When one’s thoughts dwell on the figure of the mermaid, a unique depiction comes to life: bewitching, long hair and a tail that takes the shape of different fish. The mermaid has been part of the artistic imagination for millennia, and hers is among the oldest and best-known mythological figures. In the Greek folk beliefs of the 7th-5th centuries B.C., the representation of the mermaid was different from what it is today. She was half woman and half bird and through her song led the unfortunate to death. In theOdyssey, one of the earliest works to include the image of the creature, Odysseus decides to plug his companions’ ears by having himself tied to the ship’s mast in order to listen to its melodies without being fooled. The episode is depicted in the Vase of the Sirens, a red-figure stamnos from the fifth century B.C. (Greek Archaic age), painted by the Siren Painter and preserved in the British Museum in London. Although to this day there is no certainty about the etymology of the Sirens’ name, it would seem that there is a connection with the Semitic root “sir,” meaning “song.” Other scholars have recalled the Greek word “seiráo,” meaning “I enchain,” from which “siren” would be derived as “she who enchains, who binds, who binds.” It is certainly not strange for the Greeks to depict a woman in the guise of a bird of prey: think of the Furies (or Furies), personifications of female vengeance, the Harpies and the Lamias, women-rapists from whom witches are derived. Indeed, the figures seem to derive from a single strain: a femininity of doom and death, daughter of Hecate, deity of witchcraft. With the advent of the Middle Ages, the followers of Hecate were later associated with Lilith, the first woman.

The siren therefore in antiquity already had a negative connotation; she was not a woman, but a fatal female creature. As time went on, her negative symbolism was assimilated by medieval religious culture, which modified her features. In that historical context, already rich in associations between the feminine and the demonic, the mermaid achieved the title of fatal woman. The medieval woman, capable of enchantment and deception through beauty was considered a devourer of men similar to the sea mermaid, a creature half fish that hid in the mysterious depths where neither the human eye nor reason could reach. In fact, even with the advent of Christianity, an ideology related to pagan creatures and deities of the night persisted.

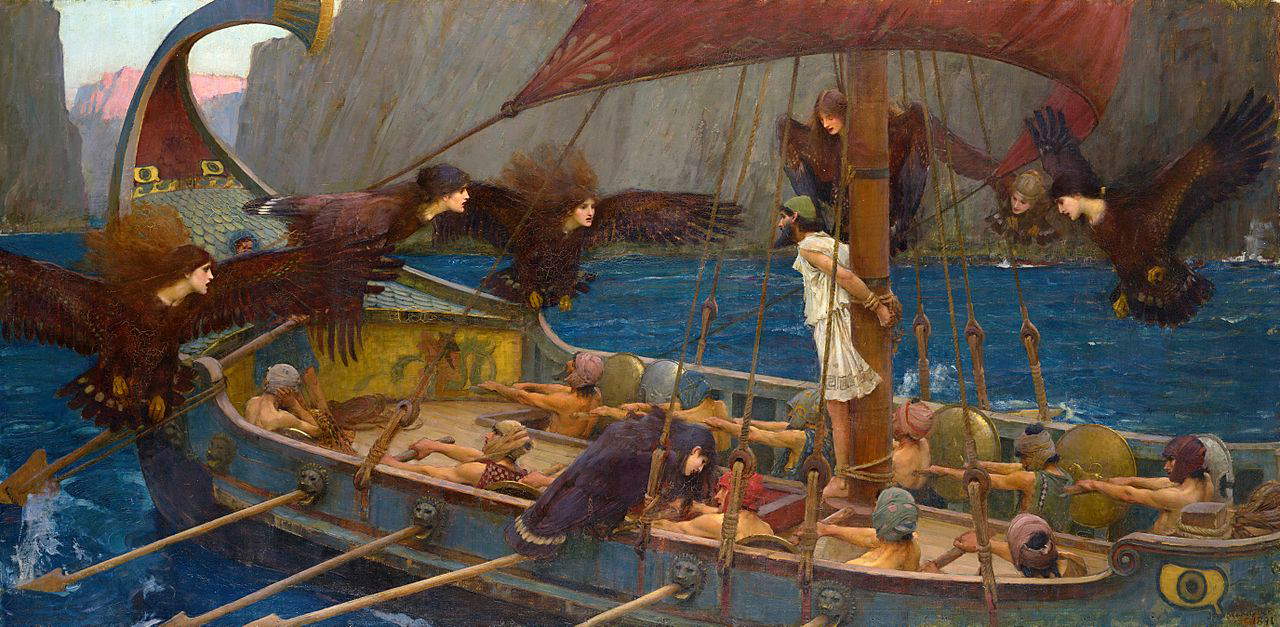

“Sirens are sea maidens who deceive sailors by their beautiful appearance and alluring them with song; and from the head and down to the navel they have the body of a maiden and are in every way like the human species; but they have scaly fish tails which they always conceal in the whirlpools.” so we read in the Liber monstrorum de diversisgeneribus, an 8th-century text meant to clarify how true or false the definitions about monsters of the time might be. Depicted in these new guises, the mermaid can be found in medieval miniatures and capitals, often in bicaudate form, with her double tail spread symmetrically apart. One example is the marble sculpture of the bicaudate Siren, dating from around 1100-1149, now housed in the Museo Lapidario del Duomo in Modena. Another representation, however, is found in the miniature on parchment from the 13th-century Bestiary of Hugh of Fouilloy, depicting a Siren and the Onocentaur. Those captivated by the mermaid figure, however, are not only sailors. From the late nineteenth century, the Romantic era of sentiment, the majesty of nature and the sublime, until the early twentieth century, the mermaid returned to be depicted with a new erotic charge by English and French artists. The long hair and long tails thus became entrenched in the collective imagination. Léon Belly is among the first to rediscover her with his Ulysses and the Sirens of 1867. The German Wilhelm Kray was so fascinated by it that he dedicated several paintings to it, all painted in semi-darkness: The Sailor and the Sirens, Sleeping Fisherman with Sirens of 1869, The Sirens of 1874, and The Song of the Sirens. In 1891, John William Waterhouse painted his Ulysses and the S irens in which he took up the idea of the woman-daughter. In 1900, the same artist conceived A Mermaid, which features the creature intent on combing her hair. Herbert James Draper immortalized her in an Ulysses and the Sirens in 1909, giving her an irresistible charm.

