Drawn and Dreamed. The Thousand Women of Lutz Ehrenberger

The author of this contribution, Valeria Tassinari, is curator of the MAGI ’900 Museum in Pieve di Cento, which houses one of the largest collections of Lutz Ehrenberger’s works, as well as curator of the exhibition "Homage to the Femininity of the Belle Époque, from Toulouse-Lautrec to Ehrenberger."

They have a special scent, a sinuous and sweetly penetrating line like a flowery effluvium, a smiling seduction: the thousand and perhaps more paper women who populated the art and life of Lutz Ehrenberger, offer themselves to the gaze, slight and winking like the dream of a timeless Belle Époque, in a roundabout of images to make your head spin.

What made the Austrian artist a multifaceted interpreter of feminine seduction was, in fact, precisely his peculiar ability to continue to spread a fragrance of carefree beauty, preserving, even after the outbreak of the Great War, that positive lightness that soon dissipated completely elsewhere. As if the glittering energy of the Belle Époque, the golden frame that formed him and gave him his first notoriety, had always continued to protect his life, his dreams and his imagination, even when the world around him stepped out of the picture and plunged into a whole other reality.

A talented painter but above all a graphic artist and illustrator, Ludwig Lutz Ehrenberger appears to us today, in the midst of study and due rediscovery, one of the most fascinating and prolific authors active between Paris and Mitteleuropa in the first half of the twentieth century. Brilliant, attractive, jolly, established and original in his work, fashionable but never trivial, inventive and amused: this is how the stories handed down orally by his heirs, the eloquent period photographs and, above all, his vast creative output restore him. A production intended mainly for publishing that, today, while we are still moving along a not easy path of philological reconstruction of his biography and career, already clearly shows us the importance and unmistakable fragrance of an imaginative and sensual inspiration.

In the absence of monographic publications (the only monographic publication on Lutz Ehrenberger that we currently have is the small catalog of an exhibition held in Castelfranco Emilia, at Palazzo Piella, in 2002, with a critical text by Bruno Vidoni, curator of the exhibition. Due to a transcription error in the title and in the texts the artist is named Ehremberger) and of a timely biography, therefore, we can try to relive his story mainly through the works, many of which are still spread in a fragmentary way on the antiquarian market. And it is precisely by looking at them that it becomes easy to think that if we really knew a few more episodes of his life, or if we still could directly gather the testimonies of those who knew him, certainly happy words would chase each other, speaking of the charming Lutz, disenchanted interpreter and, perhaps, last heir to theinebriating frivolity of the Belle Époque.

|

| Lutz Ehrenberger in his studio |

In the heart of Mitteleuropa

After all, when Ehrenberger was born in Graz, March 14, 1878, the era of enthusiasm was blossoming. In the Austrian city, albeit in the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s climate of austerity, life is quite good; in general, these are years of modernization and economic recovery, and his is a family of solid prosperity that can afford to live fully in the moment. His father is a landowner; his grandmother, Baroness Bekönyi, attends Vienna and encourages her grandson’s enrollment at the Priesten-Kloster High School, where the young man completes his humanistic studies, and then at the capital’s Academy of Fine Arts. Late nineteenth-century Vienna is a city that seems to be growing up everywhere, a nerve center of Mitteleuropa experiencing major social and cultural transformations that are strongly incisive internationally. Its face changes, both in terms of urban planning, thanks to the Ring, which has just modernized its spatial configuration, making it a model avant-garde for urban development, and in terms of architectural experiments favored by the bourgeoisie’s love for the Jugendstil. In the ages in which the concept of modernity reigns, academic circles and the more experimental fronts separate, clash dialectically, and not only in the classrooms of state academies, but especially in the workshops of schools of applied arts, theaters, salons and cafes, where the enlightened bourgeoisie becomes passionate about aesthetic and art issues. If the Academy remains the place of education par excellence, it is only because in it and against it, heated and stimulating confrontations are unleashed. In Rome on the Danube, the best minds of Europe synchronize over dinner and strolls, attracted by a ferment that resonates in music, words, drawings, magazines, and the comfortable or exotic elegance of fashionable clothes.

