Elles: the Parisian prostitutes according to Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

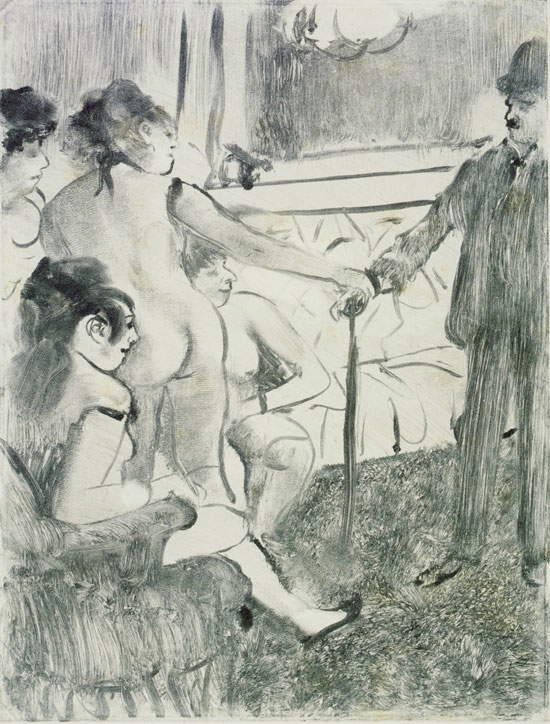

The great Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (Albi, 1864 - Saint-André-du-Bois, 1901), as is well known, was a frequent visitor to the brothels of late 19th-century Paris. In recent times we have seen a renewed interest in this important artist, an interest embodied in several exhibitions that have never failed to address the relationship between Toulouse-Lautrec and the prostitutes who worked in the brothels known to him. However, recent exhibitions have often proposed superficial reinterpretations of that relationship, without delving into the motivations that had led the painter to approach a world that, although already the object of attention by many artists, was being analyzed by Toulouse-Lautrec with an entirely new eye. An artist such as Edgar Degas, author of a series of monotypes depicting scenes of Parisian brothel life, had probed the environment of the maisons closes in an almost detached way, giving an account of the situations that arose within the premises: bored prostitutes waiting for clients, compassionate (and awkward) gentlemen, smartly dressed in suits and ties, who are almost dragged by the already naked harlots, women with bodies now no longer in the prime of youth lying on the brothel’s couches in vulgar and disheveled poses to better show themselves to the clientele.

|

| Edgar Degas, The Serious Customer (c. 1876-1877; black ink monotype on paper, 21 x 16 cm; Ottawa, Musée des Beaux-Arts du Canada) |

Degas wanted, in essence, to show the viewer the boredom of the work of prostitutes, the total lack of sensuality (as well as, of course, refinement), and the commodification of the body, not without, however, feeling a little compassion for the fate of these women, however much his monotypes were nonetheless imbued with an irony that was directed at both the prostitutes and their clients. Toulouse-Lautrec’s approach is totally different. It is well known that a bone disease had impaired the normal development of his lower limbs, causing the artist to go no further than a stature of five feet, five inches. Therefore, although he continued to maintain relations with his family (especially his mother), around the age of twenty-five he decided to remove himself from the aristocratic milieu he had frequented during his childhood (his family was in fact noble) and retreat to Montmartre, to the slums of society. He had thus begun to frequent brothels to find the human warmth of which we can imagine he had begun to miss as his illness progressed. And in one of those brothels, the one located at 8 rue d’Amboise, the painter had set up his residence in 1892.

