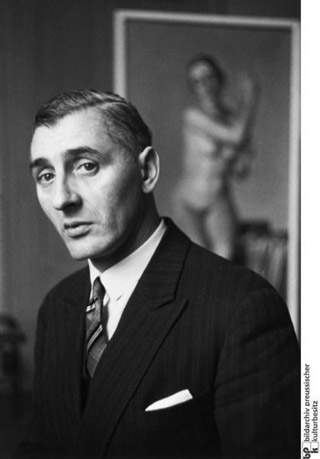

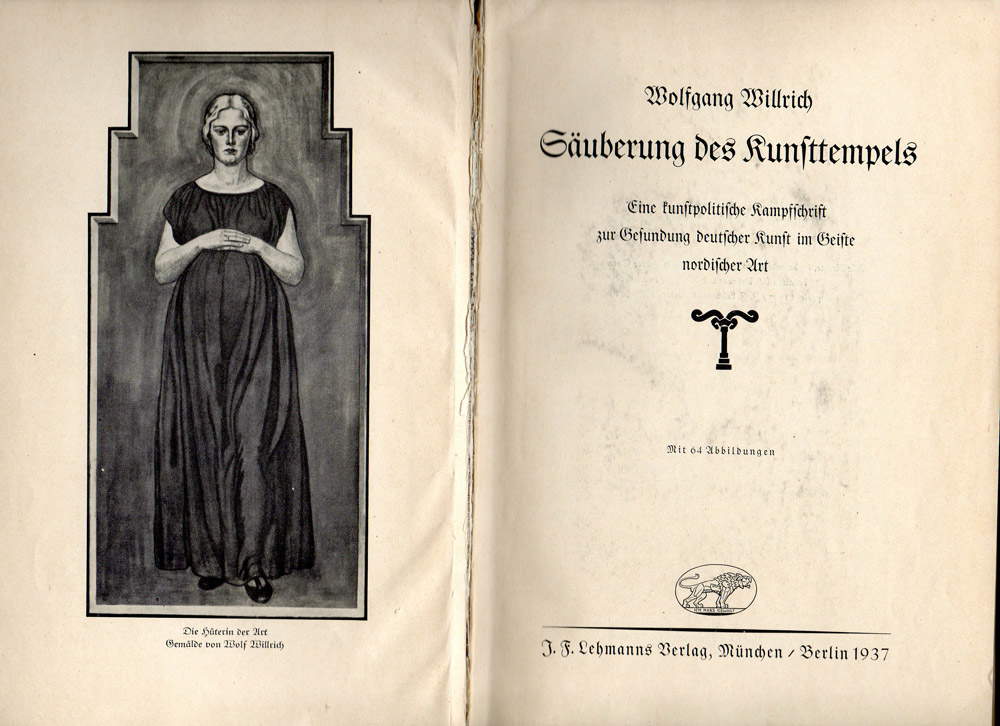

July 19, 1937. An exhibition destined to fill one of the darkest pages in art history opens in Munich at the Hofgarten Institute of Archaeology: the title is Entartete Kunst, “Degenerate Art,” and it is curated by Adolf Ziegler (Bremen, 1892 - Varnhalt, 1959), a tardy and pompous academic painter whom the Nazi regime, in November 1936, put in charge of the Reichskammer der Bildenden Künste (“Reich Chamber for the Visual Arts”), an institute set up to promote German art deemed compliant, but which during the exhibition period was also charged with withdrawing from German museums all paintings that contravened the regime’s own principles. The lines guiding the seizures find their most illustrative compendium in a pamphlet published in early 1937: it is entitled Säuberung des Kunsttempels (“Cleansing of the Temple of Art”) and the author is Wolfgang Willrich (Göttingen, 1897 - 1948), an amateur painter as unrealistic as he is conservative, formerly employed by the Ministry of Culture, and who is given organizational duties for the Munich exhibition.

