Louis Aimé Aldolphe Jules Breton, French painter and poet, was born in Courrières, a small town in the Pas de Calais department in the Haute-France region, on May 1, 1827. His early studies were at the College of Saint Bertin in Saint Omer and later at the Royal College of Douai. In 1843 he moved to Ghent to attend the Royal Academy under Félix de Vigne, and in 1858 he married the latter’s daughter, Élodie; from their marriage was born Virginie, the couple’s only daughter, also a painter. In 1846 he worked briefly at the Antwerp Academy. The following year he was admitted to the École des Beaux Arts in Paris, where he took courses from Michel Martin Drolling. However, despite his academic teachings, travels to major European cities, and multiple honors, Jules Breton is nostalgic for his native land, as well as being intimately drawn to life in the fields.

In his autobiography La vie d’un artiste: Art et Nature he writes: “Sorti du tourbillon parisien, à chaque retour à Courrières, je ressentais l’immense volupté du grand calme champêtre et des promenades solitaires où l’on peut suivre les effets de la Nature, en étudier les causes sur des motifs simples et d’où ressort d’autant mieux l’évidence des grands lois éternelles. Alors me revenaient les milles problèmes discutés à Paris entre camarades. Ils se redressaient, dans l’isolement, devant ma raison; je cherchais à les résoudre. Peut être aurais je mieux fait d’aller droit devant moi sans autre souci que de satisfaire la sorte d’idéal que je ressentais, sans excitation vane, sans ambition trop élévée. C’est ce que j’avais fait sans m’en douter lors de mes pemieres tableaux de Courrières; c’est ce que je tâche de faire, moins inconsciemment, à présent... . J’ai toujours cru que le but de l’Art était de réaliser l’expression du Beau. Je crois au Beau, je le sens, je le vois! Si l’homme chez moi est souvent pessimiste, l’ar tiste, au contraire, est éminemment optimiste” (“Coming out of the whirlwind of Paris, every time I returned to Courrières, I felt the immense voluptuousness of the great rustic, quiet and solitary walks where one can follow the effects of Nature, study its causes on a simple basis and from which the evidence of the great eternal laws emerges all the better. Then I was reminded of the thousand problems discussed in Paris among the comrades. They stood up, isolated, before my reason; I was trying to solve them. Perhaps I would have done better to go straight without other worries than to satisfy the kind of ideal I felt, without vain excitement, without too much ambition. This was what I had done without suspecting it during my first Courrières paintings; it is what I try to do, less unconsciously, now.... . I have always believed that the purpose of Art was to achieve the expression of Beauty. I believe in Beauty, I feel it, I see it! If the man in me is often pessimistic, the artist, on the contrary, is eminently optimistic.”).

Breton, also known as the painter of peasant life, is considered one of the major representatives of Rural Realism, an artistic current that arose in France around the middle of the 19th century which, in contrast to the spiritualistic tendencies of Romanticism, rejects any imaginative idealization, depriving it of careful observation and representation of both nature and reality. Generally speaking, however, the figures painted by Breton are idealized, have no physical defects, and do not appear worn out by labor or time. On the contrary, in his works, the French painter presents an almost idyllic vision of rural existence as he believed that “le but de l’Art était de réaliser l’expression du Beau.” Breton’s poetic depictions of graceful peasant women, often modèles paysannes, which he favored for their authenticity over professional models against the backdrop of the Upper French countryside, were a great success not only in France but also in England and the United States, and because of this great popularity, numerous engravings and prints were made that contributed to the popularity of Breton’s works.

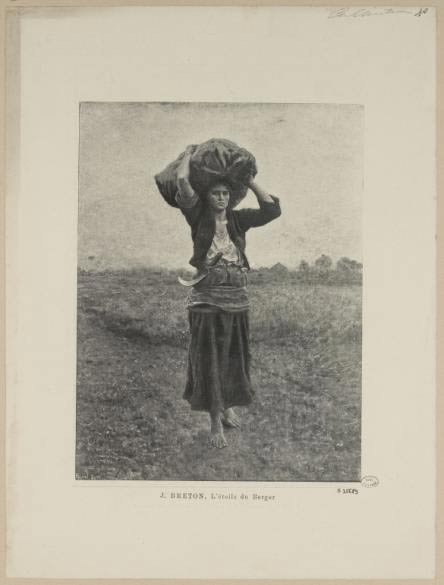

In 1887 Jules Breton paintedÉtoile du Berger (Fig.1) (oil on canvas, 102.8x78.7 cm) in which the painter depicts a young peasant woman with a proud look, as she returns barefoot from the fields carrying on her head a sack with the day’s harvest: it is twilight, the moment when Capella, one of the brightest stars in the firmament, begins to rise behind the woman who, in her elegant and majestic appearance, is more reminiscent of an ancient dogwoman than a peasant woman. It is the hour of silence and serene illusion that the French artist depicts in his work imbued with realism and melancholy.

