Art, together with literature and cinema, has told by bearing witness to one of the most terrible periods in history, one of the greatest tragedies ever of humanity: the horrors of the Holocaust, the persecution suffered by Jews under the racial laws enacted by the Nazi regime, the deportations and concentration and extermination camps, and death in the gas chambers. Unspeakable atrocities carried out in World War II in the name of the idea of the superiority of a single race, the Aryan race, for the final elimination of all Jews and minorities. A dramatic page of History that saw women and men, children and adults suddenly torn from their daily lives, their homes, their habits, their affections, forced to take refuge and hide, often in vain because they were later discovered or denounced by unthinkable and unsuspected spies among neighbors, “friends,” acquaintances, and taken away en masse to places from which in most cases they would never return. Among the deportees there were many people who recounted with their drawings and paintings what it meant to be Jewish at that moment in history: images with which they secretly illustrated what they themselves suffered and saw inside the ghettos and concentration camps and which were found when their authors had already been killed or memories indelible in the minds and eyes of survivors who once liberated found in art a means of expressing the terrible moments they themselves had experienced. In any case, art is to be considered a testimony and a tool to pass on the memory, to make future generations understand how evil humanity is capable of, and from this reflection to ensure that all this hatred never occurs again. May none of what happened with Nazism and racial persecution ever happen again. Therefore, art (and more) serves the purpose of not forgetting.

On the occasion of Remembrance Day we tell you on these pages, as we have been doing for a few years now, the story of a deportee and interne at Auschwitz who, once liberated, and thus saved, depicted in his drawings and paintings the tragedy that he saw and was carried out in the concentration and extermination camp on innocent people. Works that then became testimonies of what he himself had seen and felt.

This is the story of David Olère, born on January 19, 1902, in Warsaw, Poland, where he attended the Academy of Fine Arts. Between 1921 and 1922 he was employed as an assistant architect, painter and sculptor at the Europaïsche Film Allianz. In Berlin he worked with Ernst Lubitsch, a famous film director and producer, and created various set designs. His career thus began as a set designer in the film industry, also working for Paramount Pictures, Fox Films, and Columbia Pictures. Moving to Paris, he married Juliette Ventura in 1930, from whose union his son Alexandre was born. When war was declared in Europe, David was mobilized to the 134th Infantry Regiment at Lons-le-Saunier. On February 20, 1943, he was arrested by French police in the Seine-et-Oise department because of his Jewish origins and interned in the Drancy camp, and on March 2 he was then deported to Auschwitz. In the Auschwitz camp Olère remained for almost two years, from March 2, 1943 to January 19, 1945, and here he worked in the Sonderkommando, a special labor unit forced by the Nazis to remove bodies from gas chambers and remains from crematoria. Selected by the camp authorities from the moment the convoys of deportees arrived, the members of the Sonderkommando lived in special areas, separated from the others to prevent leaks about what was really happening there; they are what Primo Levi in The Drowned and the Saved calls “wretched laborers of the massacre,” and on whose role the accusation has fallen, whether shared or not, that they did not refuse, that they did not try to do anything to prevent the killing of so many innocents. David Olère did not refuse, probably could not refuse; he was one of the few deportees to see with his own eyes all stages of the extermination process coming out alive, even though most of the time he was employed making artwork for the SS and translating radio broadcasts since he knew many languages.

