From eikon to crucifixion. The demonic in Medusa

There is a link between horror and beauty. The beauty of the human face is sometimes so intense that its magnificence cannot be sustained, and the eyes are forced to turn away. Moses himself cannot sustain God’s gaze, for his beauty turns out to be all too pure and dazzling. For his part, horror, on the other hand, is contained by beauty. For terror to be neutralized and made bearable by the human eye, it needs to beobjectified and entrusted to a body, a figure-symbol: theeikon. An effigy that has strong symbolic visual power, whose purpose is not to idolize a god, but which succeeds in averting the power of theéidolon, the spectral entity that returns to haunt the realm of the living. In the beginning it is the terror of death that stirs in man the need for protection toward the entities of the afterlife. And so it is that theeye, the most intelligent of the five senses, generates the object that can represent terror and consequently ward off the world of night. Medusa is the figure-symbol of this: theeikon that embodies terror. The effigy, the most ancestral depiction man has ever created. Its gaze is turned to the earthly underworld; it is not meant for the human eye since it is meant for the dead. Medusa has no need to cast out any living person, and for this reason no living person can bear to see it.

In the earliest artistic references dating from the early 8th and second half of the 8th century B.C. in ancient Greece, the Medusa is unwatchable, monstrous: such is the case with the scene depicted on the olpe with Perseus killing the Medusa in the British Museum (550-530 B.C.C) in which the Gorgon is presented with masculine features that trigger revulsion, and of the Archaic Medusa in the position of the “Knielauf” scheme (kneeling running scheme) from the 580 B.C. Temple of Artemis in Corfu. The eye is unable to support her gaze: the hair on her face is of all, the masculine element that makes her extremely disturbing. The protruding tongue, the eyes fixed and defiant against the viewer, the long fangs and serpentine hair give her charm and ambiguity in all depictions.

Medusa appears gigantic and deformed, a direct descendant of the titans and infernal creatures that ruled the earth in an indefinite time. As an ancestral figure, she summons to her the dark forces of earth and night. The origin of the figurative type of the Gorgon and its similar manifestations are also widely spread in the world of Asia Minor. In fact, the terrifying looks of other Mesopotamian demons, such as the face of Humbaba or Pazuzu were adopted long before Greece assumed the creature into its artistic repertoire.

And just as demonic faces are already present in African and Eastern cultures, the relationship between woman and snake, too, is already present in archaic and pre-Greek civilizations. The totemic figure of the Great Mother Goddess of Crete for example, represented with snakes coiled around her arms and pelvis, is already present in Minoan times (3000 - 1200 B.C.) and is alien to male domination and power.

Great goddesses and women represented the dual balance of everything: creators and destroyers, they were free and wild, mothers and virgins, they were the guardians of life and death. Since ancient times, a link has been attributed between the lunar landscape of chaos, darkness, and ambiguity, and woman. The moon has a 28-day cycle, exactly the same as that of the woman. The serpent itself is linked to the lunar landscape: terrifying, nocturnal, subterranean. It is not part of this world; it is part of the underworld. With its periodic skin change, it is a symbol of eternal becoming, of creative force, of ancient knowledge. With the advent of the archaic period in Greece, the serpent became associated with the darker sides of female power. It is no accident, therefore, that the term “Gorgon,” from the Greek Gorgón and derived from Gorgós is translated into our language as “terrible, fierce, grim.” The bond between woman and the serpent intensifies and acquires demonic character with the coming of Christianity. In Eden it is the demonic serpent that tempts Eve, and Lilith herself on earth surrounds herself with the same creature, as depicted by John Collier in 1892. The alliance between the feminine and the reptilian becomes even darker and the cause of men’s mortality.

Preceding the demonized Lilith, the Archaic-era Gorgon possesses a dual function: she is both the primitive representation of the afterlife and the symbol of protection itself against the realm of the dead. It protects the living in battles.