Lutz, then, studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, under Siegmund LAllemand (1840-1910), a fine academic painter of realist impressions who had made a career as a war artist, and who was an advocate of the virtuosic tradition of the brush (his name appears on the commission that refused Adolf Hitler’s admission to art studies in 1907). But, among the professors of the Akademie der bildenden Künste was also the more open-minded Alois Delug (1859-1930), a prominent portrait painter of Bolzano origin, who between 1896 and 1898 had been at the side of Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, Koloman Moser, Joseph Hoffmann, Otto Wagner and numerous other founders of the Vienna Secession.

The spirit of the new cannot have failed to reach him, not least because soon afterwards Ehrenberger would complete his studies at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, another vibrant center of Secessionist experimentation. Here the discussions, the exhibitions, the very style of presentation of projects, on the borderline with the applied arts, certainly attracted his attention, so much so that he often used a square symbol (a kind of monogram) in his graphic plates, plausibly derived from that particular geometric aesthetic that would soon characterize the style of the Deutscher Werkbund. But the geometric lastration toward which the new research leaned never actually seem to have convinced him completely, or even vaguely tempted him, and nothing seems to have prompted him to abandon his figurative and elegantly realist language. After all, in order to experiment with the avant-garde path of abstraction that was being radicalized in those circles, which were interested in the reduction of ornamentation and the construction of a rigorous relationship between form and function, Ehrenberger would have had to sacrifice his own penchant for soft silhouettes, minute decoration, and the narrative of the good life, and perhaps forgo editorial commissions, which soon came instead.

In 1904, at the age of twenty-six, he took a studio in Saalfelden am Steinernen Meer, a charming town in Salzburg, where in 1906 he would have an elegant Art Nouveau villa built, which he affectionately called the Little House of the Good Morning, and which he would always consider his corner of peace. But intellectual solicitations were to be found elsewhere, so in 1908 he took up a second residence in Berlin, where he opened a studio on Güntzelstrasse in the heart of the city. Here he was able to frequent the circles of the Academy of Fine Arts and, it seems, the Weimar School of Applied Arts, where he probably came into contact with Walter Gropius.

The Great War, devastating for many young people of his generation, apparently for him merely a theme that sinsinuates among the subjects of his drawings for illustrated magazines, does not seem to have left too deep a mark on his life. During the most dramatic years his artistic activity apparently continued uninterrupted, as evidenced by his participation in 1918 in a major exhibition of German art in Baden Baden along with a large number of talented artists.

After an early divorce from his first wife, in 1914 he married the beautiful Lydia Horn, whom he had met in Munich during his student years. The girl’s siblings, Ugo and Elvira, are well-known photographers in Trieste, and she, who evidently comes from a sensitive alarte background, is an elegant and cultured woman, and will be his ideal and devoted companion for the rest of his life. They spend their vacations together in the villa, with the bright studio where models pose, a large kitchen where Lutz delights in cultivating his taste as a great gourmet, the exclusive swimming pool and the relaxing view. Saalfelden will be a landmark, the setting for their love, until the end. Although the quiet life in the mountains certainly does not displease Ehrenberger, the big cities do not cease to be an attraction, for all they offer professionally, culturally and, why not, also for entertainment, given his reputation as a gaiety viveur, well documented by photos that show him as the protagonist of lighthearted parties, almost two meters tall and decidedly corpulent: a smiling big man and great eater, who gladly poses, joking with friends.

But besides Vienna, Munich and Berlin, where in the second decade of the century he already had numerous contacts, what other city could have attracted him if not Paris? Since the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the ville lumière has been everyone’s dream; it is the place where anything happens and anything can happen, thanks to its beauty, the liveliness of cosmopolitan salons, great exhibitions and countless nightclubs, which offer all kinds of shows and entertainment. Thousands of creative people move there to express their talents, many working in graphic design and illustration and going on to seek success in the great agencies that pioneered modern advertising, arriving from all over Europe and America, open and ready to join together in rowdy and cosmopolitan communities. They all meet and get to know each other, moving between the areas of Montmartre, Montparnasse, and of course in the transgressive night of Pigalle, where the blades of the Moulin Rouge glittered and the new clubs opened in which the city’s most licentious dancers performed, the kind of women whom the works of Toulouse-Lautrec had already redeemed from the slums and brought into myth.

