Elin Danielson Gambogi, the story of a painter against convention between Finland and Italy

Art history is a male domain of mastery: a peaceful consideration that few would question. After all, in a purely male-dominated world it could not have been otherwise, so much so that only in relatively recent times has the role of women in the art world finally come into focus. In the past it was not impossible for women to practice art, but social dynamics related to a role of subalternity made it difficult, particularly when they had the audacity not to limit art to a bourgeois pastime but intended to turn it into a profession.

The first, few exceptional figures who managed to crack this oppressive cage of conventions, such as the well-known Lavinia Fontana, Elisabetta Sirani, Sofonisba Anguissola, Artemisia Gentileschi, and Plautilla Bricci, nevertheless had to clash with a world that, as its only yardstick, had men’s. These and not many other female colleagues managed to attract a fair amount of interest in them from their contemporaries, but this more often than not did not prove sufficient for them to overcome even the resistance of the persistence in later centuries of a sexist view. In fact, therefore, even those who were able to emerge and distinguish themselves in life were not infrequently soon omitted from art history. Fortunately, our contemporaneity, in parallel with what has happened in other fields as well, has recovered some important names of women artists. Other notable personalities, however, are still waiting to be rediscovered, among them Elin Danielson Gambogi.

That of the Finnish artist, born Elin Kleopatra Danielson (Noormarku, 1861 - Antignano, 1919) is the story of a great cosmopolitan painter, played out when it was still neither easy nor advantageous for a woman to take up this profession, just as her choice to travel the world must certainly have been bizarre to her contemporaries. The painter then was aware of her role as a woman, so much so that she broke the conventions of that period even with her painting.

Danielson Gambogi’s story is then enriched by extraordinary encounters, such as those with Jules Bastien-Lepage and Auguste Rodin, and divided between the teachings of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes and Giovanni Fattori. But it is also the story of the poignant love between her and her husband, the Leghorn-born and post-macchiaiolo Raffaello Gambogi (Leghorn, 1874 - 1943), which plays out between the glacial Finnish landscapes and the sunny ravines of the rocky Leghorn coast, events that are not just futile gossip but that determine fundamental outcomes for the painting of both spouses.

Yet, even today, Danielson Gambogi’s is a name decidedly little known to the general public, although in his lifetime he did not fail to win much praise and participation in major exhibitions. After her death, her name fell into total oblivion: being missed in Italy far from her native country in an era of nationalism deprived her of the justly timely tribute from her homeland, Finland, while her adoptive country was equally eager for attention. We can hypothesize several reasons for this: the insistence of a strongly male-centric criticism that already in her lifetime had often lumped her wife with her husband Raphael certainly concurred, a situation that was partly justifiable by the affinities between the two artists’ painting, often driven almost to mimesis, and on the other hand the lack of interest that involved all Italian painting at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. The silence around Danielson was broken only in recent decades, when some research in Finland and a few Italian studies partially reconstructed the biography of this extraordinary figure. It is therefore worthwhile to briefly review the incredible life and artistic experience of Elin Danielson.

Born in Noormarkku, a small country village in western Finland, to a wealthy landed middle-class family, her life was turned upside down at a very young age when in 1872 her father took his own life following a business failure. Growing up with her mother and sister, she began her artistic training early, and at the age of fifteen she attended the Helsinki Academy of Fine Arts, thanks to the financial support of a prominent family in her hometown who supported her for a long time. She later furthered her education by taking a course in painting on ceramics, and Adolf von Becker ’s Private Academy of Art, which instilled her in naturalist painting. Thanks to a check given to her by the Senate, she undertook a study trip to Paris in 1883, where she attended the prestigious Colarossi Academy receiving instruction from Gustave Courtois, and then at the atelier of Auguste Rodin. The French capital offered her an innumerable amount of intoxicating stimuli compared to the isolated Helsinki; here she began to practice outdoors in gardens, making small and very rapid studies from life, connoted by an Impressionist matrix, as in the painting Luxembourg Garden.

Instead, he spent his summers in Brittany, in search of a more genuine and unspoiled rural landscape, where he made the acquaintance of Jules Bastien-Lepage, who had long depicted the daily life of Breton peasants. The French artist was always a reference for Danielson, who was suspended between a solid, naturalistic drawing facility and an impressionistic freshness. In Brittany the Finnish artist immersed herself in en plein-air painting, and tempered her ability to probe and render luministic data. From this period is the painting Breton Girl, oriented on the lesson of Lepage, in a play of strong contrasts played out between black and white.

