We harbor, mostly unconsciously, the fierce belief that the works of art kept within the walls of museums will remain available to the world forever that they will somehow survive us by escaping old age and escaping the inexorable decline typical of human beings. How, then, to behave when one discovers a worn-out canvas that is beginning to sag, shrivel and slowly perish? This is the challenge faced by restorer Muriel Vervat after the discovery of a scruffy Nero con punti by Alberto Burri from 1958 using an approach quite different from the restoration techniques traditionally used in the West. In 2019, the work was sent to Florence to be investigated and treated by the restorer in collaboration with specialists from the CNR and the University of Pisa. It was decided, thus, with extreme calmness and apparent simplicity, to “cure” it by accompanying it in aging using a product of plant origin extracted from the Japanese Funori seaweed. An element, this one, already used for centuries in the East for the restoration of all those typically porous materials such as papers and fabrics, but almost unknown in the West. The lower half of the canvas had suffered substantial falls of the paint film and the breakage of a string used as a seam in the large central slit. Earlier pictorial restorations made with clumsy haste by carelessly applying black paint to hide imperfections caused by time were also clearly visible.

Burri’s ill-fated work was exhibited at the Galleria Blu in Milan in 1958, then in Brussels with an introduction by Giulio Carlo Argan, who said about the artist, “The matter of a Wols, of a Fautrier, of a Burri is not the formless pile of embers to which life burned by anguish is reduced: since the artist has ceased, in the face of matter, the pride of his own spirituality and has accepted identification, that matter, from the inert past that it was has become memory , has become present and human again [....] the present ’intends’ together the past and the future, binding them in a relationship that is no longer logical, but is all the richer in moral interests: that moral is not only the proposing of a project of action, but also the being present with full awareness of existing and firm decision to do, in the midst of a historical situation.” The exhibition history of the work would continue until 1968, when it disappeared, only to reappear in 2015 for the exhibition Sironi-Burri: an Italian Dialogue, and the curator from the new monograph Alberto Burri Reloaded at Unipol Group’s business museum, CUBO in Bologna, tells how the canvas had been found in a worn condition and extremely torn by time.