|

| Adolf Ziegler. Photo: Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz |

|

| The header of Wolfgang Willrich’s book Säuberung des Kunsttempels. |

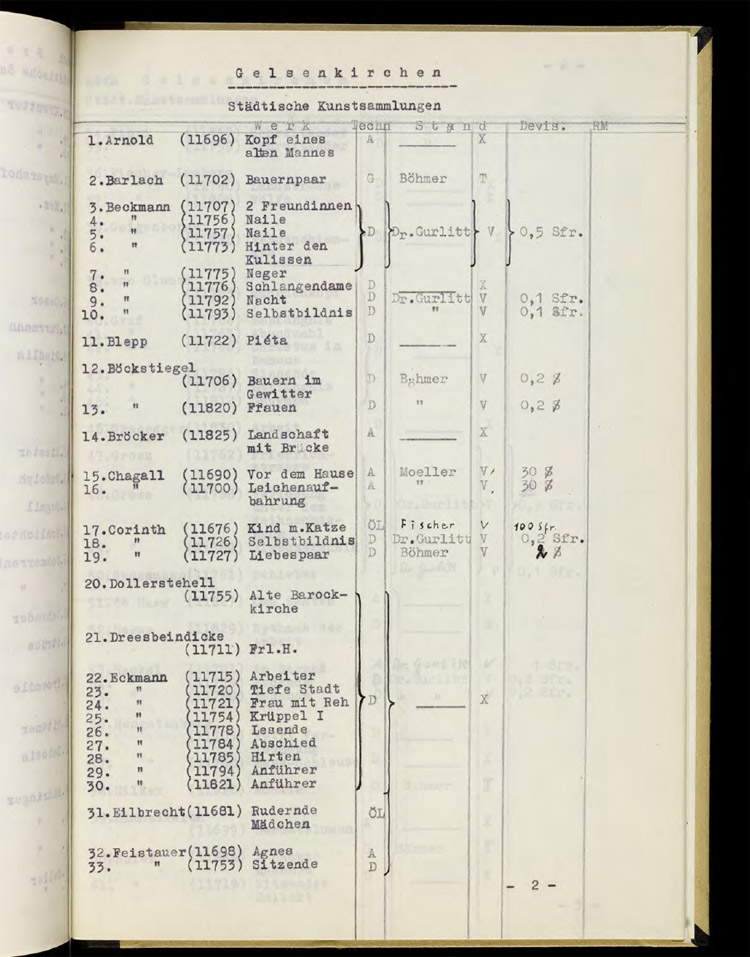

The idea of a “canon of degenerate art” is thus not new: but in the 1930s it was destined to play a profound role in the artistic affairs of Germany and, by extension, all of Europe. In fact, all the most innovative artists of the time (but also authors of previous generations, many of whom have been missing for years) are banned by the regime. The names are illustrious: reading the lists of seized artworks (the only known complete inventory of which is now kept at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London) is like retracing the greatest art history of the early 20th century. We find there the artists of the Die Brücke group (Emil Nolde, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Otto Müller, Max Pechstein, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff among others), those of the Blaue Reiter (Vassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Franz Marc), other expressionists such as Max Beckmann, Marc Chagall and Christian Rohlfs, as well as their forerunners such as Edvard Munch and James Ensor, as well as the artists of the Berlin Secession (such as Oskar Kokoschka, Max Liebermann and Lovis Corinth), those of the Neue Sachlichkeit (George Grosz, Otto Dix, Georg Schrimpf, Conrad Felixmüller), the Dada artists such as Kurt Schwitters and Raoul Hausmann, the Bauhaus artists (Johannes Itten and László Moholy-Nagy, among others) the Cubists (also affected Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Fernand Léger and Oleksandr Archipenko, as well as an Orphic Cubist such as Robert Delaunay), and again, the Futurists(Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà), the Symbolists (such as Gustav Klimt and Odilon Redon), the Post-Impressionists such as Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, and Henri Matisse, and then artists from 1920s Paris such as Amedeo Modigliani and Moïse Kisling, up to the most recent and up-to-date authors, from Piet Mondrian to El Lissitzky via Giorgio De Chirico, Theo van Doesburg, Max Ernst, Natalia Goncharova, and many, many others.

