Blue BlueBlue. This is the title of Dino Buzzati’s review of the exhibition Monochrome Proposals: Blue Era, a solo show held by Yves Klein in 1957 at the Apollinaire Gallery in Milan. A title that immediately draws attention to one of the traits that made Klein famous: the insistent use, often in monochrome canvases, of the blue tone that would take the artist’s very name. Lent for the occasion to art criticism, Buzzati sharply frames Klein’s eclectic personality: “born in Nice twenty-eight years ago; nautical and oriental language studies; racehorse trainer; judo champion in Japan itself.”

The French artist, situable in the bed of Nouveau Réalisme, had then arrived in Italy with eleven blue and one red monochrome painting. He had struggled to convince the customs officers of the artistic nature of those objects. But it was in Milan that he inaugurated the blue era that would consecrate him. Klein’s relationship with that color and with color in general had a relatively long history (however long one might precisely consider the artist’s career, condensed into less than an astonishing decade, from 1955, the year of his first public exhibition at the Club des solitaires in Paris, to 1962, the date of his untimely death).

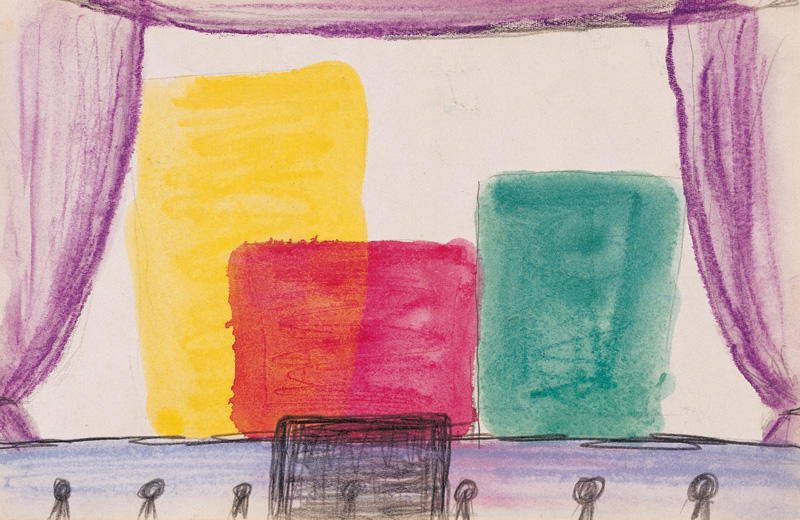

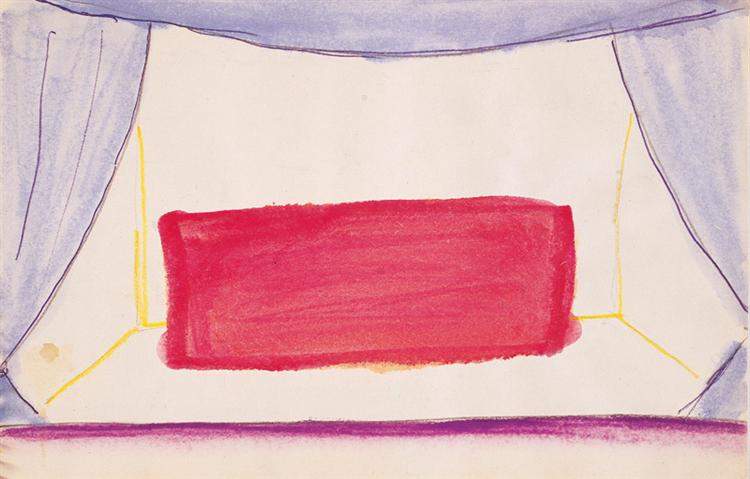

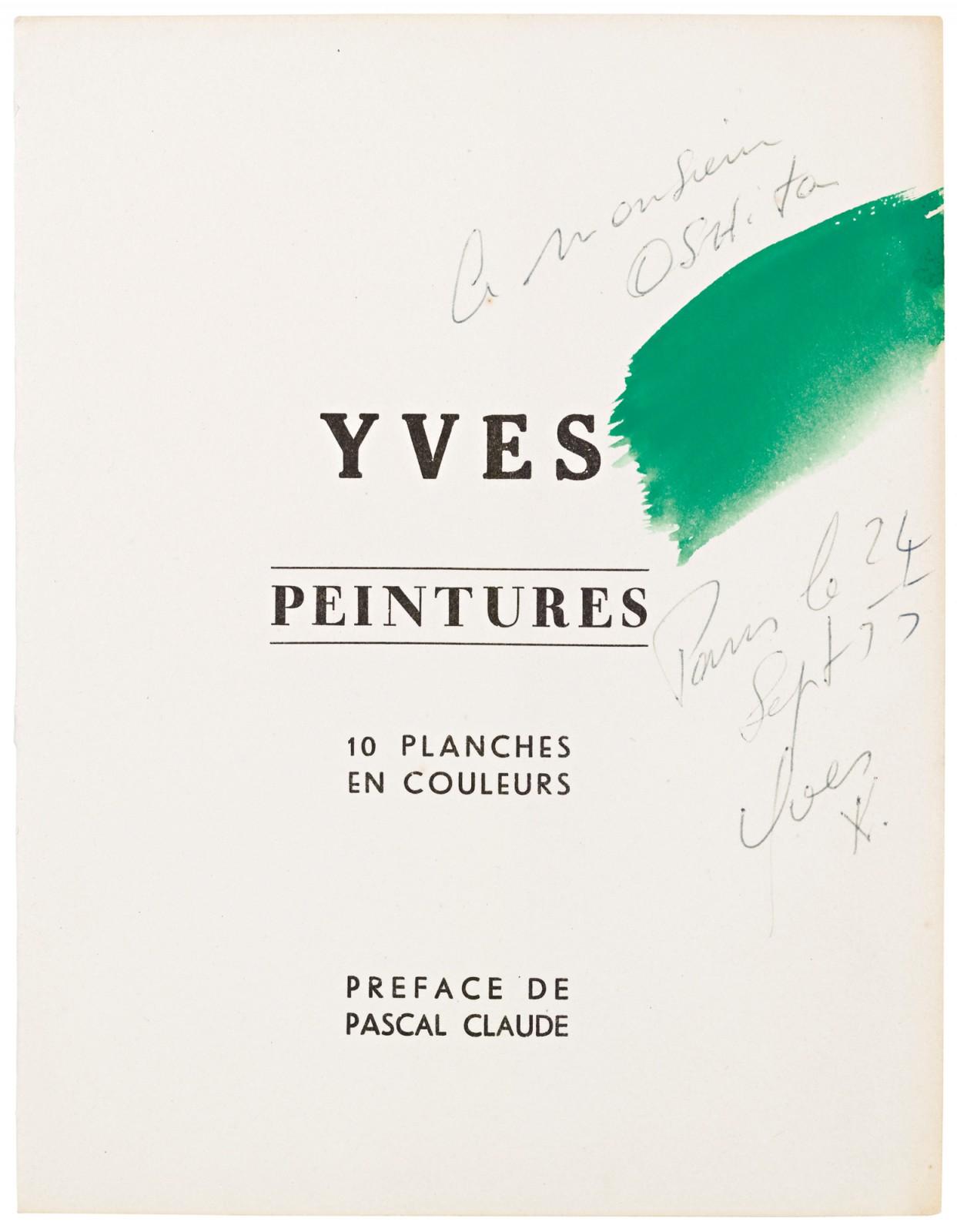

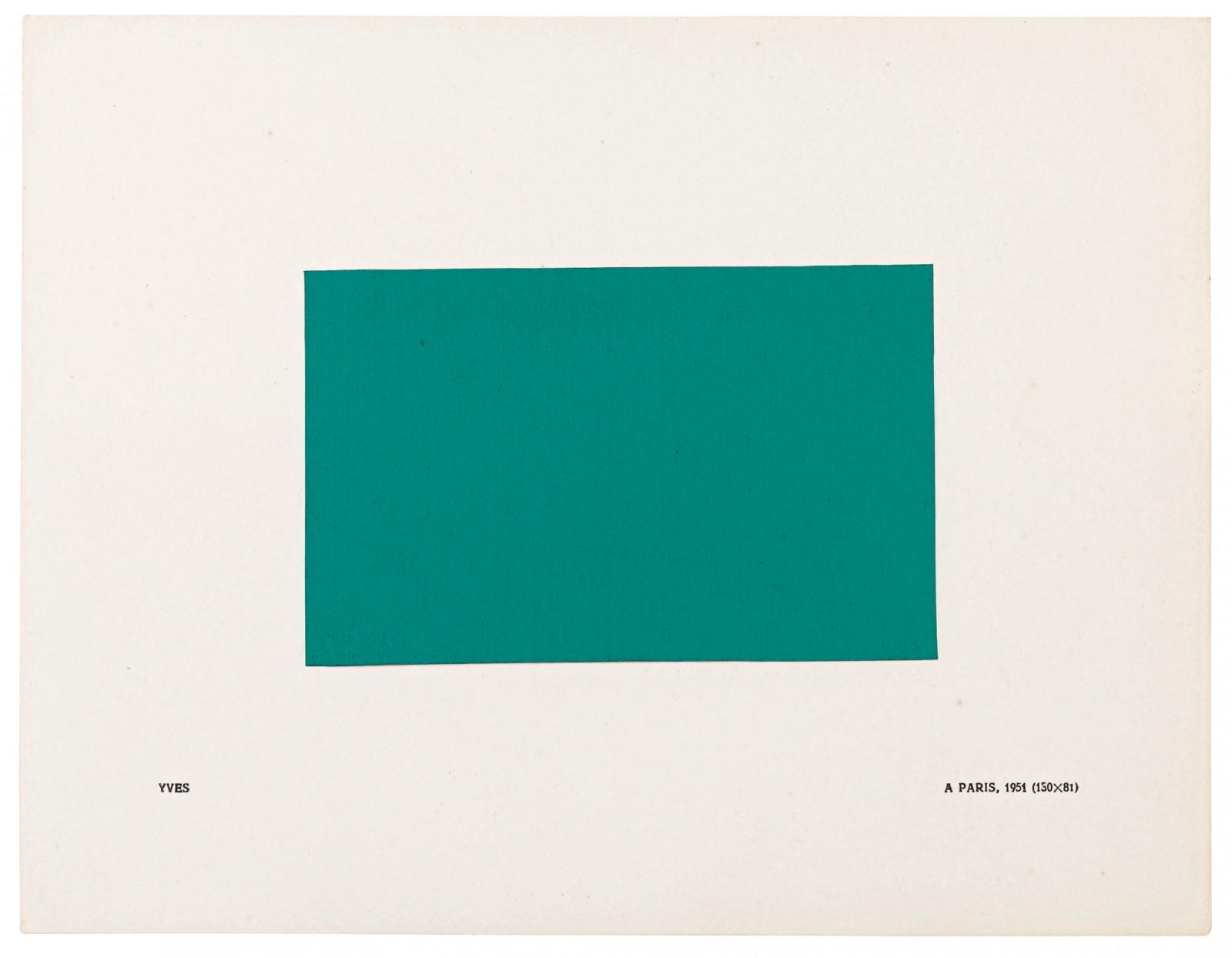

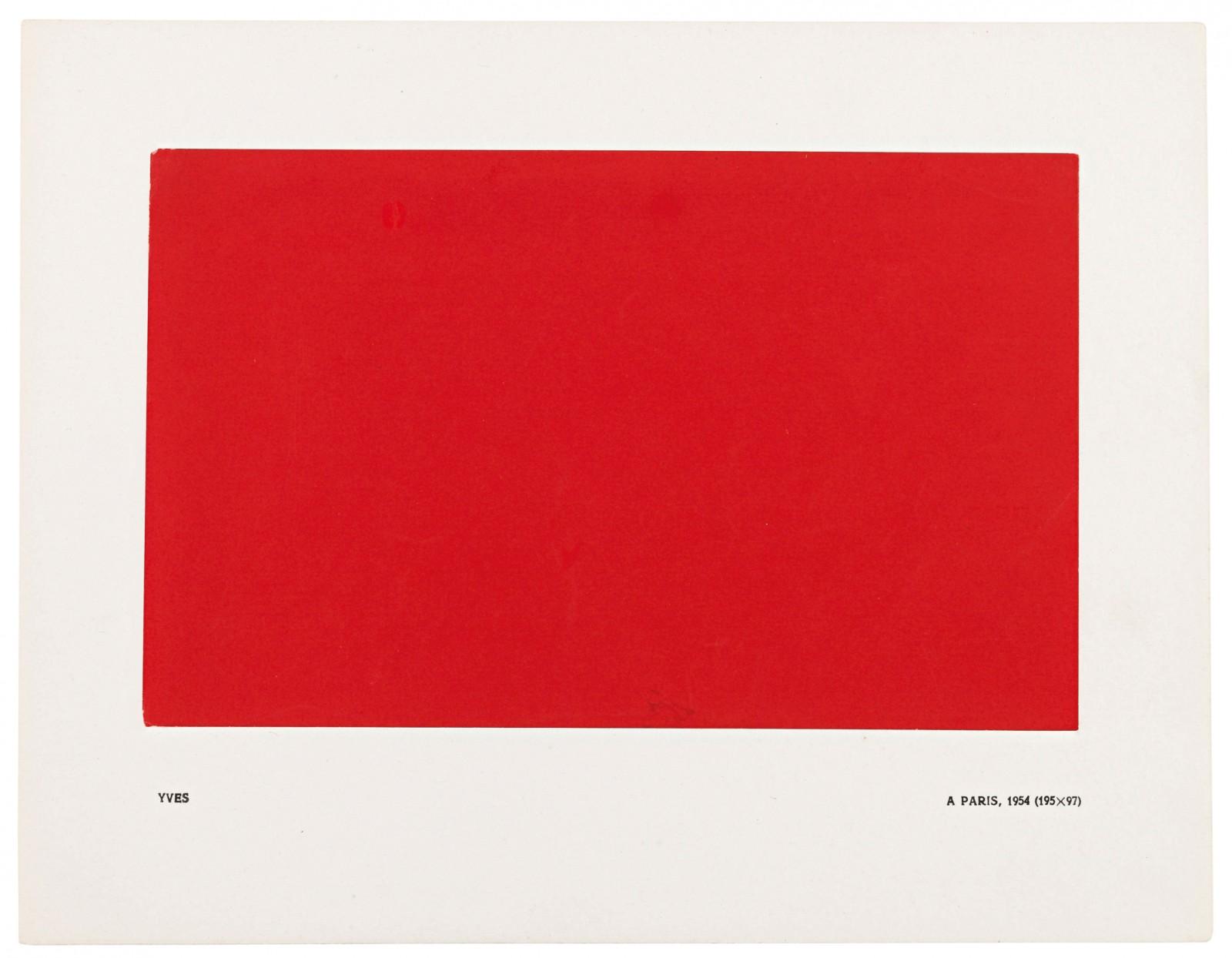

Klein’s first monochrome steps can be traced in some watercolor sketches made in 1954 and titled Monochrome jaune, rouge et vert (scéne de théâtre) and Monochrome rouge (scéne de théâtre). Contained in a spiral-bound