Throughout the twentieth century, one of the great merits of fashion (and fashion photography) has been that it has played a key role in popularizing art, helping to disseminate artistic motifs to social groups that were more unlikely to be in contact with various artistic experiences.

Many haute couture fashion houses, such as Dior, Chanel, Jean Paul Gaultier, and Louis Vuitton, today collaborate with artists not only in the making of their garments, but also in the execution of photographic campaigns, fashion show fittings, and collection promotion. The case of Dior is perhaps the most emblematic. Christian Dior, founder of the fashion house that bears his name, was an admirer of art, a friend of many important names of the early 20th century avant-garde: Salvador Dalí, Pablo Picasso, Juan Miró, Max Ernst, Giorgio De Chirico. The art-fashion union has always been present in the history of the fashion house, from Marc Bohan, who in 1984 had created a collection based on the works of Jackson Pollock, to Gianfranco Ferré, Dior’s creative director in the early 1990s, whose collections were openly inspired by Titian, Rembrandt, Céfangs, to John Galliano who had reinterpreted Gustav Klimt in 2008, to creative directors in the last decade, Raf Simons and Maria Grazia Chiuri, who have forged collaborations with artists such as Sterling Ruby, Pietro Ruffo, Marinella Senatore, Sharon Eyal, Paola Mattioli, and Matteo Garrone.

|

| Marc Bohan’s dresses inspired by Jackson Pollock (1984). |

|

| John Galliano’s dresses inspired by Gustav Klimt (2008) |

While it is true that fashion has almost always sought to build channels of confrontation with art, for the latter, fashion has been a ground for critical debate that has many times led to remarking on its role other, especially in terms of commercialization.

The debate between art and fashion, fundamental to the artistic movements of the twentieth century, had its first expression in 1863, when Charles Baudelaire, in his essay Le peintre de la vie moderne, in which he first conceives theidea of the flâneur, refers to “gravity in the frivolous” (“gravité dans le frivole”) and suggests a new awareness of fashion as an artificial paradise with which to dress in modernity. Fashion as a modern attitude: as a way of thinking, feeling, and acting in modernity, with obvious allusion to the work of Charles Frederick Worth, the first to establish a maison couture in Paris in 1858. With an anticipatory look at the times, Baudelaire well understood that shortly thereafter the phenomenon of fashion would in a sense make the work of artists more popular and commercial.

The historical avant-gardes and cultural movements of the early twentieth century have often and willingly dialogued with haute couture, although this dialogue has always remained marginal within art history and criticism. We do not always remember, in fact, that the Futurists had written two manifestos on the subject: The Antineutral Dress (1914) and The Futurist Women’s Fashion Manifesto (1920), to which Giacomo Balla himself had made an important contribution.

Another experiment in combining art and fashion was undertaken by painter Sonia Delaunay, whose Boutique Simultané (organized in collaboration with couturier Jacques Heim) was presented in the fashion section of the 1925 International Exhibition in Paris. The painter’s ’intent was to translate her paintings into fabrics and garments intended to encapsulate the frenzy of modernity. No less important on Delaunay’s part was her contribution to the costumes for Tristan Tzara’s first Dada show, Le Coeur à gaz, in 1923, which just over fifty years later would inspire clothes worn by David Bowie and Klaus Nomi.

Salvador Dalí, an exponent of Surrealism, had also collaborated in the 1930s with Elsa Schiaparelli, for whom he designed the “hat-shoe” (1937), the “organza dress with lobster” (1937) and the “tear-dress” (1938).

Sociologists and cultural critics such as Georg Simmel and Walter Benjamin wrote about fashion, stating how it was one of the main means by which modernity manifests itself, as well as contributes to the construction of one’s identity and the “spirit of the age.”

|

| Sonia Delaunay’s costumes for Tristan Tzara’s Le coeur à gaz (1923) |

|

| Elsa Schiaparelli and Salvador Dalí, Lobster Dress (1937) |

|

| Elsa Schiaparelli and Salvador Dalí, Tear Dress (1938) |

There are two points of no return in the relationship between art and fashion, and both are linked to two magazines: in the first case it is the work of art that is represented in a fashion magazine; in the second, it is a haute couture garment that appears for the first time on a cover of one of the most important contemporary art magazines of the last fifty years.

1951 was the year that photographer Cecil Beaton did a photo shoot for Vogue magazine, at the Betty Parsons gallery in New York, in front of two poured paintings by Jackson Pollock, which in this case serve as a backdrop for the presentation of the latest women’s clothing. Art historian T.J. Clark was very critical of this attempt to relate art to the cultural industry that Vogue and the fashion world represented. In the early 1960s, the reflection on commercial art and fashion becoming art was deepened thanks to “pop” culture and its artists who tried to reset the distinction between high and low culture, deliberately refusing to distinguish between a design for a fashion garment and the work of art itself, as happened in the case of Andy Warhol and his The Souper Dress (1961). The debate centered on something from which the fashion industry could benefit and with which art would eventually have to compete.