|

| One of the sheets of the inventory works seized (first part of the list of works confiscated from the collections of the city of Gelsenkirchen) |

Many of their works are included in the major exhibition of 1937. An exhibition that, however, is not the first ever: the Munich exhibition is in fact preceded by several other smaller exhibitions, the first of which had been held at the Dresden City Hall in 1933. On that occasion, about two hundred works were offered to the public, two-thirds of which were drawings and watercolors, plus at least forty-two paintings and ten sculptures. Despite its relatively small size, this was an important exhibition, and not only because it was the first of those devoted to “Entartete Kunst,” but also because it formed the founding nucleus of the major event that would open on July 19, 1937. Then, in the four years between the Dresden and Munich exhibitions, events occurred that were destined to have an even heavier and more massive influence on the German art scene. Toward the end of 1936, the Minister of Education and Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, initiates two decisive actions: he appoints, as president of the Reichskammer der Bildenden Kunst, the aforementioned Ziegler, who is decidedly more extremist than his predecessor Eugen Hönig, and above all he outlaws art criticism so as to tighten the Reich’s direct control over every artistic manifestation in Germany (after all, as early as 1929 Hitler had identified the press as one of the main culprits in the spread of “degenerate art”). The decision effectively put the “end” word on artistic debate in the country: from then on, only art that conformed to the Reich’s demands would find a place in galleries. To enshrine the new course and to officially give direction, Goebbels (who, as well as Hitler and Göring, had visited the small exhibitions of “Entartete Kunst” in previous years) decided to organize a double event in Munich: a large exhibition bringing together art considered sound and exemplary(Gro�?e Deutsche Kunstausstellung, “Great Exhibition of German Art”), open to all artists who wish to participate (the judging committee will receive as many as fifteen thousand applications) and an exhibition that, in contrast, will gather what is considered deviant. The latter is organized very quickly: the decree by which Goebbels invests Ziegler with the role of curator is dated June 30. In just two weeks, the Reichskammer president and his commission comb German museums and confiscate 5,328 works, from which those to be shown to the public will be selected.

The directives that Ziegler’s commission follows are quite simple. All works tending toward abstraction or with figures deemed unrealistic are seized. Works considered offensive to common decency, or to the honor of the nation, are then struck. Works by artists deemed lacking in technical skill are then withdrawn from museums. Again, the magazines in which the most up-to-date critics write are reviewed, so that lists of names of artists to be censured are easily obtained. Willrich’s odious book listing additional artists considered degenerate is studied, and the same is done with the literary output of regime critics. In general, all artists whose sensibilities are considered far removed from those of the Reich are affected by the seizures. Even artists who had joined the NSDAP, the Nazi Party, are not spared: Emil Nolde, who had long been a member of the party, has more than a thousand works confiscated, and is forbidden to paint, despite his protests. Nolde, and many other artists, are in fact joined by letters from the Reichskammer president, informing them of their exclusion from the institution. Here is what the one Schmidt-Rottluff received read: "On the occasion of the elimination of degenerate art from museums [...], I inform you that 608 works have been confiscated from you. A number of them were exhibited at the Entartete Kunst exhibitions in Munich, Dortmund and Berlin. For this reason, You must understand that Your works do not conform to the purposes of promoting German culture to the people and to the Reich. You must have been aware of the speech made by the Reich at the opening of the Gro�?e Deutsche Kunstausstellung, and in spite of this even today You are far removed from the cultural thinking of the National Socialist State. On the basis of the above, You are no longer eligible to be a member of this House. [...] I therefore exclude you from the Reichskammer der bildenden Kunst, and prohibit you, with immediate effect, from engaging in any activity, whether in a professional capacity or otherwise, in the field of the visual arts. Signed: Adolf Ziegler."

