Davide Benati, the poetry of a translocated nature that flourishes on a humus of paper and canvas

To visit an artist’s studio is to have the privilege of being invited into a secret garden, into which one must tiptoe so as not to disturb the subterranean germination of the works to come, which hover there in little more than a potential state. The sense of expectation one feels is an echo of their whispering oscillation between the ethereal realm of intuitions and the raw materials that will shortly thereafter give substance to their manifestation through the gesture with which the artist will trigger the encounter between these two dimensions. And never as in the case of Davide Benati (Reggio Emilia, 1949) is the simile of the garden appropriate, his studio being a place of incubation in which forms literally blossom, only to blossom by depositing themselves as a chromatic imprint on a humus of paper and canvas with which they share an elusive vegetable ancestry. For more than forty years, the artist, now the protagonist of an extensive solo exhibition at Palazzo da Mosto in Reggio Emilia that traces his career since the early 1980s, has based his inspiration on the forms of nature, which he has epitomized, synthesized and translated into a chromatic and lyrical elsewhere in which naturalism is only a distant reminiscence. Precisely on the occasion of this exhibition, Benati opened the doors of the studio to which he moved his work in 2020, located in Reggio Emilia on Via Emilia Santo Stefano, a pedestrian declination of the Roman artery connecting Rimini with Piacenza.

The artist goes there every day early in the morning, at the end of a walk that coincides with the route he took as a boy when, after a bus ride, he arrived from the countryside to the city to go to middle school. His creative process begins with this flânerie in sensitive auscultation of the signs inscribed in the things that fate or chance offer to the eyes, an attitude in him ancestral sharpened especially after his travels to the East, from which come the main agniptions underlying his poetics. The actual work begins when he opens the studio window to let in the air and light that make his visions come alive in space. “I always work in natural light, even when it’s not there,” Benati says, and the veiled glow of a winter morning floods the two paintings we find in the workshop antechamber. The first is a woodcut in oil and Nepalese paper on canvas from the series Segreta (1998), in which the black outlines of the mysterious entrance to a dark compartment emerge like an apparition from a vaporous reddish background, the same color as the robes of Buddhist monks. The drawing derives from the impression made in frottage of the entrance to a sacred altar he uncovered in a dilapidated alley in Kathmandu, the place that more than any other marked the fate of his creative adventure.

His fascination with Nepal dates back to the trip he made there in 1977 when, a teacher at the Brera art high school, in a moment of disorientation, he decided to look East as a reaction to his existential estrangement from the tense climate of the lead years and to seek a new direction for his art. Benati is the son of an omnivorous generation, which at that time in Italy was measuring itself against the conceptual poverists or analytical painters, engaged in reflection on the tools of painting and in the search for its degree zero, while from across the Atlantic came the powerful solicitations, of opposite sign, from Action Painting and Pop Art. Like his colleagues, the artist wanted to experiment as much as possible, and in this he was supported by the solid and multifaceted training he received at the art institute that initiated him into the secrets of all possible techniques, from watercolor and oil to fresco and wall tempera. The Academy he attended at Brera did not satisfy him; he found its teachings divorced from the most current issues in art, and in Milan, where he had moved in 1968, he tried to appropriate the techniques of the new artists he saw. But the beginning of the turning point is the memory of the Langlois Bridge in Arles painted by Van Gogh, seen as a boy in the catalog purchased by his father of the Dutch painter’s exhibition held in 1952 at the Palazzo Reale in Milan, in which the influence of Japanese art, which in the nineteenth century “clarified many ideas for young Western artists,” was strong.