notebook, the sketches present monochrome rectangles in the center of a stage framed by classic red curtains. From the same year is the catalog Yves Peintures, a controversial work with which Klein, in his early days, attempted to introduce himself and legitimize his proposal in the art world. In fact, the works reproduced here, ten monochrome plates, varying in color and size, preceded by a singular introduction by his friend Claude Pascal, consisting only of horizontal black lines, seem never to have been created.

|

| Portrait of Yves Klein made on the occasion of Peter Morley’s film The Heartbeat of France in 1961, studio of Charles Wilp, Düsseldorf |

|

| Yves Klein, Monochrome jaune, rouge et vert (scéne de théâtre) (1954; watercolor and pencil on paper in spiral notebook, 133 x 210 mm; Private collection) |

|

| Yves Klein, Monochrome rouge (scéne de théâtre) (1954; watercolor and pencil on paper in spiral notebook, 133 x 210 mm; Private Collection) |

|

| Yves Klein, Yves Peintures, catalog of plates on paper, copy dedicated to Monsieur Oshita (Paris, September 24, 1955; paper, 245 x 190 mm; © Succession Yves Klein c/o ADAGP, Paris) |

|

| A panel from Yves Peintures |

|

| A panel from Yves Peintures |

Klein’s actual career began the following year, in 1955, with the two Paris exhibitions that preceded the Milan show. In Yves: peintures and in Yves: propositions monochromes the paintings, strictly monochromatic, free of lines and figuration, which in Klein’s poetics represent an unnecessary constraint, are still of various colors and reflect the artist’s conviction that to every color corresponds an entire world.

