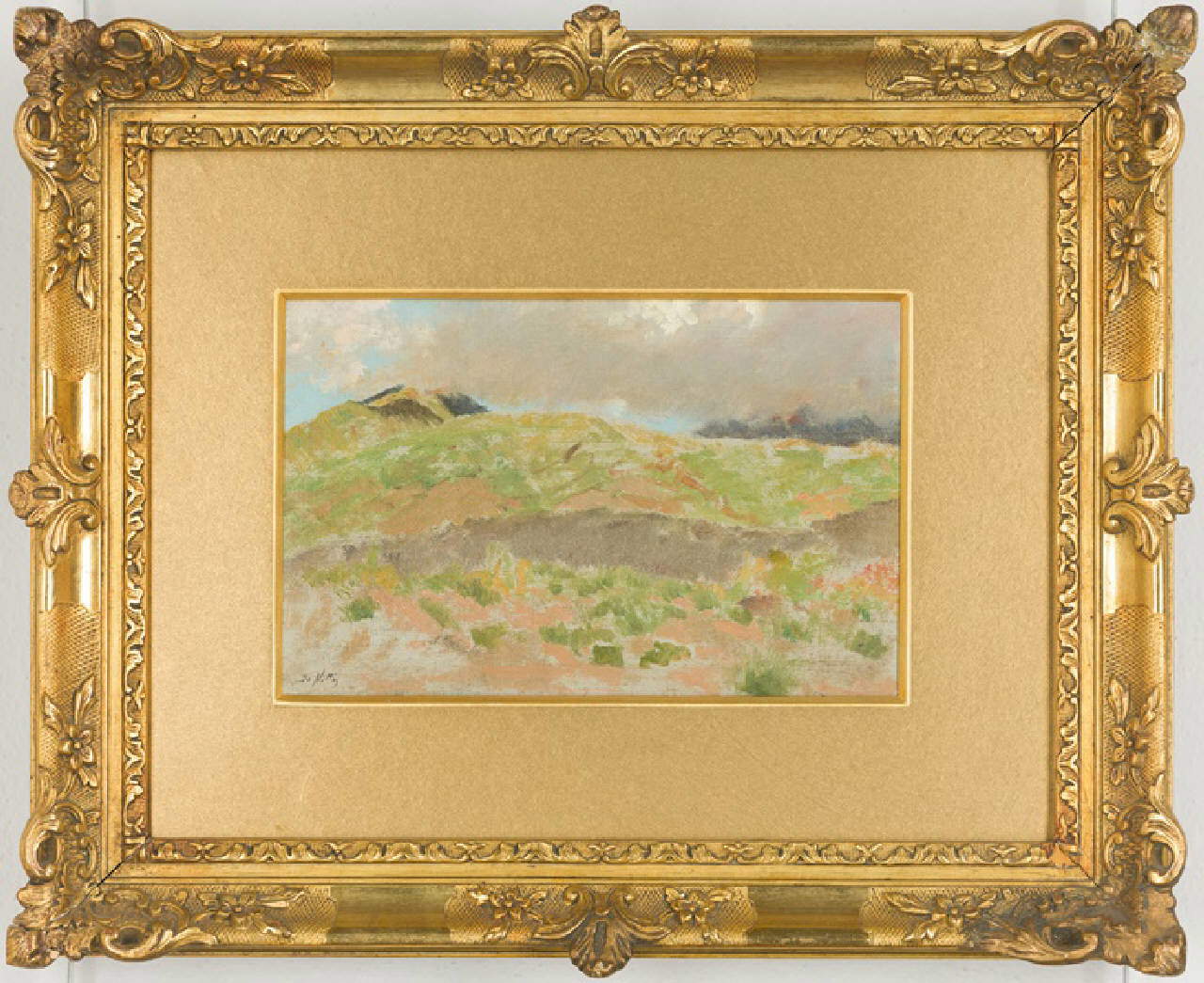

Among the leading exponents of the first private group exhibition in History opened to the public in 1874 in Nadar’s photographic studios, the Italian De Nittis had returned to Naples, fleeing momentarily from Paris during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. And it was precisely during this interlude in Naples that De Nittis had the insight to reread the Japanese format in a Campania sauce, consigning to History his 12 oils On the slopes of Vesuvius, a high point of Impressionism for the dazzling presence and mutability of the erupting volcano, superior therefore on the level of instantaneousness and variation, to the other equally monumental but static subject chosen by Monet, namely the series of thirty oils of Rouen Cathedral.

A century later, American Andy Warhol could not fail to include this format that has become traditional in the Olympus of Pop Art, with his Vesuvius, a 1985 series of 17 silkscreens dedicated to the volcano that is the symbol of Naples and the result of his meeting with gallery owner Lucio Amelio. How much of a revolutionary gift does Italy give to global Art History with its proper balance between a living and powerful nature and that crossroads of cultures and civilizations in which everyone recognizes themselves?

Although geologists ascertain to us that they are autonomous and that there are no lava conduits linking the world’s volcanoes together, we do know, however, that they all arise where the major tectonic plates of the planet meet and collide, as if they were these volcanic edifices or eruptive centers, as they are scientifically called, primordial manifestations of our true frontiers, natural anti-cities and indicators of where paradoxically we should never have built or settled.

European politically but geologically already somewhat American, off Greenland Iceland is the only country in the world that is an entirely volcanic island (rapidly expanding, by the way), and one of the rare higher emerged parts of the mid-Atlantic ridge. Iceland is literally split in two; it is the country where one can see for oneself the fracture and separation between the North American and Eurasian plates, a perfect metaphor for certain forcings of the Atlantic Pact. On the other hand, the so-called Ring of Fire, of which Fuji is just one of many hot spots, is the other side where the two plates border the Pacific.

Told from a geological point of view, the history of contemporary art so far is the child of the Eurasian clash with the African plate and the North American plate. Who knows, maybe continental volcanoes are the places from which we should reasonably discuss and place our true geopolitical boundaries today.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.