Defending the faith and protecting the Mediterranean: history of the Knights of St. Stephen

On March 15, 1562, theOrder of the Knights of St. Stephen was officially born: on that day, Archbishop Giorgio Cornaro, nuncio to Tuscany on behalf of Pope Pius IV, dressed Cosimo I dei Medici, then duke of Florence and Siena, in the robes of Grand Master of the Order, in a sumptuous ceremony held in Pisa in the presence of the most important representatives of the state. The institution played a very prominent role in the affairs of the Tuscan Grand Duchy throughout its existence, and it left an imprint that is still recognizable today in the urban fabric of several cities in which the chivalric order had its operational headquarters, including Pisa, Livorno and the Island of Elba.

The motivations that concurred in its formation are partly stated in the founding act, such as “the praise and glory of God and the defense of the Catholic faith and the custody and protection of the Mediterranean Sea.” But in all likelihood, these were joined by others of a political nature and crowning ambitions of the Tuscan lord.

In fact, it should be noted that the Order’s main function, that is, to fight Turks and Barbarians by sea, had already been ensured for several decades by the state navy, which as early as 1547 had the first galley built in Pisa and known precisely as the Pisana put to sea. The navy in those years had taken part in some well-known exploits and over time had seen an increase in means and men, but this had not prevented it from also cashing in on some bitter defeats. This was the case in 1554, when the captain of the fleet, Jacopo d’Appiano, who was supposed to stop the landing of the French army on the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea, had refused to engage in combat with an enemy of equal strength. And certainly this was not the only case in which the navy had distinguished itself by meager figures, and it had repeatedly had a way of demonstrating the inexperience of its men in the struggles against the Muslims, for example by having its crew massacred at theIsle of Gerba, where ships had stopped to resupply, leaving soldiers to disembark without precautions, or when three galleys, including the Capitana, which, however, was the only one saved, escaping near Giannutri from Algerian boats, ended up smashing against the coast.

However, Cosimo I did not want to abandon his hegemonic dreams on the sea, and perhaps that is why he thought of starting a new beginning, with a selected militia and officers who were finally trained and not collectivists. It has already been effectively pointed out, by scholars such as Furio Diaz and Cesare Ciano, that the availability of a fleet was expendable in the difficult balance with European powers, being able to offer its services upon request, for example to the king of Spain who needed it for his various engagements. The autonomy of the Order flying its own flag could also ensure less involvement of the Tuscan state when it became a protagonist or participant in questionable actions. Moreover, the banner of defending the faith could ensure prestige and military and mercantile advantages, and no less, ingratiate itself with the pope’s approval. In fact, in 1569, when the Tuscan state put the Order’s fleet at the service of the Holy League, Cosimo I was granted the title of Grand Duke of Tuscany through a papal bull issued by Paul IV. Finally, it should be pointed out that the Order presented itself as an aristocratic institution closely dependent on the Prince and his dynasty, allowing the Tuscan aristocracy to be held in a pact of loyalty to the sovereign.

The Order of the Knights of St. Stephen was modeled after the Sovereign Order of Malta, but differed from it in its relative autonomy, with the role of Grand Master in fact held by the rulers themselves. The Order was soon able to gain considerable prestige, both in the number of those ordained and in the accumulation of assets. If at its foundation there were sixty Knights to compose it, half of whom were Tuscan, by the first decade of the 17th century just under 1,400 men had taken the insignia of St. Stephen’s, most of whom came from other states. And while the institution initially supported itself on grand ducal munificence, it later became more independent economically as well through the income from various estates obtained through donations.

Practically from the beginning of their history, the Knights of St. Stephen had their headquarters in Pisa in the square that the Order itself takes its name from, Piazza dei Cavalieri, redesigned to a design by Giorgio Vasari. Here stood the Palazzo della Carovana, where members of the Order resided and trained through hard training that included a period ashore aimed at the practice of the liberal arts, religious and military, and one directly on the galleys; next to the residence is the church of Santo Stefano dei Cavalieri, where numerous war trophies such as insignia and flags torn from Islamic vessels are still kept, in addition to great masterpieces by Bronzino, Vasari, Cigoli and many others. While another nodal site of their operations was the port of Livorno, where the Order’s ships were stationed.