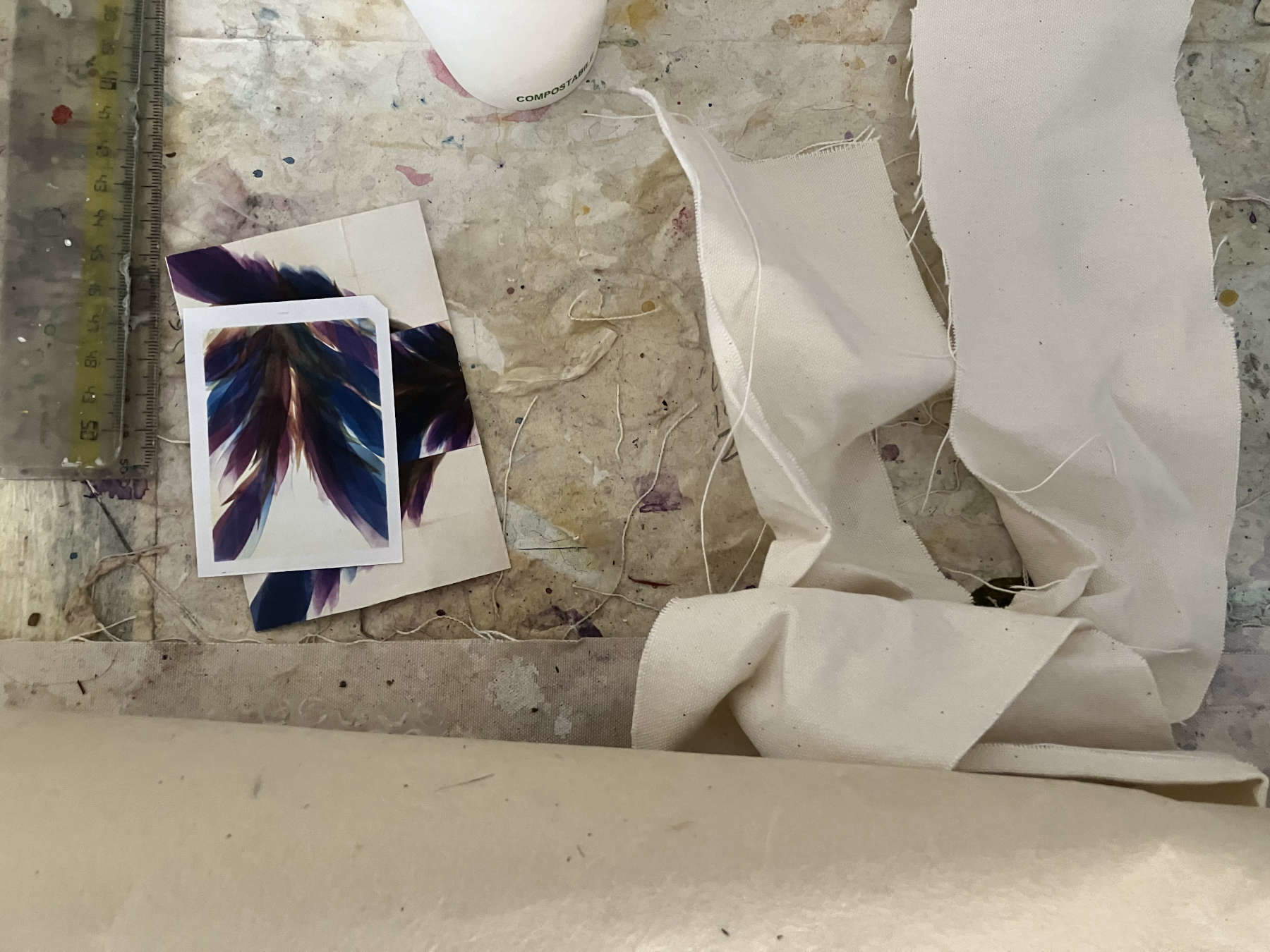

The concept that guides him in Nepal is that, never abandoned in all his later research, of still thinking that East-West bridge active and looking for signs of it in what he sees around him. And on that very first trip to Kathmandu (which would be followed by those in 1984 and 1995), along the way, in the stalls of souvenir hawkers, he encountered the paper that would revolutionize his artistic production, a poor material, used for parcels or for xylographic printing of modest calendars, but handcrafted with a very ancient technique from bamboo and rice fibers. He shows us an impalpable sheet of it, of a fine production now called “silk paper,” which the artist still buys from his trusted Nepalese vendors. It is almost transparent, of an atmospheric white that seems made to hold light, very light, woven with an irregular texture in itself presaging an infinite multitude of images. It is not a paper made for painting, not even watercolor paper, because it is very fragile when moistened and exhausted by color. That is why initially the artist dares to make only light, circumscribed marks on it, leaving the sheets free to float in the void “like sheets in the wind.” As time goes by, the intention to bring out the forms he glimpses within them becomes more precise in him, and for this he needs a support capable of accommodating more paint. From a certain point onward, therefore, the paper is glued in two layers on a canvas plastered and prepared with two coats of white, transforming itself into a kind of material glaze, like the “tonachino” of the fresco on which one must paint without second thoughts.