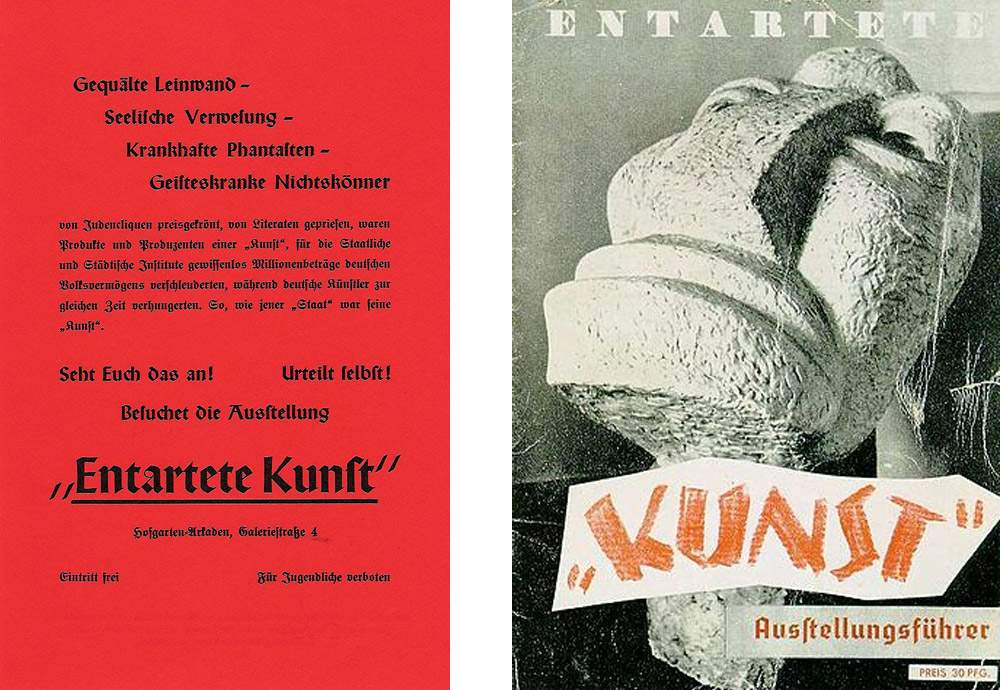

The curators, caught up in the confiscations, have little time to prepare promotional materials. Timing allows them to think only of a flyer advertising the event in this way: Tortured Canvases - Mental Degradation - Sick Fantasies - Incompetent Mentally Ill - Products and producers of an “art” rewarded by the cliques of Jews and appreciated by the literati, bought by the state and cities squandering millions of the national resources while artists of the German people starved. Behold: such was that state, such was its art. Come and see! Judge for yourself! Visit the “Entartete Kunst” exhibition. Free admission. Forbidden for young people. The exhibition’s official catalog will not be published until four months later, on the occasion of the stop the exhibition makes in Berlin, and it becomes famous for its cover, which consists of a photograph of a work by Otto Freundlich (S�?upsk, 1878 Majdanek, 1943), Gro�?er Kopf (Der Neue Mensch), or “Big Head (The New Man),” a primitivist-style sculpture clearly inspired by the large statues on Easter Island: the title of the exhibition is simply affixed to the image. Both Freundlich and his sculpture are, moreover, destined for tragic ends: the sculpture disappears in 1941, probably destroyed, while the artist is deported to the Majdanek concentration camp near Lublin, Poland, and is murdered on the very day of his arrival.

|

| The flyer published to promote the exhibition and the Berlin exhibition catalog. |