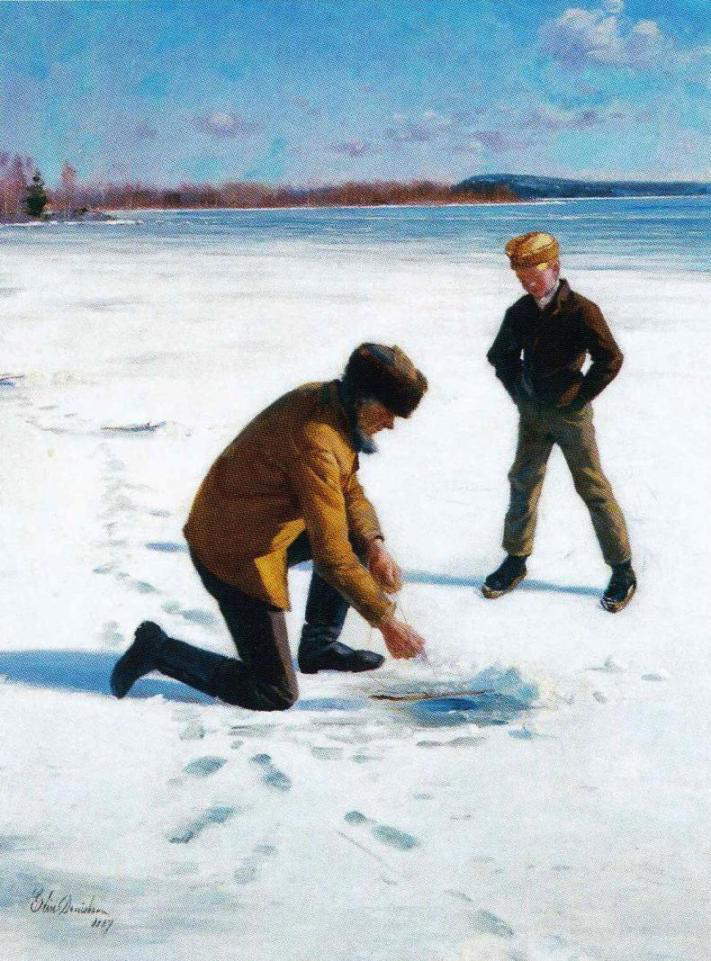

For just over a decade the Finnish artist’s life was divided between her homeland and France. In Finland Danielson took part in the colony of artists settled in theAland archipelago, painters who shared an interest in naturalistic outcomes in painting and advocates of the en plein-air technique. The latter promoted a new interest in Finnish landscape and nature, investigated in its Romantic sense of mysterious and terrible power. Danielson turned instead to the people living around them, portrayed during strenuous farm work. The painting The Winter Peach shows a pictorial piece of intense verista quality with effects of fine poetry, given by the icy Scandinavian light that illuminates the snow and reflects on the ice.