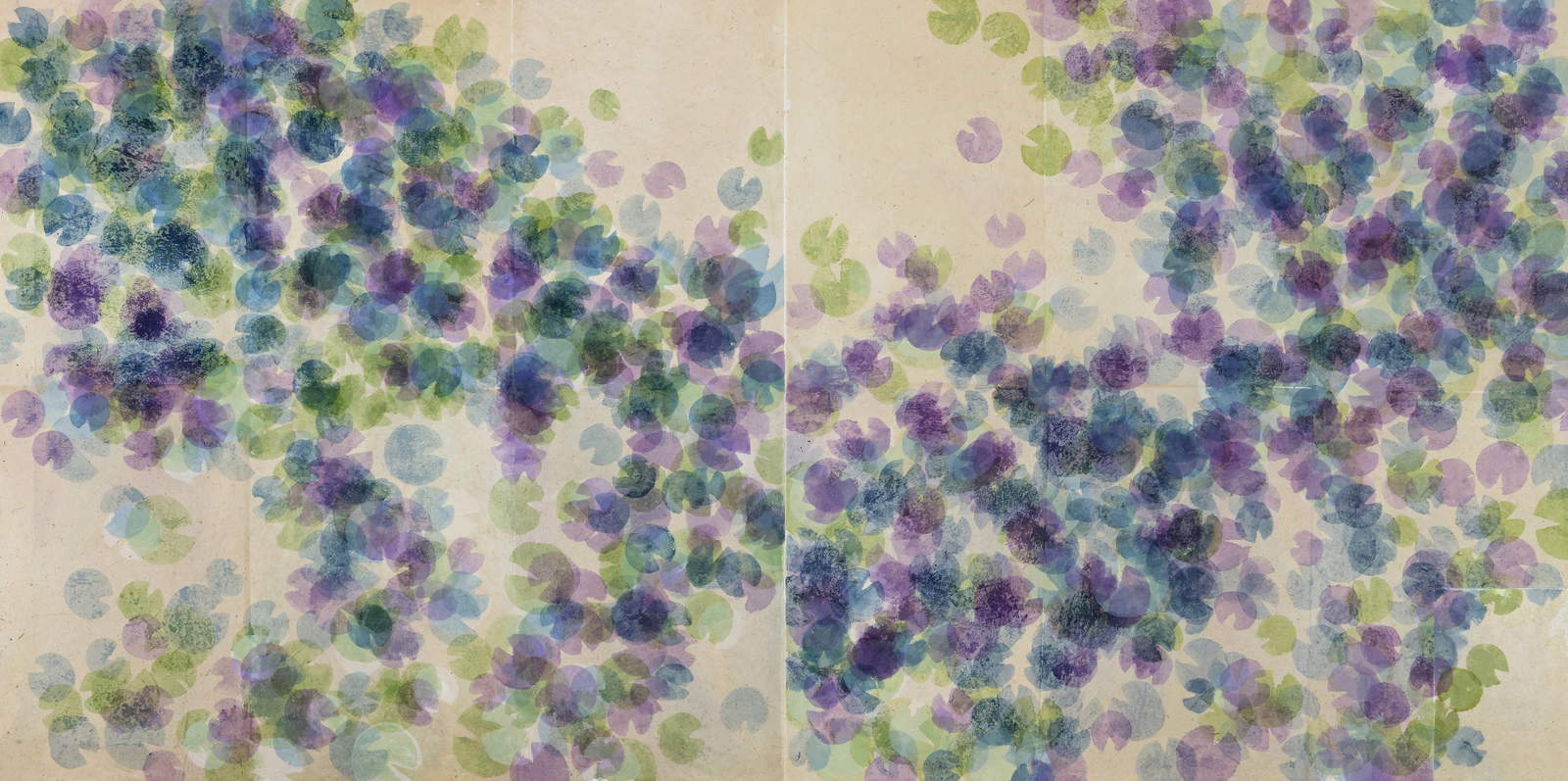

In the studio, brushed by a grazing light that detects its porosity and veins, we find a large canvas ready for painting leaning vertically against the wall, which in itself some might consider a finished work. To explore that fertile surface of happenings to come, Benati imagines painting the forms inherent in the texture of that distilled herbarium and begins to work on the repetition of nature’s silhouettes. Reinforcing the paper with canvas gives the images texture and depth; on that epidermis he can brush over it hundreds of times because the paper absorbs and behaves like a fresco. With this preparation, one gains the ability to superimpose watercolor transparently until it becomes a body, transforming a quick technique into a process that can be dilated for months, all the fading steps of which can be seen. It is as if the gaze penetrates the image in its more or less color-soaked veils and “tactilely” perceives its different degrees of saturation. In the meantime, the forms on the surface play and dance like musical notes, causing the reference to the naturalistic matrix to fade into a very elegant chromatic toning, which still ideally preserves the fragrance of nature. Calla lily flowers, water lily leaves, the pitted capsules containing poppy seeds and many other botanical species to be recognized then become the pretext for bringing ambiguous forms into the world, open to a plurality of readings. If a flower can be considered at once eye, sex, jellyfish or gaze, it is always unrepeatable specimen of absolute beauty in its being unstable and full of tension.

