Collection [col-le-zió-ne] s. f. [from Latin collectio -onis, der. of colligÄ•re “to collect”]. - An orderly collection of objects of the same kind having value either for their intrinsic value or for their historical or artistic or scientific interest or simply for personal curiosity or pleasure: make c. of stamps, of coins, of medals; a c. of paintings, of statues, of cameos.

The first of the six meanings by which this noun is defined in the Treccani dictionary well specifies the fine art of collecting, which, contrary to what one might think, is a practice very well “rooted” in the cotidie vivimus of humankind. Without delving into anthropological reasoning that, although necessary, is beyond the centrality of this contribution, it is worth noting how “collecting” can be considered an attitude inherent inhomo sapiens who, eager to understand nature and its many manifestations, has always sought in every way to possess it and eternalize it in time. Place where this attempt to fix in an imperishable way the various nuances of creation - natural and man-made - is put into practice, becomes, without any doubt, the home: “treasure chest” in which a domestic microcosm is recreated.

Valuable evidence concerning the art of constructing spaces for the display of riches comes to us directly from the Naturalis Historia of Pliny the Elder, who, in his encyclopedic treatise describing the natural sciences, dwells on the scientific knowledge preserved in dwellings, for which he adopts terms such as cubiculum and pinacotheca(Naturalis Historia, XXXV, V, vv, 296-297). The presence of such spaces, moreover, had already been mentioned by Vitruvius in his De Architectura (35-25 B.C.E.) where, sketching the dwellings of wealthy citizens, in addition to vestibula, regalia and perystilia amplissima, he reports bibliothecas and pinacothecas (De Architectura, 6, 5, 2).

Such aspects, then, well highlight how already in antiquity this inherent human desire to collect was a common practice even if, in reference to those years, it seems decidedly more appropriate to use the term “collection”: the conscious activity of collecting, in fact, will appear with due meaning from the 15th century onward. Regardless of lexical nuances, the common thread linking the centuries-old custom of collecting can be found in the materiality of the hoarded objects, which, due to their variety, were divided into the two macrocategories answering to the name of artificialia and naturalia.

Natural “things,” in particular, from the Middle Ages onward found space inside churches where, parallel to relics, votive offerings and spolia, they came to constitute true “zoomorphic” collections, useful, through their symbolic value, to support the Christian word. As evidence of this, the Mantuan case of the Abbey of Santa Maria delle Grazie is particularly illustrative, in which the famous crocodilus niloticus, hanging from the nave and a true naturalia, symbolizes the victory of good over evil: the triumph of the Catholic faith. Other objects pertaining to the natural world that, fortified precisely by their symbolic aura, began to be collected inside churches also include the ostrich egg whose value, connected to the Immaculate Conception, is well recalled by the iconic Brera Alt arpiece or the Mantegna altarpiece of San Zeno.

It is certainly no coincidence that one of the first ante litteram collectors capable of setting up a striking and marvelous environment was the Benedictine Sugerius of Saint-Denis (Chennevières-lès-Louvres, c. 1080 - Saint-Denis, 1151). The abbot of the church of the same name, in fact, in open contrast to the pauperism professed by St. Bernard of Clairvaux, following what Pseudo-Dionysius described in his Mystical Theology, according to which God manifests himself to man through a golden cascade of light, endowed the abbey of Saint Denis with rich artifacts - sculptures, stained glass, pottery, precious stones, gems and enamels. Many of these objects from the Treasury of Saint Denis, collected to further the various pilgrimages, were also “updated” by Sugerius in a Christian key, as is well evidenced by the Eagle of Sugerius, a porphyry vase that the cleric himself enriched by endowing it with a gilded silver mount, decidedly more in keeping with the abbey environment.