Within the walls of the brothel, Toulouse-Lautrec felt at home. It is said that, shortly after settling in the maison close, he had commented “j’ai enfin trouvé des femmes à ma taille,” “I have finally found women of my stature”: quite clearly, the artist was feeling the weight of his disability. Toulouse-Lautrec felt a kind of correspondence between his condition and that of the prostitutes, and probably thought that only among people on the margins of society were there prerequisites for being understood (and for understanding, in turn, the mostly sad and squalid lives of prostitutes). And indeed, between Toulouse-Lautrec and the prostitutes of the maisons closes in which he lived, a relationship of mutual understanding, disinterested friendship, genuine closeness was established. The cabaret singer Yvette Guilbert (Paris, 1865 - Aix-en-Provence, 1944), portrayed several times by Tolouse-Lautrec, in her memoirs recounted the relationship between the artist and the prostitutes in these terms: “Il me dit son goût de vivre dans la maison close, d’y regarder palpiter la prostitution et d’y pénétrer les douleurs sentimentales des pauvres créatures, fonctionnaires de l’amour. Il est leur ami, leur conseiller parfois, jamais leur juge, leur consolateur, bien plutôt leur frère de miséricorde” (“He told me the taste of his living inside the closed house, of seeing prostitution palpitate and understanding the sentimental pains of those poor creatures, servants of love. He was their friend, sometimes even their confidant, but never their judge, their comforter ... rather he was for them like a brother in compassion.”).

|

| Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Portrait of a Girl (c. 1892; oil on canvas, 27.3 x 23 cm; Brisbane, Queensland Art Gallery) |

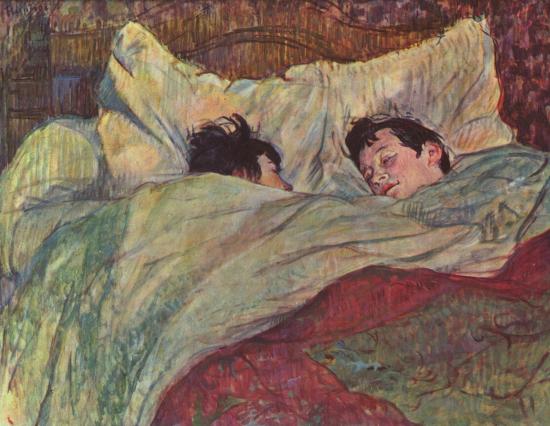

Toulouse-Lautrec also had the opportunity to paint for the house of tolerance on the rue d’Amboise: in fact, the maîtresse, Blanche d’Egmont had entrusted him with the task of making portraits of the girls in the house, which would be used to decorate the brothel’s rooms (in particular, they would be placed in the main salon). Sixteen portraits were thus born, in profile, inscribed in medallions in the French portrait tradition-a deliberately magniloquent language for a place where the flesh of young girls was available for a fee. At the same time, the artist was attracted to the lives of prostitutes, to the point that he wanted to depict in some canvases and tablets the intimate moments of the girls, who were often capable of having real amorous feelings for each other, as Toulouse-Lautrec testifies in works such as Le lit or Le baiser, which show us some of the rare moments of happiness that the young women found after days of work aimed at satisfying the sexual appetites of the many Parisians who frequented the maison close. The substantial difference between Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec lies in the fact that Degas had confined himself to frequenting brothels, while Toulouse-Lautrec lived within them: the distance between the works of the two artists is therefore abysmal, because Toulouse-Lautrec was, we may say, emotionally involved.

|

| Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Le lit, “The Bed” (c. 1892; oil on cardboard, 71 x 87 cm; Paris, Musée d’Orsay) |

Toulouse-Lautrec would later show his tablets with the maison close scenes in a few exhibitions, but their fate was to remain confined to private collections. However, the artist developed his ideas in what is perhaps the best known of his works on the theme of meretriciousness in late 19th-century Paris: the Elles collection, a series of lithographs depicting prostitutes in some Parisian brothels in the midst of their daily routine, and which the artist published in 1896. It was a collection of ten color plates (plus a frontispiece) that were reminiscent, in style, of the Japanese prints so much in vogue at the time and that influenced a large number of artists (including Vincent van Gogh, who felt the appeal of this type of artistic expression in a decisive way), but which did not achieve any commercial success: Gustave Pellet, the publisher, probably hoped to achieve the same success he had achieved with other series of erotic prints, but the intent failed perhaps precisely because Toulouse-Lautrec’s lithographs had nothing pornographic about them, nor were they intended to inspire sensuality and eroticism. The cover itself, on which the title and the typical monogram with which Toulouse-Lautrec signed his works appear, can be seen as a kind of statement of intent: the artist depicts a prostitute, covered by a long robe, as she in a completely natural gesture undoes her hair and prepares to receive a client, whose presence is suggested by the top hat resting, along with a piece of underwear, on top of a clothes rack. The eroticism, if there is any, is only suggested, and it is in any case a routine and listless eroticism, in no way fueled by passion.