The exhibition then opens on July 19: giving the chilling opening speech is Ziegler himself. We reproduce below a passage from his speech: “We still have a tragic duty to perform: we must show the German people that, until recently, certain forces, which saw no natural or clear vital expression in art, exerted a substantial influence on artistic production. They were forces that deliberately renounced a healthy art in order to promote one that was instead sick and degenerate, celebrating it, moreover, as the greatest revelation. But from the words spoken yesterday by the Führer we can eagerly realize that for these art forms the end has finally come. [...] Today we are in the midst of an exhibition that represents nothing more than a fraction of what museums, with the money of the German people, have bought as art and have exhibited and displayed as art. All around you you can see the products of these mad scoundrels, the altered byproducts of impudence, ineptitude, degeneracy. And what the present exhibition has to offer provokes in us the same disgust, the most absolute bewilderment. Many of the curators of our museums do not even have an iota of a sense of responsibility to the people and the nation, which is the basic prerequisite for curating an art exhibition.” Also present at the opening of the Gro�?e Deutsche Kunstausstellung, which had opened the day before, was the Führer himself, who had given the opening speech: however, many of those who were there would later write that, on that day, Adolf Hitler was very nervous. It seemed that, to some extent, he, Goebbels, and the other conventioneers felt the gap in quality between the mostly mediocre and insulting works that populated the Aryan art exhibition, and the works of the most up-to-date avant-garde that had been assembled for the degenerate art exhibition. And Hitler had good reason to be concerned, for the public would prove far more eager to visit the Entartete Kunst exhibition: by the time it closed, set for November 30, the exhibition would register as many as 2,009,899 visitors, more than three times as many as the “great German art exhibition.” It remains to this day one of the most visited art exhibitions in history: for some it is even the most visited contemporary art exhibition ever.

|

| The public waiting in line to enter the Entartete Kunst exhibition in Munich. |

|

| Joseph Goebbels visits the Entartete Kunst exhibition |

|

| Adolf Hitler (second from left) oversees the Munich exhibition with Adolf Ziegler (first from left) |

Several reasons for the success. Free admission certainly facilitated high attendance, but it is but one of the ingredients of such a response that organizers are thinking of further stops, with a view to taking the works of the “degenerate artists” to Berlin, Leipzig, Düsseldorf, Vienna, Salzburg and other Reich cities, in a tour set to last four years. Visitors, meanwhile, perceive the works of “official art” as trite, boring and monotonous, while more stimulation comes from the “degenerates.” Again, the public evidently imagines that the Munich exhibition represents the last chance to see the works of modern artists live and up close: many of them, in fact, will be destroyed, and traces of others will be lost. Or, visitors may wish to see how far the regime has gone in insulting “degenerate artists,” as the flyer suggested.

Indeed, in the exhibition halls, paintings are always accompanied by infamous comments and slogans. The works are many: however, since the Munich edition lacks the official catalog, which, as mentioned above, will be released only on the occasion of the Berlin stop, one can only make estimates of the numbers, and scholars indicate between 650 and 750 works alternating in the rooms of the Hofgarten Institute of Archaeology. We know from the Berlin catalog that the works are divided into thematic groups, each presented by an appropriate title. However, the division of the groups among the rooms, in the Munich exhibition, does not slavishly follow the groupings known from the catalog, but mentioning them nevertheless gives an idea of what characteristics the Nazis ascribed to “degenerate art.” First group, degeneracy ... technique: “Zersetzung des Form und Farbempfindens” (“Disintegration of the perception of form and color”). Second group, works with a religious theme: “Unverschämter Hohn auf jede religiöse Vorstellung” (“Insolent offenses against every religious idea”). Third and fourth groups, works with a political theme: “Der politische Hintergrund der Kunstentartung” (“The Political Context of the Degeneration of Art”) and “Politische Tendenz” (“Political Tendencies”). Fifth group, works considered offensive to morality: “Einblick in die moralische Seite der Kunstentartung: Bordell, Dirnen, Zuhälter” (“Look at the moral aspects of artistic degeneration: brothels, prostitutes, pimps”). Sixth group, works considered detrimental to the dignity of the Aryan race: “Abtötung der letzten Reste jedes Rassebewu�?tseins” (“Destruction of the last remnants of all racial consciousness”). Seventh group, works far from the aesthetic canons considered healthy and in accordance with the Reich’s principles: “Idioten, Kretins, Paralytiker” (“Idiots, Cretins, Paralytics”). Eighth group, works produced by Jewish artists, titled simply “Juden” (“Jews”). Ninth and last group, works by artists considered insane: “Vollendeter Wahnsinn” (“Absolute Madness”).