Impossible, at that moment, not to long for Paris, not to consider the French capital the unmissable place to seek out the great bargains, to see the best of fashionable artists and works, to experiment and experiment. Lutz presumably moved there in 1919, just after the war. By the 1920s they were all there, or had already been there: from Boldini to Helleu, from Corcos to Cappiello, from Sepo to Picasso (just to name a few, among the many who really became well known), all swept up and thrilled by a youth that seemed eternal, ready to dive into the joyous moveable feast extolled by Ernest Hemingway, that “Paris of the good old days, when we were very poor and very happy.”

|

| Lutz Ehrenberger, Carnival in Paris (1922) |

|

| Lutz Ehrenberger, Dancer with Figure in Red (1929) |

Unmissable Paris

By the 1920s, however, Ehrenberger, who was never poor and certainly was not poor at the time, was an artist with a mature language who had come to Paris to solidify his notoriety and recognizability, which usually makes one happy. Nearly the same age as Picasso, twenty years older than the lost generation (as patron Gertrude Stein called it) of Hemingway and his transgressive friends, he does not seem to take an interest in the more experimental davanguardia movements (Cubism, Futurism, Abstractionism, Dadaism are all well on the art scene, and soon Surrealism will arrive), while he is very familiar with parties and nightlife. In the city he took up a studio in a beautiful central area, Rue de La Fontaine, in the 16th arrondissement, a neighborhood of fine Art Nouveau buildings stretched between the Seine and the splendid Bois de Boulogne, the park of the most elegant promenades and the most intriguing encounters, which of course he would not fail to immortalize.

In a painting depicting the view from his studio, painted quickly and with a synthetic tension rarely found in other subjects, Lutz seems to want to remember forever the opening onto the ashen blue, the serene atmosphere and the dueling panorama over the snow-covered rooftops, offered by a view from above, probably taken from the hatch (the railing is clearly visible) of one of those romantic little apartments, which were carved out of the rooftops of stately mansions to rent to artists and intellectuals.

Paris offers itself here in a silent vision, dominated by the familiar silhouette of the Sacre-Coeur, perched on the hill of Montmartre, looming in the background; elsewhere, in nighttime walks, the city reveals itself in stunning modernity, beneath the soaring spire of the Eiffel Tower that has now become its universal symbol. Almost everywhere is plastered with advertising posters, visual messages of strong appeal drawn by the brightest pencils of the moment: thus the walls and streets of greatest passage are like great exhibitions, collective and popular, animated by powerful images that reach all social classes indiscriminately, in the bustle that animates the center at every hour. The colors, slogans, and lettering convey more than just promotional messages; the temptation to consume is expressed in a constant seduction of glances, winks, gluttony, synesthesia, models to imitate, style icons. In their overlapping in a dynamic palimpsest, continually invading and modifying the urban horizon, the formidable affiches, disseminated thanks to the close understanding between art and industry, synthesize in the imaginary, offer life lessons, delight and orient desires, educate to vision, interweaving all expressive registers, from the more illustrative ones still in the Art Nouveau taste, to the more experimental ones, inspired by Cubism, Abstractionism, Futurism. As a painter, Ehrenberger continues to seem not at all interested in those davanguardia researches. We do not know exactly his pictorial production in those years, but he could reasonably have devoted himself to fashionable portraits, which rendered well and favored the inclusion of artists in the refined circles of the bourgeoisie; an activity, that of portrait painting, which we know he conducted successfully even after his new move to Munich in 1935. From his portraits, among which there is also a beautiful self-portrait, we understand that the pictorial language will always remain faithful to a rapid realism, although, in the later 1930s he will show a greater aptitude for the cleanliness of forms, in line with the aesthetics of classical and Aryan taste disseminated by the cultural policy of National Socialism. In any case, among the exhibitions he participated in during the Parisian years are official events such as the Salon dAutomne, and we can well believe that his name circulated in the right salons.

