Domenico Guidi's Dream of St. Joseph: the other theatrum sacrum of Santa Maria della Vittoria

The story of the Capocaccia chapel, which opens in the right transept of the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome, just opposite the Cornaro chapel that houses Gian Lorenzo Bernini’sEcstasy of Saint Theresa, also includes a violent altercation between Luca Capocaccia, wealthy merchant as well as brother of the commissioner Giuseppe and his executor, and one of the artists involved in the decoration, the great Giovanni Battista Gaulli (Genoa, 1639 - Rome, 1709), better known as the Baciccio. The episode is recounted by Raffaele Soprani in his Lives of Genoese Artists. The wealthy Roman merchant, known for being “of the tenacious money saver,” laboriously set a price with the Genoese artist, who was supposed to take care of the decoration of the vault: when Baciccio presented him with the draft, however, Capocaccia told the artist that he should consider it included in the agreed sum. The painter went into a rage: he “charged Capocaccia with bad words, kicked the easel, made pieces of the draft, nor did he ever want to hear about that work again.” The commission therefore passed to the lesser-known Bonaventura Lamberti (Carpi, 1651 - Rome, 1721).

More accommodating must have been the artist in charge of the marble group that was to decorate the altar: the task of making it was entrusted to the Carrarese Domenico Guidi (Torano di Carrara, 1625 - Rome, 1701). Work began in 1695, shortly after the death of Giuseppe Capocaccia, who had drawn up his will on August 21, 1694, and had indicated brothers Luca and Michelangelo as executors. The chapel was to be dedicated to the eponymous saint, St. Joseph, and it would fall to Guidi to create a group depicting the Dream of St. Joseph. However, we do not know which precise dream the work refers to, namely whether it is the one in which the angel announces to Joseph the future birth of Jesus, or the one in which he urges him to flee to Egypt so as to save his son from the slaughter of the innocents. It is likely to be the latter, given the peremptory gesture of the angel, who points the index finger of his right hand in front of him. The episode is recounted in Matthew’s Gospel (2:13-15): “After they had departed, an angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream and said to him, ’Arise, take the child and his mother, flee to Egypt, and stay there until I tell you; for Herod is about to seek the child to put him to death.’ He therefore arose, took the child and his mother by night, and withdrew to Egypt. There he remained until the death of Herod, that what was spoken by the Lord through the prophet might be fulfilled, ’Out of Egypt I called my son.’”

Giovanni Battista Contini (Montalcino, 1642 Rome, 1723) was entrusted with the architectural project, and he intended to replicate the scheme of the Cornaro chapel by taking up all its essential elements: it is not known whether the choice was autonomous or dictated by the commission, but we do know that the Carmelites of Santa Maria della Vittoria would have liked an altar capable of “responding”, in some way, to that of the Cornaro chapel. Thus, as in the Bernini chapel, also in the one designed by Contini we find an altar that follows a convex line, is framed by coupled columns and is surmounted by a tympanum that is also curvilinear, and in the same way we find the two side panels, as well as the same chromatic choices, founded on green and red, and again the identical layouts of all the decorative elements, from the marble inlays of the back wall to the elements of the vault. The reliefs to be placed on the side walls were taken care of by the Frenchman Pierre-Étienne Monnot (Orchamps-Vennes, 1657 Rome, 1733), who, with his Nativity and his Flight into Egypt aimed at completing coherently, with Guidi’s group as an intermediate episode, the cycle dedicated to the paternity of St. Joseph, had awaited his first important commission in Rome and had obtained good feedback: we know, from the Lives of the Perugian Lione Pascoli, that Luca Capocaccia (who, moreover, was related to Monnot: one of his nieces had married the artist) was delighted with the side reliefs, and favorable comments also came from many who saw the two works.

|

| Domenico Guidi, Dream of Saint Joseph (1695-1699; white marble; Rome, Santa Maria della Vittoria, Capocaccia Chapel). Photo: Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| The Dream of Saint Joseph in the Capocaccia Chapel along with one of Pierre-Étienne Monnot’s panels. Photo: Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| The group in detail. Credit |