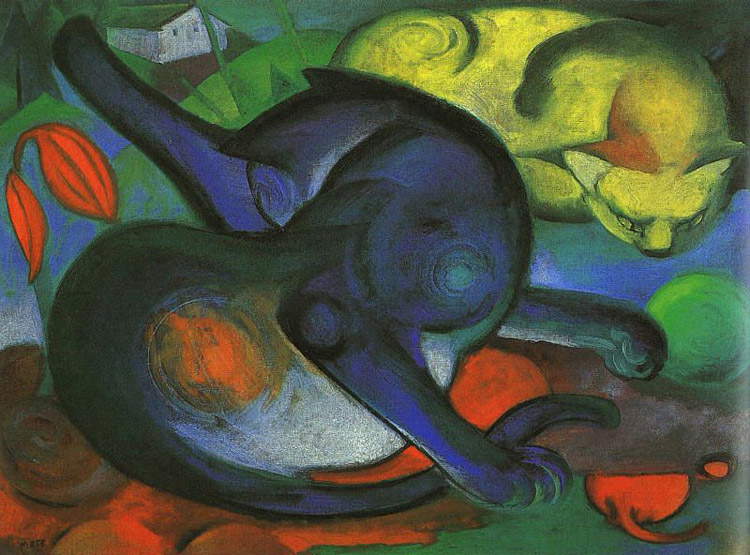

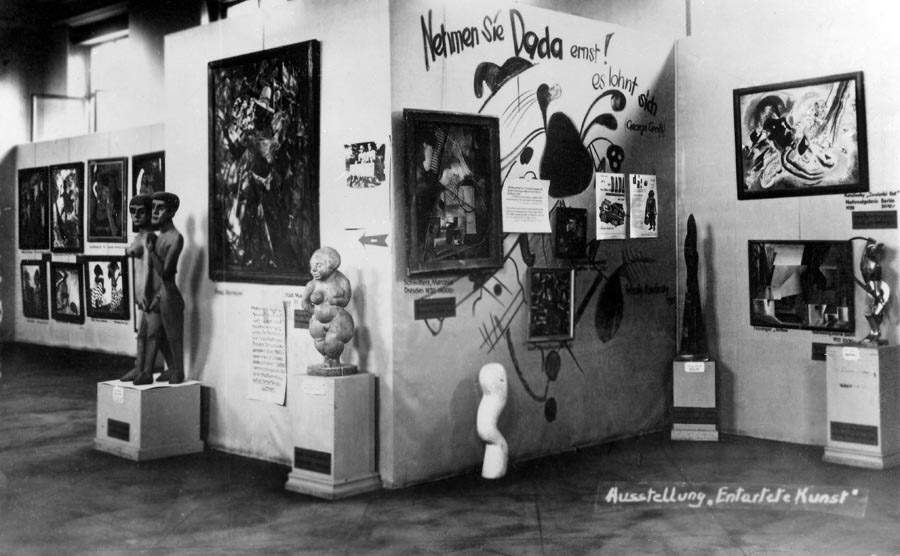

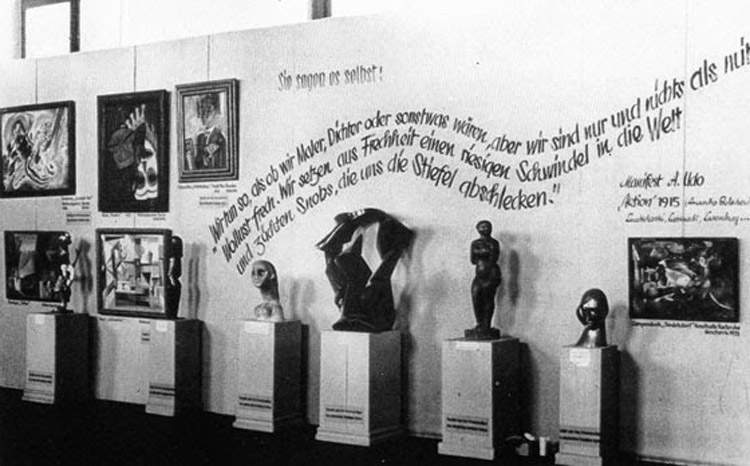

Today we are familiar with many of the works on display at the exhibition, which opens with a large crucifix, tending toward abstraction, by Ludwig Gies, accompanied by the comment “Dieses Schauerwerk hing als Heldenehrenmal in Dom zu Lübeck” (“This hideous work hangs as a tribute to the fallen in Lübeck Cathedral”). The sculpture (later destroyed) introduces the room of religiously themed works, where paintings such as Emil Nolde’s Paradise Lost (now at the Nolde Stiftung Seebüll) or Max Beckmann’s Christ and the Adulteress (now at the City Art Museum in Saint Louis) are featured. But there are many fine works that find their way into the exhibition rooms. Paintings such as Otto Müller’s Three Girls (also now in Saint Louis), Marc Chagall’s so-called Purim (now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art), and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Ladies at the Café (now at the Brücke-Museum in Berlin), Oskar Kokoschka’s View of Monte-Carlo (now at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Liège), Lovis Corinth’sEcce Homo now at the Kunstmuseum Basel, and Franz Marc’s Two Cats, Blue and Yellow (in the same museum). Particularly famous is the wall that houses works pertaining to the Dada movement: in one photograph, under the ironic slogan “Nehmen Sie Dada ernst! / Es lohnt sich” (“Take Dada seriously! / It’s worth it”), a Ringbild by Kurt Schwitters (whose fate we do not know) and Paul Klee’s Legend of the Swamp, which is now in the Städtischen Galerie im Lenbachhaus in Munich, stand out clearly. In another known photograph, we see a wall on which the slogan “Sie sagen es selbst” (“You say it yourself,” addressed to the public) stands and where works such as Emil Nolde’s Masks (now in a private collection), or Vassily Kandinsky’s Two Reds and Conrad Felixmüller’s Self-Portrait, both paintings whose end we ignore, hang.

|

| Ludwig Gies’s crucifix in the exhibition |

|

| Emil Nolde, Paradise Lost (1921; oil on canvas, 106.5 x 157 cm; Seebüll, Nolde Stiftung Seebüll) |