As an illustrator, and of this instead we have certainty, between the second and fourth decades of the twentieth century Lutz published many illustrated plates, largely under the pseudonym of Henry Sebastian, a French darte name adopted perhaps to maintain some anonymity with respect to certain increasingly erotic images (which he placed on the market in folders, notebooks, and thematic collections), or perhaps simply to keep his advertising production distinct from that of illustrator and editorial graphic designer. In both spheres he works extensively, at high levels. Perfectly placed in the world of illustrated magazines, especially satirical and lifestyle magazines, which are depopulated and now achieve great popularity even among a female audience, Ehrenberger establishes very lasting collaborations with some of the most internationally renowned titles, and moved synchronously between Austria, Germany, and France, publishing in magazines coveted by the best illustrators of the time, such as Uhu, Simplicissimus, Kurt Ehrlich Verlag, Das Magazin, Elegante Welt, Lustige Blätter, La vie Parisienne, and Le Sourire.

His style changes little over time, seeming more inclined to adapt to changes in fashion, readily recorded in clothes and beauty patterns, than to experiment with variations in language. He retains hints of Jugendstil in the sinuous lines, in certain golden exoticisms and subtle eroticism, but he is not fond of the graphic synthesis of Japanese prints, which had aroused so much admiration in Toulouse-Lautrec; his irony is sly, he does not scratch with the snappy marks typical of certain German expressionist draughtsmen, or with the grotesque irony of caricatures, as did, for example, Lyonel Feininger, his colleague for Lustige Blätter.

Basically, he is an aesthete: little interested in political satire, despite some caricature play he matures a predilection for costume illustration, elegant and subtly mocking, in which one can read in the watermark an amused attitude towards a frivolous society, which corresponds to the target of his readers, whose growing number is now to the well-balanced between both sexes. And both sexes Lutz seems to address with identical attention, even if on the surface some of the images might appear to be reserved for gentlemen. An illustration for the January 29, 1919, fashion magazine Elegante Welt, Der Tanztee, for example, shows us a scene of elegant entertainment in which a slender, Ã la page couple moves in perfect synchrony, suggesting that she and he have the same desire to be looked at and admired by the public. If in the 1920s it will certainly not be the authoritarian male who will fascinate readers and readers, then here is an early emergence in his sensibility of a worldly and sought-after idea of masculinity, not devoid of petty frivolities, which will be revealed in the male companions, always intent on admiring the ladies and even imitating their attitudes a little.