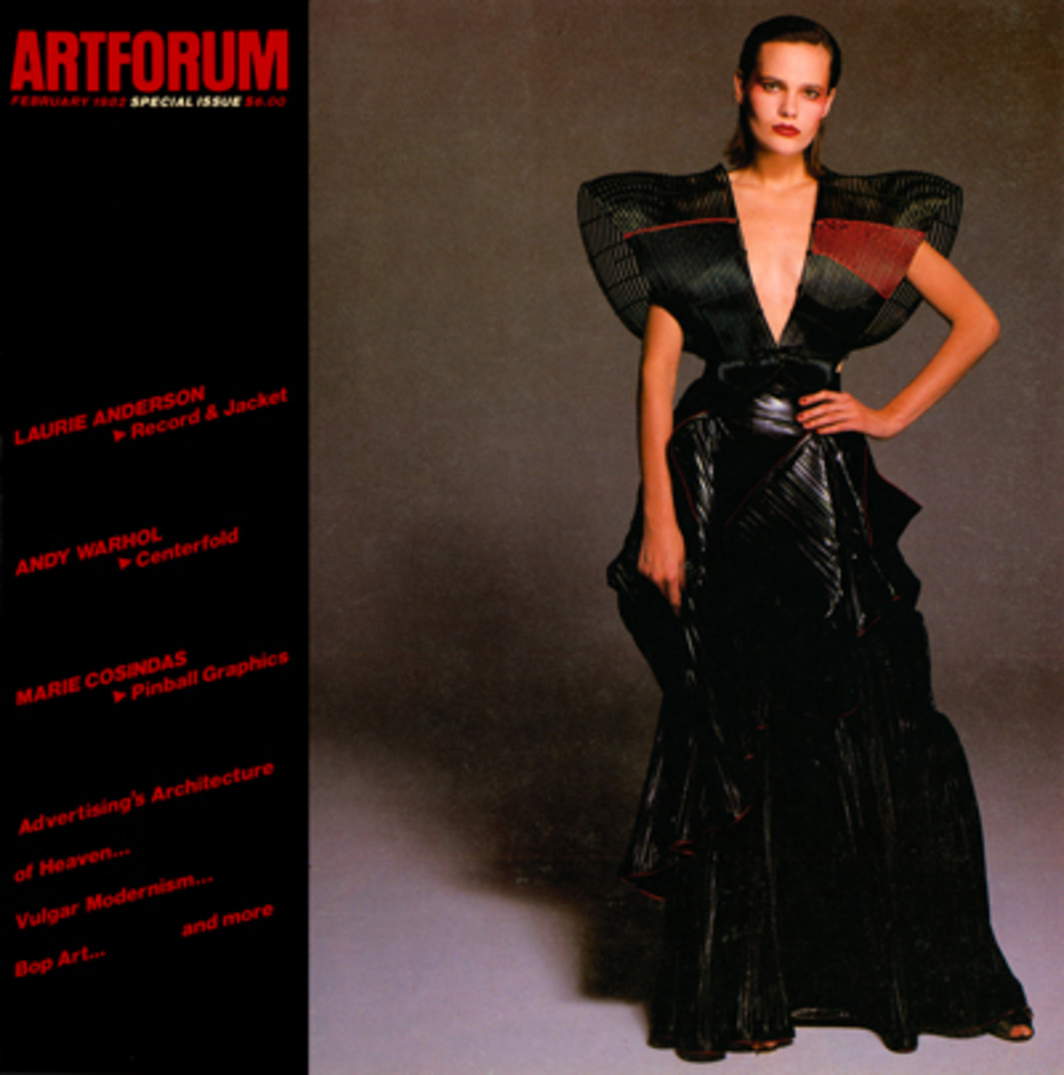

1982 was the year that a dress by Japanese designer Issey Miyake appeared on the cover of Artforum International. The editorial in that issue had the signatures of American writer Ingrid Sischy and Italian art critic Germano Celant, who argued that fashion could be considered a new kind of “artistic production that maintains its autonomy as it enters mass culture at the indistinct border of art and commerce” (Artforum International, Editorial, February 1982). Both understood that it was pop art that had first broken down the hierarchies between “high and low, pure and impure,” and “the useless and the useful.”

Beginning with this official recognition in the pages of the contemporary art magazine, some haute couture garments that by then had become historic, such as those by Yves Saint Laurent made in 1965 and based on the works of Piet Mondrian, began to be exhibited and acuired by contemporary art museums as was the case with the Met and the Yves Saint Laurent retrospective in 1983.

|

| One of Cecil Beaton’s photographs for Vogue (1951) |

|

| Andy Warhol, The Souper Dress (1966-1967; New York, The Metropolitan Museum) |

|

| The February 1982 cover of Artforum International. |

|

| Yves Saint Laurent’s Mondrian-inspired dress. Photo by François Larry |

|

| Melissa Marcello, The Warrior, self-portrait (2021) |

|

| Melissa Marcello, Nature (2020) |

|

| Melissa Marcello, Red (2020) |

In parallel, fashion photography has also received increasing attention, with several major exhibitions, such as the one at MoMA in 2004. This delay in exposure compared to “art photography” shows how it took a long time for fashion photography to be considered an art form. Very often it was excluded from major photographic exhibitions because it was considered too commercial. Today it is important to consider how, to the extent that fashion photography is increasingly accepted as art, fashion itself seems to be gradually moving in the same direction.

In recent years, there is an increasing interest by fashion photographers in the world of art photography with the intention of breaking down the differences between “high photography” and “low photography.” The medium is being used by professional artist photographers for fashion campaigns (such as the aforementioned case of Paola Mattioli for Dior), but also by emerging photographers for projects that combine pictorial art, haute couture and photography such as that of UTPICTURA by Milan-based fashion photographer Melissa Marcello. UTPICTURA combines art and haute couture, reinterpreting the past in a contemporary way with the intent of deconstructing the photographic portrait to achieve a new, textured image that holds only a memory of the past world without being a faithful copy of it. Among the aims of Melissa Marcello ’s project is precisely to make portraiture, which from an artistic point of view has always been an elitist genre, accessible to the masses, giving everyone a chance to be a part of it.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.