We anticipate the essay by Maurizio Cecchetti that appears in the catalog of the exhibition conceived by Vittorio Sgarbi Art and Fascism currently running at the Mart in Rovereto, curated by Beatrice Avanzi and Daniela Ferrari, until September 1. The volume is published by L’Erma di Bretschneider, whom we thank for their kind permission.

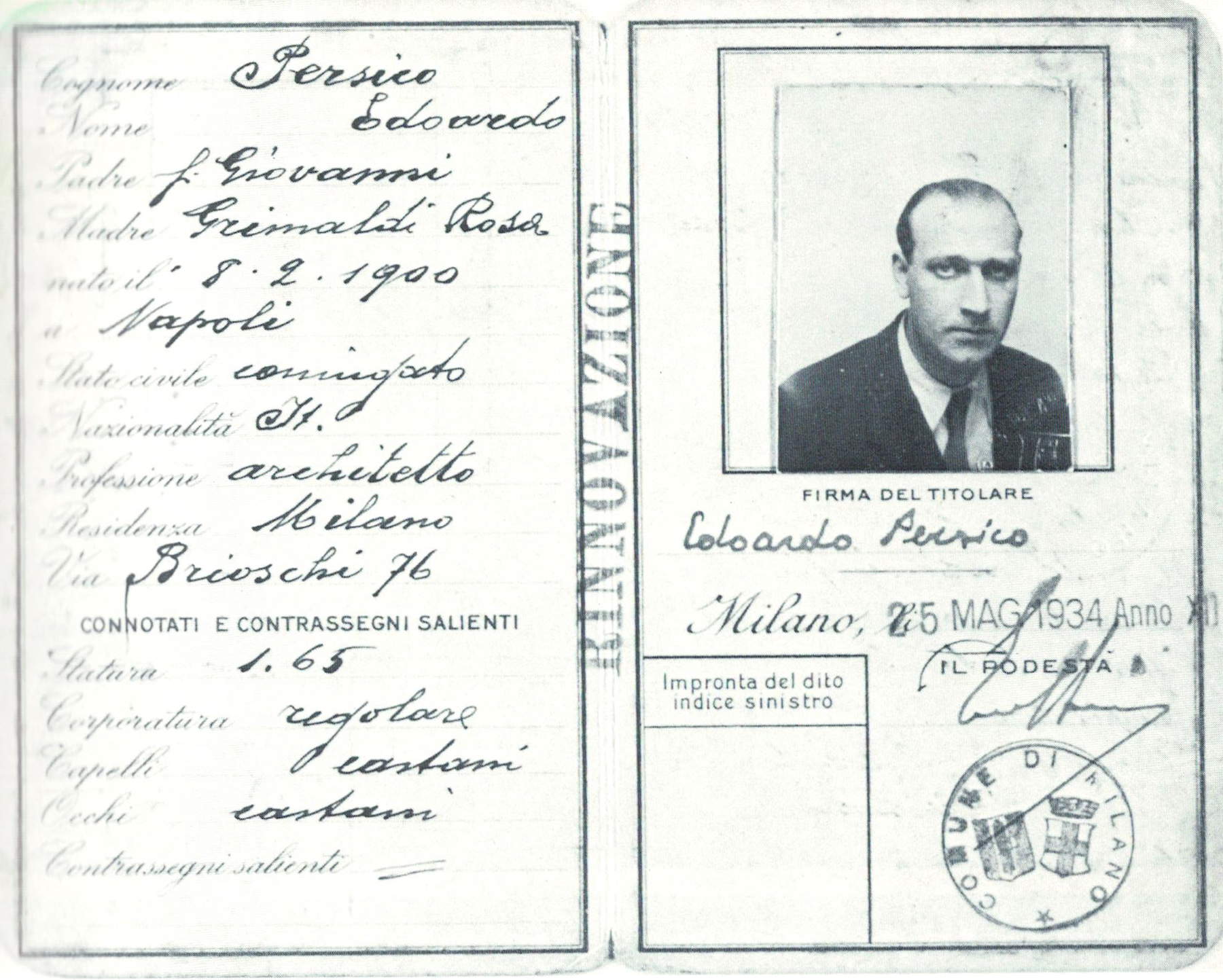

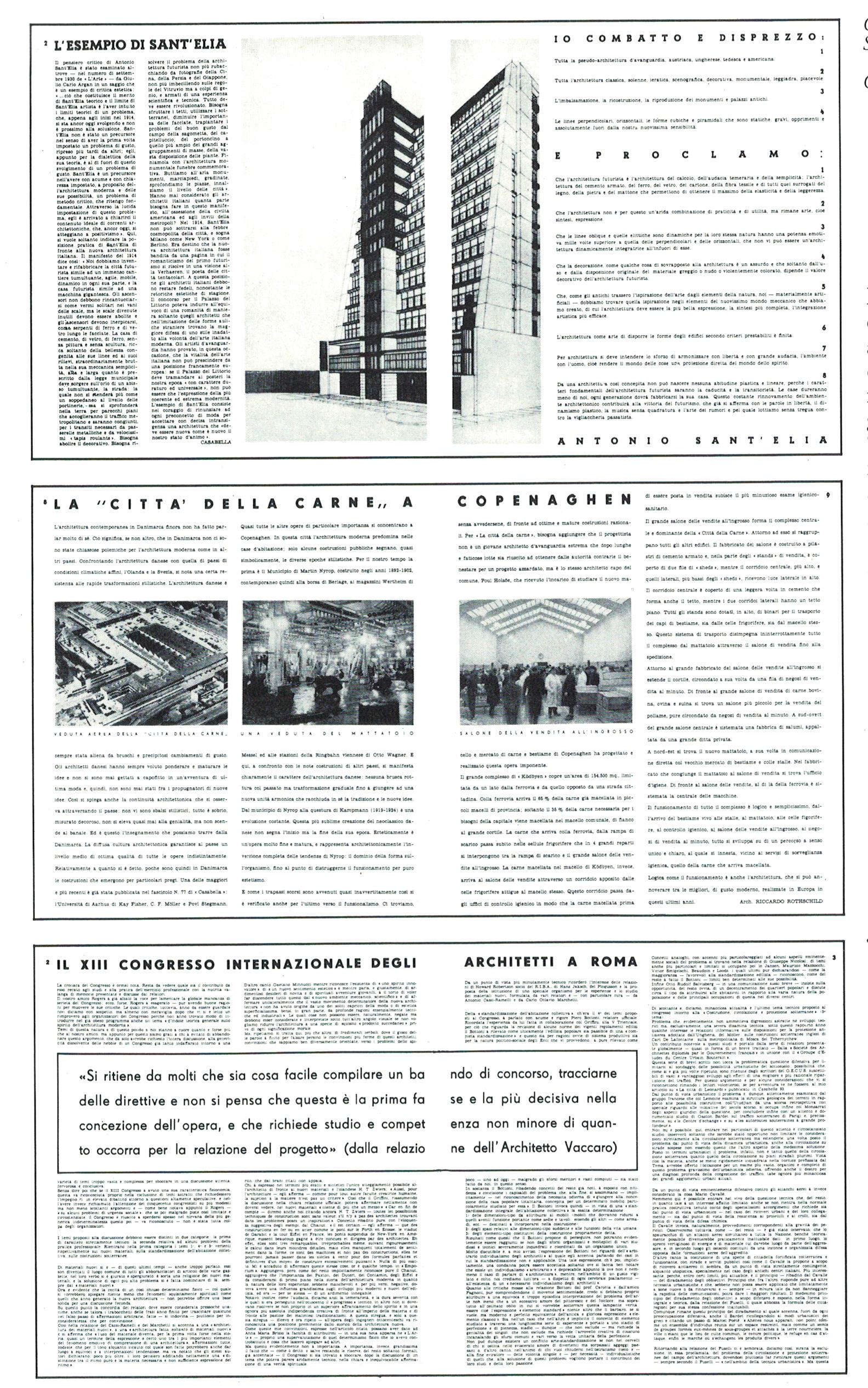

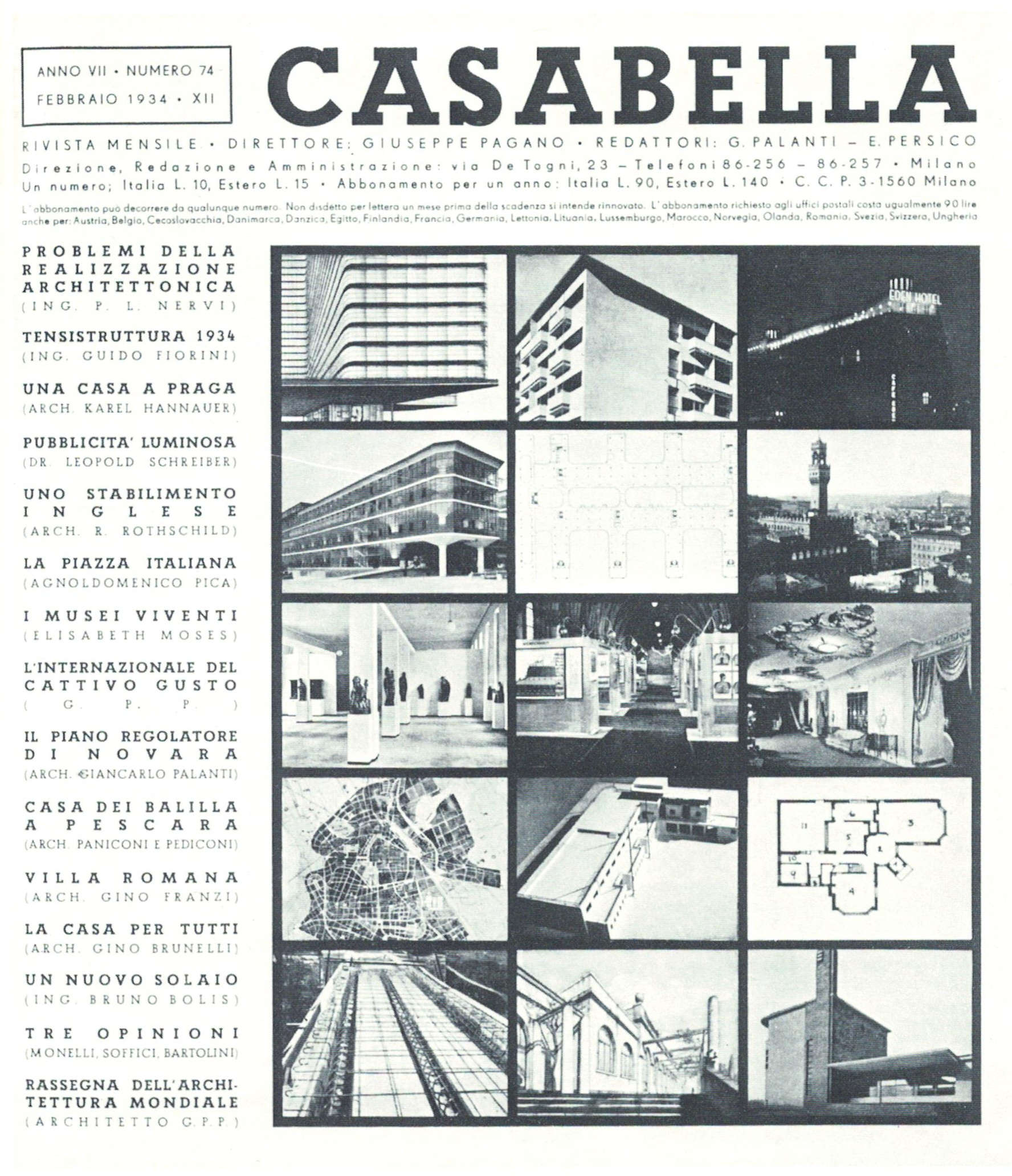

What can be said immediately about Edoardo Persico, almost ninety years after his death, is that his approach to the historical-critical problem in art and architecture has found no heirs or interpreters who have applied his method. Not even in those who have grasped its novelty and emphasized its persuasive force. No one, in essence, has continued on the path traced by Persico for a metalinguistic approach to the work of art. Perhaps his convinced religious spirit got in the way? Or being an outsider who starting from literature and philosophy provoked in many professional architects a reaction of rejection of his rigor and his very polemic toward rationalism? However, it cannot be denied that he was the most brilliant militant critic in Europe between the wars for modern architecture. His work directed through a myriad of essays where he set the pace for the Italian rationalists and understood before anyone else the developments of the new architecture: He extolled the genius of Wright and Mies van der Rohe early on, posed the moral question of architecture in the Europe of dictatorial regimes, wrote capital texts such as Point and a Head for Architecture and Prophecy of Architecture that in the difficult years of fascism outlined a supra-historical horizon, the task of the architect beyond his own art. As Bruno Zevi wrote, when he spoke of architecture, Persico was thinking of something else, seeing beyond.