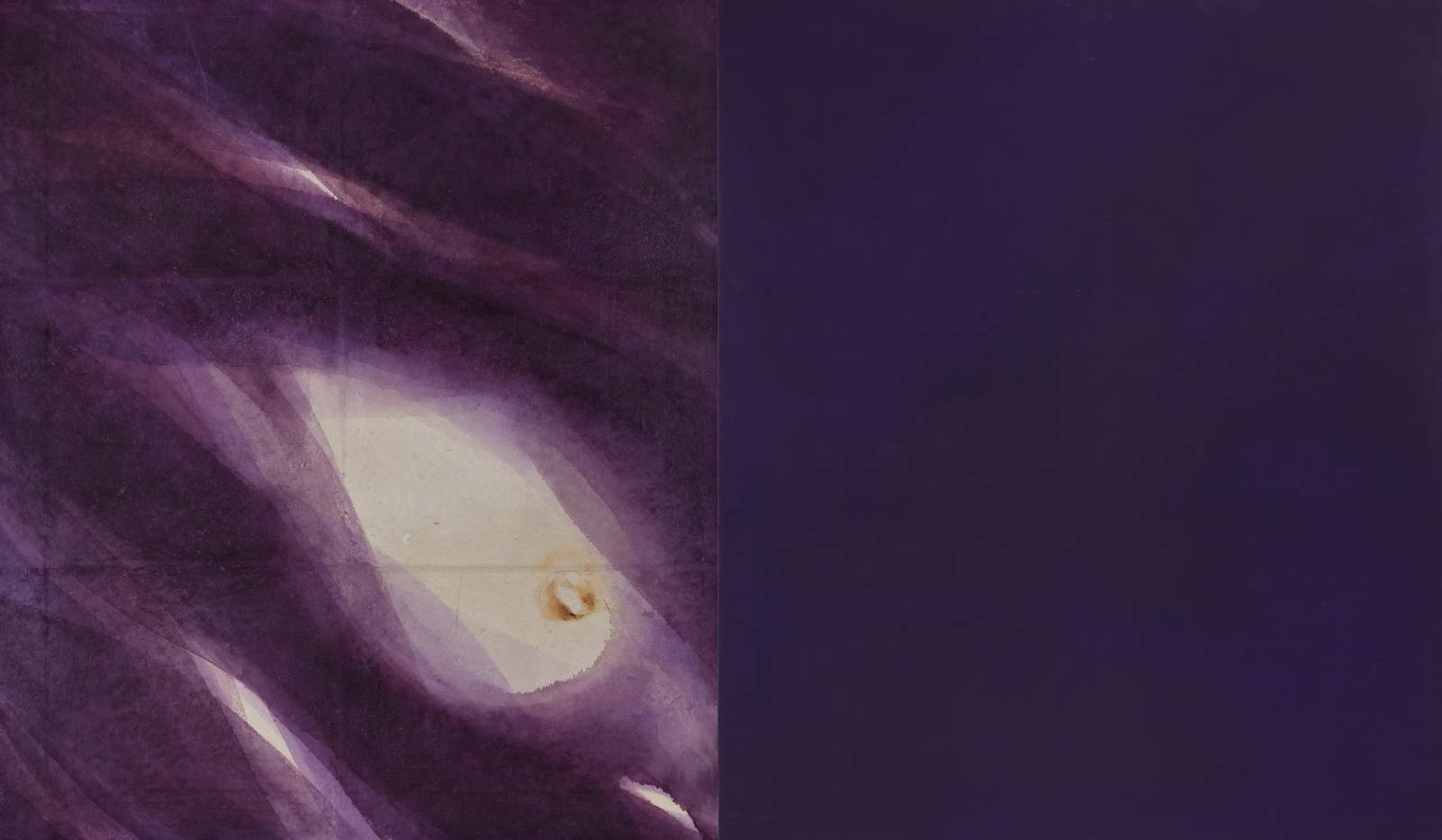

The second painting hanging in the studio is a triptych from the Encantadas series, where a polycentric slope of color flushes in various shades of violet and blue, evoking almost an underwater environment, seem to live thanks to capillary infiltrations of a light that is actually a delicate material outcropping. Such an aesthetic embodies in an exemplary way the meeting of two visual tractions, the Eastern one with its balances of solids and voids, and the Western one with its coloristic wisdom and evocation of a spatiality that goes beyond the plane of the support. The title is an homage to Herman Melville’s short story of the same name, in which the Galápagos Islands are designated by this name, a deceptive archipelago where monstrous creatures live, a fatal apparition in the fog that “questions the gaze on things.”