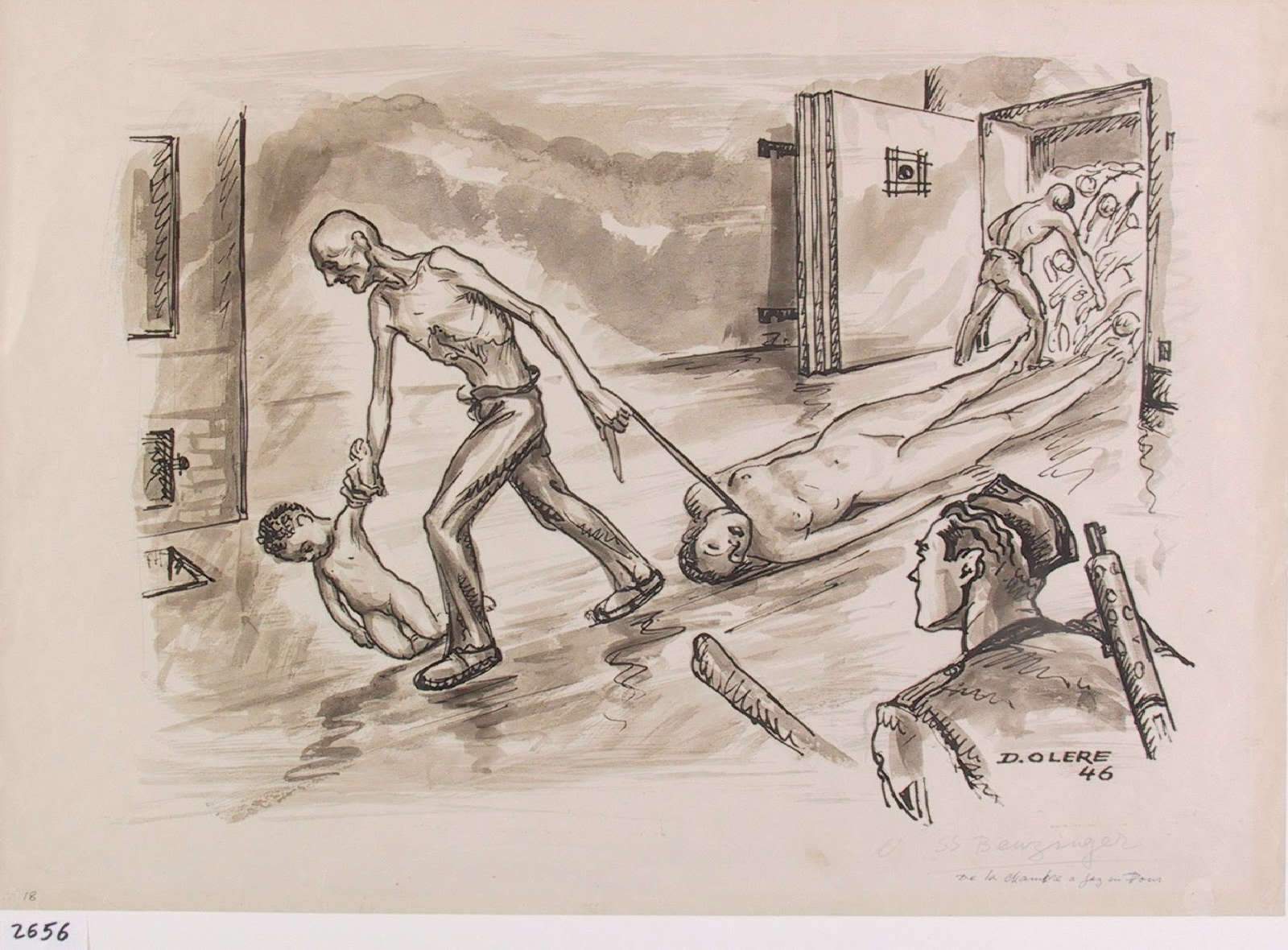

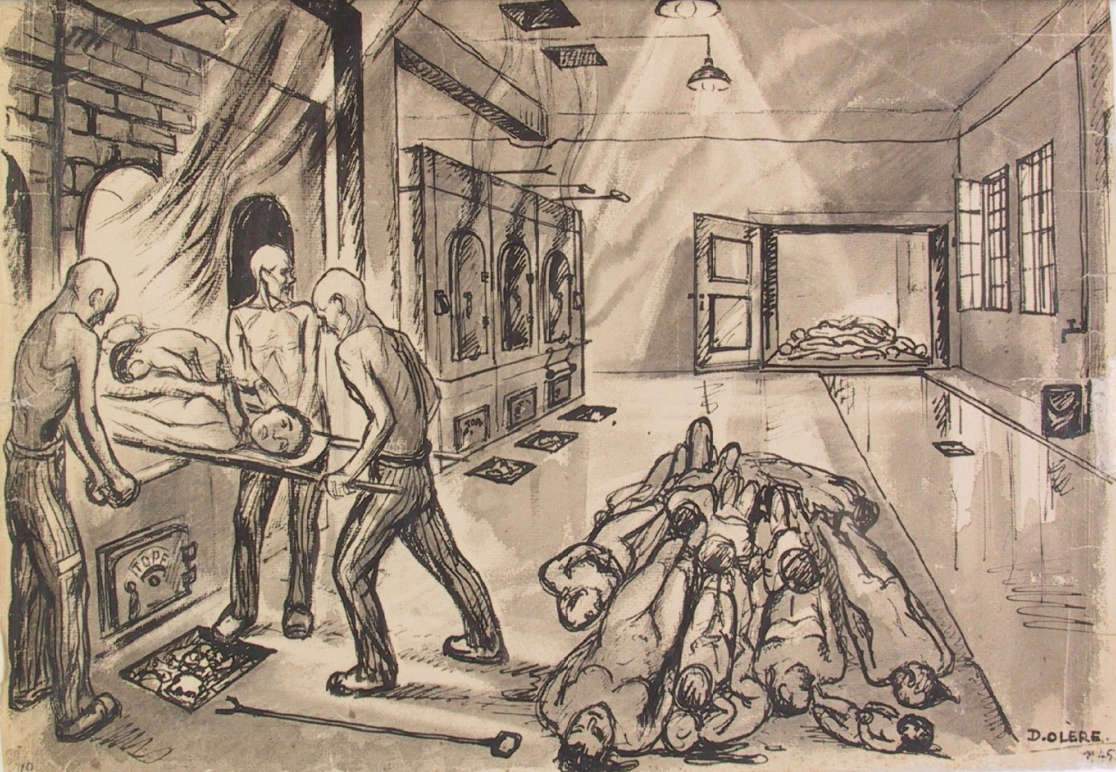

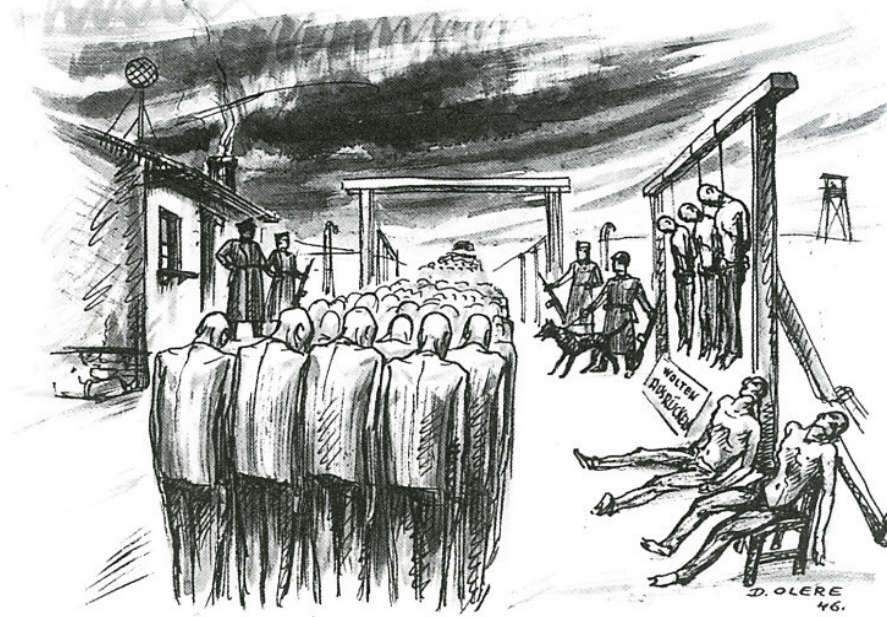

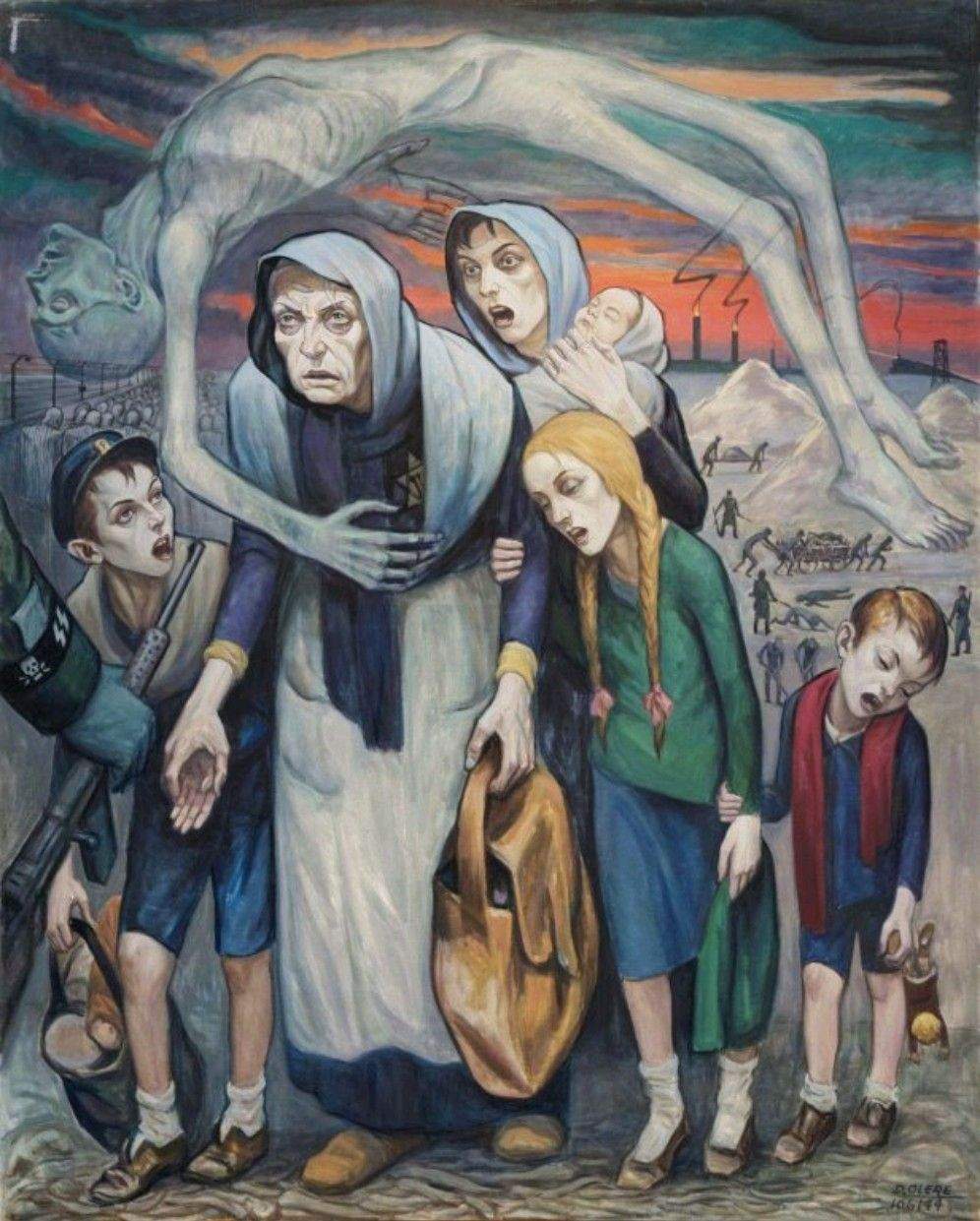

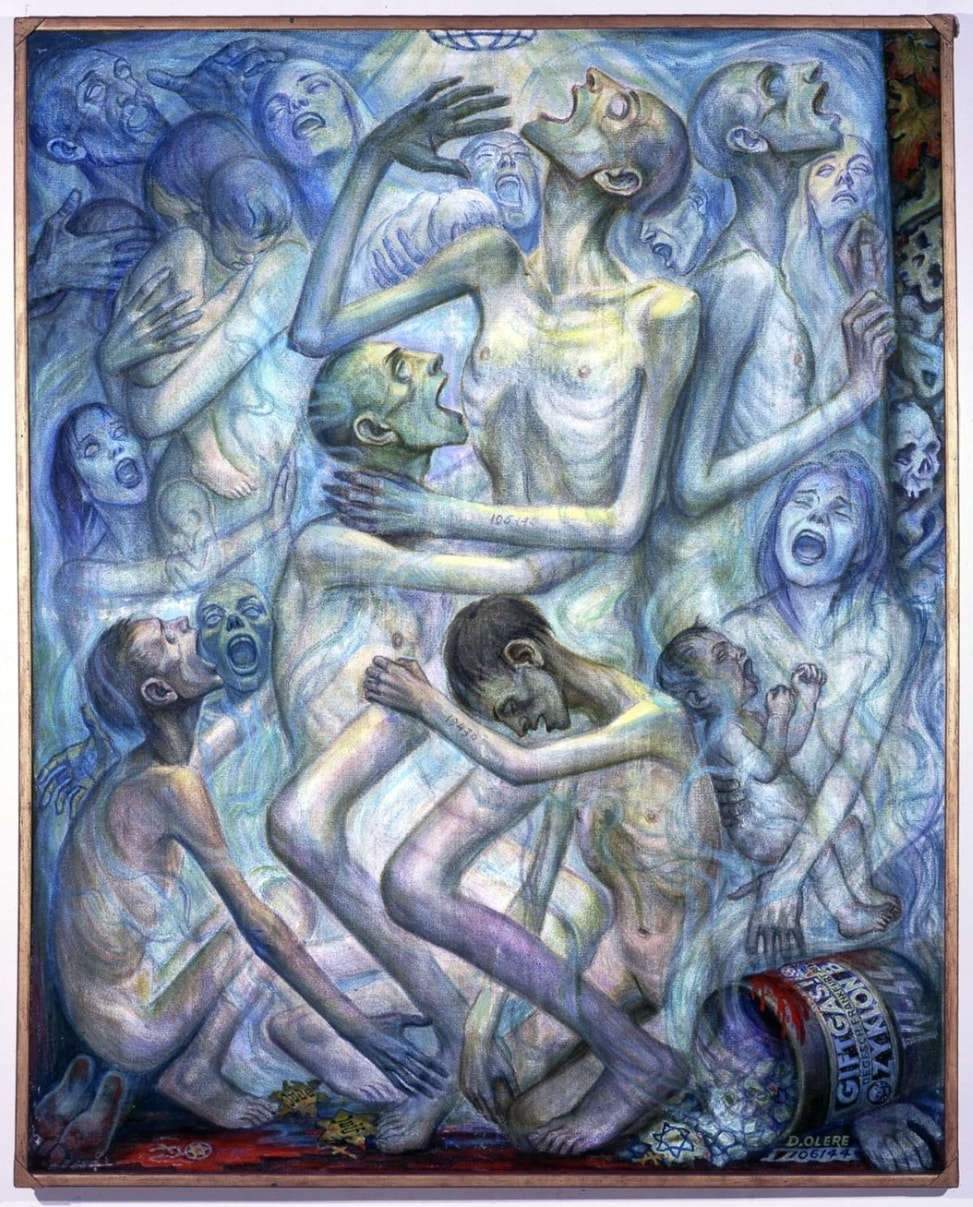

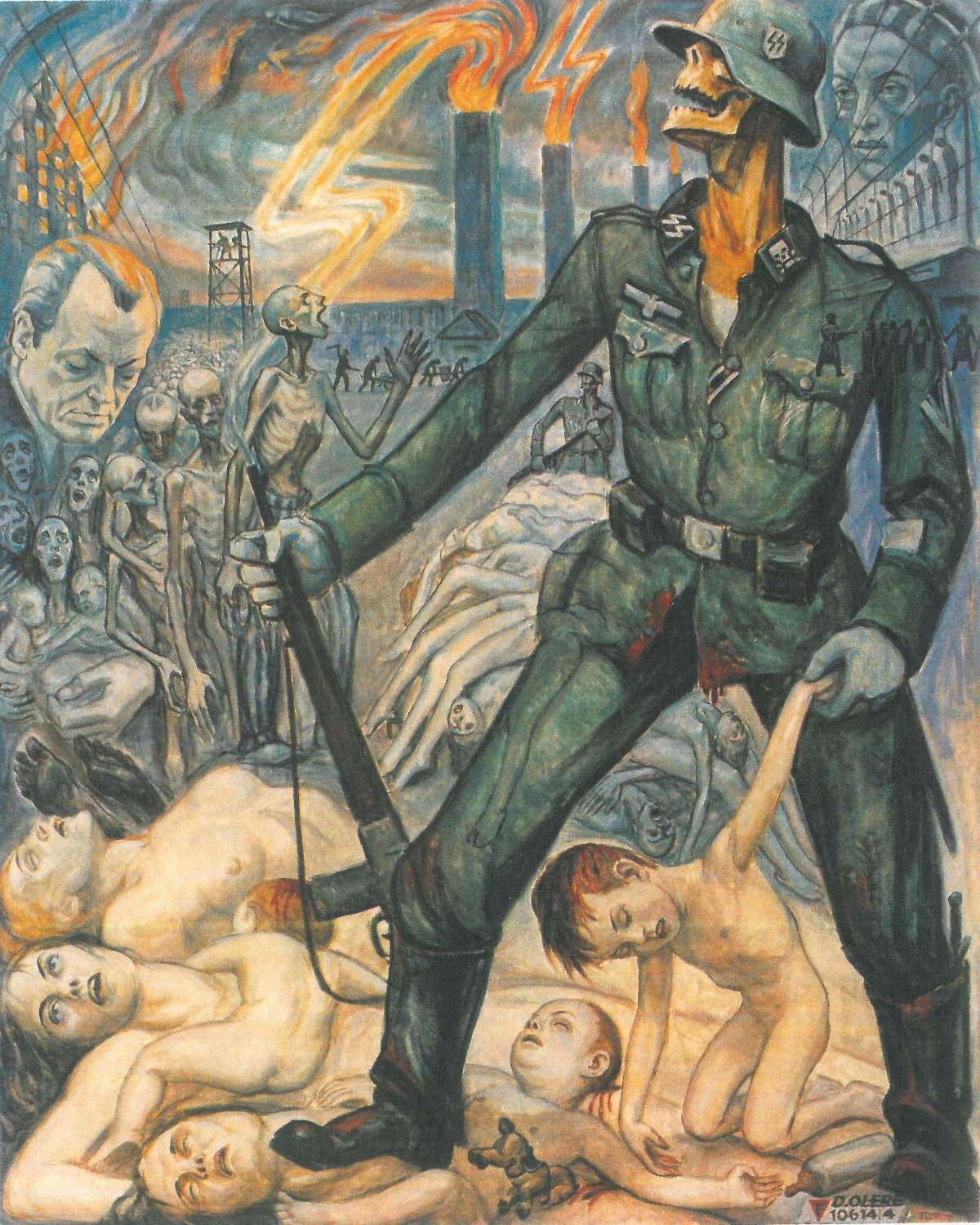

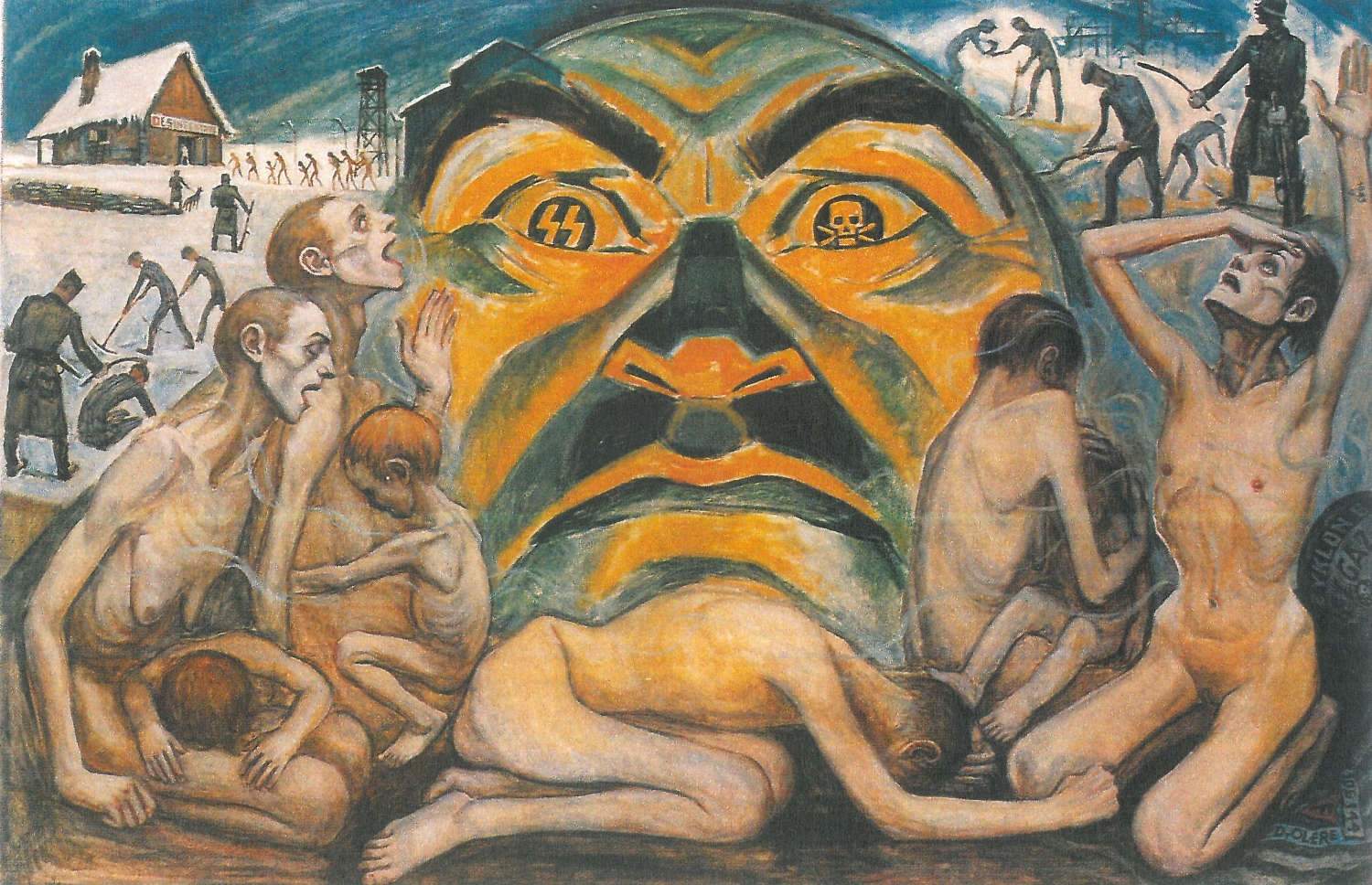

All the horror that had been etched in his eyes transformed him with his works into testimony once he was liberated by the Americans at Ebensee in May 1945, where he was after being forced to take part in the death march in the evacuation of the Auschwitz camp in January of that year (from Auschwitz he arrived first at Mauthausen and then at Ebensee). The works that Olère created after the Liberation should be seen as a gesture