If we consider today the historical condition in which Persico and the artistic milieu found themselves under Fascism, we cannot forget that the Ventennio was also the one where the philosophy of crisis expressed its highest meditations on the future of European man after the immense destruction of the Great War and while another conflict was preparing to explode. Almost half a century ago the historian of philosophy Giuseppe Goisis had included the Neapolitan critic among “the Italian nonconformists of the 1930s, ”1 readers of Jacques Maritain. The context was the one outlined by Croce in Storia d’Europa, where precisely the Neapolitan philosopher “sings the swan song of liberalism.” He was not alone in this drift: Huizinga with Crisis of Civilization, Husserl with The Crisis of the European Sciences, Ortega with The Rebellion of the Masses, and a succession of “Spengler’s grandchildren” participated in it between the 1920s and 1930s including Berl, Drieu La Rochelle, Guénon, Scheler, Eliot, Chesterton, Malaparte, Toynbee, Mounier, Berdjaev, Heidegger, and others could be recalled, who "echo the terrible stroke of the crisis.“ Into which the category of ”reactionary modernism" also falls, in its own way. Goisis-after recalling the most specific study on the debate of those years, J.L. Loubert Del Bayle’s essay on the broad audience of the Nonconformists of the1930s2 -rightly points out that “for all these writers the great crisis is the point of accounting for an entire civilization, an entire culture.” The “nonconformists” fought liberalism and capitalism as much as they fought communism; fascisms and democracy itself as it was credited overseas; virtually all forms of modern regimes were rejected as denying, as expressions of the great systems, human freedom and the citizen. Persico was certainly of these3, and Goisis notes that for all of them it was a matter of “necessary revolution,” in the ethical sense, that witnessed by Charles Péguy for whom “revolution will either be moral or it will not be.” Clearing the field of misunderstandings, the Italian scholar made it clear that to speak of Maritain’s influence on antifascism "one must beware above all of a mystical vision of antifascism. An antifascism born by parthenogenesis, absolutely opposed (because already constituted and compact) to fascism, understood in turn in the demonic manner of a radical evil and, moreover, lacking in its interior nuances and contradictions.