Also in France, during the second half of the fourteenth century, another illustrious figure, Jean de Valois (Vincennes, 1340 - Paris, 1406), duke of Berry, constituted what, without a shadow of a doubt, can be considered in its own right one of the earliest collections of the time. In fact, the inventory of the collection of the third-born son of John II the Good, King of France, drawn up in 1416, gives an account of no less than 1317 objects-divided among tapestries, paintings, and goldsmithing-among which it is clear that the preponderant part of the collection turned out to be the manuscripts, which, given the refined culture of the duke, were illuminated by the leading artists of the time.

It is perhaps no coincidence that the distinguished French bibliophile was responsible for the creation of the Très Riches Heures, the famous prayer book illuminated by the Limbourg brothers between 1411 and 1412 that - completed, due to the sovereign’s death, only during the 1440s by Barthélemy d’Eyck - was to represent a valuable piece in Jean’s already rich collecting chessboard. The duke’s collection in addition to numerous other curios-among them no less than four narwhal teeth-was even more enriched by one of the most famous cameos of antiquity such as the Gemma Augusti.

At the dawn of the fifteenth century, therefore, the practice of collecting and the consequent setting up of ad hoc created environments began to gain considerable ground, supported also by the emerging antiquarian culture-Humanism. In Italy such a “display” conception began to develop with the establishment of the so-called Renaissance Studioli, of which the first and most striking example is to be found in the studiolo of Piero il Gottoso de’ Medici, maintained and later enriched by his son Lorenzo the Magnificent. Although today that room, built on the second floor of the Medici Palace located on Via Larga, is no longer visible, since it was destroyed by the modernizations carried out in the palace in the mid-seventeenth century, it is once again the inventories (1456, 1492) that inform us about the richness of the small room. The studiolo, in fact, a veritable treasure chest in which to store, study and, above all, display the preciousness collected, housed collections of coins, gems, semi-precious stones, and vases, all surrounded by floor and wall decoration enlivened by Luca della Robbia’s glazed terracottas, of which the twelve roundels of the Cycle of the Months represented a true unicum.

Another great protagonist of this bewitching artistic practice was Federico da Montefeltro, who, between 1476 and 1482, produced two studioli worthy of his cultural caliber. On the piano nobile of the Ducal Palace in Urbino, Federico created a veritable locus amoenus that, surrounded by a fine lacunar ceiling, was adorned in the upper register of the wall by twenty-eight Portraits of Illustrious Men while in the lower one refined wooden inlays, works by the Da Maiano, punctuated the space. These very ones, animated by illusionistic representations of half-open cupboards containing the most varied objects, represent perhaps better than anything else the intimate rarity of the room. The same dynamics can also be found in the Studiolo di Gubbio, which - alas, now housed in its entirety at the Metropolitan in New York - testifies to how such places where one can reflect on the arts and sciences, collected in themselves, were aspects particularly prized by the great humanists of the time.

Equally fascinating appears to be what was created by Isabella d’Este (Ferrara, 1474 - Mantua, 1539) who, upon the death of her husband Francesco II Gonzaga in 1519, decided to move her widowhood apartment to the ground floor of the Corte Vecchia in Mantua. Here she devised two more intimate and private rooms, the Studiolo and the Grotta, suitable for storing and displaying her own collection of works, which, consisting of natural curiosities and archaeological finds, boasted rare pieces such as the Ptolemaic Cameo and, above all, famous canvases commissioned from the best-known painters of the time, such as Andrea Mantegna’s Parnassus and Minerva drives away vice.

