The story of the Japanese marathon runner Kōkichi Tsuburaya could be taken as an example to explain how the ancient Greeks, the inventors of the Olympic Games of Antiquity, viewed what we would today call sports competitions, even though a Greek of, say, twenty-five centuries ago would have a hard time understanding our concept of “sport.” Tsuburaya participated in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, and finished third in the marathon won by Ethiopian Abebe Bikila (best known for his marathon triumph at the 1960 Rome Games). The Japanese athlete won the bronze but was overtaken in the final moments by Britain’s Basil Heatley: he was deeply ashamed that he had lost the silver just in the home stretch. “I made an unforgivable mistake in front of the Japanese people,” he said shortly afterward. “I must make amends by running and hoisting the Hinomaru at the next Olympics in Mexico.” Tsuburaya was suffering before the idea that he could not win the next Olympics, so he underwent grueling training ahead of the 1968 Mexico City Games. His body, however, was unable to sustain the effort, and the Japanese marathon runner collected a series of injuries: a herniated disc, low back pain, and an Achilles tendon injury. In pursuit of his dream, he had also lost his fiancée: one of his superiors (Tsuburaya was in fact a lieutenant in the Japanese army) told him that he could not marry before the Olympics, and her parents, in the harsh Japan of the 1960s, were unwilling to keep her waiting, so they forced her to leave her beloved. It was the straw that broke the camel’s back: on January 8, 1968, a few months before the Olympics, Tsuburaya took his own life by cutting his carotid artery. Legend has it that he was found dead holding his bronze medal.

