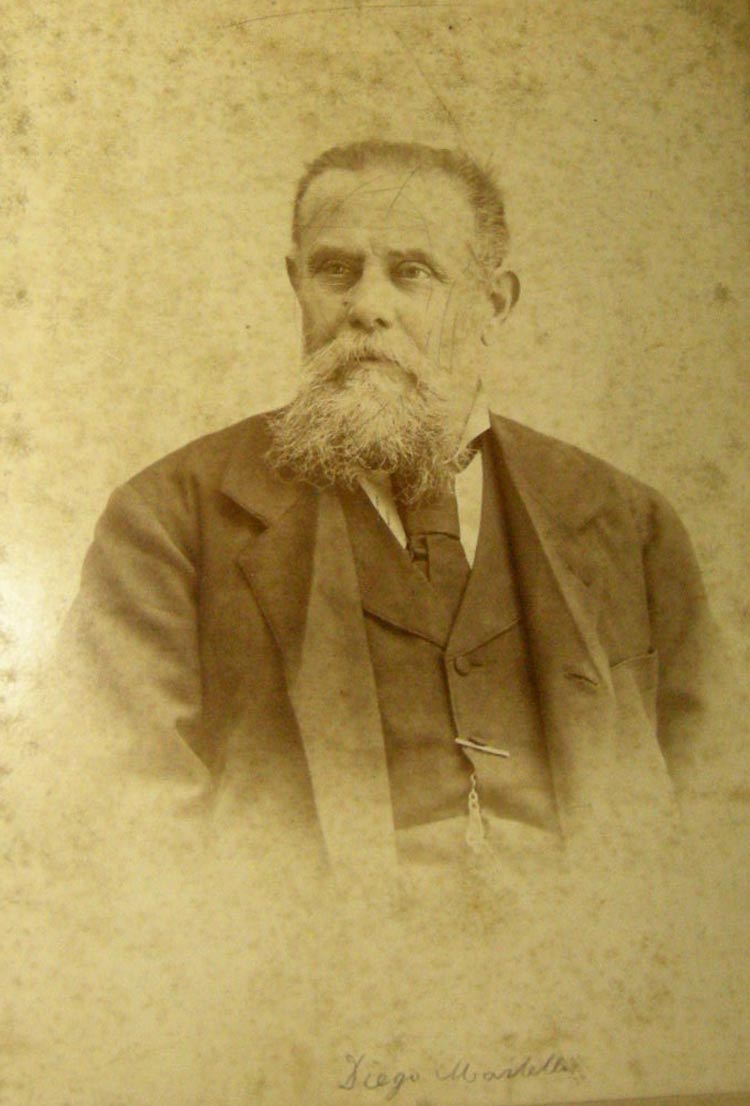

The great season of Macchiaioli painting probably would not have been as successful without Diego Martelli (Florence, 1839 - 1896), an extraordinary figure of art critic who left his picture gallery to the city of Florence (a collection that shaped one of the most substantial nuclei of the Gallery of Modern Art in the Pitti Palace) and his collection, consisting of 55 manuscripts, a library of 3.000 pamphlets and volumes and to which was aggregated the Florentine library of Ugo Foscolo (Martelli’s mother was in fact the niece of Quirina Mocenni Magiotti, the woman loved by the poet, although today the Foscolo collection is kept at the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale in Florence), and a correspondence of 5.000 letters, to the Marucelliana Library in Florence, by his own testamentary will: “I bind my Library and my autographs to the Marucelliana Library of the City of Florence... As for my manuscripts and autographs owned by me and the books of my library they will be delivered at once, and the autographs will be placed in sealed envelopes that will be opened only twenty-five years after my death.”

Diego Martelli dedicated his entire life toart. Coming from a wealthy family, Martelli studied natural sciences at the University of Florence, but his real interest lay elsewhere: he had thus taken to frequenting, not even eighteen years old and thanks to the intermediary of the painter Annibale Gatti, a family friend, the Caffè Michelangiolo in Florence, which since about 1855 had become the meeting place for young painters who intended to change the fortunes of art, break away from academic painting and propose a new approach to truth, with an eye toward the novelties coming from the France of Corot and Courbet. In this context, Martelli made friends with many artists destined to become prominent exponents of macchia painting: Telemaco Signorini, Odoardo Borrani, Raffaello Sernesi. In 1861 his father died, and Diego inherited, in addition to the substantial liquid assets left by his parent, several pieces of land, including an estate in Castiglioncello, which immediately became the site of the Macchiaioli’s most innovative research: in fact, every summer, Martelli invited all his friends there, from Signorini to Silvestro Lega, from Giuseppe Abbati to Borrani, not forgetting Giovanni Fattori.