that he felt compelled to make to those who had not survived, to denounce Nazi crimes, to honor the victims of the Holocaust, and not to forget what had happened inside the Auschwitz camp. His drawings and paintings recount that horrible reality, give an account of what was happening in the camp, in the gas chambers and in the crematoria. He was the first to draw plans and sections of these environments to explain exactly how the Nazis ran their factories of death. Sometimes, in his paintings he depicts himself as a ghostly face, as a silent witness observing terrible and inhumane scenes that would forever live on in his memory.

“In his works, David Olère combines artistic vision with carefully reconstructed camp realities. As a result, his paintings depict those who did not survive, sometimes as faces and ghosts of witnesses presented in the pictorial scenario, sometimes forming the main theme of the work,” explains Agnieszka Sieradzka, art historian of the Auschwitz Memorial Collections. "Olère also condemns the perpetrators of those events, who also occupy considerable space in his works. These works also contain autobiographical motifs. The artist showed what kept him alive and ultimately helped him survive: his love for his wife, his knowledge of languages, his ability to acquire additional portions of food.

David Olère, Departure for Work (1946; drawing, 43 x 33 cm; Lohamei HaGeta’ot, Ghetto Fighters House)

Often in the paintings we see the author himself, with a number tattooed on his arm, as a prisoner of the Auschwitz camp, who saw the extermination process with his own eyes.“ In his works, Sieradzka adds, ”we can see the stages of the extermination process: people in the locker room, in the gas chamber, scenes in which the victims’ gold teeth were pulled out, scenes of the crematorium and the burial of the bodies. In Olère’s works we can also see cruel medical experiments, torture and killing of prisoners by the SS, hunger, fear and despair that were part of the daily life of the prisoners." For scholars, Olère’s works are uniquely valuable as documents illustrating the atrocities of extermination; they are depictions of details that only members of the Sonderkommando were aware of.