Étoile du Berger was first exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1888, considered the most important art event not only in France but throughout Europe. Writer and literary critic Henry Houssaye writes about the paysanne exhibited by Breton at the Paris Salon, “M. Jules Breton expose un autre tableau: l’Étoile du Berger. L’orbe sanglant du soleil descend à l’horizon, tandis que dans le ciel qui s’obscurit apparâit la première étoile. Une grande et robuste paysanne, sa journèe de travail accomplie, rentre au village en portant sur ses épaules, accoutumées aux lourds fardeaux, un gros sac de pommes de terres.. mais imaginez qu’elle porte sur le dos une gerbe de blé au lieu d’un sac de pommes de terre, et elle pourrait être aussi la personification de la moisson. C’est une Cérès moderne” (“Mr. Jules Breton exhibits another painting: the Étoile du Berger. The bloody globe of the sun descends to the horizon, while in the darkening sky the first star appears. A tall, sturdy peasant woman, having finished her day’s work, returns to the village carrying on her shoulders, accustomed to heavy loads, a large sack of potatoes ... but imagine that she is carrying a sheaf of wheat on her back instead of a sack of potatoes, and she might as well be the personification of the harvest. She is a modern Ceres.”) The French poet and chronicler Firmin Javel in the weekly “L’Art français” describes Étoile du Berger as an exquisite page created in Courrières’ atelier and in which the artist depicts the solemn figure of the peasant woman completely enveloped by the infinite poetry of the evening, by the intense lyricism characterizing the paintings of the poet-painter Breton. Also in 1888, the artist Alfredo Müller (Livorno, 1869 - Paris, 1939), who had recently moved with his family from Italy to Paris, executed an etching reproducing Jules Breton’s work that was published in Arts and Letters, An illustrated review.

A reproduction of Jules Breton’s painting is kept at the Musée Carnavalet, the museum dedicated to the life and history of Paris. How and when the graphic work came to be part of the Parisian museum collection is not documented, but its existence is further evidence of the great notoriety and diffusion of the Courrières painter’s a rtistic output. Within a short time Breton’s painting became known and appreciated not only in Europe but also in America. Favorable criticisms appeared in specialized magazines such as The Connoisseur: in one of his articles, Eugen von Jagow points out how American art lovers were willing to pay even very high sums of money in order to come into possession of a work by Breton. In 1889,Étoile du Berger was presented at the Universal Exhibition in Paris, where numerous engravings and prints of the work in question autographed by Breton himself were already available. Already in the same year the painting was acquired and exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago where it remained until 1908, after which it was purchased by philanthropist and art collector Arthur J. Secor.

Jules Breton died in Paris on July 5, 1906. Six years after his death, in 1912, at the inaugural exhibition of the Toledo Museum of Art (TMA), a world-renowned museum located in the Old West End neighborhood of the city of Toledo (Ohio, U.S.),Étoile du Berger, whose title is translated to The Sheperd’s Star, was loaned for the inaugural event by Arthur J. Secor (then second vice president of the Toledo Museum), who in 1922 donated the work to the Toledo Museum, an institution at which it has been on display in Room 32 ever since.