It was with Fattori that one of the strongest relationships within the Macchiaioli circle came into being. The Leghorn painter first went to Castiglioncello to see Martelli in 1867, in one of the most tragic periods of his life: he had just lost his beloved wife Settimia, who had passed away due to the worsening of the consumption that was afflicting her, and he was in a strong state of despair. Martelli met him in Florence and, having seen him in that state, thought he was doing a welcome thing by inviting him to his estate: Fattori accepted, and that was the first act of a friendship destined to last over the years, so much so that Fattori, in his memoirs, will remember Martelli as the only true friend he ever had. This is how he was described by Fattori: "Humanitarian feelings - republican, and honest socialist. His word was all love, and he instilled courage in those who approached him. He fought with Garibaldi to make this patri that now the subversives would like to undo. [...] He had a feeling of a strong artist and writer-and he was one of the strongest art critics by founding the Gazette of the Arts of Drawing. He was always attending my studio helping me for advice, and making me a true and strong artist, without courtier praise, and foolish, but critical, and just praise to which he always lent a benevolent, and grateful ear. But everyone esteemed him, and loved him. He had eccentricities to which I too had my share - without realizing I had them (well intended).

In Castiglioncello, the Macchiaioli could find the quiet they needed to paint the beauties of the Tuscan coast and the humble daily life of the inhabitants, caught up in agricultural activities: the critic Dario Durbè, to indicate the artists who participated in this temperament, spoke of the "Castiglioncello School." In the meantime, Martelli continued to keep abreast of what was new in international painting: in 1862 he traveled to Paris, developing, through reading Proudhon above all, his already well-established rationalist ideas and his ideals of closeness to the last, so much so that he planned to found a newspaper called Il Satana, as we learn from an autograph document preserved precisely at the Marucelliana in Florence. Instead, it was in 1867 that he founded the newspaper mentioned by Fattori, Il Gazzettino delle arti del disegno, which Martelli directed and financed, and which was the first real critical tool for promoting the painting of the Macchiaioli. "The Gazzettino, which offered readers biographies of contemporary Italian and foreign artists, reviews of exhibitions, debates and various chronicles,“ Fulvio Conti recalls, ”qualified itself on the one hand as an instrument of aggregation of the various realist schools that had arisen in various parts of the peninsula on the model of the Tuscan one, and on the other hand as a means of acquainting Italian painters with the new international artistic currents." Between 1869 and 1870 Martelli went to Paris twice more, the second time in the company of Teresa Fabbrini, who would later become his companion (the portrait Fattori made of her at the Castiglioncello estate is famous: today it is preserved at the Museo Civico in Livorno), and on his return he began to plan to enlarge the Castiglioncello estate, a decision that would turn out to be rash, because it entailed economic difficulties for him that forced him, in 1889, to sell that very estate so important to him.