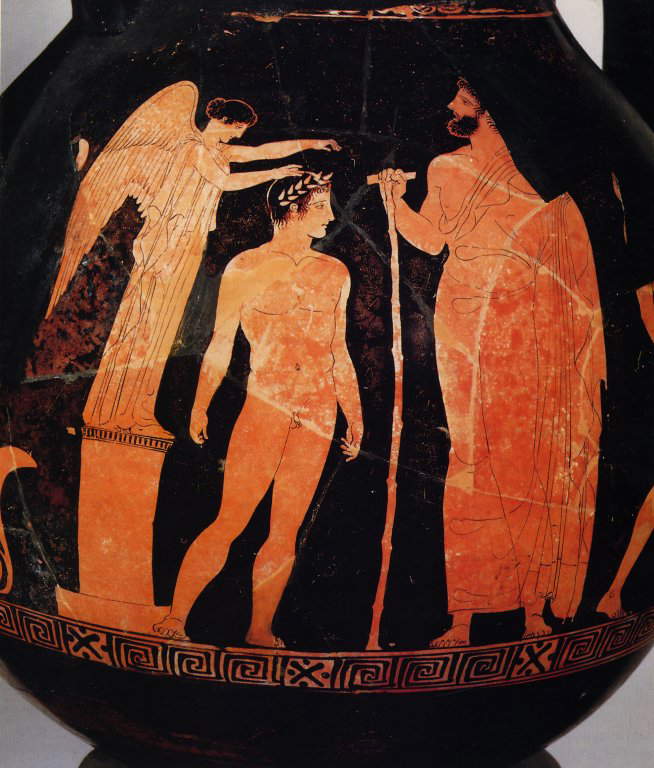

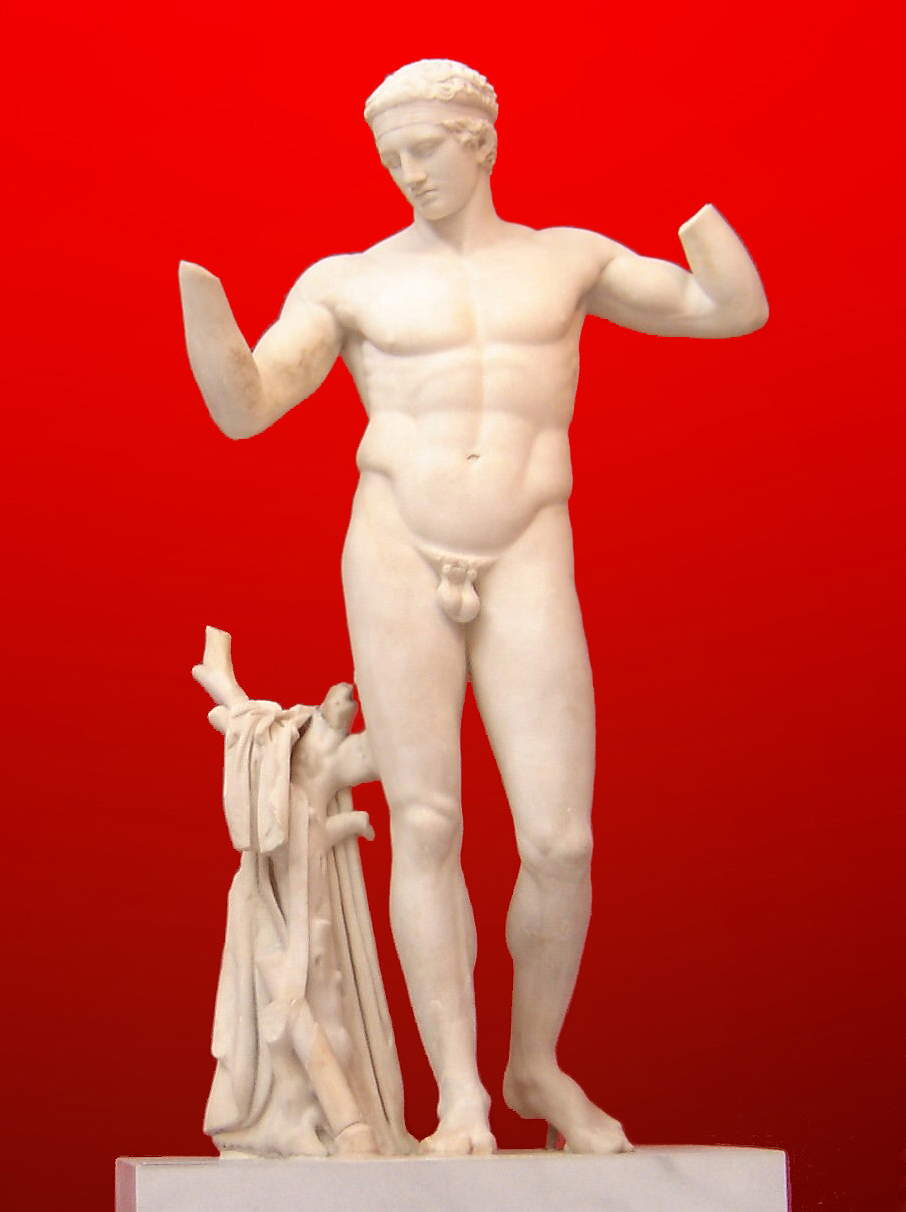

Tsuburaya is considered a victim of the Olympics-his suicide has often been read in relation to the life of hardship he had accepted to live in the hope of winning the Games. The mentality of victory at all costs, of the deep shame felt in the face of failure, was characteristic of the athletes of ancient Greece, where no credit was given to second to third: there was only victory, it was only first place that mattered. We find a clear echo of this mentality in Pindar’s eighth Pythian Ode , dedicated to an athlete, Aristomene of Aegina, winner of the wrestling competition at the Pythian Games, which we quote in Ettore Romagnoli’s 1927 translation: “Three prizes, Aristomene, with opra vincesti. / And over four you plummeted / bodies, and loomed fierce. / Nor, as to you, granted / Pythus playful return / to them, nor come to their mothers, / a laugh of gentle joy encircled them: / by oblique trammels they trembled, / dodging the hostile, / wounded by enemy fate.” The awarding of the winners, during the editions of the Olympic Games, did not always take place in the same way (it should be remembered that the Olympics of antiquity lasted from 776 B.C. until 393 A.D.). According to an early tradition, the winners of all competitions in the ancient Olympic Games were awarded only at the end, when all the competitions had taken place: in the time between the competition and the award ceremony, however, the winner could walk around with ribbons and bows tied to his head, arms and legs, signaling his status. The formal award ceremony took place at the temple of Zeus in Olympia: the winner received as an athlon, that is, as a prize (an “athlete” in Greek is literally “one who competes for a prize”), an olive wreath (it was not everywhere like this: at the Pythian Games, the crown was laurel, at the Isthmian Games it was pine, while at the Nemean Games it was wild celery) and a sash to be tied around the hair (we see a typical example of this in Polyclitus’ Diadumenus ).