Raffaele Oronzio Maccagnani, older brother of Eugenio (Lecce, 1852 - Rome, 1930), an internationally renowned sculptor, was born in Lecce on March 24, 1841, to Mattia Maccagnani and Rosa Grassi. His paternal family was originally from Lizzanello, a small town on the outskirts of Lecce, famous for being the birthplace of the illustrious scientist Cosimo De Giorgi (Lizzanello, 1842 - Lecce, 1922). In the Salentine capital, Mattia is known as a renowned goldsmith and jeweler, while his brother Antonio (Lecce, 1807 - 1889) is a “celebrated statuary of saints in papier-mâché”; his mother Rosa is the daughter of Pasquale Grassi (Campi Salentina, 1781 - Lecce, 1817) and sister of Giovanni (Lecce, 1809 - 1882), both rather highly regarded painters in the Salento area. Raffaele was thus raised by a family of artists with a varied education and grew up in an environment rich in creative solicitations and stimuli without, however, ever managing to achieve the notoriety of his brother Eugenio. Raffaele learned the first rudiments of art in Lecce, first in the workshop of his paternal uncle Antonio and then from his maternal uncle Giovanni. After his first teachings in his hometown, in 1865 he obtained an economic contribution from the Provincial Council of Terra d’Otranto that allowed him to move to Naples. Here he frequented the atelier of painter Vincenzo Petrocelli (Cervaro, 1823 - Naples, 1896) and the studio of Domenico Morelli (Naples, 1826 - 1901), a leading figure in Neapolitan figurative culture in the second half of the 19th century, thanks to whom Raffaele perfected the technique of drawing and painting, as witnessed in a letter written in 1906 by his brother Eugenio to Onorato Roux: “At this time, my brother Raffaele, studied painting in the house of another uncle of mine, Giovanni Grassi, a painter. After a few years, my father sent him to Naples, to perfect himself, under the direction of Domenico Morelli. After some time had passed, Raffaele, to justify to my Father the fruit of his studies, sent several works both in oil painting and sfumino.”

Supporting a son away from home is extremely demanding for Mattia, father of five other children: young Raffaele therefore proceeded in his artistic studies with assiduous commitment and aware of the economic efforts the family endured to keep him far from Lecce. In 1868 Raffaele Maccagnani painted Lo Zingaro pittore napolitano (inspired by an episode between myth and legend concerning the life of the painter Antonio Solar io detto lo Zingaro) and sent it to the Società Promotrice delle Belle Arti di Napoli, an association founded in 1862 on the example of the Florentine and Turin promotrici, whose aim was to promote art and artists of the moment. The judging committee decides to admit the work to the exhibition. The news is immediately spread with enthusiasm by the Lecce newspapers: “With pleasure we announce that the young painter Raffaele Maccagnani, our fellow citizen sent a painting in oil representing the Gypsy, to the Society Promotrice delle belle arti, and the Jury admitted it, and now it is placed in the third room of the Exposition just opened in Naples. It would be desirable that this young man, who gives such good hopes in art, be counted among those, toward whom the Province is wide of subsidies and encouragement.” “On the painting of our fellow citizen Raffaele Maccagnani, which we mentioned in the previous issue, we found the following mention in the newspaper of Rome, of the current 14th. This Gypsy is represented at the moment that he is eavesdropping at the door of splendid hall, in order to feel the effect that his picture produces in the eyes of Colantonio del Fiore, the desired inventor of oil painting, and a man whose daughter loved the Gypsy passionately, so that from a blacksmith he mutated into an artist. This little picture, in its noble vulgarity, is well thought out, well composed, and the curiosity that moves the Gypsy also moves the viewer to question its subject. It is a little picture that stands by itself full of color, with be’ contrasts, and worthy of praise pere the choice of the subiect, and for the happy success of the concept.”

The articles that appeared in the newspapers and the favorable criticism seemed to mark the beginning of a promising career for the young artist, except that the work in question quickly caused a great stir, as it was judged to be a copy of a sketch by Domenico Morelli, Raffaele Maccagnani’s master during his stay in Naples. On this subject, writer and critic Vittorio Imbriani writes: "Raffaele Maccagnani, another pupil of Petruccelli, probably unconscious of the imitation, for he will hardly have seen with his own eyes the commendatore’s stain, availed himself of it for a small picture entitled the Gypsy. Unwittingly to take a subject and the way of seeing it from Morelli, is easier than to usurp his execution: but no doubt he will filth this subject fifteen years hence, as he would filth a morsel premasticated by others; nor of a mediocre little work by Maccagnani can, in spite of the suggestions of his master, make up for a work by Morelli." In 1886 the Neapolitan painter Zingaro was presented at the Promotrice in Naples, where it was a considerable success (it would be purchased by Duke Amedeo d’Aosta).