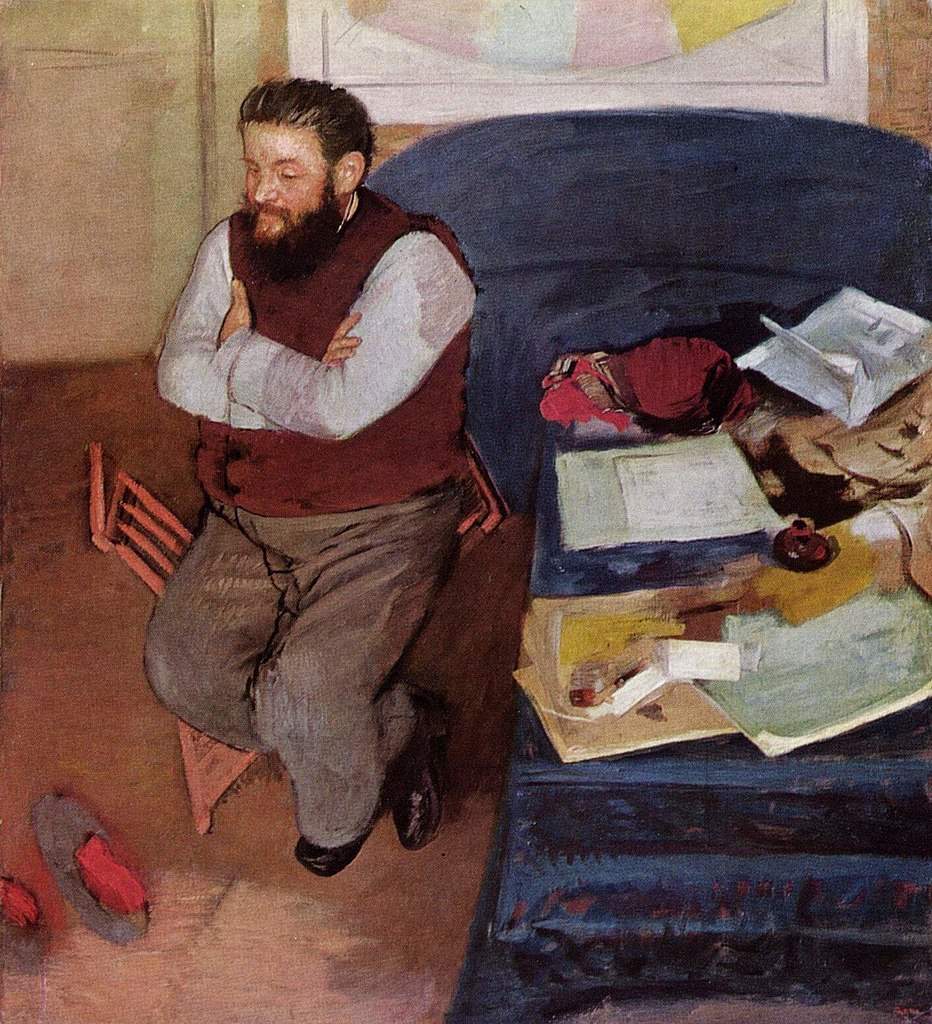

After an interlude in politics (he ran for the Chamber of Deputies for the “historical left,” without being elected, and would remain so in subsequent attempts), he returned to art and was among the first to notice the novelties of the Impressionists: in fact, during his last stay in Paris in 1878, Martelli had frequented the café de la Nouvelle Athènes in Place Pigalle, meeting several exponents of the movement, including Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, and especially Camille Pissarro. Martelli began to feel a deep admiration for him, to the point that he decided to support him and make his art known outside France. It so happened that the Florentine critic bought two paintings(La taille de la haie and Paysage - L’approche de l’orage) and, also in 1878, exhibited them in Florence: it was the first time that works of the Impressionist movement were seen in Italy. The Macchiaioli, however, did not welcome the Frenchman’s works: only Silvestro Lega and Signorini appreciated them, while the others, led by Fattori, believed on the one hand that they had arrived at the conclusions of the Impressionists before them, and on the other hand that their painting was defective for lack of drawing and strength (Lega and Signorini, on the contrary, admired their modernity and the originality of those fleeting outlines and vibrant brushstrokes). Returning from Paris, Martelli resumed his political battles (he was also a city councilor in Florence: his struggles included that to equalize the salaries of schoolmistresses, then municipal employees, with those of their male colleagues), and again tried to get elected to Parliament, always failing in his goal: he then continued his activity as an art critic, continuing to write articles but also organizing conferences where he presented the painting of the Macchiaioli and, on occasion, the art of the Impressionists as well. At the end of the 1980s, given also the difficult financial situation in which he had begun to find himself, he withdrew from artistic and political life. His precarious emotional stability was permanently undermined by the death of his Teresa in October 1895, and Diego passed away in Florence in November 1896.

Diego Martelli’s legacy has been preserved at the Marucelliana Library since 1897, and was enriched by a purchase in 2019: autograph manuscripts, personal library, and correspondence are available at the Florentine institute to delve into one of the most important figures in the history of 19th-century Italian art. His role, explains Luca Faldi, director of the Marucelliana Library, was first and foremost that of “animator of the discussions in the city (the location of the Caffé Michelangiolo, the symbolic place of his participation in the debates is located, marked by a plaque, on the same sidewalk of the Marucelliana, in the direction, for those leaving the library, towards the Piazza di San Giovanni), discreet guest of his painter friends in the ’house by the sea’ in Castiglioncello, mindful of the encounters he experienced in the paternal home frequented by Giuseppe Giusti, by historians like Atto Vannucci, by politicians like Vincenzo Salvagnoli, frequenter of the ’new’ artists and literati in the ’capital of the 19th century’ on three trips.”

Martelli also played an important role as a theorist of the movement, and left writings in which he summarized the intentions of the Macchiaioli movement: “They said that all the apparent relief of the objects depicted on a canvas is obtained by placing in the thing represented just the ratio between light and dark, and this ratio not being possible to represent it at its true value than by patches or brushstrokes that reach it exactly. This search was naturally to bring the consequence of a much rougher and more irregular workmanship than that of those who painted by bringing together all the so-called reshuffling with shading and brushwork, and as the eye like the palate is educated of different tastes, so while on the one hand they hunted down the sharp cries against the lack of execution, those who practiced them loved more and more a method that brought them quickly to the achievement of their goal and aroused more and more the finite a la Carlin Dolci, who became the prototype of gallows and gallows artists.” For Roberto Longhi, Diego Martelli had been the only Italian critic of the period who was truly modern and of international standing: he understood the originality of Impressionism, had modern ideas, and was directly involved in the promotion of artists having himself become their patron.