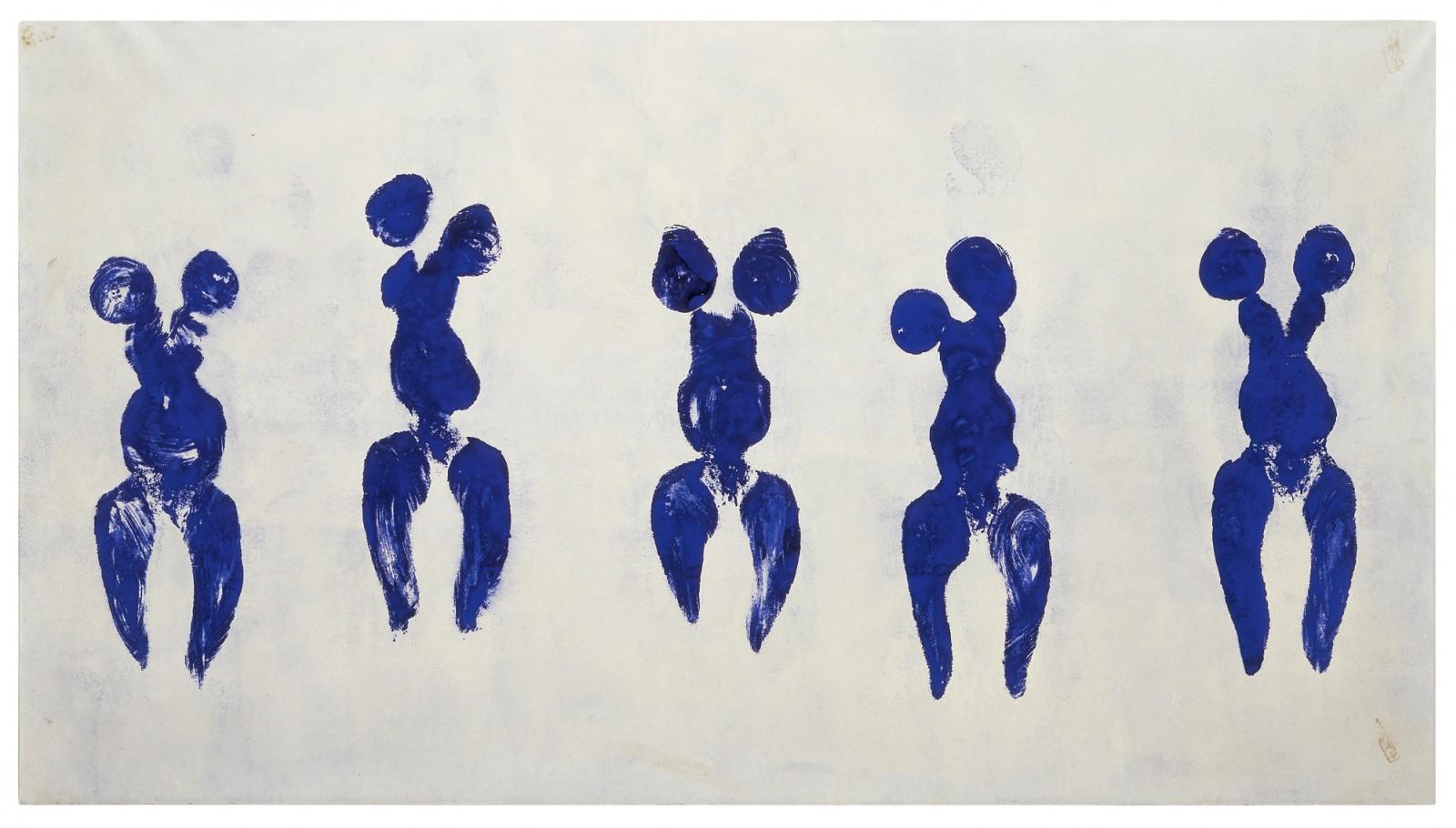

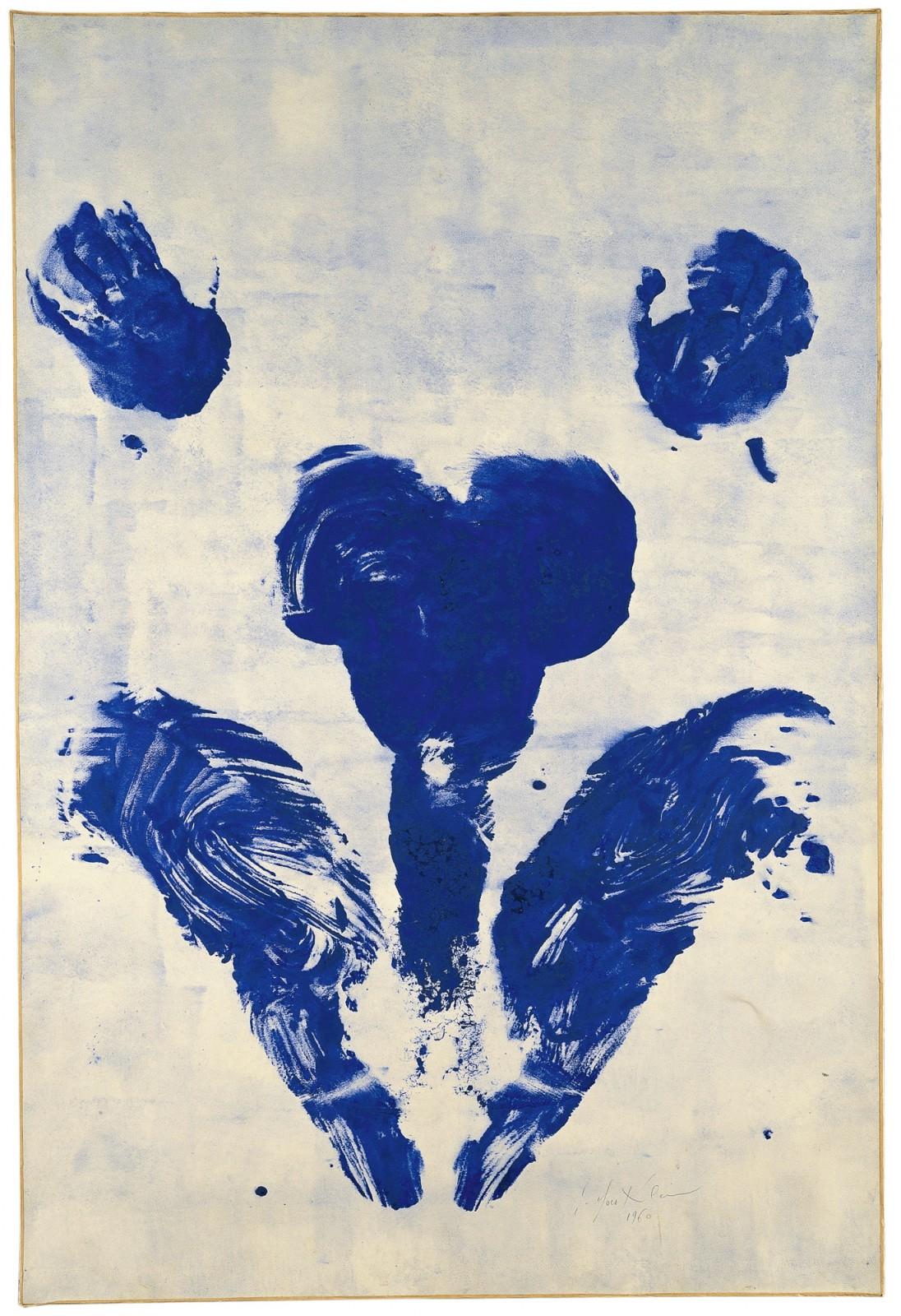

The path that would later lead Klein to focus exclusively on blue is explained by the artist himself in a lecture given at the Sorbonne on June 3, 1959, and later taken up in several publications. At the second Paris exhibition, the artist had noticed that visitors, instead of sinking into the “abstract idea represented in an abstract way” that he intended to communicate (as per the author’s text introducing the exhibition), were dwelling on the decorative beauty given by the juxtaposition of the various colors. They thus misunderstood the artist’s true intention. In order to avoid viewers’ lingering on the color combinations and to draw attention to his abstract art, Klein therefore resolved to reduce his palette and vote his artistic life (almost) to a single color: blue. The masterpieces of the period, exhibited between the Tate Gallery in London, Centre Pompidou in Paris, MOMA in New York and the Louvre Abu Dhabi, are the Anthropométries, Sculptures Éponges, Portraits Reliefs and some blue reinterpretations of famous works such as Michelangelo’s Dying Slave or Nike of Samothrace.

But why precisely blue? It is again the talk at the Sorbonne that provides an answer. The artist (also revealing some of the philosophical suggestions underlying his work: the studies of Gaston Bachelard, above all), states that blue, unlike all other colors, would have no dimensions. It would stand outside of space and time. And for that very reason