Raffaele Maccagnani again participated in the Naples Promotrice in 1869 and exhibited Dante and the Blacksmith. The painting “depicts Dante when one day, hearing his verses being crippled by a blacksmith singing them, he goes to the blacksmith’s workshop and turns his tools upside down, telling him you spoil my things, I spoil yours.” In the spring of 1870 he presented another painting, La Vanitosa. The two works were a significant success and both sold. Suddenly the young artist is forced to leave the Neapolitan city forever and return to Lecce, giving up part of his aspirations for growth and education. In June 1870, Raffaele’s father died, leaving his wife and children in a precarious economic situation. Raphael was 29 years old and as the eldest son it fell to him to provide for the family’s material needs. As early as October of that year, advertisements appeared in local newspapers advertising private drawing lessons given by Raffaele at his home in Largo San Vito in Lecce.

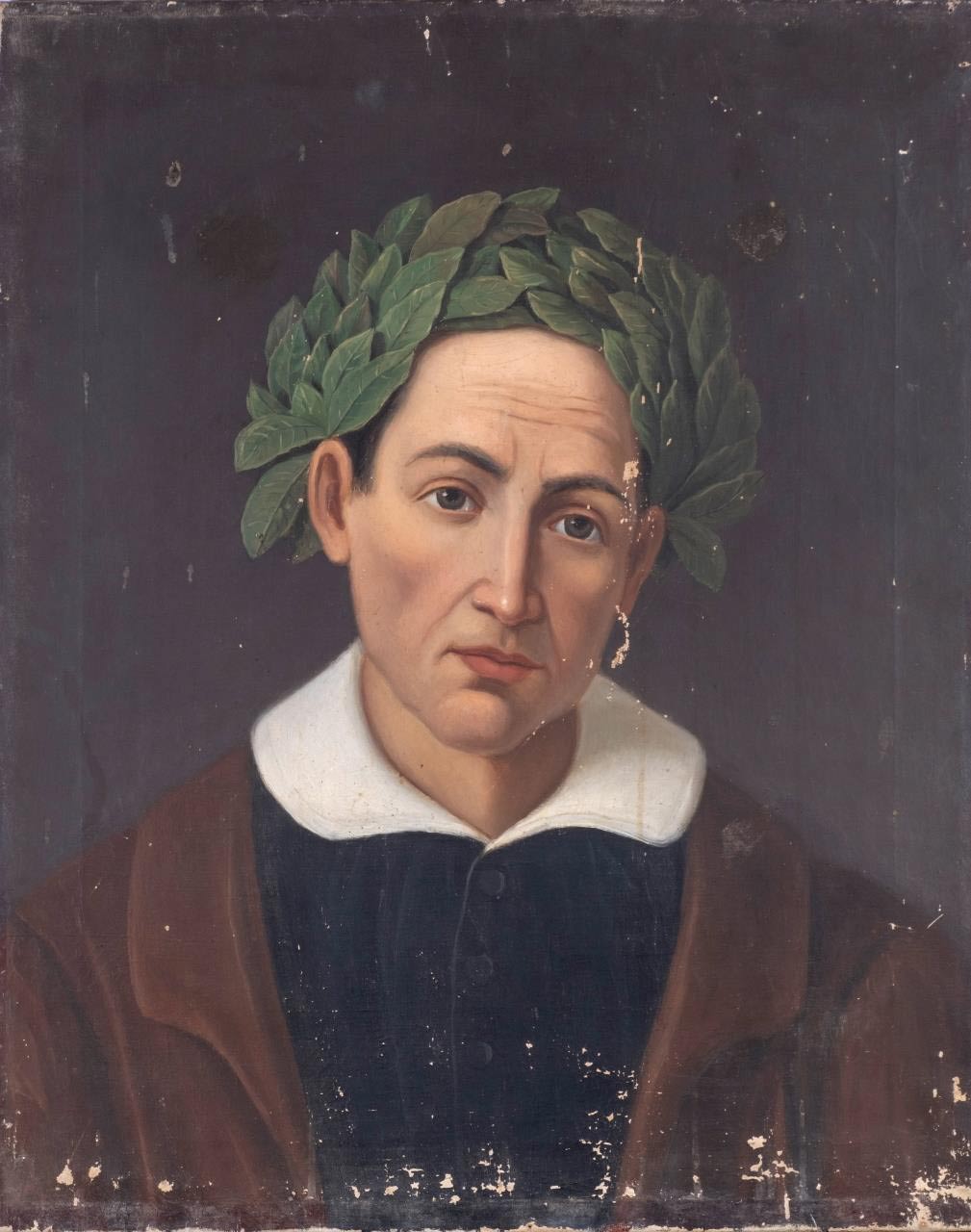

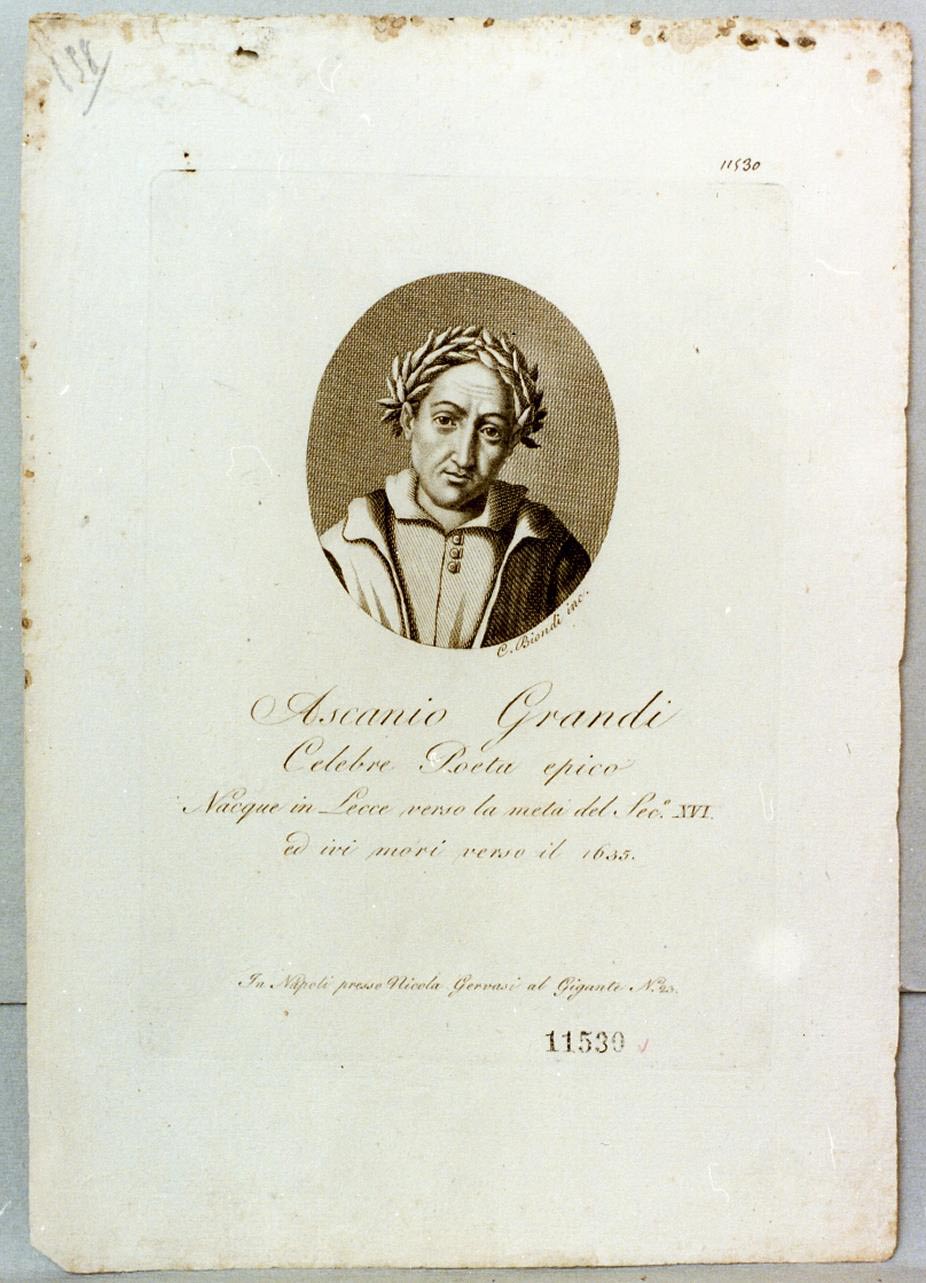

A discreet and reserved man, Raffaele did not like his political ideas or sympathies to be in the public domain. In the fall of 1874, after reading in the pages of the Gazzetta di Terra d’Otranto of his intention to join the Southern Unitarian Association, he firmly requested that this rumor be denied in a letter addressed to the editor of the Propugnatore, “I did not make any dimanda of a similar nature, nor did I ever have in mind to belong to such an association. As a gentleman and artist I am the friend of all; as a politician let me be left alone with my sacred opinions.” In 1879 he was entrusted with the teaching of drawing at the Giuseppe Giusti Association of Lecce progress association is founded in 1875 whose primary social mission is to “promote and disseminate popular education” and of which Michele Astuti and Cosimo De Giorgi, among others, are members. In 1897 following the dissolution of the association due to the lack of economic resources, the members decided to donate to the Provincial Administration five hundred volumes from its library as well as a pair of portraits signed by Raffaele Maccagnani, namely two oil paintings, one depicting Giuseppe Libertini and the other Ascanio Grandi.