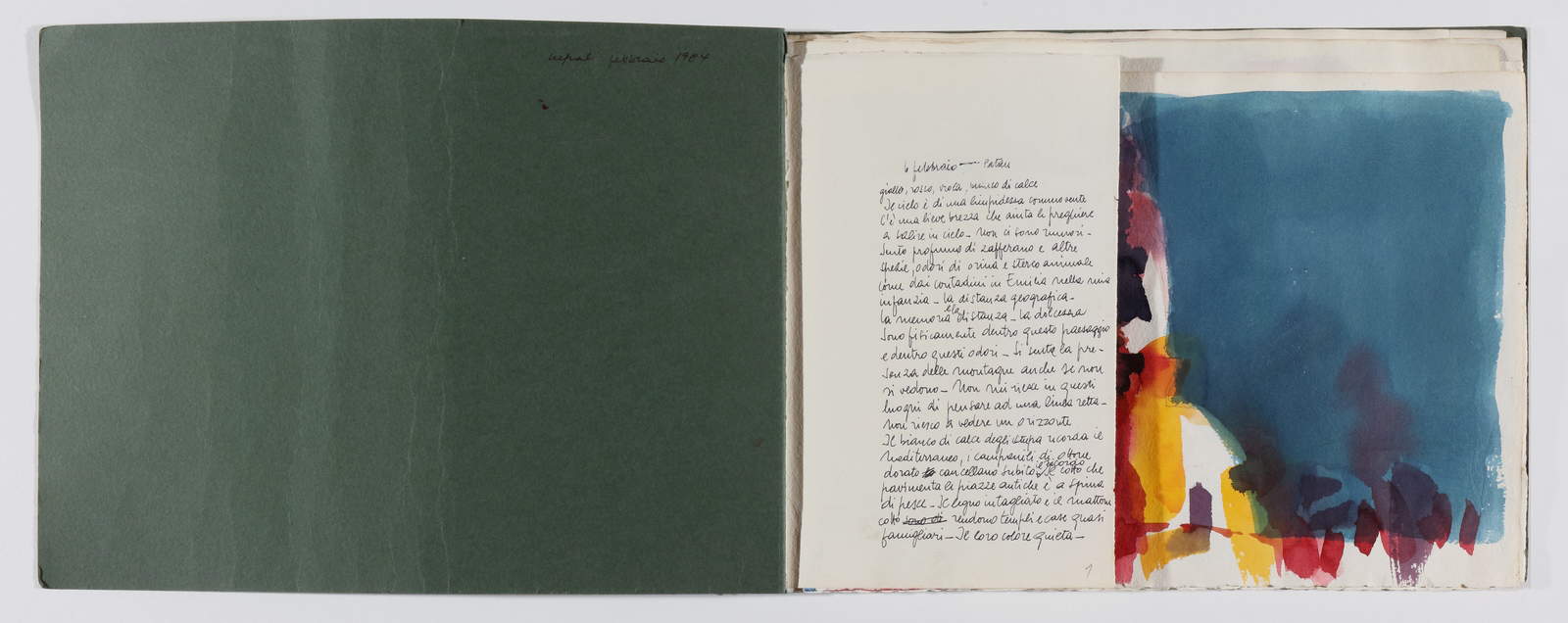

The flawlessness of this result is the outcome of a long process of image processing, starting when a leaf or a color glimpsed by chance resonates in him as sources of forms and signals to be reworked from the ideational point of view, in the first instance through a crowd of small drawings (kept in boxes), sometimes executed automatically and overthinking, which will become the matrices of the idea. The composition is then structured more concretely in a series of watercolors on Fabriano paper of a larger format in which there is already the definition of the work as far as the scanning of spaces, choice of colors and reciprocal positioning of forms.