“ Persico also quotes Péguy and Maritain repeatedly. And if the young people of the 1930s have a thirst for transcendence, they are ”religious spirits,“ this is also evident from certain ”confessions“ of Persico, who for himself speaks of ”obstinate Catholicism." But the coin has a flip side: the new anxiety for the religious also favors, for example, the Fascist School of Mysticism supported by Arnaldo Mussolini.

The great historical question is one that makes fascism and anti-fascism a dialectical pair, just as happened with Catholic and secular membership (all the more so after the Concordat). Persico, in these years, repeatedly professed himself to be a man of faith and in an often tormented way (as when in 1934 he confessed to himself, “I feel the end of Catholicism, Catholicism is finished! Yet it must live because God exists”). Fascism is not a matter that arises from ideology, it arises even before that on the mud of the Great War kneaded with the blood of so many young men who fell at the front, thus for a generational matter, on the immature consciousness of a people that Gobetti reads as the “autobiography of the nation.” This “inadequacy” that takes root as “voluntary servitude” brings back to the forefront the nineteenth-century question, that is, the lost opportunity of the Risorgimento uprisings; the “decisive childhood,” where - Raffaello Giolli wrote in turn in a merciless but honest book, published posthumously in 1961 by Einaudi, La disfatta dell’Ottocento4 - the old world after the revolutions of 1848 “had emerged from the nineteenth century stupendously organized, so as to be able to resist, in its foolishness, still more than one shake-up. Amid so many defeats, only this world of rags remained standing stubbornly, with the passive resistance of fairground puppets (...) Six or seven thrones had fallen here; but the ceremonial had been saved.” “Now in the kingdom of Italy, the Italians are still the same as before: however, the unruly and the whimsical have been excluded.” And Giolli thus concluded: having made Italy, “not the Italians were to be made, but the men. ”5