If Pascoli delves into a detailed account of the process that led to the creation of Monnot’s reliefs, the same cannot be said for the Dream of Saint Joseph. On the contrary: the writer and art collector launches into less than flattering remarks about the Carrarese, whom he decides to give prominence in his Lives, despite the fact that he considers him a “mediocre,” because in his opinion he would “approach excellence” in some of his achievements. The list of achievements mentioned by Pascoli also includes that of the Capocaccia Chapel, which in the course of history has obtained admittedly mixed comments: but it should be reiterated that against Guidi’s group plays the merciless direct comparison with Bernini’s Saint Theresa, which has always vitiated the judgment of many art historians. Vittorio Moschini, for example, wrote in 1923 that Guidi’s group “appears awkward and heavy with matter, and all the more so in the face of that miracle of flammeal vision which is Bernini’s Saint Theresa.” Even earlier, in 1829, Emanuele Gerini had determined that “Bernino’s Saint Theresa wins long in comparison with Guidi’s work.” In the same vein, five years earlier, Carlo Fea: “the statue of St. Joseph in the Crusade is by Domenico Guidi, who wishing to contrast with Bernino’s work, which stands before him, representing a similar subject, had naturally to stand below him, although it does not lack merit.” Of course, it will appear obvious to anyone that, from such a “challenge,” the Apuan sculptor can only come out the loser: but it is not necessarily the case that the story of a vanquished cannot nevertheless arouse a certain interest, especially if “it does not lack merit.” Not least because nowadays it is clear Domenico Guidi’s role as an “anti-Berninian” alternative capable of exerting great influence on many artists, especially on the French who came to the capital of the Papal States and, after the demise of Alessandro Algardi, as the major sculptor (along with Ercole Ferrata and Antonio Raggi) in late 17th-century Rome.

For the Dream of Saint Joseph, Guidi imagines a solution not too different from Bernini’s, though clearly less spectacular. His Saint Joseph sleeps seated, leaning with his right elbow on a ledge. The shirt opens in angular folds that somewhat conceal the saint’s body, but the details that instead show themselves to view denote a very careful study of anatomy: the fold of the brachial muscles near the elbow and the line of the pectorals are eloquent demonstrations of this. Remarkable, then, is the rendering of thefacial expression, which clearly suggests that Saint Joseph has fallen into a deep sleep: a sleep during which the saint will see the angel appear, who is already coming over to Saint Joseph’s left and with his right arm begins to gently shake the father of Jesus. The angel is distinguished by its classical profile: it is profoundly different from Bernini’s. Domenico Guidi’s Baroque is in fact more tempered than Bernini’s and indulges in a classicism that connotes his stylistic signature and that, in the case of the Capocaccia chapel, probably prompted the patrons to choose the artist from Carrara because of similarities in taste. All the artists chosen by the Capocaccia family were in fact united by a convinced adherence to a classicist interpretation of Baroque art.

|

| Alessandro Algardi, Saint Michael (ca. 1650; bronze, height 74 cm; Bologna, Musei Civici d’Arte Antica) |

The derivation of Domenico Guidi’s angel, for that matter, is quite clear: pose, attitude and especially profile of the face seem to derive from the Saint Michael by Alessandro Algardi (Bologna, 1598 Rome, 1654), after Bernini the greatest Baroque sculptor active in Rome, also a proponent of a classicist and composed line, and above all a master of Domenico Guidi. Moreover, Domenico Guidi himself took part in the casting of the work, in bronze: it is a late sculpture by Algardi, to which the Carrarese gave his contribution shortly after moving to Rome and entering the workshop of the well-known Bolognese sculptor. Again, another sculpture to which the angel would seem to refer is the Funeral Monument of Louis Phélypeaux de la Vrillière, which the Torano artist sculpted between 1677 and 1679 and which is in the church of St. Martial in Châteauneuf-sur-Loire: again, the pose of the angel would seem to have been kept in mind for the group in the Capocaccia chapel. An expert on Domenico Guidi such as Cristiano Giometti then emphasized the affinities between Domenico Guidi’s art and that of Carlo Maratta (Camerano, 1625 - Rome, 1713): a further precedent for the angel appearing to St. Joseph could in fact be identified in the angel at the feet of the Madonna in theImmaculate Conception painted by Maratta for the church of Sant’Agostino in Siena between 1665 and 1671. For Giometti, the pose of Guidi’s angel “blatantly traces” the bearing of Maratta’s.

|

| Comparison of the divese angels: on the left, that of Domenico Guidi’s Dream of Saint Joseph. In the center, that of Domenico Guidi’s Funeral Monument of Louis Phélypeaux de la Vrillière (1677-1679; white marble, height 245 cm; Châteauneuf-sur-Loire, St. Martial Church); on the right, that of Carlo Maratta’sImmaculate Conception (1665-1671; oil on canvas, Siena, Sant’Agostino). |