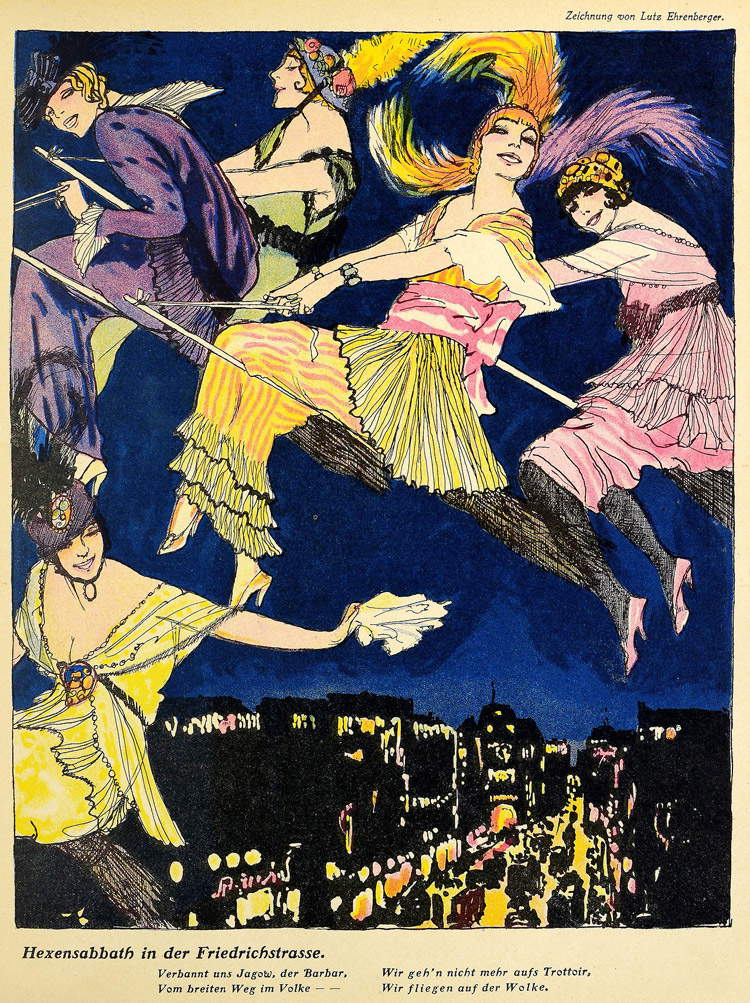

Among the German-language magazines, the one with which Ehrenberger maintains one of the most enduring collaborations is Lustige Blätter, for which he produced many covers and interior plates, as well as designing the covers of the novels that the same publisher published periodically as a supplement to the magazine, and could boast a high circulation, as well as wide distribution. Lustige Blätter (the funny pages) was a Berlin satirical magazine founded in 1886 that, as its subtitle declared, intended to bring together the best German cartoons, and was published by publisher Otto Eysler until 1944. Through its issues, which were also reproduced and circulated in France, it is possible to reconstruct the evolution of society from the beginning of the Belle Époque to the years of the Great War, often recounted with fierce irony, and up to the fall of Nazism, a regime to which the paper had aligned itself (for love or by force) as can be seen from the absence of political satire cartoons and the insistence on criticism of Jews during the Reich years. Lutz, who continued not to engage in satire, produced a series of large-format color tempera paintings for the beautiful magazine, always dominated by female subjects, declined over time in many variations, from the cheerful rosy-cheeked Tyrolean girl to the vermilion-lipped femme fatale, from the composed bourgeois lady to the unrestrained exotic dancer.

A striking colorist as well as a draughtsman with a quick and clean stroke, he also sometimes liked to experiment with a more modern type of illustration, reduced to the black mark of India ink (and how can one not think of an influence of Aubrey Beardsley’s Salome), but a twisted and tortuous mark, with which he amused himself by creating virtuosic interlockings of figures, dense seductive and allusive appearances, as seen in a curious series of works produced for Le Sourire around the mid-1930s.

For Le Sourire, a humorous weekly magazine for which France’s best pencils worked and, among them, Paul Gauguin and Leonetto Cappiello, Lutz often produced the interior plates, which were usually in black and white, and the front and back covers, which instead gave ample space to color. In the 1930s, the magazine had a predilection for sexy covers, dominated by somewhat exhibitionist divas, with provocative small breasts on full display and garters perched on very long legs, certainly very attractive to buyers. Ehrenberger is perfectly attuned to the objective. In a memorable 1933 cover, for example, the gesture of crossing the lady’s very long legs becomes the center of gravity of the composition, an almost hypnotic thigh break, enhanced by a long black train, around which the other elements the man waiting for her by preening her smugly, the hairdresser bustling around her curls, the waitress lacquering her nails, and even the defiant expression of the protagonist are only the frame.

In addition to publishing, as was customary at the time the artist probably worked as a poster artist for the cinema and as an advertising designer for major brands, such as perfumers Mouson and Coty, Marquard pianos, and Shell gasoline. Very long and very significant is the series of posters and small advertising inserts for 4711 Cologne Water, for which Lutz represents both the male and female lines, producing a profusion of images of idealized women and men, but sometimes so sensual that they attracted the attention of censors. In the beautiful line illustrations (which were published in black and white in the one-third or one-quarter page format) and in the color posters, a very wide variety of types appear, and the same, immortal fragrance is from time to time associated with the idea of adventure, romance, and seduction.