it would lend itself to his purely abstract vision. Of this solution Klein also finds an illustrious artistic precedent, even discerning it in Giotto: “I was shocked in Assisi, in the basilica of St. Francis, by the scrupulously monochrome, uniform, blue frescoes that I think I can attribute to Giotto [...]. The blue of which I speak is precisely of the same nature and quality as the blue of Giotto’s skies that can be admired in the same basilica on the upper floor. Even admitting that Giotto had only the figurative intention of showing a pure and cloudless sky, this intention, however, is really monochrome.”

|

| Yves Klein, Anthropométrie de l’�?poque Bleue (1980; pigment and synthetic resin on paper mounted on canvas, 156.8 x 282.5 cm; Paris, Centre Pompidou). © The Estate of Yves Klein c/o ADAGP, Paris |

|

| Yves Klein, Anthropométrie sans titre “Héléna” (January 1960; pure pigment and synthetic resin on paper mounted on canvas; 109 x 74 cm). Ph. David Bordes. © Succession Yves Klein c/o ADAGP, Paris |

|

| Yves Klein, Sculpture �?ponge bleue sans titre (1959; pure pigment and synthetic resin on natural sponge mounted on stone; 114 x 56 x 30 cm). © Succession Yves Klein c/o ADAGP, Paris |

|

| Yves Klein, L’Esclave de Michel-Ange (1962; pure pigment and synthetic resin on plaster, 46.5 x 12 x 11 cm). © Succession Yves Klein c/o ADAGP, Paris |

|

| Yves Klein, Victoire de Samothrace (1962; pure pigment and resin on plaster mounted on stone; 49.5 x 25.5 x 36 cm). © Succession Yves Klein c/o ADAGP, Paris |