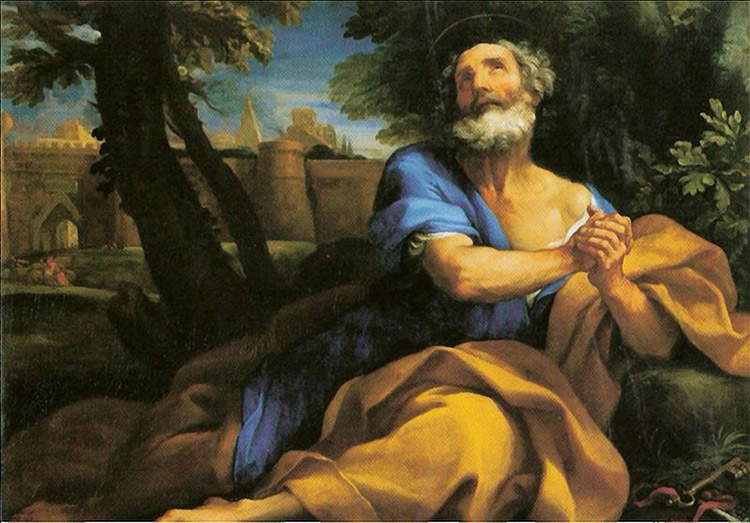

And to a certain extent Marattesque would also seem to be the Saint Joseph: here the reference, according to Giometti, is the Saint Peter the Penitent, circa 1670, kept at the National Museum of Capodimonte in Naples, which with its “tunic open on the chest,” the “cloak that wraps his left leg with ample drapery,” and the posture that “seems almost identical,” may have inspired the Carrarese. But the figure of St. Joseph also seems to refer to precise precedents that sprang from Domenico Guidi’s own chisel: a St. Joseph caught in a similar pose, that is, seated and leaning on his arms, is present in a celebrated masterpiece by the artist, the Holy Family with St. Zachariah, St. Elizabeth and St. John, a marble altarpiece in the church of Sant’Agnese in Agone in Rome, dating from 1676. Around the same time, however, is another work in which we glimpse a figure similar to the Saint Joseph of Santa Maria della Vittoria: it is the group known as La Renommée, which Guidi sculpted between 1677 and 1686 for the Palace of Versailles (Guidi was always on excellent terms with French artists, and the opportunity to execute this work arose after the artist, who had become director of the Accademia di San Luca in the 1970s, appointed Charles Le Brun an honorary member, and his French colleague, probably to thank him, got him the prestigious commission). In the Renommée group, named for the female figure that stands out at the top (the Renommée is Fame), we note that the allegory of Time, depicted as a winged old man holding a clypeus with the profile of Louis XIV, shows a marked resemblance to the Saint Joseph of the Capocaccia Chapel. But an important precedent is undoubtedly set by Bernini’s Saint Theresa: this is especially noticeable in a sketch for the Dream of Saint Joseph preserved in Pittsburgh. In this small terracotta, the pose of the saint is similar to that of Bernini’s Teresa, and the rock is reminiscent of the cloud that carried the Spanish mystic in the masterpiece of the Cornaro Chapel: however, Guidi had to have second thoughts when making the marble group, opting for a more measured and classical sculpture.

|

| Detail of the figure of Saint Joseph in Domenico Guidi’s group. Credit |

|

| Carlo Maratta, St. Peter Penitent (ca. 1670; oil on canvas, 105 x 139 cm; Naples, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte) |

|

| Domenico Guidi, La Renommée or History Writes the Deeds of Louis XIV (1677-1685; white marble, height 290 cm; Versailles, Musée National). Credit |

|

| Domenico Guidi, The Holy Family with Saint Elizabeth, Saint Zachary and Saint John, detail of the figure of Saint Joseph (1676-1685; white marble, 491.52 x 190.65 cm; Rome, Sant’Agnese in Agone) |

Of course, there were many commentators who greeted Domenico Guidi’s group positively: the example of a fine connoisseur such as Francesco Milizia, who included the sculpture among the “works that in Rome do him honor.” Admittedly: this is a sculpture that, according to many, has certain flaws, for example in the draperies (which, in any case, we have to imagine were largely executed by workshop assistants, given the artist’s advanced age), but it is a work of sublime quality, which fascinates the visitor to Santa Maria della Vittoria and stands as an entirely consistent crowning achievement at the end of the career of one of the greatest artists of the seventeenth century. Not bad for an artist over seventy years old who, with this masterpiece, worthily closed his glorious artistic career.

Reference bibliography

- Cristiano Giometti, Domenico Guidi (1625 - 1701), L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2010

- Cristiano Giometti, A Studio and its Sculptors. The inventories of Domenico Guidi and Vincenzo Felici, Edizioni Plus, 2007

- Gerhard Wiedmann, Baroque Rome, Jaca Book, 2002

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.