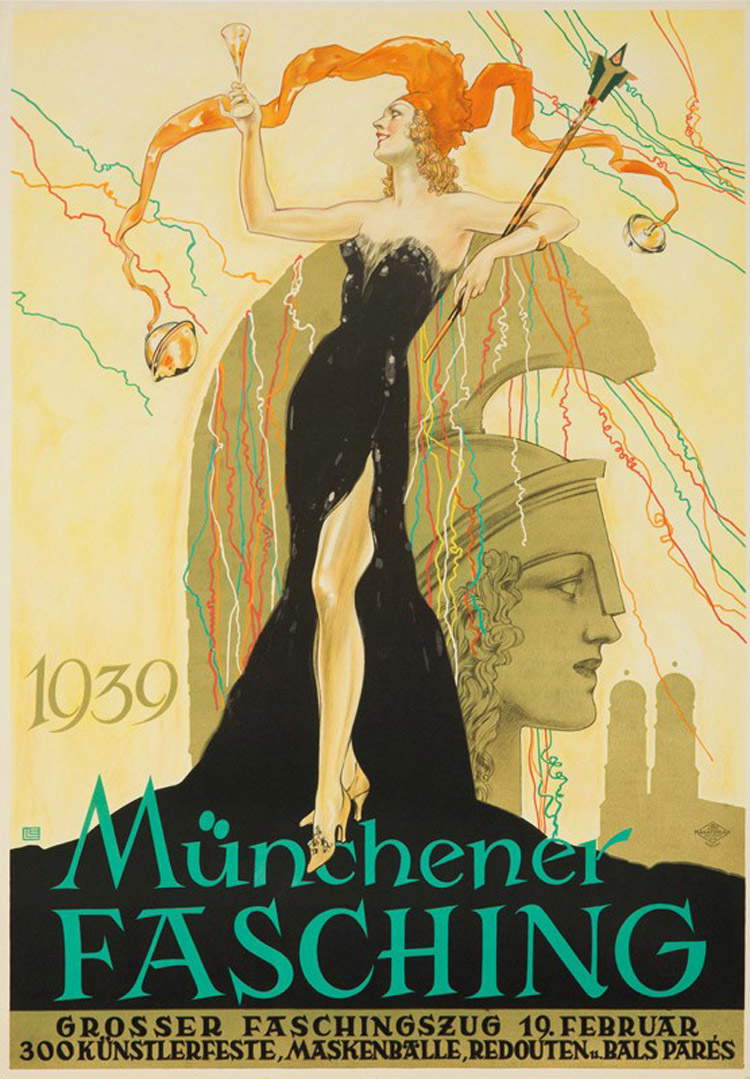

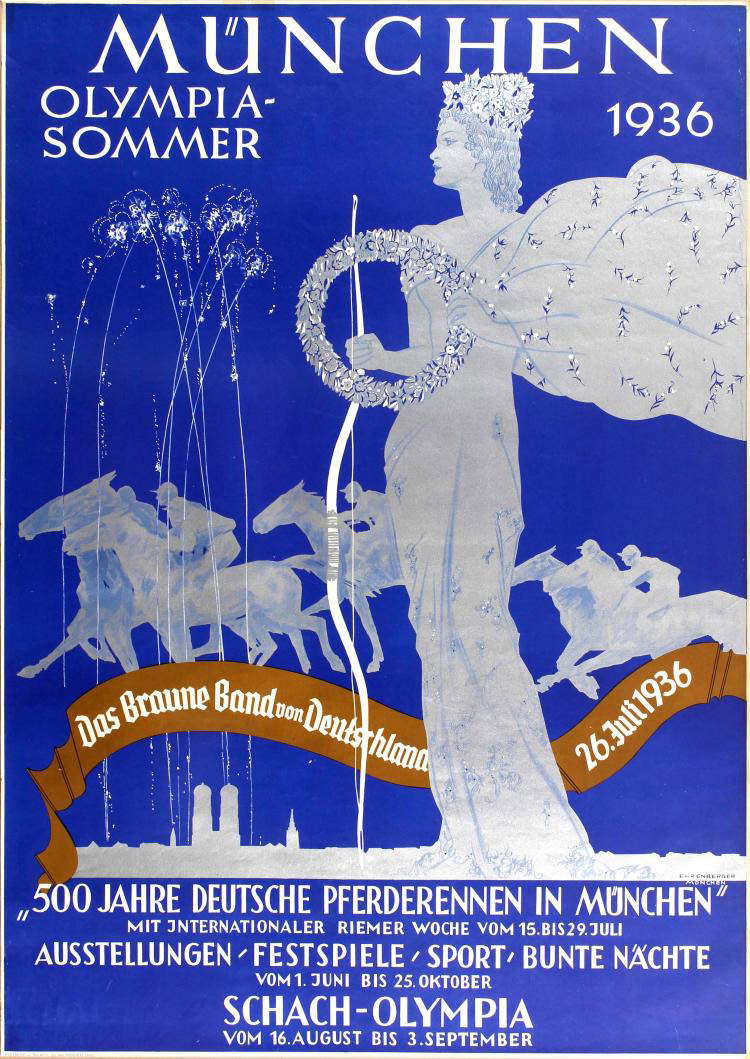

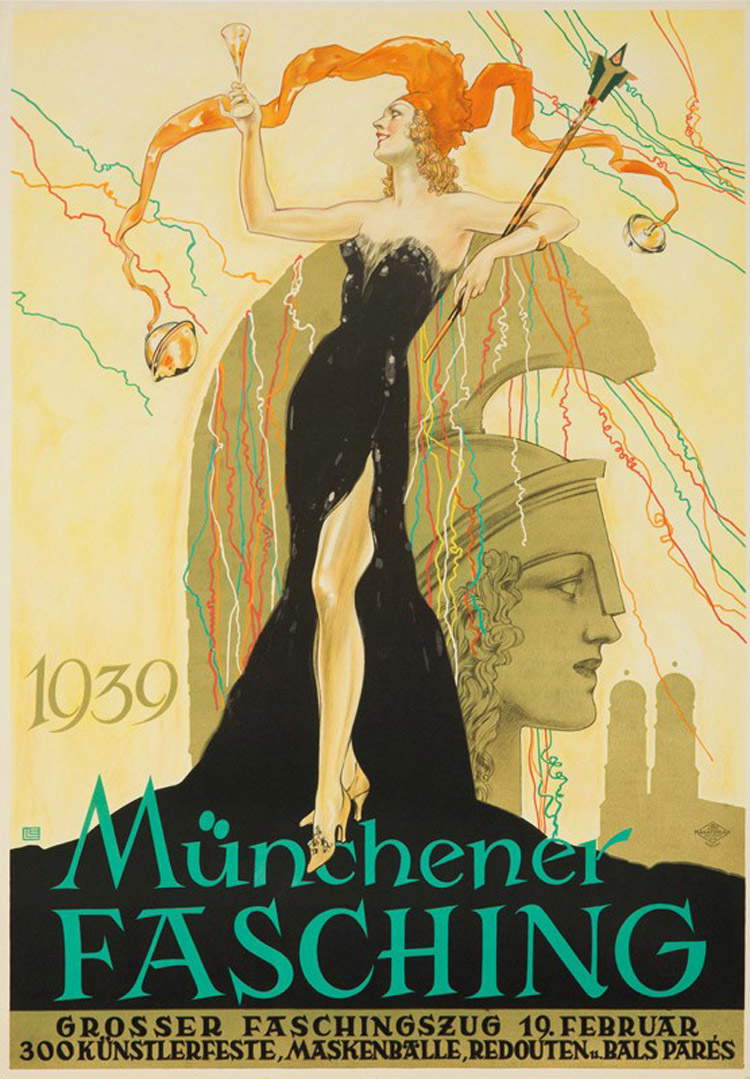

There are also numerous posters designed for public bodies, for which they usually entered rather competitive contests. Repeatedly returning to an amused sensuality are highly visible posters such as those made to promote the great Carnival festivals (a subject repeatedly retraced and a great passion of Lutz’s) that were held in Munich in the 1930s, such as that of February 19, 1939, where a seductive redhead, sheathed in a black dress with a deep slit (almost a foreshadowing of the mythical Gilda who would shortly later be played by Hayworth), lightheartedly and cheerfully raises her glass in front of the strict profile of Athena. And while it is certainly more composed than the beautiful cobalt blue poster for the 1936 Summer Olympics in Munich, it is only for reasons of status (in the same year the Führer will make a resounding image investment in the Berlin Olympics); again, albeit veiled, it is a celebration of seduction as a prize for the victor, a soft femininity contrasted with the virginal rigor of the classical model, whose solemnity is softened by a graceful Winged Victory in a light dress, holding flower crowns of Pre-Raphaelite evocation. But there are not only extraordinary women in Lutz’s imagery. The following year, the campaign promoting summer vacations in Germany shows us a blonde girl next door, the typical wholesome, Aryan beauty with her hair disheveled by the wind, walking through fertile fields and sun-drenched landscapes picking flowering branches. Women, in short, he seemed to love them all.