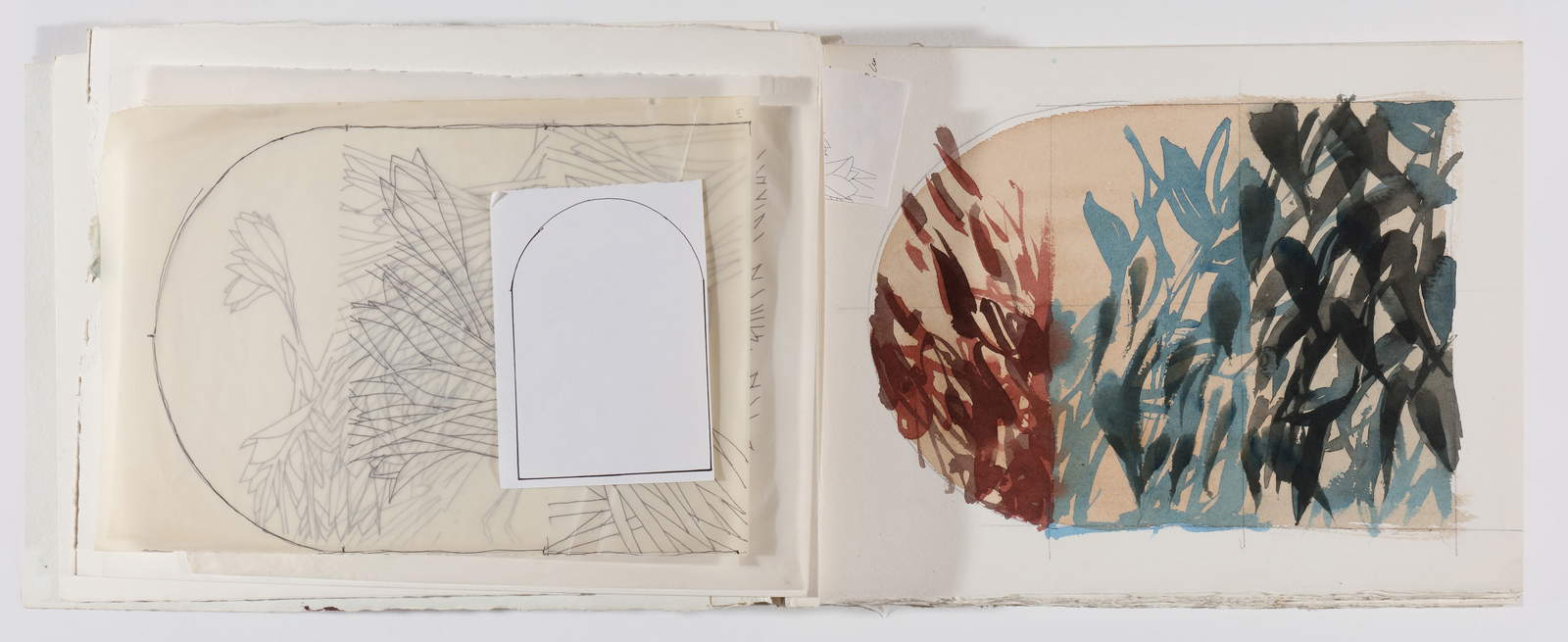

We approach his work table, a wooden plank supported by two easels on which the pictorial actions exceeding the size of the papers have left a harmonious superimposition of traces diluted in time: in fact, each passage of the brush is done horizontally to avoid undesirable drippings and to allow the artist to be physically in full control of the space, which he interprets as a theater of infinite variations of simple but precise gestures derived from the study of calligraphers. We browse through an album of these watercolors made at the design stage, in which the work is fully established in a smaller format, with a more ringing and superficial color tone due to the different composition of the paper. Benati explains that at this stage “the work is done, in his head,” but that before moving on to the canvas where he cannot make mistakes he must memorize the rhythm and intensity of gestures necessary to replicate his mental image exactly.

He lays a white sheet of paper on the table, then dips a broad, flat Chinese brush into a bucket of paint (placed with many others on a shelf behind him). A few synthetic touches, all played on the angle of the brush in relation to the plane and the controlled release of the water with which the bristles are impregnated, bring to the surface on the seemingly muted surface some of the most recurrent forms of his expressive vocabulary, already trembling with moisture, thickening and glazing. Witnessing the appearance of these imaginative ectoplasms, we understand how much in his work even very slight differences in pressure and permanence of color can upset the climate of the image by giving rise to completely different visual habitats, even while using the same forms. “In this game,” he says, "everything is a chase, the concern is always to have an internal balance, rhythms, clarity, sometimes uncertainties. What will eventually happen on canvas is never, therefore, the simple transfer of a predetermined sketch, but a living dialogue with the material that will make something happen that in watercolors on paper is not yet final, bringing it to completion.