Among his best-known paintings is The Food of the Dead for the Living, in which Olère himself is depicted in the foreground, his face hollowed out and his eyes wide, picking up food abandoned near the locker rooms of the crematorium to throw over the fence to the inmates of the women’s camp. But also other scenes depicting the arrival of a convoy with a wagon in the foreground carrying the corpses of an earlier convoy, or three Muselmänner (a term used to refer to those who were destined for death due to their physical and mental exhaustion) supporting each other as they stagger toward the gas chamber. Or those who could not work, the reason often for immediate death sentences, or the moment of administering a medical experiment injection. Among the most tragic images is the Gassing.

The largest collection of David Olère’s paintings is preserved in the collections of the Auschwitz Memorial (also present is a portrait of Olère thanks to writer, historian and lawyer Serge Klarsfeld). In fact, the latter donated in 2014 to the Auschwitz Memorial the first ever work by the artist to enter the museum’s collections: it is a self-portrait in close-up with the typical striped “uniform” with cap and sewn on his chest the number 106 144 that marked him inside the camp. Other drawings, such as the one depicting Olère himself being punished in the bunker, are part of the collections of Yad Vashem, the International Holocaust Memorial Center; others are kept at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York, still others at the Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum in Galilee, a few others belong to private individuals.

David Olère died in Noisy-le-Grand, France, in August 1985. After his passing, his wife and son Alexandre, as well as heirs such as his grandson, continued the artist’s will: his paintings and drawings were exhibited in various museums to spread the message of his works, to tell the reality of Auschwitz and honor the victims of the Holocaust. Strong, often shocking images that shout the will not to forget.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.