It was also a common thread in Persico’s polemic around the arts in Italy in relation to Europe, targeting architects and accusing them of a lack of style, a querelle directed, at one point, against the rationalists of Group 7 and the magazine “Quadrante,” with excesses of ’intransigence that spread to Terragni and Luciano Baldessari, after the latter had placed in front of his Padiglione della Stampa five cylinders-columns, evoking the new industrial propylaeums, like chimneys, with an abstract-rational appearance (if he had ever made it in time to see the Como-born architect’s design for the Danteum, what could Persico possibly have said about that forest of columns occupying a good part of the space?). Claudio Pavone-the leftist historian who in 1991 was accused of revisionism for publishing A Civil War . A Historical Essay on Morality in the Resistance- , was also the scholar who christened Giolli’s work thirty years earlier. In the introduction, Pavone placed Giolli right next to Persico: “In the Milanese group that constituted one of the liveliest nonconformist centers of those years, engaged in the struggle against the rhetoric of Romanity, he represented, with Edoardo Persico, the pole of the unconceded adherence to fascism, as opposed to theother, formed by Giuseppe Pagano and Giuseppe Terragni, of the trust, at first, and even at length, accorded to the innovative elements of which the regime proclaimed itself the champion”; and Pavone concluded by quoting an emphatic thought by Zevi on Persico: “He came to architecture in the desperate search for a civilization.”6

Despite the documentation available to us, ever since the first reconstructions of Edoardo Persico’s life and thought attempted after his death on the night of January 10-11, 1936, no one has yet been able to explain not only the shadowy areas that still accompany his biography, but also the fabric, or texture, of his thought, which is often considered too fragmentary or, so to speak, unsystematic. Historian Manfredo Tafuri was one of the rare interpreters who instead grasped the kernel of a methodology “in fieri,” calling Persico’s an “operative criticism”: “Since the circumstances of action are constantly changing, Persico does not care to safeguard the consistency of his judgments over time. ”7

On Persico’s biography and the secrets it is full of, much of what can be said is probably also limited by the removal forty years ago of part of the documents that were included in the folders of Giuseppe Pagano’s archive once deposited at the Feltrinelli Foundation in Milan. There was also a few decades back an appeal promoted by Giovanna and Lorenza Pogatschnig, Pagano’s daughters, and signed by dozens of intellectuals, to demand their return for the benefit of anyone who wanted to study them. The culprit was identified as the architectural historian Riccardo Mariani, who had had the Feltrinelli Foundation give him the folders concerning Pagano and Persico in order to carry out the research from which the Persico anthology published in 1977 would have resulted; however, in 1978 in an interview with Maurizio di Puolo he said that the entire dossier was still at Feltrinelli.8 Mystery. After Andrea Camilleri published Dentro il labirinto (2012) his reconstruction of the “Persico case,” in many parts fanciful and set to the literary “detective story” pattern, my very extensive review where I recalled the disappearance of the documents (Mariani had meanwhile died in Geneva, where he had lived and taught for years) was followed by a sibylline message from a person I did not know, the architect Paolo Baldeschi, who told me to be calm because the folders were deposited at the Gabinetto Vieusseux in Florence. In case this was true, it would have been a remarkable step forward, but my verifications led to nothing; on the contrary, Baldeschi’s claims were refuted by the reply I received from the director of the Institute, Gloria Manghetti.9 Full stop?

The moments of greatest concentration of studies dedicated to Persico date back to the postwar period and stretched to 1964, when Giulia Veronesi edited the two volumes bringing together Tutte le opere (1923-1935), published by Edizioni di Comunità10; the same Veronesi four years later also edited a volume of Persico’s Scritti di architettura (Florence 1968); then it was Mariani’s turn in 1977 to have the anthology Oltre l’architettura published by Feltrinelli. Selected Writings andLetters, 11 a volume that generated quite a bit of controversy because the editor questioned some official truths about Persico, particularly that of his anti-fascism. Mariani expressed his thoughts more explicitly the following year in the interview with Di Puolo already mentioned, where, among other things, he reiterated his conviction that Persico should be interpreted in the light of his religious spirit, “beyond architecture” precisely, and with a journalistic boutade went so far as to make the Neapolitan critic part of an excellent triangle: “the liberal Gobetti, the communist Gramsci and the Catholic Persico.”

The greatest disagreements came when Mariani confirmed his hypothesis that Persico’s death had matured in the circle of anti-fascism that gravitated around “Casabella,” where Persico now carried out leading work but at the same time had to contend with opposition that was as much external, among architects who did not appreciate his rigor when he then agreed to execute works born at the behest of the regime; as much as internal, from those, Pagano himself, who then had to mend the pieces with respect to Persico’s criticism of the representatives of regime architecture (to his wife Sira, on November 14, 1933, as evidence of a heavy climate in place toward him, the critic confessed: “Know, however, that my place at ’Casabella’ is very much threatened: I will not stay long because the magazine is not going...”).