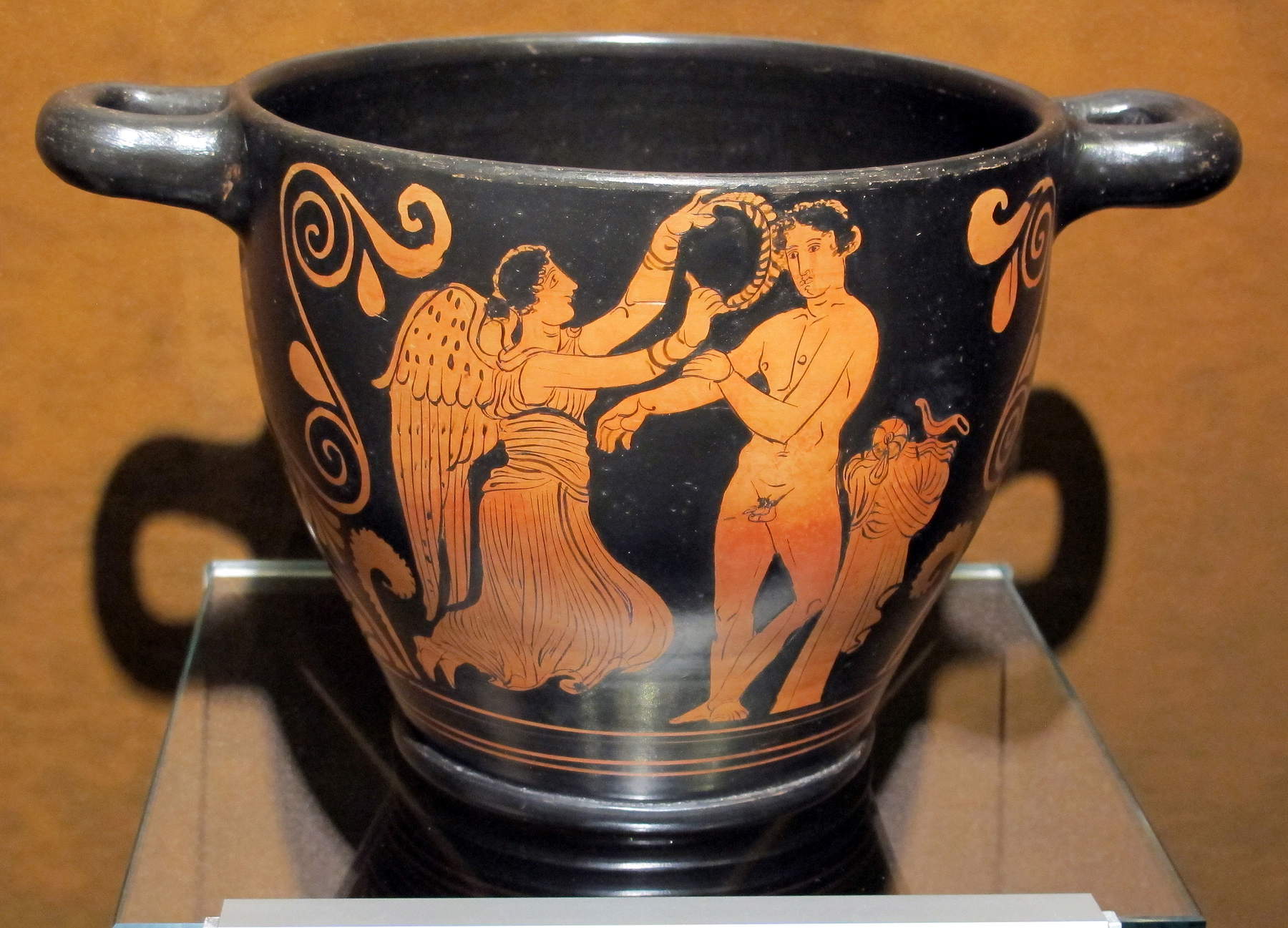

The sash was given before the award ceremony, while the coronation took place during the official award ceremony: the winner was proclaimed “the best of the Greeks” and could attend a special banquet to which all the winners were invited. Scholar Judith Swaddling summarizes the tenor of the festivities as follows, “In addition to the public banquet for the winners, various private celebrations were held in the evening. Wine flowed freely and there was singing and revelry. Winners and friends adorned themselves with garlands and paraded around the Altis singing victory hymns, which were either traditional songs or odes composed especially for the occasion by prominent poets such as Pindar or Bacchilides. The richer the victor, the grander and more luxurious the celebration. Both Alcibiades of Athens and Anaxilaus of Reggio organized magnificent feasts to celebrate their victories. Empedocles of Agrigento was a disciple of Pythagoras and consequently a vegetarian. He prepared an ox of dough garnished with expensive herbs and spices and distributed it among the spectators. Often the feast continued all night, and the next morning the winners (who hopefully did not compete again that day) made solemn vows and sacrifices to the gods.” The symbolic moment of the winner’s coronation is also found on many Greek ceramics: usually, placing the crown on the athlete’s head, as seen in an Attic pelike (a wide-mouthed liquid vessel) preserved in the National Archaeological Museum in Tarentum, or again in a skyphos (drinking cup) from the Musée Olympique in Lausanne and several other examples, is the goddess Nike, the deity of victory. If the victorious athlete could afford it (since the burden was on him), he could also boast of a statue dedicated to him that was erected in the Altis, the valley where the temple of Zeus stood (the statue could, however, also be financed by the winner’s friends, or by the state). There were, however, competitions that also guaranteed athletes prizes in kind: this is the case of the Panathenaic Games, which took place every four years in Athens, and which guaranteed the winners, as a reward, olive oil contained in amphorae, the Panathenaic amphorae, many specimens of which can also be seen in Italian museums, since several have been preserved. These amphorae all followed the same decorative scheme: on one side, a depiction of the sport in which the athlete had reported victory, and on the other side, the figure of the goddess Athena in profile accompanied by the inscription “Ton Atenethen Athlon,” or “The Prize of the Athens Games.”