|

| Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Frontispiece for Elles (1896; color ink lithograph on paper, 57.8 x 46.6 cm; private collection) |

|

| Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Femme en corset - Conquête de passage, “Woman in corset - Conquest of passage” (1896; color ink lithograph on paper, 52.5 x 40.5 cm; private collection) |

The man, in the entire series, appears only once: in the ninth sheet, titled Femme en corset - Conquête de passage (“Woman in corset - Conquest of passage”). But it is nonetheless an anomalous presence compared to what we would expect from a brothel scene: the two figures, that of the prostitute and her richly attired client (members of the aristocracy and upper middle class were in fact also used to visit maisons closes), are distant, do not speak to each other, do not establish human contact. Both of them, on the contrary, seem bored, give the impression of participating in a tired, customary ritual devoid of any emotion and any involvement: lacking, in essence, passion, on the part of both of them. And the little picture, which we see on the left, depicting a satyr undermining a nymph (typical of such establishments) can therefore be of no use: its intent to arouse the customers is rendered futile by the total absence of transport that characterizes Toulouse-Lautrec’s print.

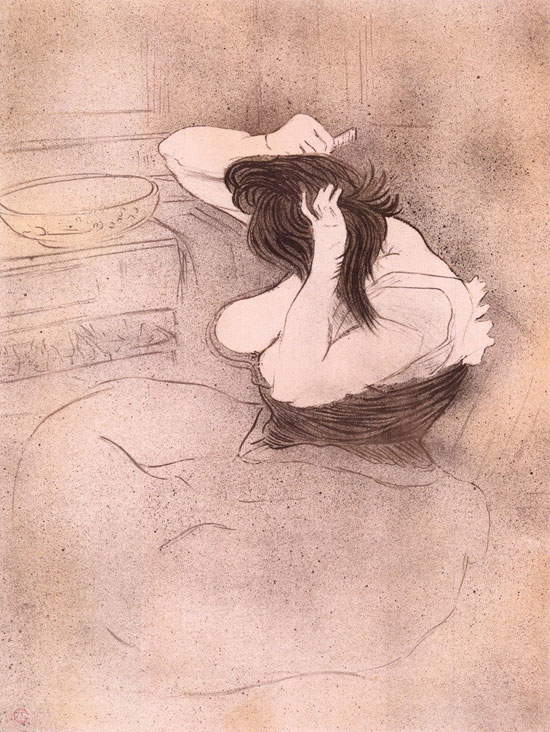

We are faced with scenes that seem pervaded by a melancholic resignation: the girls are forced to exercise a profession that relegates them to the margins of society, and they can only find relief from their condition in moments of intimacy, which become the real protagonists of the Elles series. The girls virtually never appear nude, and perhaps for this reason, too, the series was a commercial failure, since the publisher, as mentioned, had attempted to target it to an audience that was regular consumers of erotic prints. Conversely, the female workers of the brothel are depicted in the quiet moments of their everyday life: in the third sheet(Femme couchée - Réveil, “Woman lying down - awakening”) a girl, lying on her bed and still under the covers, although she has already woken up hugs her pillow as if to communicate that she has no desire to get up, while in the sixth sheet(Femme à la glace, “Woman in the mirror”), we can see a woman as she mirrors herself after getting up (the slippers at the foot of the bed, the nightgown with one strap down, and the disheveled hair eloquently tell us what time of day it is), and again in the seventh sheet(Femme qui se peigne - La coiffure, “Woman who combs her hair - The hairstyle”) we see another one intent on styling her hair before receiving a client.