A theory against the beheading of Medusa also argues for an evolution whereby from the beheaded head of the Gorgon came the creation of both the total figure of Medusa and her inclusion in mythical traditions concerning Perseus, in order to give credibility to the Gorgoneion, the protective shield on which her image is reflected. Medusa is the guardian who stands between the two worlds: that of the living and that of the dead. She is the personification of primal instincts, she is the horrid versus the beautiful, the world of reason and order, of logos, and at the same time that of chaos and irrationality.

Dante himself includes the creature in his Inferno, guarding the walls of the City of Dis. Only from the mid-fifth century in Greece, from the Classical and form-balancing period, continuing into the Renaissance and modern eras, does Medusa change: the masculine features transform and become more human. The forms soften, she becomes feminized and more lovable. The eyes begin to bear the sight of her. The head of Medusa, decapitated by Perseus, fascinates, attracts and kills through its murderous gaze, but it is no longer terrifying. The horror of the hissing face and the terror of the geometrizing frontality of the Archaic Medusa is replaced by the hedonistic contemplation of the work of art. Chaos is dominated by reason.

The Medusa, fearsome and at the same time harmonious, succeeds at this stage in embodying the two faces of the human psyche: the face that cages man and urges him to contemplate the beautiful and makes him a social animal, and that of man with primal, animalistic instincts. Such is the case of the Medusa Rondanini, a marble face depicting the head of Medusa, but a copy probably of a piece dating back to the Hellenic age. The first case of a “beautiful Gorgoneion” as it has been renamed, it opens the door to a different, often mournful effigy. From protector, the Gorgon becomes a martyr. Her face no longer represents terror, but becomes human. Comparable to the suffering Christ on the cross, Medusa retains her demonic and seductive nature. Indeed, the modern creature carries the weight of the tragedy of the act to which she is mythologically connected: her beheading. Despite the negative interpretation, in modern times the character of Medusa enjoys no small importance, especially in the field of art. If the ancient Gorgon represents a monster and a guardian, the new Medusa symbolizes grief and tragedy and loses her protective power. She cannot be called theeikon of the past. Her beheading represents the loss of values, the loss of power, a crucifixion. In 1545 Benvenuto Cellini dramatically depicted the instant following her death, sculpting a triumphant Perseus holding her head in one hand and her sword in the other. The decapitated young woman’s body remains at her feet. In 1598, in the Baroque period, Caravaggio painted his newly decapitated head whose open eyes and gaping mouth convey the atrocity of the scene, creating the most famous and important shield in all of art history. Not far behind him, in 1640, master Bernini would produce a sculpted head in marble whose features show the suffering head at the exact moment of its change from woman to serpentine monster, as Ovid recounts in his poem The Metamorphoses.