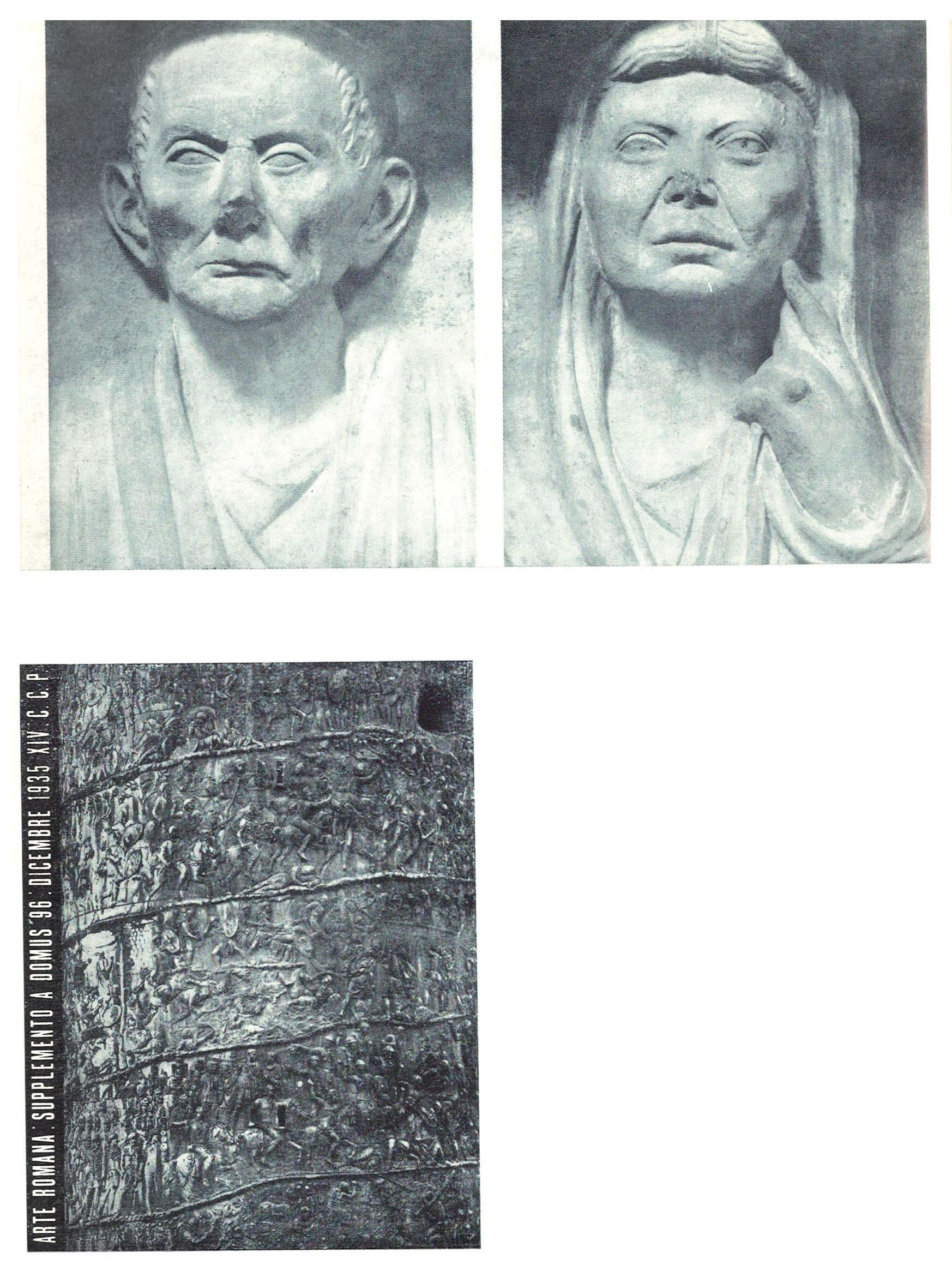

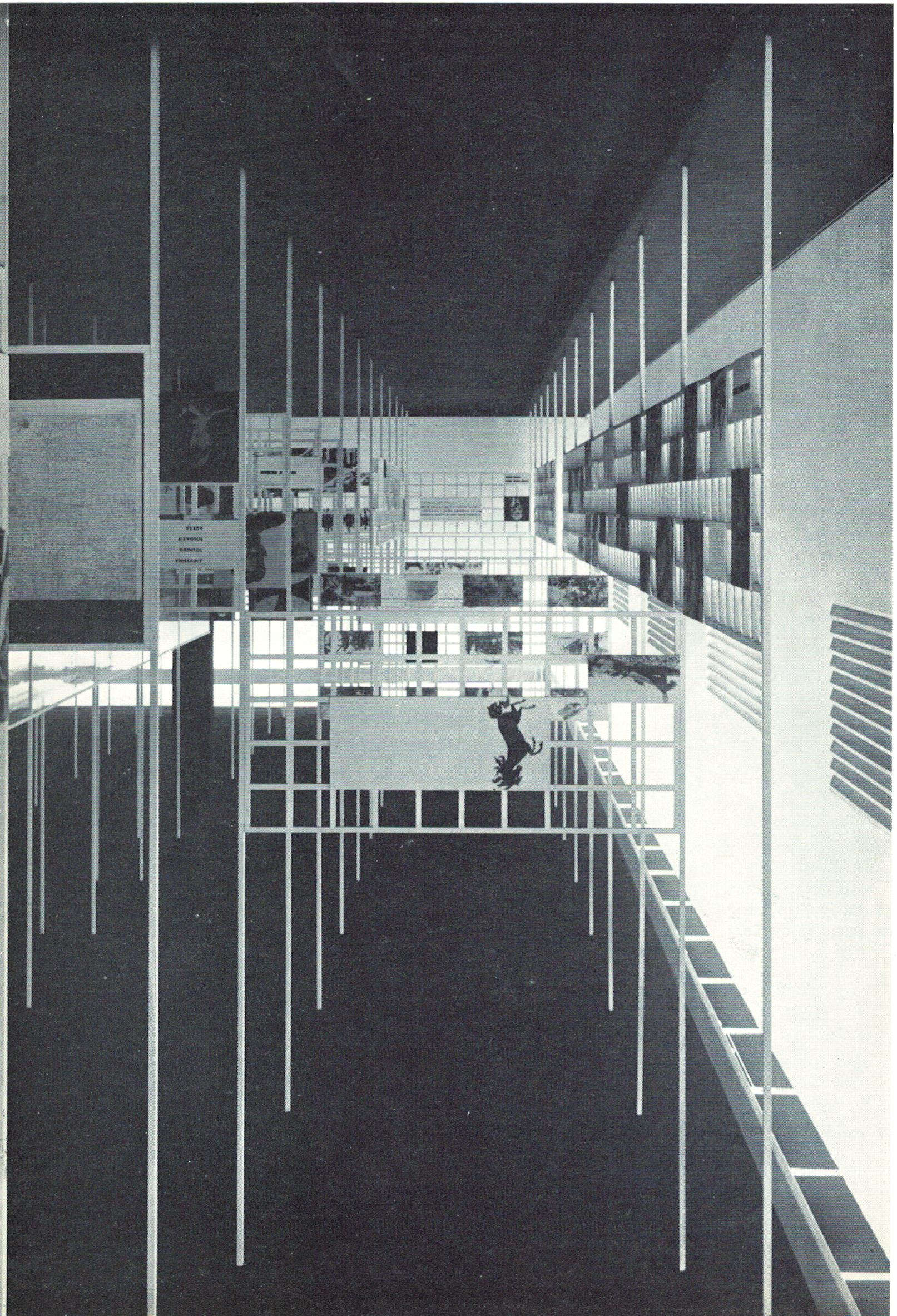

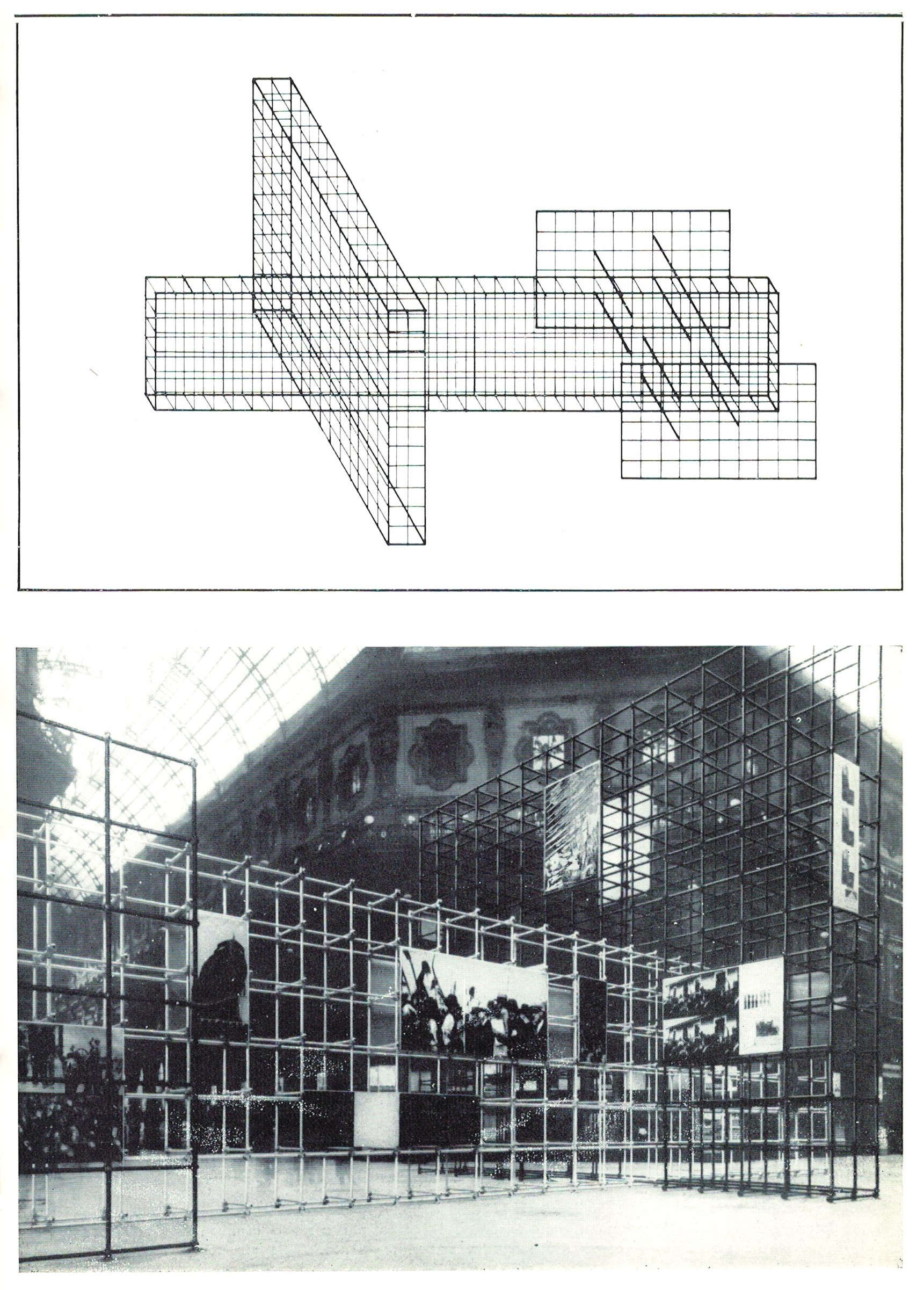

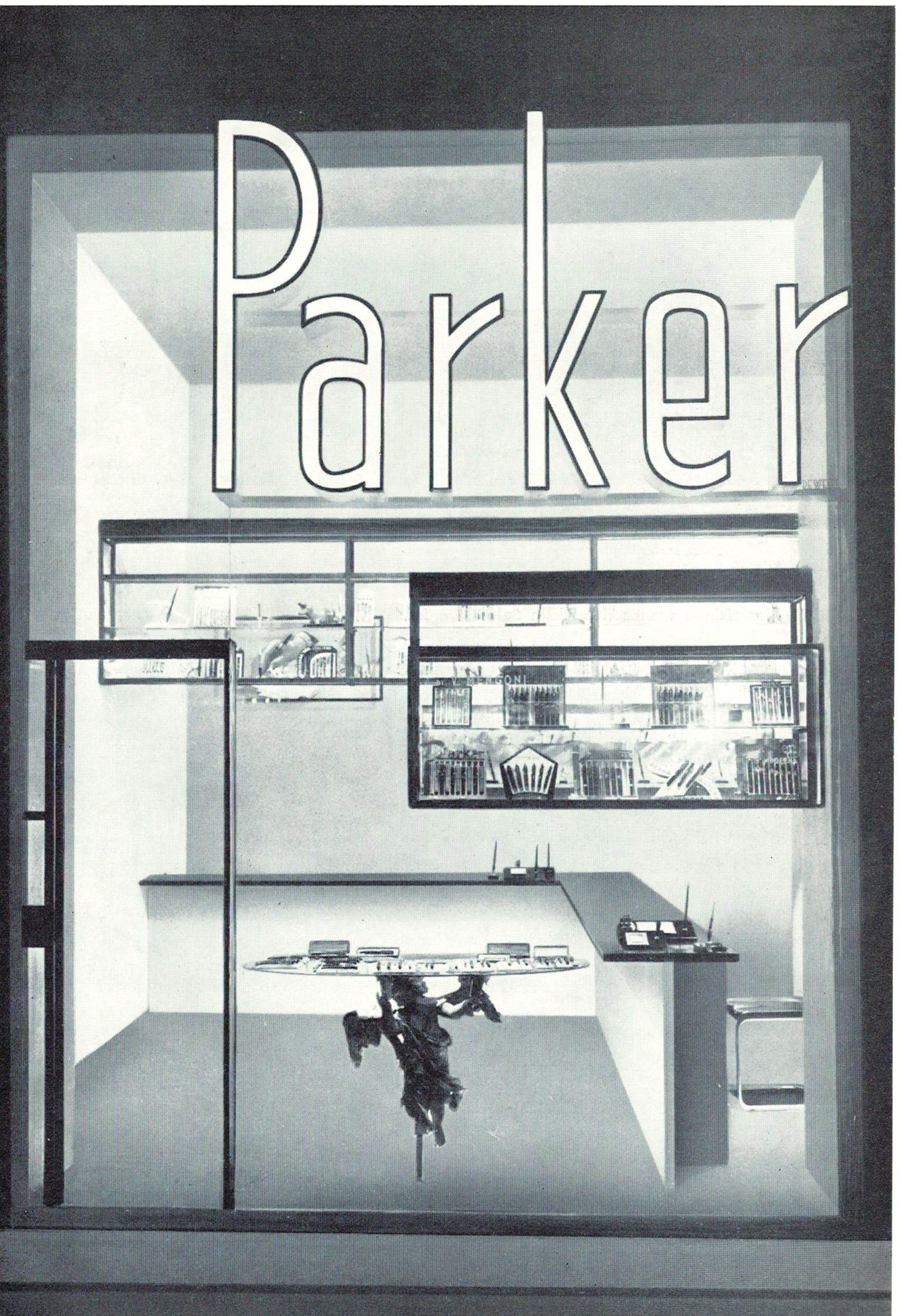

As Persico’s parable comes to its end, editing the “Domus” supplement Arte Romana in December 1935, that is, just a few weeks before his death, Persico is very restless and confesses to Giulia Veronesi the doubt that he has taken a wrong shot, indeed he fears for his image and his own moral figure: “This work will remain as a stain in my life. I should not have dealt with it. ”12 In fact, it is an editorial masterpiece and a most elegant example of critical and visual counterculture; yet, Persico macerated. Why? The theme, wrote Veronesi, “had been chosen in the ’Roman’ spirit of the times, by the publishing house, Domus,” and Persico “made it a subtle work of opposition to current rhetoric.” This was confirmed, as early as 1936, by the words of art historian Anna Maria Brizio: “Another battle fought in favor of the need to bring back to unitary criteria the judgment of art, against the insufficiency of current archaeological methods. It is also an affirmation of modernity (...) sharpening the weapons to defend forms particularly dear to our