In the course of their centuries-long history, the Knights took part in numerous exploits: the first outing at sea was in 1563 to participate with the Spanish fleet in the expedition to rescue the fortress of Oran, besieged by the ships of the dreaded Turkish admiral and privateer Dragut. On their return, one of the galleys, the Lupa, which remained isolated, was attacked by two Muslim galleys, and in the clash several knights perished and the ship was eventually captured. Although the success was unsuccessful, the honor of the Tuscan military and their spilled blood was instead saved.

The knights took part in the relief contingent organized by the King of Spain in the epic battle that took place in the fortress of St. Elmo in Valletta, where the Order of Malta heroically resisted for months the siege of the Algerian Dragut fleet, which died in that very battle. Continuous were the sea battles of the knights, and it is also recalled with some hagiography the naval conflict between the Order led by Jacopo d’Appiano and the notorious privateer Caraccialì (or Carg-Alì), in a clash that according to tradition lasted a good seven hours, and then saw the Islamists beat a retreat, leaving two ships in Tuscan hands, with three hundred and ten prisoners, and two hundred and twenty Christians, previously kidnapped, thus ransomed.

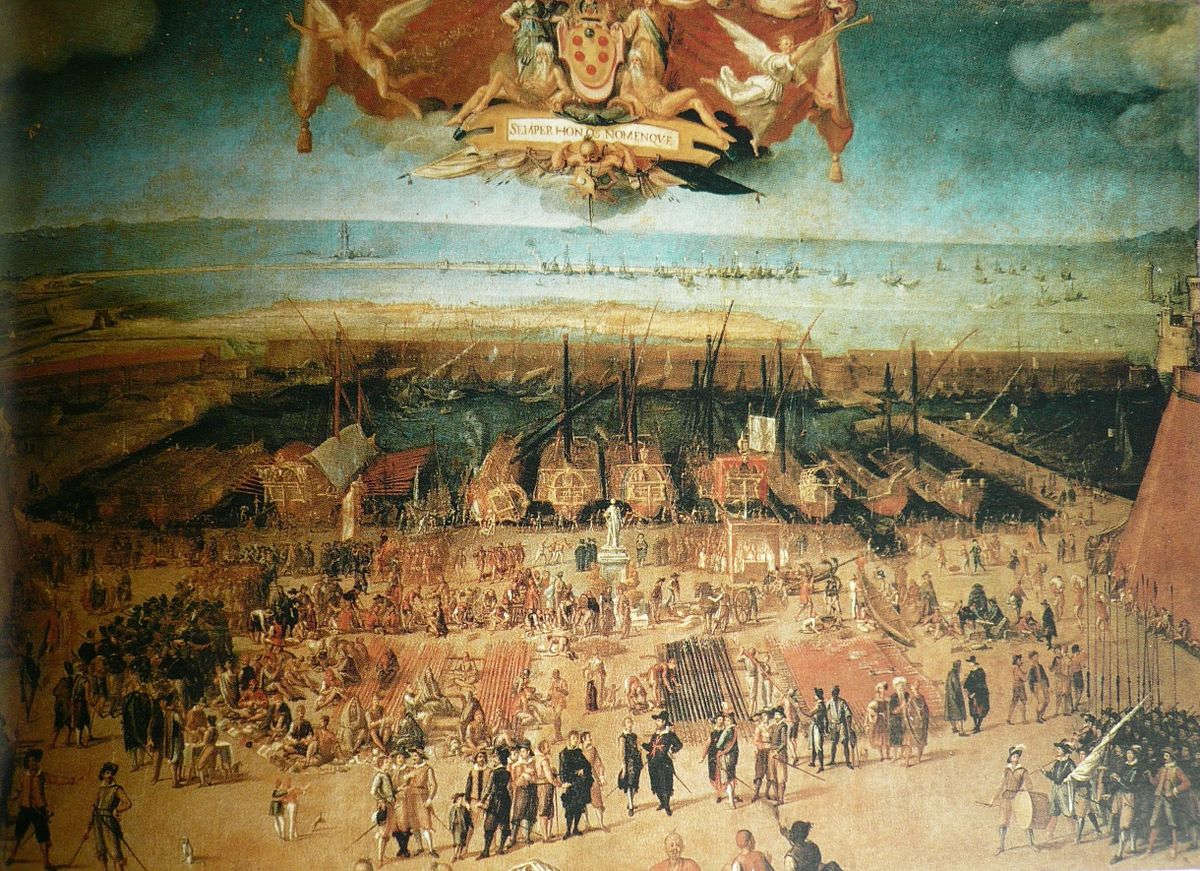

Even in what is celebrated as the most important naval victory led by Catholic armies against the Muslims, the Battle of Lepanto fought on October 7, 1571, the Tuscan state participated by providing twelve of the two hundred galleys involved, with over one hundred Knights of St. Stephen on board. The ships knew how to do themselves a fair amount of honor, engaging for the most part in major maneuvers and captures, including the recapture of a ship, the former Papal Capitana, previously taken by the Muslims.

After the historic victory, which downsized Turkish power on the sea, the Stephan galleys were mainly engaged in a fierce race war against Muslim and Barbary vessels. In short, the Tuscan fleet gained a reputation as a rapacious predator, which did not disdain, to tell the truth, even attacking ships and merchants protected by the Serenissima of Venice. But the list of exploits is still very long: in 1605, for example, Admiral Iacopo Inghirami distinguished himself by a remarkable action, leading five galleys to assault the fortress of Prevesa in the Ionian Sea, which attacked by surprise in the night was defeated and destroyed, with a considerable booty of goods and slaves as a prize. Fortune, on the other hand, did not befall Inghirami two years later in his attempt to reconquer Famagusta, but that same year he was able instead to celebrate the conquest of Bona on the North