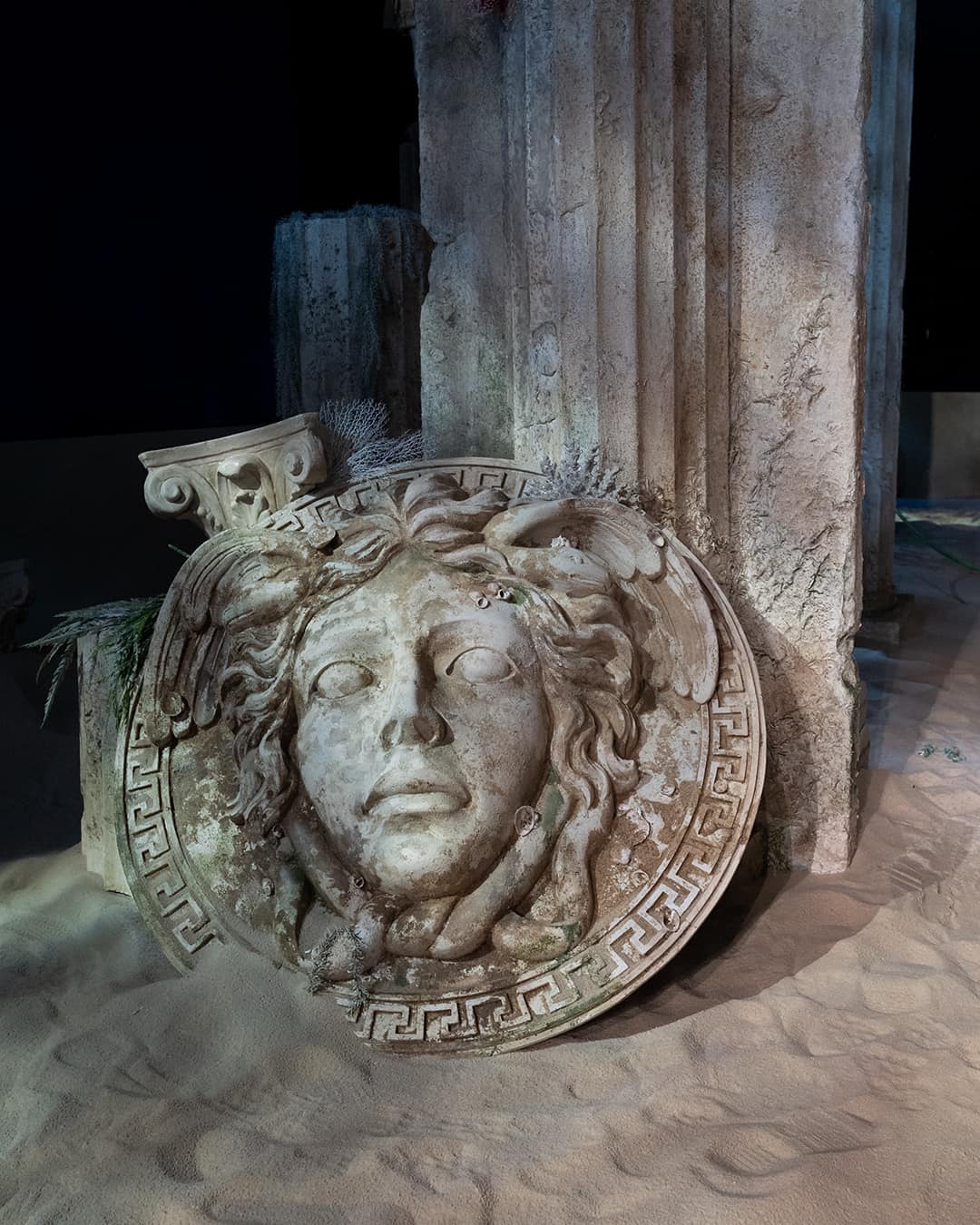

During Neoclassicism and during theArt Nouveau period her figure was revived and placed in medallions richly decorated in gold, such as Vincenzo Gemito’s 1911 medallion. In this context, the link between Medusa and the horrid is completely overcome, leaving room for a new bond that unites the Gorgon with the beauty that makes her acquire a glorious and impassive aura. In 1992 the great photographer Mimmo Jodice immortalized her face Gorgoneion Puteoli carved in stone among the ruins of ancient Pozzuoli in a silver salt photographic print and included her in his photographic book Mediterraneo.

Damien Hirst, on the other hand, sculpted the work The Severed Head of Medusa (2008) adding it to his collection Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable. It is a sculpture whose pained face holds its mouth wide open in an agonizing mute cry. In fact, what makes Hirst’s Medusa so interesting is not the facial expression, but the material with which the artist created the work. There is a stone, the dust of which produced in the process is highly toxic: it is malachite. Hirst decides to use it to carve the head, and its toxicity succeeds in giving expression to both the sculpture and rendering the myth at its best. In the following years he makes several heads, with different precious materials: gold, rock crystal and bronze. Fascinating and different from each other, they echo Caravaggio’s head in form, and among all of them, just the bronze one is studied by the artist as a piece of art found on the ocean floor. The snakes are cut into pieces and put on display alongside the face covered by corals and the false corrosion of the metal that occurred in the water.