Then, once back home, the winners were often further celebrated. It must be said that in the context of the most important games of antiquity, including those of Olympia, the prizes up for grabs were only symbolic: the athletes therefore did not receive awards in money or in kind. However, the situation was different when the winners returned home. Often, in fact, the home states of the athletes who had triumphed at the Games awarded their champions decidedly substantial prizes: large sums of money, or foodstuffs, free housing, and so on. In Athens, for example, the legislator Solon had determined that the winners of the Isthmian Games would be rewarded with 100 drachmas, while 500 drachmas was the sum provided for the Olympians, the winners of the Olympic Games: a considerable sum, since 500 drachmas corresponded to what a wealthy Athenian earned in a year.

However, the only glorious return allowed in ancient Greece was indeed that of the victor: for the defeated there was no glory. Today, it is we who, in turn, struggle to understand this idea (there are, of course, no shortage of exceptions: there are athletes for whom the only permissible outcome to a competition is victory, although they are now increasingly the exceptions): for us, sport is first and foremost about commitment, hard work, the pursuit of a goal that presupposes the beginning of an arduous journey aimed not so much at winning as at giving one’s best. Of course, even today winning is extremely important, but the modern concept of sport also has to do with enjoyment, personal growth, respect for the opponent, and according to Pierre de Coubertin’s well-known principle, it is more important to participate than to win, and this is often true for many athletes who participate in the modern Olympics, especially when they know they are dealing with technically and physically better prepared opponents: for many, the dream is above all to take part in the world’s most important sporting event, rather than to win it. It was different for the ancient Greeks: only winning mattered. This is because in ancient Greece, the games had originated as competitions in preparation for military activities: in the vision of the ancient Greeks, sports competitions were a kind of simulacrum of war, and war, it is known, sees only one winner; there are no prizes for the second or third place finisher. As a result, finishing second or third was of no significance to the Greeks, so much so that the names of what we now consider silver or bronze medals are not even recorded in reports on the Games of antiquity. Ties were not allowed either: in case of a tie, the winner’s crown was dedicated to the presiding deity of the Games. And sporting competition as a preparatory activity for war was also the rationale with which politicians used to justify the heavy expenses that the various cities of Greece or Magna Graecia or Asia Minor incurred to enable their athletes to train, as well as to maintain the facilities. Indeed, much of the sporting competitions have military origins: think of javelin throwing, boxing, wrestling, discus throwing, or even just running and long jumping, skills useful for pursuing enemies or for crossing ditches.

The equivalence, however, is not full. “It is true that it can easily be argued that some of the events have a military origin,” wrote scholar Robin Waterfield, “but in reality the skill in the Olympic events would rarely translate into the kind of skills needed by a typical Greek soldier. [...] The seventh-century Spartan poet Tyrtheus even doubted that athletic prowess necessarily developed the kind of courage needed in war. And in one of his plays, Euripides, a fifth-century Athenian playwright, had a character (we don’t know who) say, ’Will they fight the enemy with discs in their hands? Will they drive the enemy out of the homeland by piercing their shields?’ Euripides’ sarcasm is justified. For fourteen successive Olympic festivals in the fifth century, beginning with the 70th Olympiad in 500 B.C., there was a mule-drawn chariot race. This was clearly not intended to simulate anything that might have happened in war. Also, there were no team sports competitions, which presumably would have been useful in a military context.” Although they had a war origin, the Games still remained an end in themselves, and in this they closely resembled modern sports. “The link between war and sport,” according to Waterfield, “worked only in the sense that both activities developed strength, endurance, discipline, and courage, and because the ethos (and thus the vocabulary) of athletic competition mirrored that of war, and both required violence restrained by adherence to rules.”

The idea of rewarding the top three finishers at sporting events is all modern , and the now-classic gold, silver and bronze succession made its first appearance at the 1904 St. Louis Olympic Games, the third edition of the modern era. In the previous two, the winner received a silver medal and the runner-up a bronze. However, the runner-up, in the official reports of the first Olympic Games, was never a “runner-up.” He was, if anything, a “second-place winner.” The idea of victory, compared to ancient times, had already changed considerably.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.