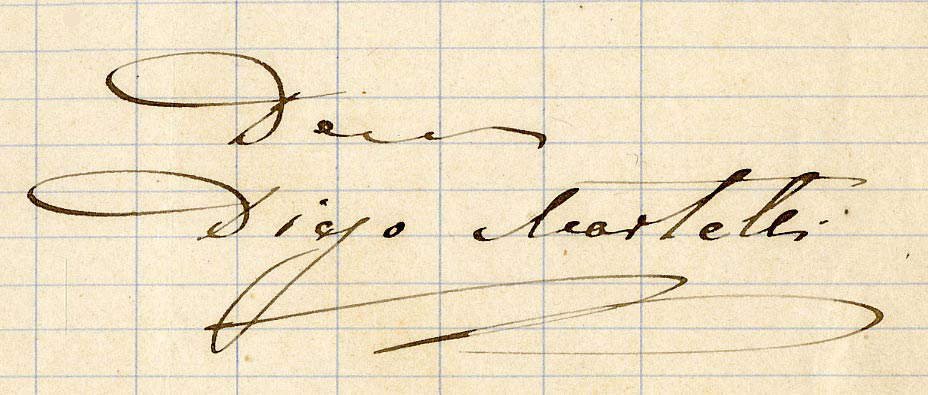

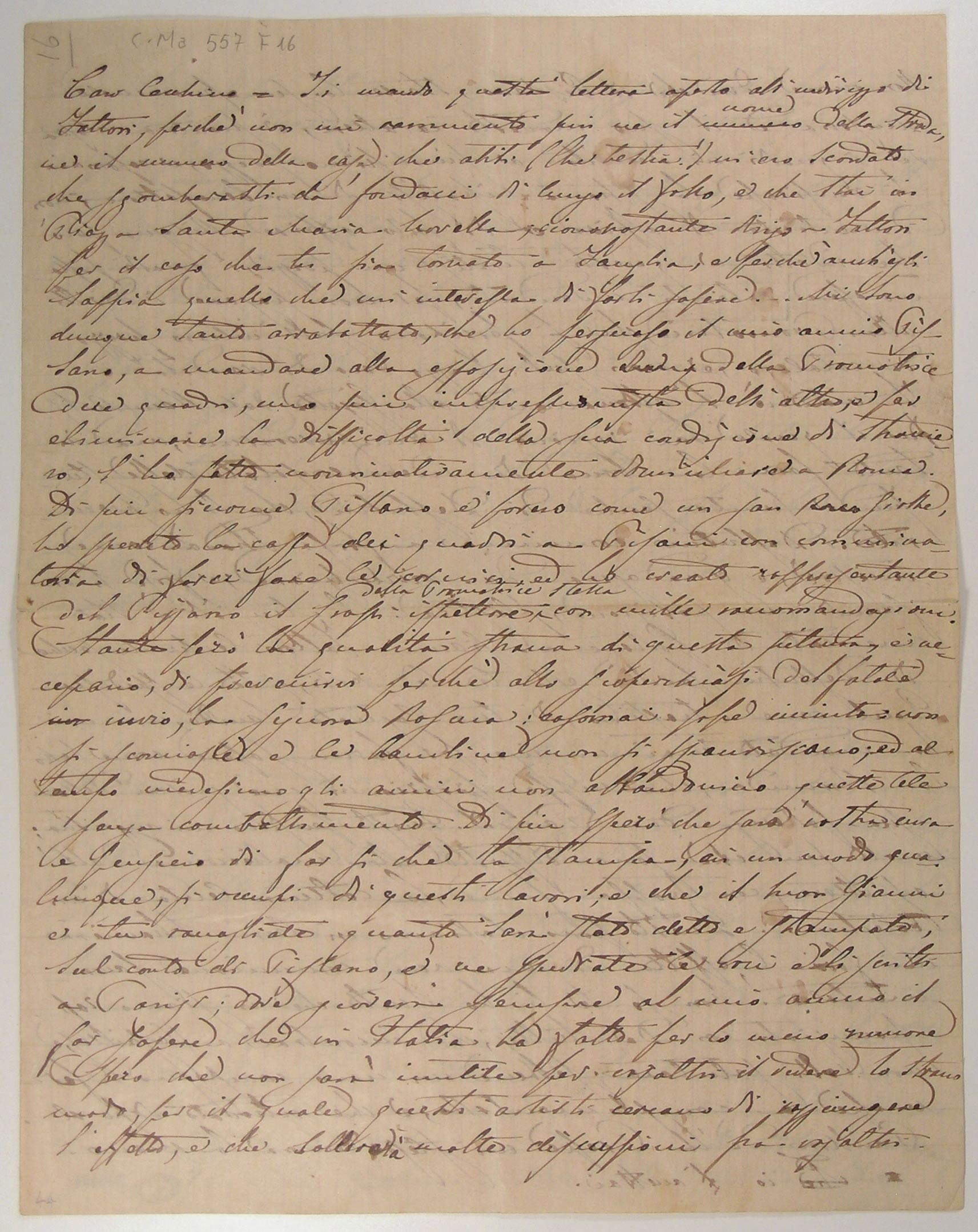

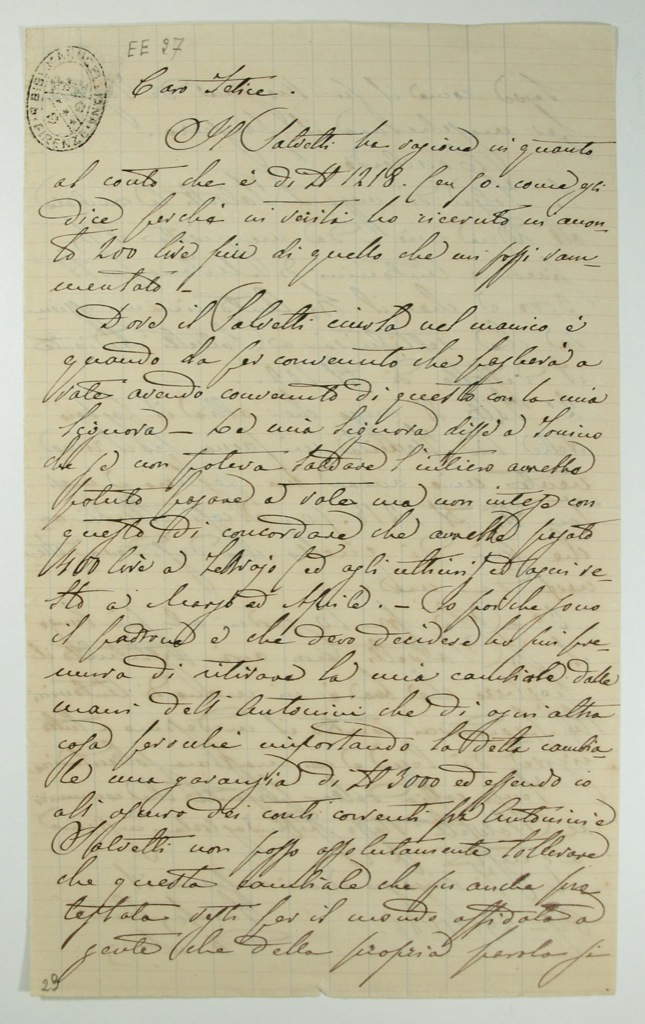

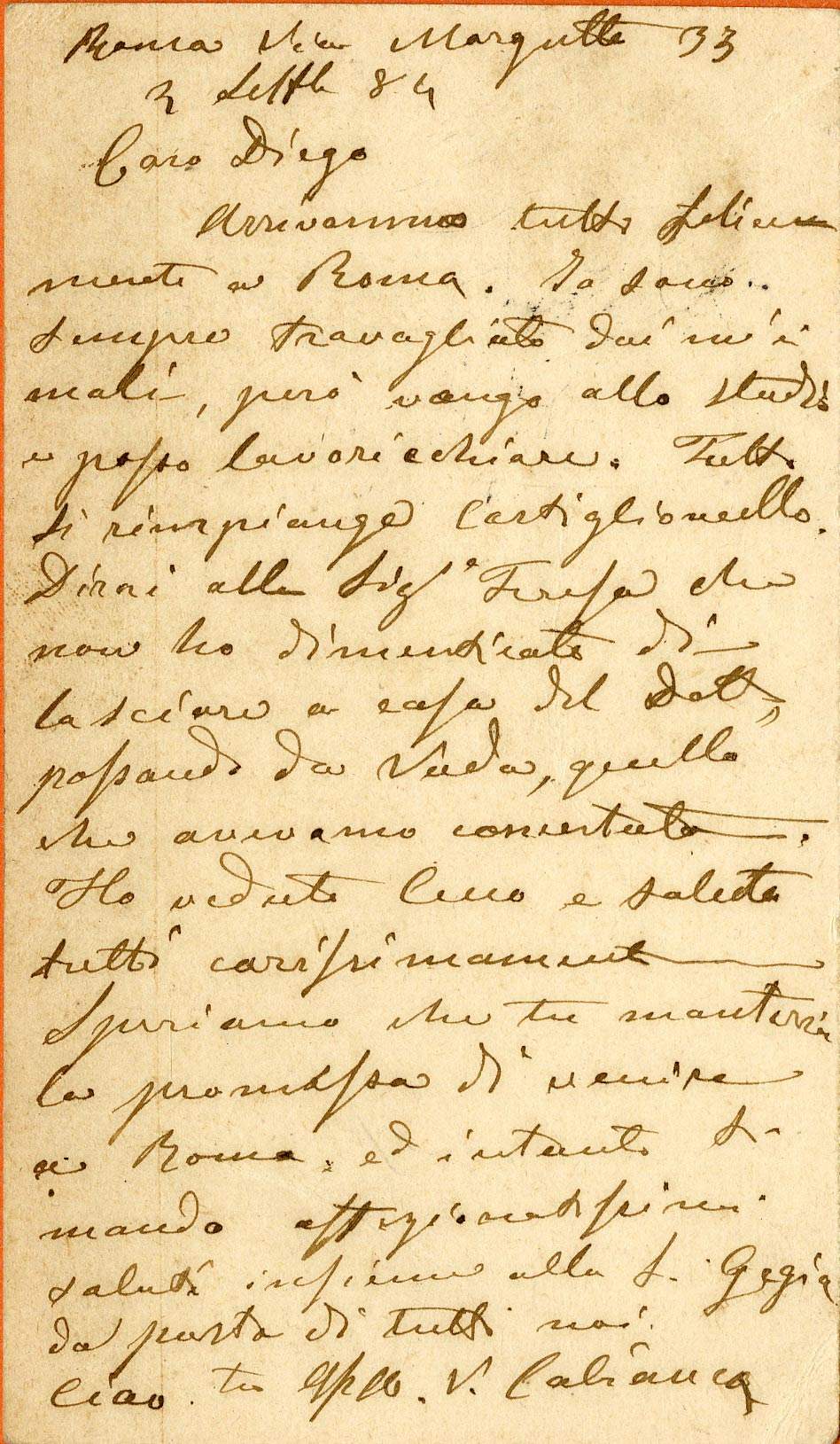

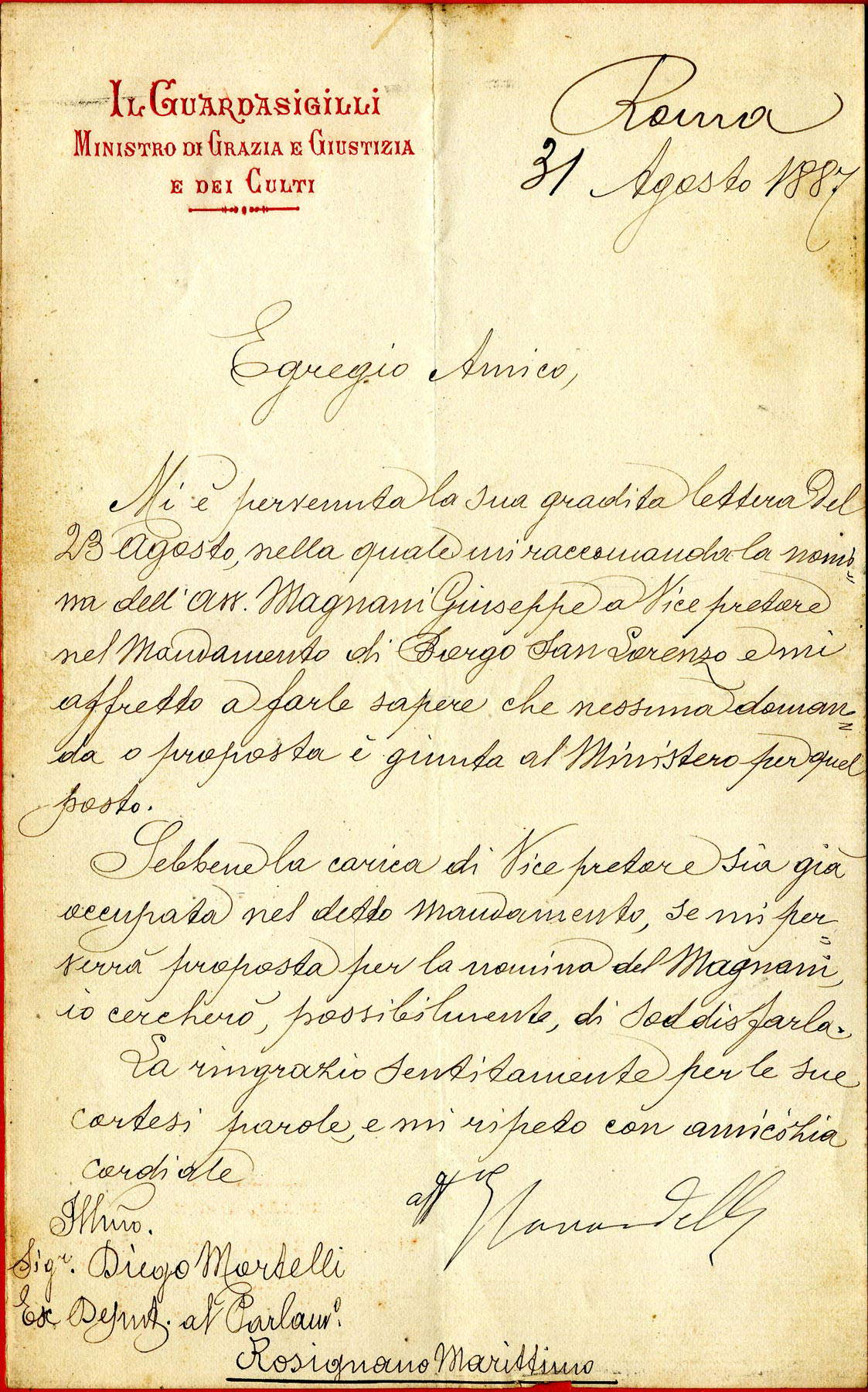

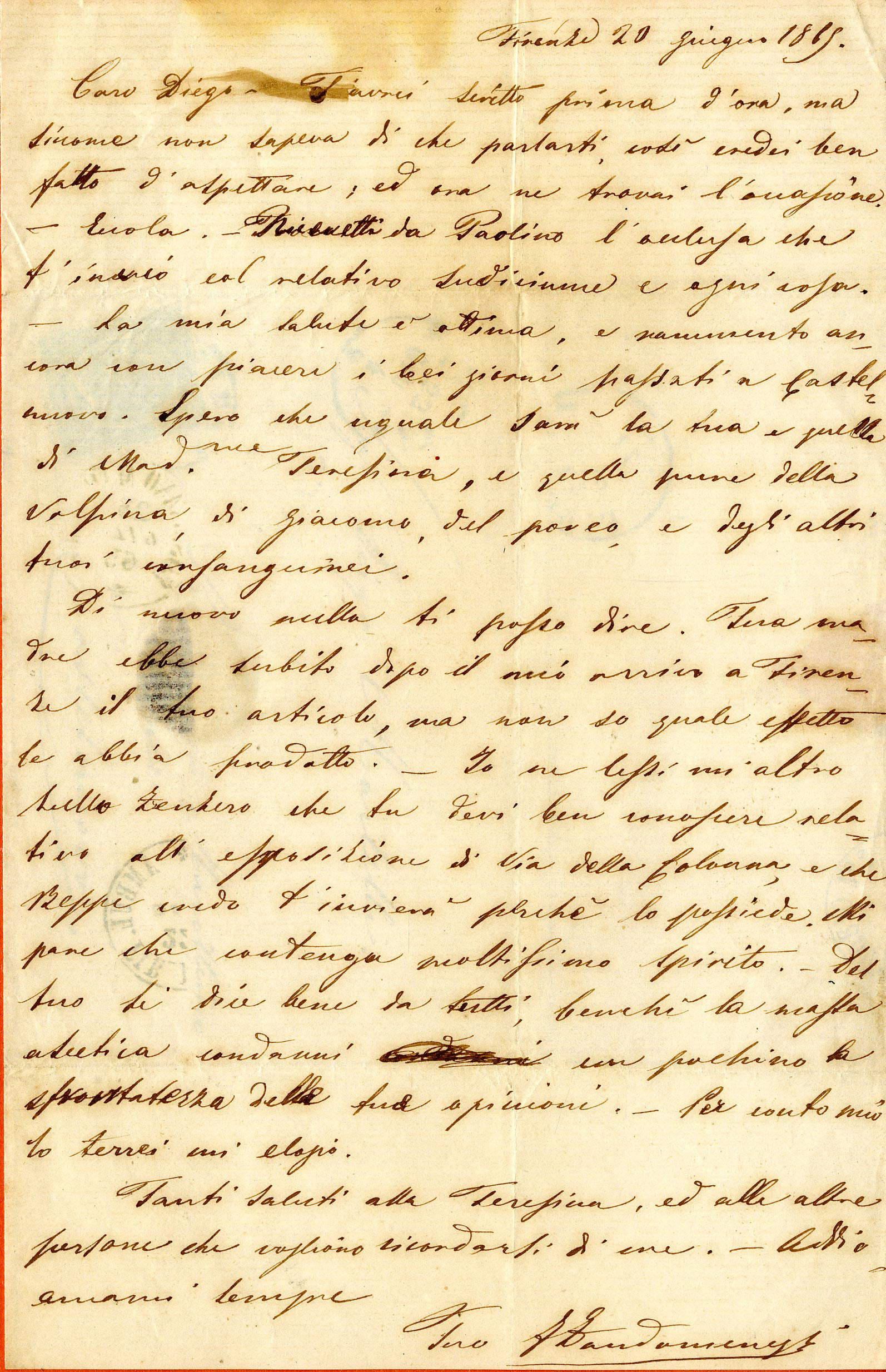

Diego Martelli’s list of correspondents includes all of his Macchiaioli friends (such as Francesco Gioli, Giovanni Fattori, Telemaco Signorini, Silvestro Lega) but also many literati and politicians from the progressive area, from Giosuè Carducci to Felice Cavallotti, from Giuseppe Zanardelli to Edmondo De Amicis. A list of personalities that, Luca Faldi explains, “restores of this Florentine a figure of an open and committed public man. Especially the latest purchase, which took place in 2019, of a correspondence that is imagined to be almost inexhaustible [and to which the three images published above refer, ed.] seems to confirm a project of