|

| Lutz Ehrenberger, Hexensabbath in der Friedrichstrasse, illustration for Lustige Blätter (1914) |

|

| Lutz Ehrenberger, Illustration for Eau de Cologne 4711 (1929) |

|

| Lutz Ehrenberger, poster for the Munich carnival (1939) |

Lutz’s women

Elegant, folksy, reassuring or emancipated. Naive or perturbing, or even better naive and perturbing. The Tyrolean peasant woman dancing with her fiancé and the kinky tamer readying her whip, the half-naked hunter in a walking cap and the lady powdering her nose in the mirror, uncovering her back in a head-turning play of viewpoints. The dreamer, the matador, the many and many dancers, the langelo of soldiers and the temptress who picks them up, those who board the streetcar and those who cruise, the sportswoman and the singer, the distracted and the lammiccante, the one who rejoices in the return of spring and the one who opens her fur over her garter. Flirtatious or cheeky, budding youths or seafaring ladies, Ehrenberger’s women move in leisure settings, never working, not tending to the house or children, but to curls and booties, love confidences, whispered promises. The many cups raised to toast, the tables of restaurants, cafes, luxury ships; the Carnival parties and Christmas greetings, the endless nights with theatrical exits and theatrical entrances to the ball, the balloons, streamers, sequins, pointed