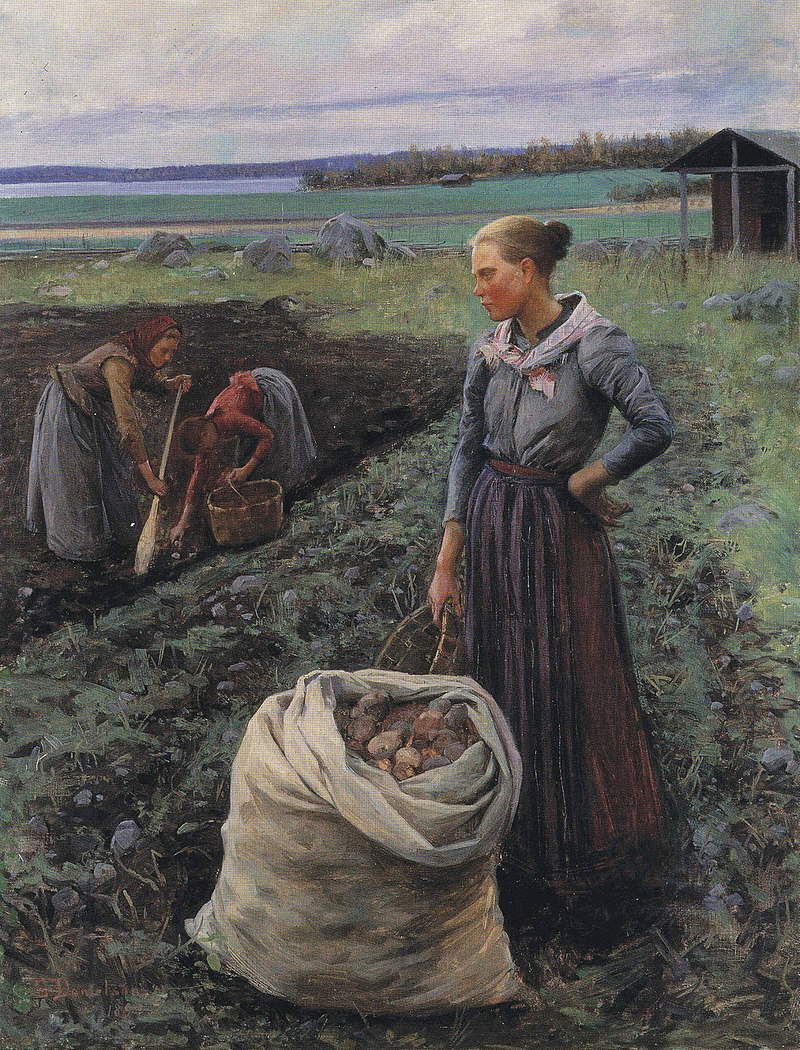

In Paris, however, she continued her studies and in 1889 became a student of the famous Symbolist painter Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. Elin Danielson was a cosmopolitan and unconventional woman, with a lifestyle that her time deemed unbecoming, but then again, the painter must have been particularly intolerant of these social impositions, and this is also evidenced by the painting to which she gave life during these years. “Elin’s artistic production is a kind of hymn to women and their dignity,” writes Giovanna Bacci di Capaci, and indeed the Finnish artist seems to claim, through her canvases, the emancipation of women. She creates works where female figures are the absolute protagonists, caught during moments of hard work or of leisurely intimacy, they are strong and determined subjects. These are perhaps the most iconic and original paintings of his production, such as Potato Harvesters, in which female field workers acquire monumental dignity, while The Portrait of Hilma Westerholm won a medal at the 1889 Paris World’s Fair. But there are other paintings that were considered unseemly at the time, these show eternalized women in poses or attitudes deemed unseemly, such as Finished Breakfast: in a meticulously described interior, a woman, probably Elin’s sister, is caught absorbed in her thoughts (some in recent times have speculated with a hangover) while in an extremely natural manner smoking a cigarette, resting on the table, on which a freshly eaten meal is laid out and a still lit cigarette resting on the tablecloth, alluding to the presence of a person in her company. Perhaps what scandalized contemporaries the most, as proposed by Bacci di Capaci, is the fact that the woman was taking a moment for herself, instead of tidying up the table, as per her duty.

There followed years of exhibitions in Finland, work, and important encounters and acquaintances, such as a love affair with Norwegian sculptor Gustav Vigeland that lasted several years, and a friendship with the well-known painter Akseli Gallen-Kallela. It was on the latter’s advice that Danielson decided to visit the Belpaese: “It must be one of your countries, this Italy,” the Finnish artist wrote to her. In 1895 the painter then spent three months between Rome and Florence, returning there in January of the following year to attend the Scuola di Nudo in Florence. Here it is likely that she also studied with Giovanni Fattori, and at his lessons she met one of his faithful pupils, the Leghorn-born Raffaello Gambogi, a young painter who had distinguished himself a few years earlier with the iconic canvas Gli emigranti, now in the Fattori Museum in Leghorn. Soon the acquaintance between the two matured into a love affair, despite the fact that Raphael was thirteen years younger than Elin, further evidence that the painter was uncaring about the morals of the time.