existence in which, from art to politics, action should be animated by research , support, disclosure, and the proposal of ’more advanced balances.’”

The Martelli donation has a strong symbolic value for the Marucelliana: “it inaugurates,” explains director Faldi, in fact, “a procedure of increasing the documentary patrimony in the extra-bibliographic sector that has remained regular until now. If libraries preserve archives of personalities, the presence of author libraries at archives is less common. What is the reason for such ’generosity’? Not just a single service for the benefit of scholars and researchers, certainly, also based on the desire to increase the offer and provide occasion for more complete and in-depth investigations rather the conviction to ensure the transmission of the memory of figures recognized as a reference for the impact of their activity on the community. Saying yes to the gift of Diego Martelli, to the ’dear Diego,’ to the ’most esteemed Mr. Diego,’ to the ’dear friend’ (who is also a friend of the library) has opened a channel of access to other ’landings’ that are still in progress today, has inaugurated a ’long-lasting phenomenon’ potentially without temporal terms.”

The Marucelliana Library opened to the public on September 18, 1752, and bears the name of its creator, bibliophile Francesco Marucelli, who wished to leave to the public a library of general culture open to a wide range of users, as indicated in the inscription on the façade that reads “Marucellorum Bibliotheca publicae maxime pauperum utilitati.” The original nucleus of the collection consists of the library of Abbot Francesco, who, before his death in Rome in 1703, had stipulated in his will that his library be earmarked for the creation of a public library in Florence, where there