|

| Max Beckmann, Christ and the Adulteress (1917; oil on canvas, 149.2 x 126.7 cm; Saint Louis, Saint Louis Museum of Art) |

|

| Otto Müller, Three Girls (ca. 1920; oil on canvas, 121.9 x 134.8 cm; Saint Louis, Saint Louis Museum of Art) |

|

| Marc Chagall, Purim (1916-197; oil on canvas, 50.5 x 71.9 cm; Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art) |

|

| Oskar Kokoschka, Monte-Carlo (1925; oil on canvas, 73 x 100 cm; Liège, Musée d’Art Moderne et d’Art Contemporain) |

|

| Franz Marc, Two Cats, Blue and Yellow (1912; oil on canvas, 74 �? 98 cm; Basel, Kunstmuseum) |

|

| The wall with the Dada works |

|

| The wall with the slogan “Sie sagen es selbst.” The first three works in the upper left corner are the three by Kandinsky, Nolde and Felixmüller mentioned in the article. |

As of 1941, there will be more than sixteen thousand works confiscated by the Nazis. Many of them will be destroyed, while others, such as some of those listed above, will fortunately manage to be saved. Reading through the list of works on display at the Munich exhibition, one will notice the almost total absence of works by foreign artists (such as van Gogh, Braque, Picasso and others), which had also been seized during the gallery and museum raids. Many of them, in fact, would be sold abroad, often at the initiative of the hierarchs themselves: Hermann Göring, who through confiscation and looting in occupied countries had managed to build up a sizeable collection, had taken a good number of paintings by post-Impressionist artists under his custody in 1938, and had personally sold or bartered them for other works. The Nazis’ measures, however, would not succeed in stopping the avant-garde completely. Many artists would find other ways of expressing themselves: most would move abroad and continue their activities in France, Holland, the United States, continuing their work where seizures and destruction had interrupted it. And today it is safe to say that, despite the dark interlude, art proved to be decidedly stronger than violent barbarism.

Reference bibliography

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.