During the 16th century, numerous became the personalities of the great Italian courts who decided to create and allocate individual rooms for the display of their treasures(naturalia, artificialia, curiosa, exotica... ), so much so that the writing published in 1554 by Sabba da Castiglione is of extreme importance. In his Ricordi ovvero ammaestramenti, the Italian clergyman and humanist gives an account of the furnishing of private homes of the time, pointing out how many adorned their dwellings “with antiquities, as of heads, of trunks, of busts, of ancient statues, of marble, of bronze [...] of papers embossed in copper [...] of ray cloth and celons that came from Flanders [...] of fantastic et bizarre things [...] of many beautiful et artificial things.” The writing instructs on the precious treasure chests that the illustrious (and cultured) personalities of the time constituted, proving also a useful key to understanding all those spaces still in the making. Friar Sabba’s descriptions, in fact, appear fully useful for reading the Tribuna built by Bernardo Buontalenti between 1581 and 1583 on commission of Francesco I de’ Medici (Florence, 1541 - Poggio a Caiano, 1587). The room, designed to “hold the most precious jewels and other honorable and beautiful delights that the Grand Duke has,” represents at best a summa of all the aspects described so far and, more importantly, can consistently be defined as the first true Italian Wunderkammer. An absolute Chamber of Wonders made all the more sumptuous through the rich exaltation of the four natural elements distributed as follows: the Earth, imprinted on the floor through the reproduction of a flower-like sunburst inlaid in refined polychrome marble; Water, manifested through the use of 5.780 mother-of-pearl shells for the gilded ceiling decoration; Fire, enhanced by the fine red velvet walls; and Air, “personified” by the lantern which, placed at the apex of the octagonal room, provided almost divine illumination thanks to its eight stained glass windows.

Beginning in the mid-16th century, Wunderkammer began to spread at major European courts, especially in the transalpine territories, where the more “rigid” Renaissance artistic culture gave way to a decidedly more “Gothic” conception. This is the case with the famous Chamber of Wonders of the Duke of Tyrol and Archduke of Austria, Ferdinand II (Linz, 1529 - Innsbruck, 1595). Beginning in 1570 at the well-known Ambras Castle in Innsbruck, the ruler began work on the construction of the so-called Unterschloss, the “lower castle,” the purpose of which would be to house the duke’s riches. Indeed, the latter’s collection was one of the most articulate and varied of the period, so much so that it included more than 120 suits of armor, disparate rarities, and a large picture gallery. The Royal Armory, the Wunderkammer and the Hall of the Spaniards, not surprisingly, still form the central framework of the museum itinerary. Although the rare 15th-16th-century armor and the illustrious picture gallery-which consists of valuable pictorial testimonies such as Titian, Van Dyck, and Velazquez-witness the cultural importance of the collection and its creator, what is most striking are the “extraordinarily” objects collected by Ferdinand. Crystals, bronze sculptures, goldsmithing, weapons, naturalia-all these rarities formed an unprecedented Wunderkammer whose exquisiteness can be well explicated by the Korallenkabinett, a wooden cabinet lined internally with black velvet, punctuated by refined mirrors with gilded borders and adorned with mythological figures made of one of the rarest, most expensive and unique materials on the entire globe: coral (pink, red and leap).

Remaining still in northern Europe, remarkable similarities can be found with the equally famous collection of Rudolf II of Habsburg (Vienna 1552 - Prague, 1612), a controversial character who was extremely fascinated by the natural, alchemical, and scientific ways, and who constituted in the 1680s one of the richest collections of the time. He gave rise to one of the most famous Wunderkammer, which, later dismembered in the direction of Vienna because of the Thirty Years’ War, in addition to the well-known portrait Vertumno (by Arcimboldo), consisted of absolute rarities well exemplified in the narwhal horn now preserved at the Kunsthistorisches in Vienna.