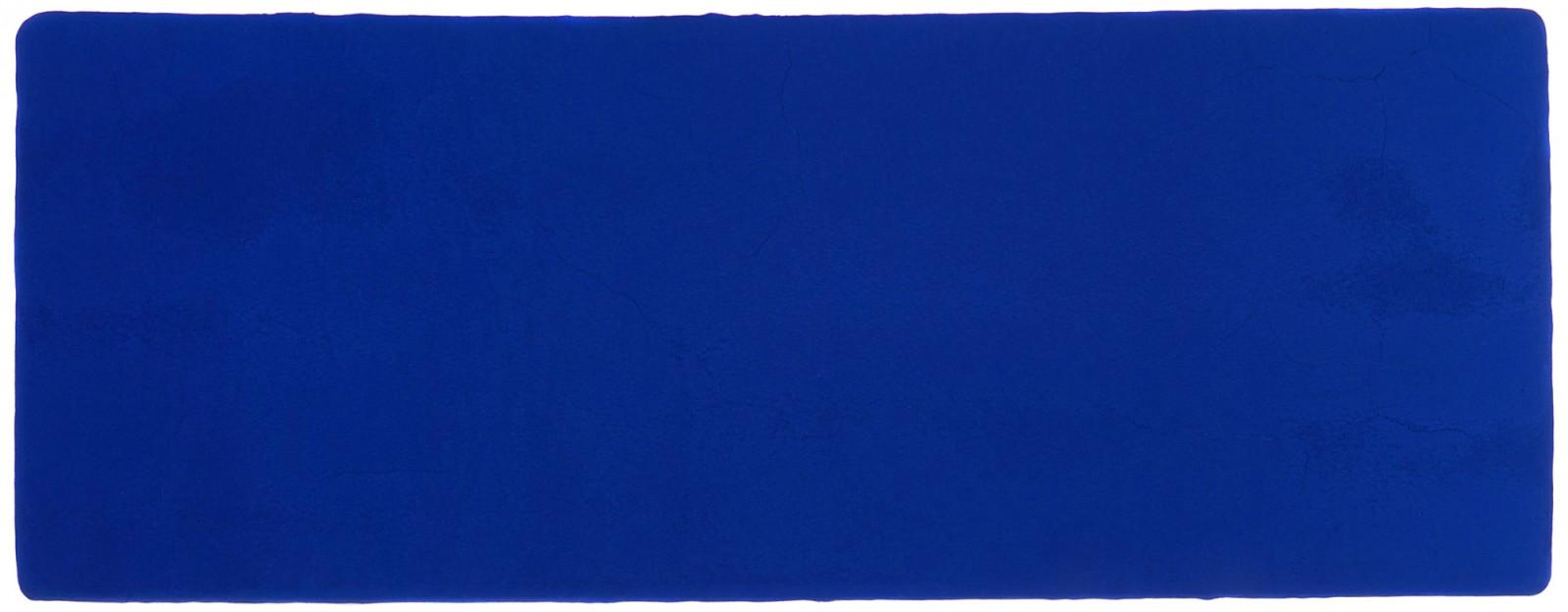

In 1956 Klein devised a formula to achieve “the most perfect expression of blue”-a blue that is brilliant , pure, luminous, and unalterable over time. Assisting him in the endeavor were Edouard Adam, owner of a dye works in Montparnasse, and an engineer friend of his, an employee of a chemical and pharmaceutical company. Mixing ultramarine 1311 powder, Rhodopas M60 A (a resin at the time newly commercialized), 95° alcohol and ethyl acetate, Klein obtained a color he christened International Klein Blue (I.K.B.), filing its patent with the Institut national de la propriété industrielle in 1960. At the same time, the artist assumed the pseudonym Yves Le Monochrome, initiating an increasingly driven process of identifying himself and his art with the blue of his own invention that would lead him to outcomes attributable to performance art.

In Milan, Klein achieves his goal in this way: the public (among whom are two exceptional visitors: Lucio Fontana and Piero Manzoni) is able to recognize different atmospheres and essences in his paintings, all ultramarine blue, all made with the same technique and all of the same size, but each with a different price tag. Buyers are willing to pay dissimilar amounts for essentially the same works because they distinguish in each work a singular pictorial quality, which evidently lies not in its material aspect but in what Klein calls “pictorial sensibility.”

Interesting in this sense is the period that succeeds the Blue Era and represents its consequent evolution. In fact, Klein’s research ends up flowing naturally into a reflection on the concept of the ’indefinable’ (a notion taken from the diaries of one of the great masters of modern French art, Eugène Delacroix, whose heir Klein felt himself to be in a certain sense). This aspect is explored in the 1958 Paris exhibition known as Le Vide (The Void). In a 1961 article Klein would write, “while I always continued to paint monochrome, I almost automatically reached the immaterial.” A statement that is well clarified in relation to the working title of Le Vide: Exaspérations monochromes.

|

| Yves Klein, Monochrome bleu sans titre (IKB 129) (1959; pure pigment and synthetic resin on gauze mounted on board, 15.5 x 40 cm; Ulm, Ulmer Museum). © Succession Yves Klein c/o ADAGP Paris |

|

| Yves Klein, Monochrome bleu sans titre (IKB 216) (1957; pure pigment and synthetic resin on gauze mounted on board, 60 x 40 cm; Münster, Westfälisches Landesmuseum Museum für Kunst und Kultur). © Succession Yves Klein c/o ADAGP Paris |