Somewhat reluctantly, we prepare to leave this hortus conclusus, where thoughts seem to become sharper as emotions decant mildly into the painting. Before saying goodbye, we linger with our gaze on the threshold of the further rooms concatenated to the entrance corridor (to which we are not admitted) where we glimpse from afar other work tables and many paintings, all leaning against the wall so as to exhibit the back, on which we can read hand-lettered notations inherent to the title and year of creation. Some are wrapped in protective plastic, while others are without it, an indication, we try to imagine, of the artist’s constant relationship with them. Regarding the constitutive synchronicity of his work, Benati tells us, “Every now and then it happens that you forget works made while waiting for something to happen and they seem to have grown old, but when you find them again at a distance of time they appear active again: you look at them again and understand that they are waiting for you. Painting for me is a continuous entering, leaving and returning to the work. Sometimes I look at my paintings and nothing happens, sometimes I hear a sound that alarms me and I wonder: what can happen again? It is a great game that pushes one to believe in moments that are in some ways barbaric.”

We leave, peering with a hint of voyeurism at the shelves of the bookstore, crowded with literary texts and artistic subjects, as well as cards printed as invitations to his numerous exhibitions held over the years, a tangible indication of the consistency of his research, to which maturity has bestowed fullness without leaving signs of fatigue. The invitation, now, is to immerse oneself in his solo exhibition in Reggio Emilia, a precious opportunity offered by the Fondazione Palazzo Magnani to inhabit with the gaze his multiform visual universe by retracing his formation in a truly “enchanted” journey, the result of a research that, with good reason, curator Walter Guadagnini defines as “secluded but among the most significant of Italian art at the turn of the century.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.