In the storerooms of the Sigismondo Castromediano Museum in Lecce there is a painting depicting the illustrious epic poet from Lecce, a work so far unattributed. I believe I can state that the above-mentioned work can be attributed to Raffaele Maccagnani who has, in all probability, taken inspiration from the etching executed by Carlo Biondi, an engraver active in Naples in the first half of the 19th century.

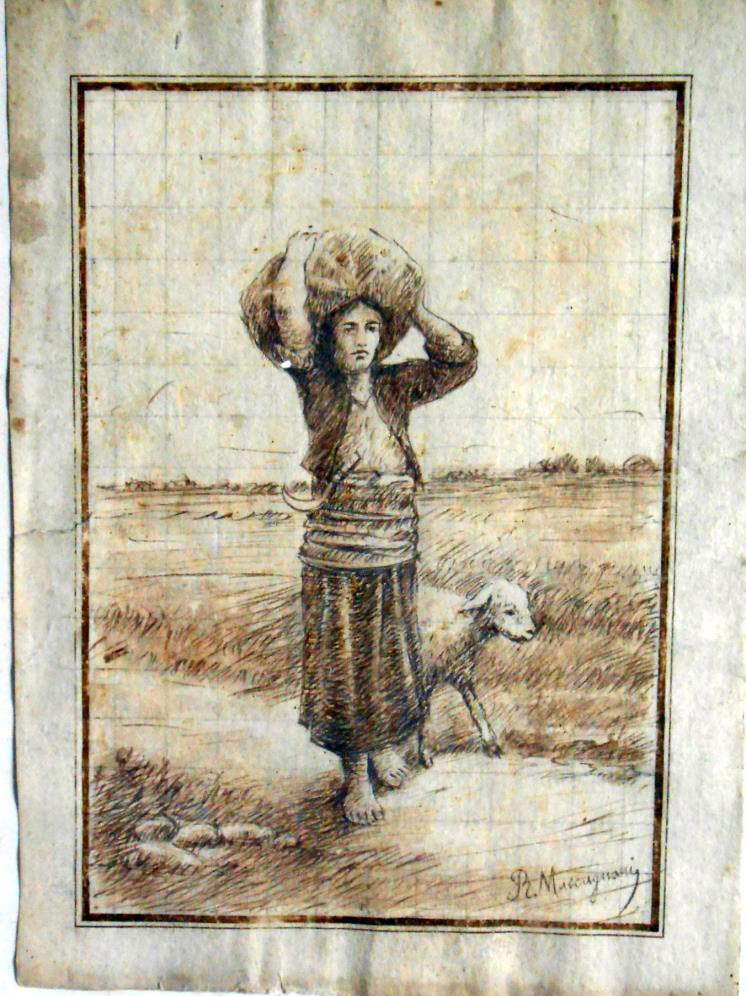

On May 29, 1880 Raffaele was united in marriage with Maria Concetta Cesani and soon the family expanded with the birth of several children. In 1881 he designed the new uniforms for the Banda Cittadina di Lecce: the uniforms, in blue black with light blue hems and bands and silver frises, were made by the Società Operaia dei Sarti and worn for the first time during the celebrations in honor of St. Oronzo, patron saint of the Salento capital. Starting in 1884 he received a teaching position at the School of Drawing of the City of Lecce, where he was called to replace the Lecce painter Vincenzo Conte (Lecce, 1834 - 1884), who died prematurely. Parallel to his teaching activities, Raffaele continued to devote himself to the execution of several paintings for public and ecclesiastical commissions: Our Lady of Rest and Our Lady of Sorrows (1879), The Fool and the Drunkard (1881), the portrait of Colonel Luigi Scarambone 1882), portraits of Giovan Battista Libertini and Raphael d’Harps (1893), Santa Rita da Cascia (1910), the Coro campagnolo and the portraits of Oronzio and Giuseppe Carlino (1913), Il bacio di San Giovanni a Gesù, Donna che raccoglie il cotone, portraits of illustrious Salento personalities including Antonio Panzera, Antonio Guariglia , Giuseppe Marangio. In the course of his painting career, certainly post 1888, Raffaele Maccagnani painted the Shepherdess, a work in which he depicts a young woman as she advances on a dirt road with her harvest wrapped in a handkerchief and resting on her head. The girl’s expression is resigned, her face tried by fatigue as well as her bare feet i nduritized by hours of hard work. The clothing is poor and essential; the accompanying sheep seems to represent the only company and comfort for the girl in the deserted and silent countryside. The full-bodied, almost rough brushstrokes ste if by the painter on the canvas also contribute to making the work even more charged with raw realism.