sensibility.”13 The truth is that that volume came after the extraordinary “ephemeral” architectures of the Hall of the Gold Medals at the Exhibition of theItalian Aeronautics (1934) and the metal advertising construction for the Plebiscito in the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele in Milan (1934), where Persico, working with Nizzoli, had reached absolute heights of modernity and poetry, however “celebrating” precisely the institutions of the Regime, and this had aroused ill feelings in some anti-fascists. Persico, perhaps, was considered a double agent by these opponents. Everything in his words, however, seems to testify to the contrary. After these works, even the Salone d’Onore at the VI Triennale in 1936, the rationalist apotheosis edition, would have sufficed to dispel any suspicions that might have arisen (but he died before seeing it realized). Gino Severini, commemorating Persico’s passing, had put him on the side of those who choose uncomfortable positions, "exposed to all winds, to all assaults from opposing currents. "14 It is hard to deny that Persico’s own attitude might have raised some doubts, in an ambiguous conduct that moreover dragged on from his youth in Naples: Persico man of mysteries? His own death, as ironically, was called in the police report, “mysterious.”

It is safe to assume, then, that a volume such as the one on Roman sculpture might have overflowed the vessel of patience in those who did not tolerate that sophisticated mode of criticism, seeing in it, on the contrary, a real betrayal of anti-fascism. Suffice it to recall, in this regard, the intransigent position of Attilio Rossi, who refused to publish in the magazine “Campo Grafico” the posters for the Plebiscite studied by Persico and Nizzoli, and in 1983, in the book celebrating the magazine’s anniversary (1933-1939), he gave the reason thus: “There was opposition to the fact that modern graphics, a most effective means of communication, served to spread lies.”15 It was certainly a coherent choice at the time, but Veronesi writing the essay Political Difficulties of Architecture in Italy (1920-1940) broke a lance for Persico by observing that he “believed as few do in the influence that ambient taste exerts on customs; he believed in the persuasive, as well as symbolic, force of ’form’ implying moral content.”16 It was on this that Persico had based his maieutics: style was the man himself, not a formal ideology.