nipples, heeled booties, veils, feathers, mid-thigh stockings, silks that wrap around the hips. All are living well, all have a smile, hinted or cheeky, radiant or mischievous. But all of them, really all of them, love to be loved, are not objects but subjects of a shared desire, women who dress and undress to please and to like themselves.

In 1942, following the devastating effects of World War II in Germany, Ehrenberger returned permanently to Saalfelden where he quietly spent his last years, surrounded by the affection and a kind of devotional admiration of his flesh-and-blood women: his wife Lydia, her sister Elvira, who had moved in with them, and his young secretary. His work continued intensely, almost to the end, as the last major group exhibition, in which he participated with a work depicting Cleopatra, was the Grosse Wiener Kunstausstellung of 1949. He died in 1950, at the age of seventy-two.

When Lydia, too, leaves, after still cradling the memory of her love for twelve years, her last words are the lech of a happy memory, and she bids farewell to her loved ones by saying that she was happy, because Lutz had given her all that life could offer. Perhaps, deep down, she knew she was always just her, the woman a thousand times drawn and dreamed of, light and powerful as paper, immortal as seduction.

|

| Lutz Ehrenberger, poster for the Munich event for the Berlin Olympics (1936) |

|

| Lutz Ehrenberger, Sommer in Deutschland (1937) |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.