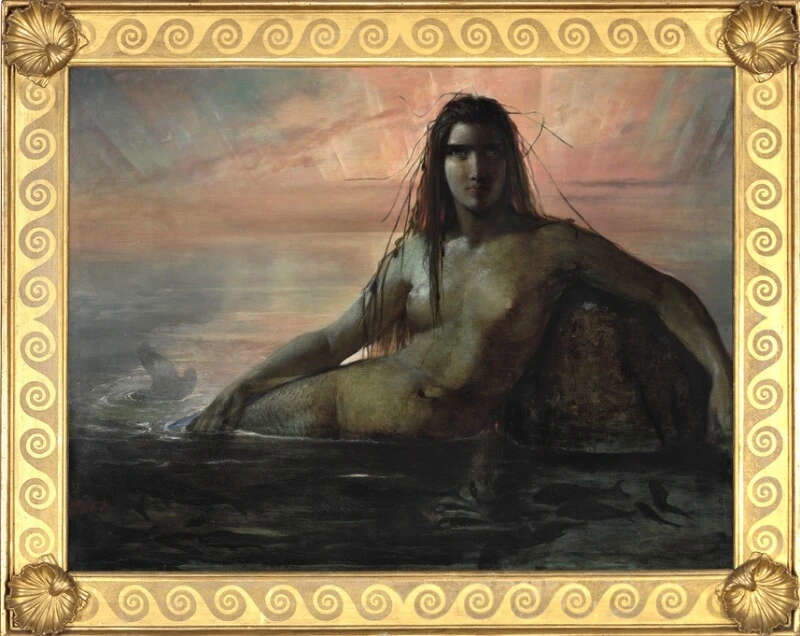

In a world dominated by male art, Polish naturalized Danish artist Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann (Warsaw, 1819 - Copenhagen, 1881) knew from the beginning that she had to compete with her male colleagues in a male-dominated profession. Although there were expectations regarding the motifs women should paint, based on their sensitive and feminine nature, Jerichau-Baumann never allowed herself to be limited by the conventions of her time. In the Danish Golden Age, which developed between 1800 and 1850, as opposed to prevailing themes such as Romantic landscape painting, Jerichau-Baumann pursued a broad repertoire of subjects with a focus on female figures.

In the early part of the 19th century, the mermaid was primarily a literary motif based on Norse legends, and gradually the creature also found its way into popular literature and Copenhagen newspaper periodicals in the 1860s, thanks in part to the 1837 classic The Little Mermaid (Den lille Havfrue in the original language) by Hans Christian Andersen, a friend of Jerichau-Baumann. The artist understood the appeal of mermaids from that period to the point of interpreting and translating it into new visual imagery. The thematization of the sea creature thus found a place in the artistic community, characterizing Jerichau-Baumann’s production from 1850 to 1870. The mermaid was the figure par excellence, and Jerichau-Baumann not only painted her but charged her with the same eroticism used by artists such as Gustav Wertheimer and Knut Ekwall. His depiction of mermaids was not limited to simple aesthetics, but explored the depth and fascination that this mythological figure held for the audiences of his time. Over the years, Jerichau-Baumann experimented with two related types of mermaids, each with different faces, hair colors and intensity of gaze, often depicted in a waiting pose near the surface of the sea. Her mermaids are featured in three main copies. The first, titled A Mermaid(Havfrue in Danish), dates from 1861, when it was exhibited at the Paris Salon, attracting the attention of a French art critic. The second version was completed in 1862 and exhibited at the London World’s Fair. The third version of A Mermaid, dated 1873, was exhibited in Vienna and is probably the most famous of the three.

In the case of Jerichau-Baumann’s Mermaids, his creatures appear seductive as they lie rocking near the surface of the sea, hiding the reef that could run ships aground. In the 1861 and 1873 paintings, in fact, the creatures appear as two dark-haired seductresses, with seaweed in their hair and a fixed gaze toward the viewer, not allowing him to escape. Not far away, their tails can be glimpsed as small fish swim around them. What’s more, the artist’s mermaids are characterized by an aura reminiscent ofOrientalism, an art movement that originated in the late 18th century and developed later in the 19th century. Indeed, the writer Andersen, a friend of Jerichau-Baumann, may have appreciated her ability to visually translate the Orientalist elements of his Little Mermaid as the castle described in his fairy tale. To date, two of Jerichau-Baumann’s three mermaid paintings are in Danish museum collections. The 1861 version is kept at Brandts in Odense, while the 1873 version is on display at the New Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen. The figure of the mermaid, therefore, presents a complex interpretation as it combines seemingly contradictory elements: on the one hand, she has the finned tail of a fish, an attribute that connects her to the world of the deep sea, the unconscious and her mysterious and unexplainable nature; on the other hand, she possesses feminine attributes and a human psyche, suggesting a human-like form of intelligence, emotions and desires. The creature, therefore, is not simply an animal being or a common mythological creature, but embodies a deep enigmatic duality.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.