However, the news that emerges after more than half a century of study on the “Persico case” is minimal compared to what was known-or could have been known-immediately after his death: Mariani, with a somewhat nonchalant approach, stated in 1978 in his interview with Di Puolo that a climate of omertà prevailed, hinting that having taken an interest in Persico’s death had also brought him some difficulties as a scholar; and speaking of a “giallo” he compared it to a new “Majorana Case.” Let us ask, however, why should Persico be so troublesome even today? According to Mariani, what brought down the curtain of silence among those who knew him, beyond the condolence messages, were the unclarified circumstances of the critic’s death: perhaps there were responsibilities that still, almost a century after that story, can cast shadows on someone’s good name? That Persico had a negative view of the weaknesses of anti-fascism is no secret. For Mariani, the issue was about “the order that he contrasted with disorder, and the disorder also of the antifascists who were doing antifascism without recalling a specific order. Gramsci called back to an order that he presupposes, that he invents, that he devises. The others did not call back to anything, they were anti something, but they had not had the time or the intellectual capacity to create an alternative system to fascism.” It was the same accusation that Persico as an architecture critic made most frequently against the Italian “rationalists,” the failure to be capable, Gobettianly, of “believing in precise ideologies,” that is, “the thorny problem of Italian life.” An issue Giolli also spoke of, who had close dialectical relations with Persico but also very close in polemical context. In the immediate postwar period it was one of the most recurrent themes with the sudden changes of barricades of those once fascist, and for this reason called “turncoats”; for so many reasons, it continues to be a past that does not go away even today.

1. Aa.Vv., Jacques Maritain and contemporary society, edited by R. Papini, Milan 1978 (= Proceedings of the conference organized by the International Institute J. Maritaim and the Giorgio Cini Foundation, Venice October 18-20, 1976, G. Goisis, Maritain and the Italian “non conformists” of the 1930s, pp. 181-203)

2. J.L. Loubert Del Bayle, The nonconformists of the 1930s, Rome 1972.

3. Although his status as a Neapolitan dandy should be noted, that is-as Francesco Tentori wrote in what is to be considered one of the most disenchanted and at the same time capable of enhancing the genius of the critic, Edoardo Persico. Grafico e architetto (Clean, Naples 2006), where he notes his “upper-middle-class aristocratic snobbery,” p. 7, there is no hiding the fact that in addition to his enormous merits, Persico was also “a formidable, incredible, imaginative ball-teller on permanent duty (assisted very effectively , after his death, also by his wife Cesira/Sira Oreste),” p.17. The most discussed topic remains that of the phantom trips to various capitals, as far as Moscow, of which there are still scanty and improbable records to this day.

4. R. Giolli, La disfatta dell’Ottocento, Turin 1961 (edited by R. Giolli); introduction C. Pavone.

5. Ibid, pp. 322-323; 326.

6. C. Pavone, in R. Giolli, op. cit, introduction, p. XIV.

7. M. Tafuri, Theories and history of architecture, Bari-Rome 1968, no. 26, p. 184.

8. Edoardo Persico 1900-1936: autographs, writings and drawings from 1926 to 1936, exhibition catalog (Rome, Galleria A.A.M., Architettura Arte Moderna, January 1978, edited by M. di Puolo, Arti grafiche Privitera, p. 79.

9. A. Camilleri, Dentro il labirinto, Skira, Milan 2012. To my requests for clarification, Ms. Gloria Manghetti wrote to me, “Dear Doctor, Riccardo Mariani made contact with the Institute several years ago to see if there were conditions for a bequest for consideration of his entire archive. However, the necessary agreement was not found with the then top management of the Institute, and so the Mariani papers, which also included the Persico folders, were not received.” The same director reminded me, below, that "in 1980 a meeting and exhibition [Palazzo Strozzi, March 22-April 12] entitled Persico-Pagano: utopia and the practice of architecture in the 1930s were organized by the GV." The brochure that accompanied the exhibition, 8 pages printed by Arti Grafiche C. Mori, edited by R. Mariani, had an index as follows: "Persico: beyond architecture; From the diary of Giuseppe Pagano; Notes for a postwar building program."

10. E. Persico, Tutte le opere (1923-1935), edited by G. Veronesi, 2 vols., Edizioni di Comunità, Milan 1964.

11. E. Persico, Beyond Architecture. Selected writings and letters, edited by R. Mariani, Feltrinelli, Milan 1977.

12. G. Veronesi, Political difficulties of architecture in Italy (1920-1940), Politecnica Tamburini, Milan 1953, p. 108.

13. Aa.Vv., Edoardo Persico. Testimonianze e memorie, ed. Achille Lucini, Milan 1936.

14.G. Severini, Persico’s Humanism, in “L’Orto,” Year V, no. 6, Bologna, November-December 1935 - XIV. The journal probably came out in January 1936, in time to give the news of Persico’s death; with respect to the date of edition, in fact, it would be an inconsistency.

15. Cf. Edited by P. Rossi, Attilio Rossi, Edoardo Persico. A little publishing mystery from 1936, s.n., s.l. 1999. On the other hand, typographer Guido Modiano, who assisted Persico in the creation of the new graphics for “Casabella” and for other editorial initiatives, had to write about the volume Arte Romana that for “us in the trade [it was the] aesthetic testament of the greatest ingenuity that has worked, for years, in typography” (F. Tentori, op.cit., p.74).

16. G. Veronesi, Political Difficulties of Architecture in Italy, cit. p. 112.

The author of this article: Maurizio Cecchetti

Maurizio Cecchetti è nato a Cesena il 13 ottobre 1960. Critico d'arte, scrittore ed editore. Per molti anni è stato critico d'arte del quotidiano "Avvenire". Ora collabora con "Tuttolibri" della "Stampa". Tra i suoi libri si ricordano: Edgar Degas. La vita e l'opera (1998), Le valigie di Ingres (2003), I cerchi delle betulle (2007). Tra i suoi libri recenti: Pedinamenti. Esercizi di critica d'arte (2018), Fuori servizio. Note per la manutenzione di Marcel Duchamp (2019) e Gli anni di Fancello. Una meteora nell'arte italiana tra le due guerre (2023).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.