|

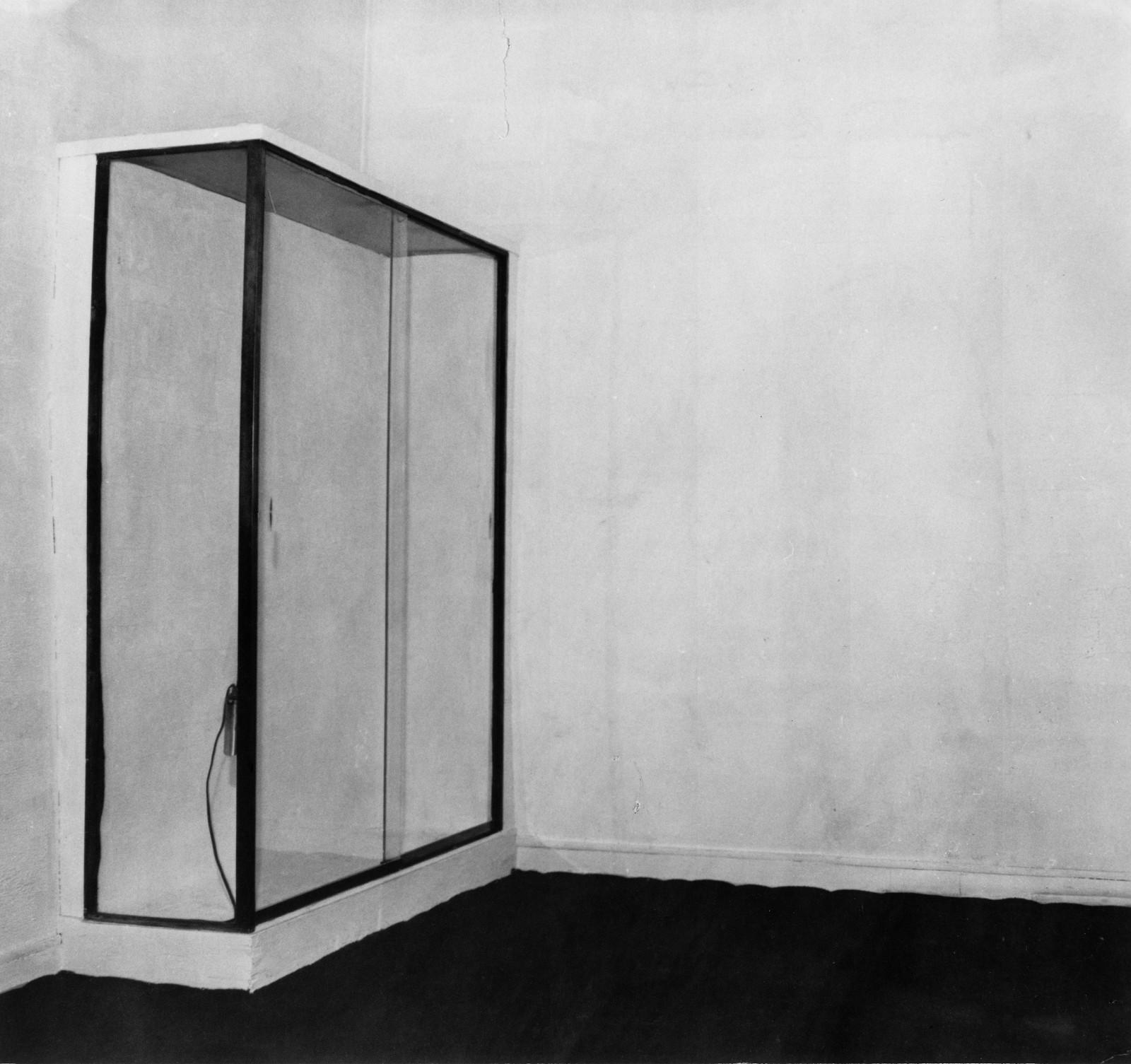

| Entrance to the exhibition Le Vide. La spécialisation de la sensibilité à létat matière première en sensibilité picturale stabilisée (Paris, Galerie Iris Clert, April 28 to May 12, 1958) |

|

| Hall of the exhibition Le Vide |

It is by taking his extremism in blue to extremes that Klein achieves an immaterial blue, a color of the void: in Le Vide the artist in fact presents a room painted entirely white and filled, as it were, exclusively with ’pictorial sensibility.’ Even on this occasion, however, blue remains the guiding thread of the exhibition, conceived as a great initiatory rite for the public into Klein’s artistic world. Blue welcomes visitors right from the outside of the gallery, where a canopy and blue balloons are set up. The exhibition is then entered in small groups, only after sipping, in a sort of ceremonial fashion, a blue cocktail made of gin, Cointreau and methylene blue (of which participants would be surprised to find traces in their urine the next day!).

Klein’s experimentation would continue around the idea of emptiness, arriving by this route at a progressive dematerialization of the work of art (the artist would even go so far as to sell pieces made up of only pictorial sensibility, that is, entirely immaterial), the paradoxical character of which would be excellently highlighted by Albert Camus, who upon the release of Le Vide would write: “Avec le vide, les pleins pouvoirs.” With the void, the full powers to abstractionism long pursued by Klein. Such a strand of research, very high in conceptual terms, represents a great, but now necessarily intangible, legacy of Yves Klein’s experience. Of that, however, we are left, preserved in the world’s most important museums, with the germinal phase, the generating cue: the most indelible of his colors. Klein blue.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.