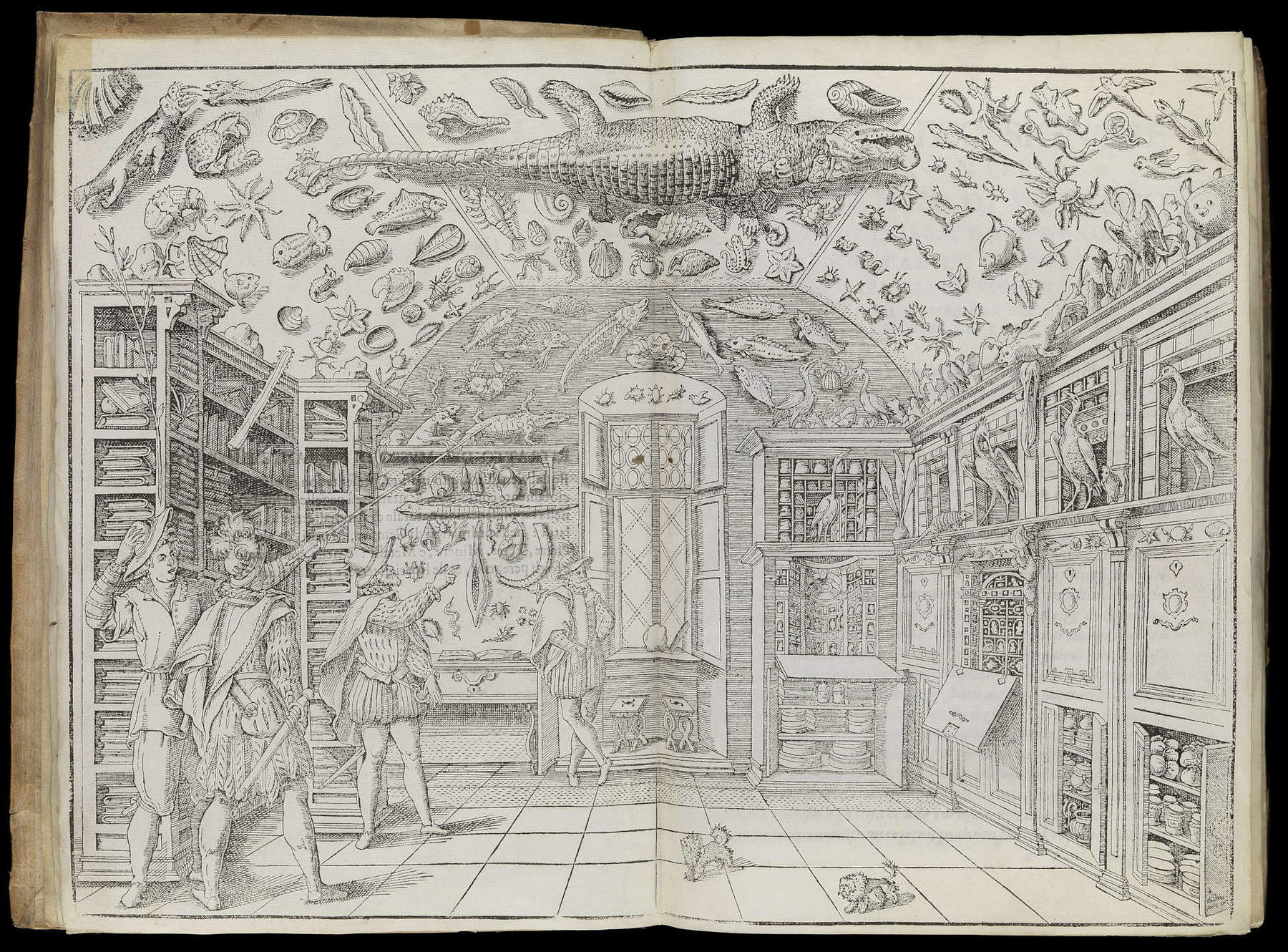

Scavalizing into the 17th century and crossing the Alps back to Italy, of considerable interest appears to be what was set up in Rome, and more specifically in the Collegio Romano, by Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680). An outstanding scholar of mathematics, physics, alchemy, astrology, and Egyptology, it was precisely at the Roman seat that the Jesuit began a collection of the most disparate objects that led him to create a Wunderkammer centered, primarily, on the display of scientific objects that would help in the understanding of the cosmos.

Beginning in 1727, thanks to Caspar Friedrich Neickel’s seminal paper, Museographia, the Wunderkammer found its own definition and its own accomplished exhibition “regulations,” laying the foundation for the formation of the “Temple of the Muses” that today, again with the same and unchanged fascination, we call a “Museum.”

This contribution was originally published in No. 17 of our print magazine Finestre Sull’Arte on paper. Click here to subscribe.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.