African coast. That action, celebrated by all of Christendom, earned the Tuscan Grand Duchy a large number of captured slaves, between 1,500 and 2,000, and bronze obtained from conspicuous artillery pieces, with which the statue of Ferdinand I in Florence’s Piazza della Santissima Annunziata and the Four Moors of the famous Livorno monument were cast. On those dates, Vanni d’Appiano d’Aragona also took part in an operation during which he seized three Tunisian brigs, on board of which was found the sacred image of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, the object of an earlier robbery, long revered and still kept in the church of Our Lady of Leghorn.

From shortly before the middle of the 17th century, however, the race war was increasingly disliked by the Tuscan ruling state, which saw it as an impediment to developing trade with the East. In the following years, in fact, these expeditions dwindled, and the navy was mainly engaged in escorting commercial products and prominent personalities, as well as in its usual role of vigilance and patrol along the Tyrrhenian coast. The next century would see the last sea battles, which ended in 1719 with the capture of three Barbary vessels off Sardinia.

With the waning of the House of Medici, the Order’s extraordinary season at sea came to an end, so much so that in 1744 the Stefanian commander Ugo Azzi recommended that at least one galley be sailed so that crews would not forget the practice: “li uffiziali e le marine si avviliscono, li schiavi diven fiacchi alla pratica del remo e l’altra ciurma si illanguidisce.”

In fact, from 1747, under the Lorraine dynasty, the Grand Duchy signed peace treaties with North African cities, causing the historic function of the Knights of St. Stephen to fade away. From there the Order was reorganized several times, particularly with the reforms of Peter Leopold, increasingly losing its function of sea combat, but becoming an effective tool for the formation of the ruling class of the Tuscan state. And amidst ups and downs, the institution continued to subsist even after the years of French occupation, while continuing to foster doubts about its usefulness.

The Order deprived of all its main purposes risked being suppressed again with the unification of Tuscany to the Kingdom of Sardinia, but this was only worthwhile on the alienation of its patrimonial property, since being a religious order founded “in perpetuity” by papal bull, it could only be disestablished at the discretion of the pontiff, and for this reason it still exists today, and its memory is kept alive by theInstitution of the Knights of St. Stephen, a moral entity operating in Pisa, which promotes publication and study activities.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.