was no such institution at the time. In 1783, under the direction of Angelo Maria Bandini, the drawings and prints collection of the last representative of the Marucelli family, Francesco di Ruberto, arrived at the Marucelliana. Other important acquisitions came to the Library following the Conventual, Grand Ducal and Napoleonic suppressions, as well as after the post-Unitarian suppressions in 1866 (it was precisely the latter increase that marked the entry to the Marucelliana of most of the cinquecentine and incunabula currently held). In the second half of the nineteenth century and in the first of the following century various historical, artistic, literary, and political collections such as the Martelli legacy, the Bonamici collection, the Nencioni correspondence, Industrial Art, and many others came to the Library. Following the law of 1910, which instituted the compulsory deposit of printed books, editions printed in the four districts of the province of Florence, Pistoia, San Miniato, and Rocca San Casciano began to arrive at the Marucelliana.

The holdings of the Marucelliana, a general culture and research library on a historical basis with a humanistic and artistic orientation, especially with regard to Florentine and Tuscan culture, consist of more than 596,000 volumes and pamphlets (including 488 incunabula and about 7,995 cinquecentine), 2.741 volume manuscripts and about 64,212 loose papers (autographs and correspondence of literary, historical, and artistic interest), an important and valuable collection of about 53,000 prints and 3,200 drawings (ranging from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century); 9,000 librettos of melodramas; and 9,638 periodicals including current and discontinued titles.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.