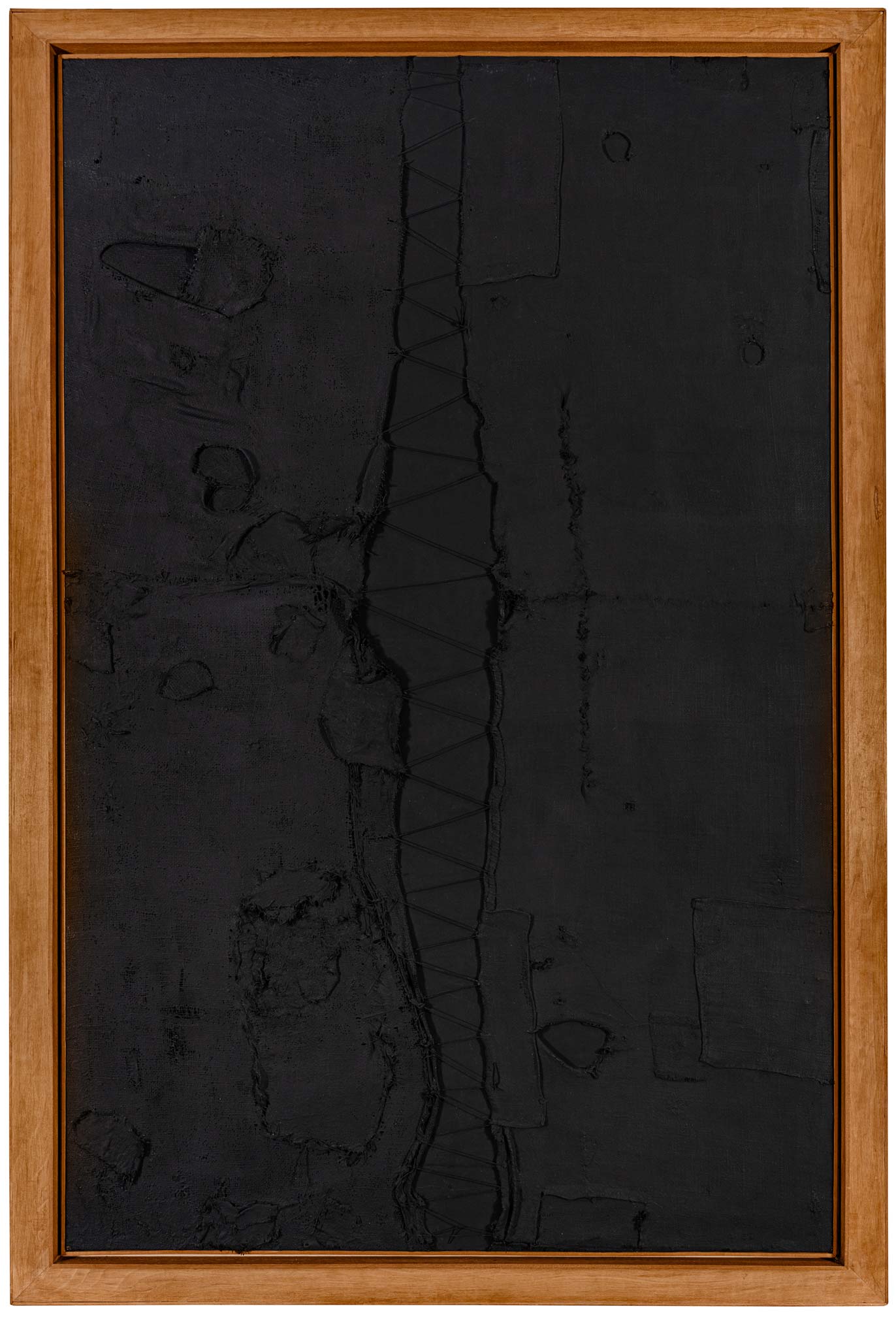

Nero con punti (Black with Dots ) by Alberto Burri is not one of those particularly photogenic works, but that is precisely why it succeeds in fiercely overwhelming the viewer with a palpable, engulfing force. One discovers oneself as a tightrope walker sadly following the geographies of the large canvas, trying not to fall into the central wound, climbing up and down its subtle borders. The 1958 work, totally covered by an opaque black, traps light, placing itself in a fuscum subnigrum that, first with Titian, then with Caravaggio, replaced the white of plaster or stucco in the preparation of works.

“Black,” said philosopher Gilles Deleuze, “is a baroque contribution, with it the picture changes status: things arise from a common background that testifies to their dark nature.” Burri’s blackness is not just a backdrop for the work, but becomes flesh, skin and structure that bends, tears, changes with time, and contrary to other paradigms, one should not try to see beyond that darkness. If Lucio Fontana pierces the canvas allowing space to enter and transform the work into an environment, Burri makes it grow from within with turgescences, ulcers and tears. It is a “monumental work: for its size, for its structure and for the way in which a single color, so charged with valences and history, is entrusted to the textile material that constitutes the framework and integument of the work itself,” writes curator Ilaria Bignotti in the exhibition catalog.

The canvas belongs to those reminiscences of imprisonment in the camp in Hereford, Texas, where Burri began to paint and use the famous War Sacks that carried foodstuffs that, for the artist, were something everyday. Alberto Burri, from a strange and unfriendly land and amid the anguish of imprisonment and homelessness, takes what he finds. He takes the sacks, which become a metaphor for the body and soul at the mercy of the hatred of war. He tears them open, paints and sutures them. Strong and extremely dramatic elements that Burri decided to juxtapose, almost as if to seek a strident contrast, with elements new for his time such as vinavil and polymer paints. And it was above all the variety of materials used that led the restorers down a road little traveled in Europe, leading them to proceed with extreme care and on tiptoe.

The central cut, the very taut string composed of three strands knotted together along the edges, and the deliberately coarse stitching made the painting even more delicate and difficult to approach, contributing to the creation of a more than two-year-long, but sorely needed wait. After removing the environmental dirt that had been created on the surface, the restoration team decided to design carbon fiber “cribs” to carefully lay the stretched cord and finally proceed with the consolidation of the “mat black” paint that was showing tentative lifts in some places. The decision to use funori seaweed was made precisely to protect and accompany the work in its life and subsequent old age by using, as Muriel Vervat explains, “a non-toxic product, defining a peculiar mode of application, respecting both the restoration worker himself and the environment.”

Restoration of

Restoration of Restoration of

Restoration of Restoration of

Restoration ofA new challenge, this one, even for CUBO, which is hosting the free exhibition Alberto Burri Reloaded until January 21, 2023-a venue that has always found itself facing projects of great scientific calibration. The small Bolognese retrospective highlights how the work on display today is not only the result of innovative restoration, but is also the very metaphor of the CUBO space that aims to share interdisciplinary paths, knowledge and new research that can help the future.

The Unipol Group’s enterprise museum on the other hand has intended, in this way, any project by creating a complex range of reflections, questions, new proposals and donating, in this case, the possibility of understanding what is behind a restoration with a long video to accompany Burri’s great work.

The Alberto Burri monograph continues at the CUBO venue in Torre Unipol, Via Larga 8, where four other works of extraordinary stature find refuge: 1950 Tar, 1951 Mold, 1952 Untitled and another 1950 Tar, weaving an ideal dialogue with the great Black with Dots. Protagonists, in this evocative space overlooking Bologna, are the corrugated tars and sands remixed with oils that create new relationships and forms. The smaller 1950’s Tar (60 x 80) accommodates small plastic embryos that stand out against a very intense rubro interrupted only by small shapes now white, now cerulean and yellow. In the larger Tar, the colors are reduced, but the relationship between two- and three-dimensional space increases, creating spaces that deny and override each other, creating a teeming curtain of stimuli in a constant dialogue between shiny and dull.

A different story is told by the Mold of 1951 in which pumice stone mixed with oil is the protagonist and clings, nestles and envelops on the underlying support. But it will be the Untitled of 1952 that will present all the characters present in Black with Dots. Here is the sack, the sand, along with vinavil, collage and stitching that close the ideal dialogue between the five works. A dialogue made up of silences and stitched-up shortcomings.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.