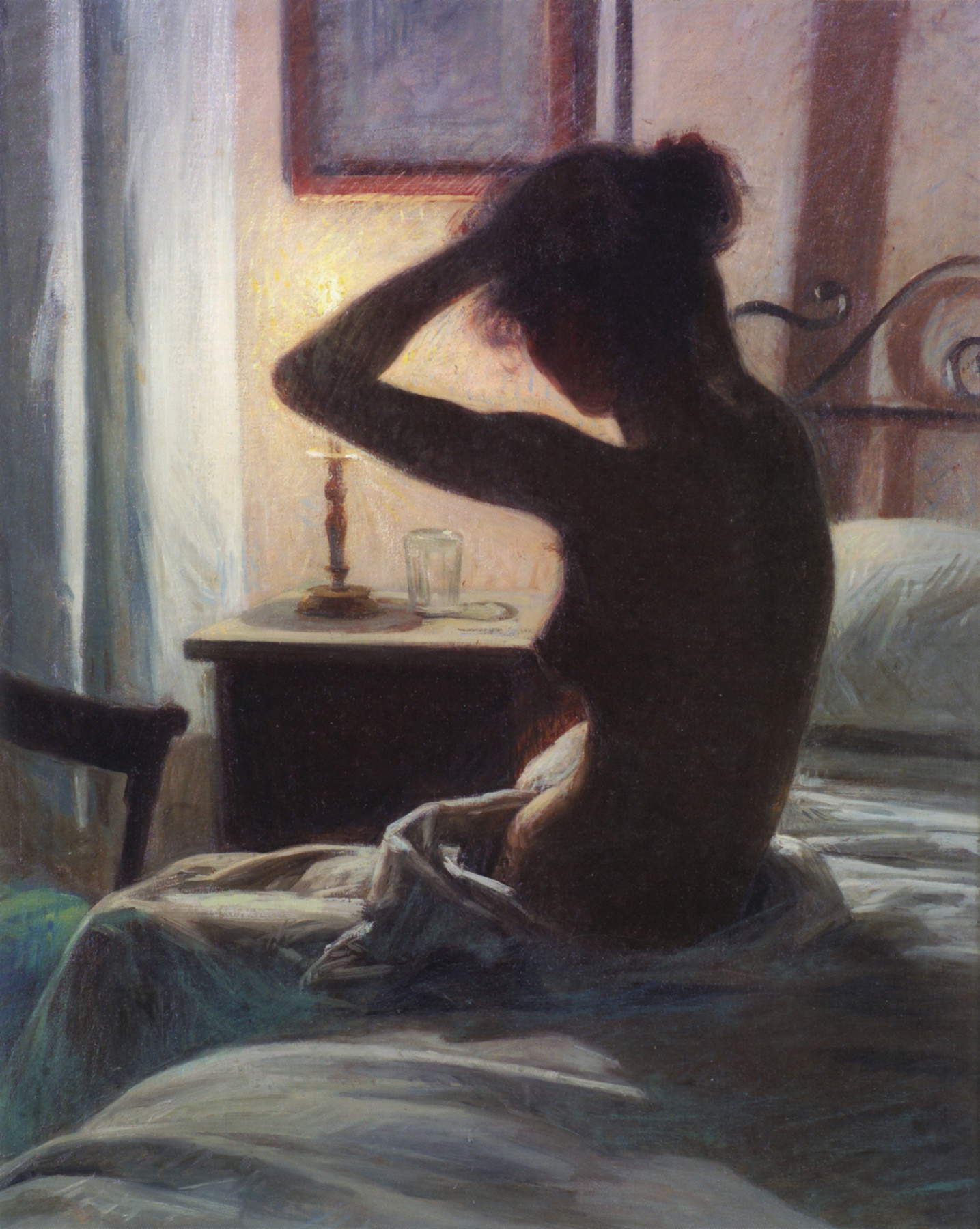

It was during these years that Elin Danielson produced the last paintings, known to date, that give such an unconventional reading of the figure of women, such as The Maid, At Rest and In the Morning, where, for example, an undone marriage bed is seen, an obvious reference to sex. These are paintings of great intensity in which the focus is on the luministic side in its different gradients within a domestic space.

As her relationship with Gambogi intensified, her marriage celebrated in 1898 and her subsequent final move to Italy, Elin would no longer produce paintings with scandalous content, a renunciation dictated perhaps by her new role as a married woman or by the strongly conservative customs of her adopted homeland. The newly formed family of artists, after an initial stint in Antignano, near Livorno, moved to Torre del Lago, where the two were part of the La Bohème Club formed around Giacomo Puccini and attended by the likes of Plinio Nomellini, Angiolo and Ludovico Tommasi, Francesco Fanelli, and Ferruccio Pagni. The shores of the lake and the mountains became the subject of the Finnish artist’s paintings: they are paintings of bloodless paint and cold tones, with figures and landscapes emerging from a kind of haze, as in the painting Girl Rowing.