Raffaele Maccagnani was evidently fascinated by Breton’sÉtoile du Berger, so fascinated that he decided to copy the work. We have no certainty as to when he had occasion to become acquainted with the French artist’s painting, but we recall that frequent trips were made by his brother Eugenio to Paris to participate in international exhibitions and shows. In 1889, the year in whichÉtoile du Berger is exhibited at the Universal Exhibition in Paris, Eugenio Maccagnani participates in the same event and is awarded the gold medal for his work The Gladiators: it is probably thanks to his brother the sculptor, who often returns to Lecce from Rome where he has been living and working for years, that Raffaele got to see a reproduction or print of the painting, and it is rather likely, therefore, to believe that this was the conduit that allowed Raffaele Maccagnani to come to know the work of Jules Breton. Comparing Jules Breton’s painting and Raffaele Maccagnani’s, we can see how the Lecce painter somehow tried to diversify and personalize the subject, choosing a different color palette and representing the young peasant girl in a landscape context that could be that of the Salento countryside. Moreover, the depiction is set in broad daylight and not in a twilight atmosphere as in Breton’s painting. The bright star Capella, the shepherds’ guide in the long nights across the fields, is replaced by a sheep hence the obvious and inevitable change in the title of the work: l’Étoile du Berger (the Shepherd’s Star) is transformed into La Pastorella (The Shepherdess).

In the course of my study I also found that at the Valerio Terragno Private Collection in Lecce there is a drawing by Raffaele Maccagnani entitled La contadina (The Peasant Girl). This is certainly the drawing executed by Maccagnani at the time when he decided to reinterpret Breton’s work: interestingly, the sheet in the Terragno Collection (33x23cm) is almost the same size as the print (32x24cm) reproducing theÉtoile du Berger preserved at the Musée Carnavalet in Paris. We can assume, therefore, that Maccagnani reproduced Breton’s subject from one of the many prints in circulation, almost certainly a color print, and did so through the use of squaring, dividing both the original and the white sheet into squares then helping himself with these guidelines to reproduce the drawing. Raffaele Maccagnani copies Breton’s work by adding the sheep to the composition, after which he paints the picture on canvas whose measurements are almost twice the size of the squared drawing.

La Pastorella was exhibited in August 1924 at the First Exhibition of Salento Art, a cultural event conceived and strongly supported by journalist and scholar of Salento culture Pietro Marti (Ruffano 1863 Lecce 1933), a review in which 57 Salento artists competed with 400 works of pure, applied and industrial art. The Salento artist died the following year, on August 9, 1925, at his home in Lecce’s historic center at 59 Via Idomeneo.

Raffaele Maccagnani devoted his entire existence to teaching and art without, however, managing to distinguish himself for originality much less inventive ability. In his artistic production he consciously - and not “probably unconsciously imitating,” as Vittorio Imbriani wrote in 1868 - traced the example of the most celebrated models and artists, revealing himself, nevertheless, to be a very skilled portraitist with great descriptive ability, as evidenced by the numerous paintings preserved in private and institutional collections in the Salento capital. On the one hand Jules Breton and Raffaele Maccagnani, two provincial painters with different human and artistic paths, and on the other hand Arthur J. Secor and Maurizio Aiuto, two collectors and art connoisseurs whose generosity made it possible to share and compare two pictorial works that otherwise would have remained locked in a private space and enjoyed only by a select few. This was intended to highlight the importance of donations from private collections to public institutions for a more complete knowledge of the history and events related to the area.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.