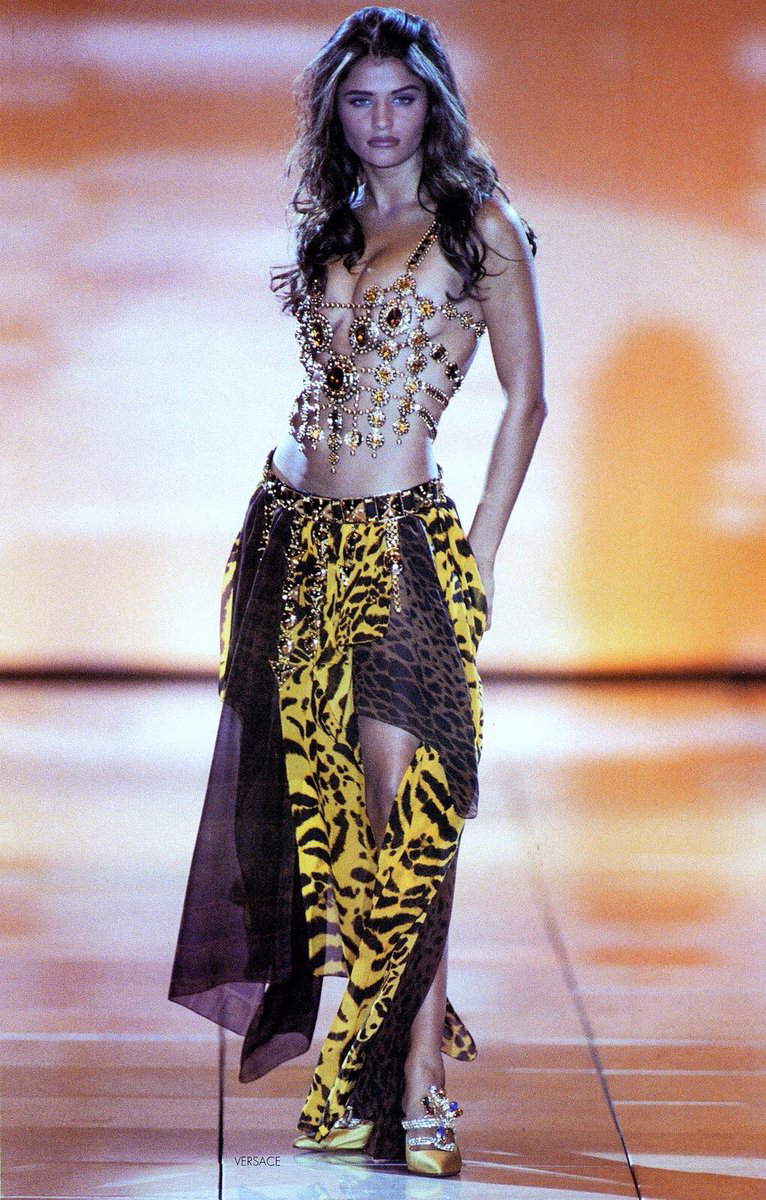

In the 1990s, Gianni Versace, fashion designer and founder of the Maison Versace, finely analyzed the different aesthetic aspects as well as the symbolic ones, totally reevaluating the character of Medusa. He managed to turn its stereotype upside down by mutating the hideous figure into an immortal and seductive woman, capable of bewitching men and petrifying them with the beauty of her gaze and her clothes. Born around the 1950s, Versace was born into a Calabrian family. The same land, formerly Magna Graecia, became fundamental to the creative development of his work. His mother Franca Versace has the most important tailoring shop in all of Reggio Calabria, while his father is fascinated by the world of ancient art and opera. From the combination of these three components Versace manages to build his own empire from the neoclassical style and taking classical mythology as an example to follow in the creation of his clothes. The memory of the remains of an ancient Roman mosaic depicting the Gorgon led Gianni Versace to choose Medusa as the logo and symbol for his Maison. “When I had to choose a symbol, I thought of the ancient myth: he who falls in love with Medusa has no chance. So why not think that those who are conquered by Versace cannot go back?”

So why is the Medusa so represented and loved by artists? Because it is a creature that does not belong on this earth. It is mystery, fascination, venom, power. It is terrifying and at the same time becomes suffering. Of all female creatures, the Medusa is the one who comes closest to the Divine and the Demonic. The artist seeks to decipher her riddles, to capture her torn and destructive soul and to imprison the toxicity of her gaze in matter. And it is she herself, through her magnetism that bewitches the artist, bringing him to a higher state of consciousness.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.