The stay in Torre del Lago did not last long, and as early as 1899 the Gambogi returned to Antignano on the advice of a doctor, as Danielson fell ill, and the lake’s humid climate was considered harmful. Back in Livorno, the sea and country landscapes once again burst onto Elin Danielson Gambogi’s canvases, views bathed in a warm Mediterranean light that again made the vision crystal clear and the colors vivid. The painter, without great difficulty managed to adapt her painting forged on French naturalism, toward Macchiaioli poetics.

Life in the Gambogi family was characterized as a true artistic symbiosis: in fact, several paintings by both artists with the same subject matter and practically identical compositional solutions are known. Although, as Anna Franchi wrote of them, the couple had “the fault of resembling each other a little too much in their search for effects, however much stronger Ella seems to me.” The themes that interested Elin Danielson at this time were more and more rarely interiors, replaced by glimpses of the coast, unspoiled landscapes or even the work of the fields, where often the protagonists continue to be women, but no longer proposed in their unconventional aspects. These are works reread as much through the lesson of the Frenchman Jean-François Millet as of the Tuscan Egisto Ferroni.

The cohabitation of the two, however, also recorded nefarious moments, given by the infidelity of Raphael, who in 1901 fell in love and consummated a romance with Dora Wahlroos, a Finnish painter who had arrived in Antignano to find her old friend. A deep crisis began between the two, which only her self-sacrifice allowed them to overcome: “If the bonds that unite us were not so strong and the harmony in our work, which almost corresponds to a child, this catastrophe would surely have led us to separation.”

The two also attempted to reestablish the relationship through a trip to Finland, but unfortunately some psychological problems arose for Raffello, who was suffering from a nervous breakdown. Elin, no longer able to sustain the situation and deprived of time to devote to her art, decided to leave her husband and return to her own country, albeit not without difficulty, since at the time her husband’s signature was obligatory on her passport, which he refused to affix.

He stayed in Finland for almost a year, then returned to Italy to Venice. But Raphael’s health and condition worried her so much that she decided to return to his side. And she stayed with him even when from 1905 they had to move to Volterra, where a major psychiatric hospital was located, in search of treatment for the neurasthenia that afflicted Gambogi.

Despite the many difficulties Danielson decided to always remain close to her husband, sacrificing her artistic interests as well. She worked constantly to try to sell the Leghorn’s works, even in Finland, although she was agreed to be a more talented and accomplished painter than her husband.

Although confined to secondary artistic centers, the Finnish artist was able to enjoy significant success: the painting Estate was purchased by King Umberto I, while Interno entered the collections of the Gallery of Modern Art in the Pitti Palace, and for a time it seemed almost possible that one of her self-portraits would enter the Uffizi Gallery, a project that unfortunately did not materialize in the end. She was also the first Finnish artist to participate in the Venice Biennale, although she exhibited with the Italians. In 1900 she won a bronze medal at theUniversal Exhibition in Paris, and continued to exhibit regularly in her native country, which today holds several of her works in important museum collections. On December 31, 1919, Elin Danielson died prematurely in Antignano, throwing her husband into a deep state of despondency from which he would never recover.

The name of this "gentle flower of the North transplanted in the garden of Italy," as the plaque on the tomb where Danielson rests with Gambogi in Livorno reads, ended up in oblivion, and the Italian milieu was not grateful to her, so much so that later in not a few paintings her signature was erased to replace it with that of her husband, whose estimates did not reach mind-boggling figures anyway. Today, following a number of exhibitions including Elin Danielson Gambogi. A Woman in Painting curated by Giovanni Bacci di Capaci and Elin Danielson-Gambogi - In the Italian Light curated by Virve Heininen, the spotlight has been turned back on her artistic experience, and thanks to the revived attention of her native country, she has also been the subject of renewed market interest. Unfortunately, in Italy, Elin Danielson’s name still remains rather obscure, also complicit in the scarcity of her works present and exhibited in public collections, but we hope that this reborn interest in distinguished women in art will soon lead to a just recovery of a leading artist who elected Italy as her adopted home.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.