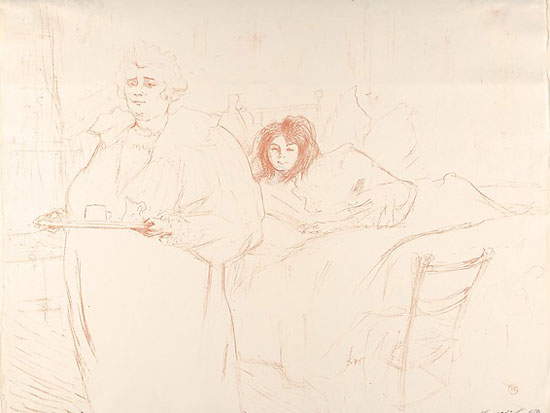

Toulouse-Lautrec’s women, sometimes young but often no longer in the prime of life, are depicted without the slightest erotic ambition, and also without any moralizing intent: the artist simply intends to recount their life in the brothel. In short, spontaneity prevails. It will come as no surprise, therefore, if the second sheet(Femme au plateau - Petit déjeuner, “Woman with tray - Breakfast”) offers us a scene in which the maîtresse of the house on rue des Moulins (where the painter settled after leaving the maison on rue d’Amboise), Juliette Baron, takes the breakfast tray away from the bed of her daughter Pauline (known in the milieu by her diminutive, Mademoiselle Popo), who has just consumed it before starting a new day of work in the brothel run by her mother.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, with his Elles series, wanted to take the viewer on an unusual journey, far from the limelight, far from the sensuality of the works of many of his colleagues, far from the fashionable clubs, elegant dinners, and carefree parties that also appear in many contemporary works of art and that, thinking of late 19th-century Paris, are now part of the collective imagination. Toulouse-Lautrec wanted to show us the saddest face of this world: a face that reminds us how behind the smiles and cheerfulness were very often hidden the stories of fragile women, forced to sell themselves for a living, used only as objects, never worthy of a friendly look or a sweet word. In front of Toulouse-Lautrec’s lithographs, therefore, it becomes difficult not to feel some compassion for “those poor creatures” who had found in the artist one of their rare friends, and one of the even rarer men capable of feeling sincere feelings toward them.

|

| Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Femme couchée - Réveil, “Reclining Woman - Awakening” (1896; color ink lithograph on paper, 40.5 x 52.5 cm; private collection) |

|

| Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Femme à la glace, “Woman in the Mirror” (1896; color ink lithograph on paper, 52.5 x 40.5 cm; private collection) |

|

| Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Femme qui se peigne - La coiffure, “Woman combing her hair - The coiffure” (1896; color ink lithograph on paper, 52.5 x 40.5 cm; private collection) |

|

| Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Femme au plateau - Petit déjeuner, “Woman with Tray - Breakfast” (1896; color ink lithograph on paper, 40.5 x 52.5 cm; private collection) |

Reference bibliography

- Sarah Suzuki (ed.), The Paris of Toulouse-Lautrec: Prints and Posters, exhibition catalog (New York, MoMA, July 26, 2014 - March 22, 2015), The Museum of Modern Art of New York, 2014

- Jane Kinsman, Michael Pantazzi (eds.), Degas: The Uncontested Master, exhibition catalog (Canberra, National Gallery of Australia, December 12, 2008 - March 22, 2009), National Gallery of Australia Publ., 2008

- Florence Rionnet (ed.), Les nuits de Toulouse-Lautrec: de la scène aux boudoirs, exhibition catalog (Dinan, Musée de la Ville, July 7 - September 20, 2007), Somogy, 2007

- Rossana Bossaglia, Tulliola Sparagni, Danièle Devynck (eds.), Le donne di Toulouse-Lautrec, exhibition catalog (Milan, Fondazione Mazzotta, October 14, 2001 - January 27, 2002), Mazzotta, 2001

- Pierre Mac Orlan, Toulouse-Lautrec: peintre de la lumière froide, Editions Complexe, 1992

- Suzanne Grano, Caroline Turner, Michel Sourgnes, Toulouse-Lautrec: Prints and Posters from the Bibliothèque Nationale, Wittenborn Art Books, 1991

- Charles Bernheimer, Degas’s Brothels: Voyeurism and Ideology in Representations, no. 20, 1987, pp. 158-186

- Riva Castleman, Wolfgang Wittrock (eds.), Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec: images of the 1890’s, The Museum of Modern Art of New York, 1985

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.